Posts

Article of the week: Use of 68Ga-PSMA/PET for detecting lymph node metastases in primary and recurrent PCa and location of recurrence after radical prostatectomy: an overview of the current literature

Every week, the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Week from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

If you only have time to read one article this week, we recommend this one.

Use of gallium‐68 prostate‐specific membrane antigen positron‐emission tomography for detecting lymph node metastases in primary and recurrent prostate cancer and location of recurrence after radical prostatectomy: an overview of the current literature

Henk B. Luiting*, Pim J. van Leeuwen†, Martijn B. Busstra*, Tessa Brabander‡, Henk G. van der Poel†, Maarten L. Donswijk§, André N. Vis¶, Louise Emmett**††, Phillip D. Stricker‡‡§§¶¶ and Monique J. Roobol*

*Department of Urology, Erasmus University Medical Centre, Rotterdam, †Department of Urology, Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam, ‡Department of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine, Erasmus University Medical Centre, Rotterdam, §Department of Nuclear Medicine, Netherlands Cancer Institute, ¶Department of Urology, Amsterdam UMC, Location VUmc, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, **Department of Nuclear Medicine, St Vincent’s Hospital, ††University of New South Wales, Sydney, ‡‡St. Vincent’s Prostate Cancer Centre, §§Garvan Institute of Medical Research, Kinghorn Cancer Centre, Darlinghurst and ¶¶St Vincent’s Clinical School, UNSW, Sydney, NSW, Australia

Abstract

Objectives

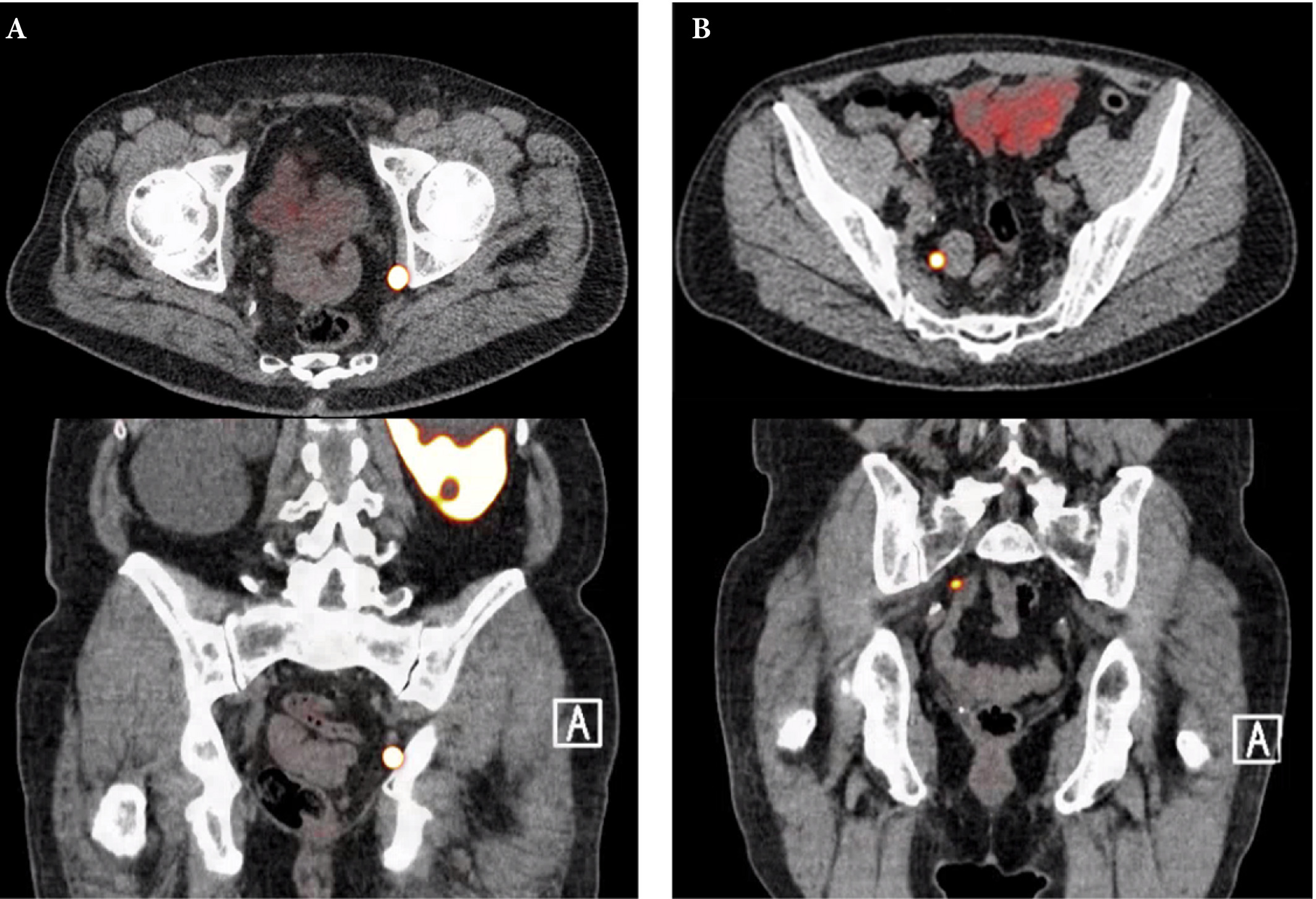

To review the literature to determine the sensitivity and specificity of gallium‐68 prostate‐specific membrane antigen (68Ga‐PSMA) positron‐emission tomography (PET) for detecting pelvic lymph node metastases in patients with primary prostate cancer (PCa), and the positive predictive value in patients with biochemical recurrence (BCR) after initial curative treatment, and, in addition, to determine the detection rate and management impact of 68Ga‐PSMA PET in patients with BCR after radical prostatectomy (RP).

Materials and Methods

We performed a comprehensive literature search. Search terms used in MEDLINE, EMBASE and Science Direct were ‘(PSMA, 68Ga‐PSMA, 68Gallium‐PSMA, Ga‐68‐PSMA or prostate‐specific membrane antigen)’ and ‘(histology, lymph node, staging, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, recurrence, recurrent or detection)’. Relevant abstracts were reviewed and full‐text articles obtained where possible. References to and from obtained articles were searched to identify further relevant articles.

Results

Nine retrospective and two prospective studies described the sensitivity and specificity of 68Ga‐PSMA PET for detecting pelvic lymph node metastases before initial treatment, which ranged from 33.3% to 100% and 80% to 100%, respectively. In eight retrospective studies, the positive predictive value of 68Ga‐PSMA PET in patients with BCR before salvage lymph node dissection ranged from 70% to 100%. The detection rate of 68Ga‐PSMA PET in patients with BCR after RP in the PSA subgroups <0.2 ng/mL, 0.2–0.49 ng/mL and 0.5 to <1.0 ng/mL ranged from 11.3% to 50.0%, 20.0% to 72.7% and 25.0% to 87.5%, respectively.

Conclusion

The review results showed that 68Ga‐PSMA PET had a high specificity for the detection of pelvic lymph node metastases in primary PCa. Furthermore, 68Ga‐PSMA PET had a very high positive predictive value in detecting lymph node metastases in patients with BCR. By contrast, sensitivity was only moderate; therefore, based on the currently available literature, 68Ga‐PSMA PET cannot yet replace pelvic lymph node dissection to exclude lymph node metastases. In the salvage phase, 68Ga‐PSMA PET had both a high detection rate and impact on radiotherapy planning in early BCR after RP.

Article of the month: Understanding volume–outcome relationships in nephrectomy and cystectomy for cancer: evidence from the UK Getting it Right First Time programme

Every month, the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Month from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to the article itself, there is an editorial written by a prominent member of the urological community and a video prepared by the authors; we invite you to use the comment tools at the bottom of each post to join the conversation.

If you only have time to read one article this month, we recommend this one.

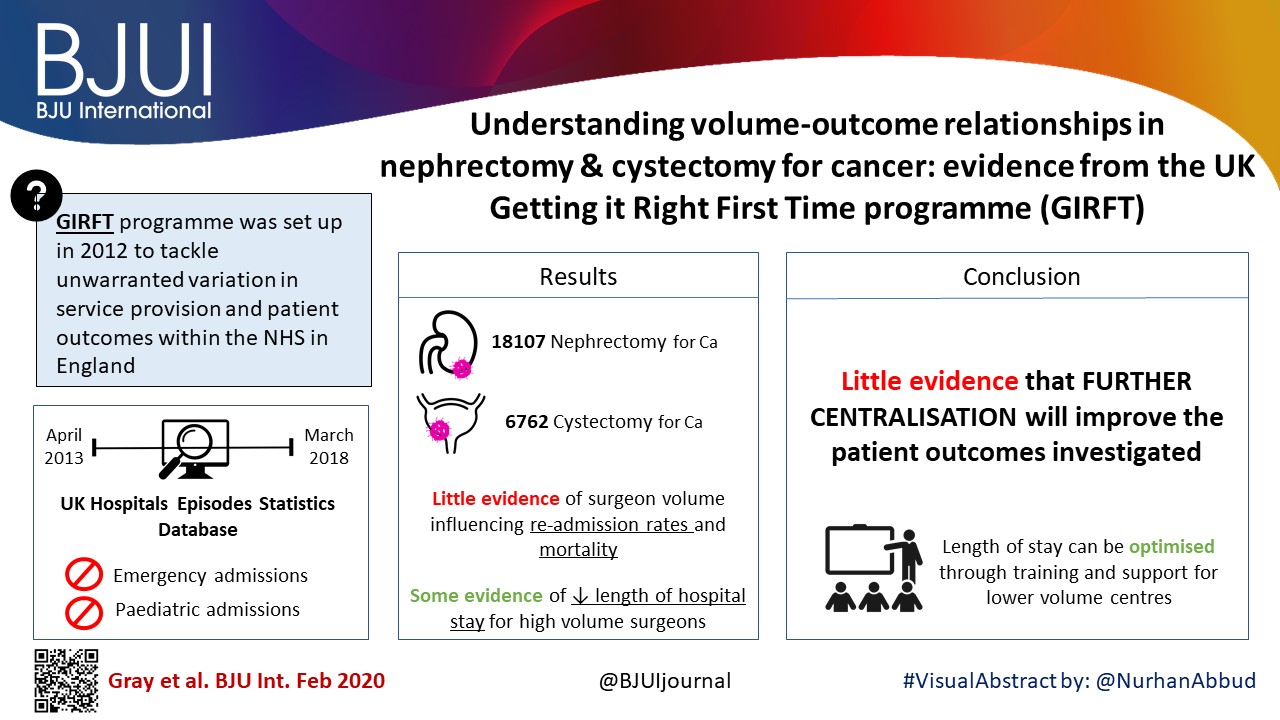

Understanding volume–outcome relationships in nephrectomy and cystectomy for cancer: evidence from the UK Getting it Right First Time programme

William K. Gray*, Jamie Day*, Tim W. R. Briggs* and Simon Harrison*†

*Getting it Right First Time Programme, NHS England and NHS Improvement, London, UK and †Pinderfields Hospital, Mid Yorkshire Hospitals NHS Trust, Wakefield, UK

Abstract

Objectives

To investigate volume–outcome relationships in nephrectomy and cystectomy for cancer.

Materials and Methods

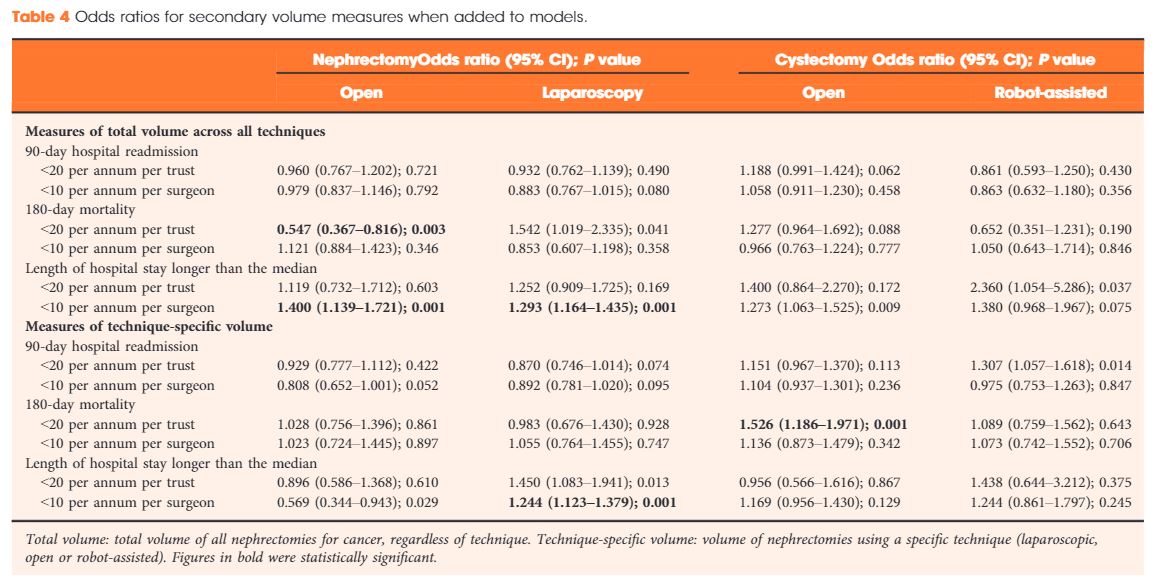

Data were extracted from the UK Hospital Episodes Statistics database, which records data on all National Health Service (NHS) hospital admissions in England. Data were included for a 5‐year period (April 2013–March 2018 inclusive) and data on emergency and paediatric admissions were excluded. Data were extracted on the NHS trust and surgeon undertaking the procedure, the surgical technique used (open, laparoscopic or robot‐assisted) and length of hospital stay during the procedure. This dataset was supplemented by data on mortality from the UK Office for National Statistics. A number of volume thresholds and volume measures were investigated. Multilevel modelling was used to adjust for hierarchy and confounding factors.

Results

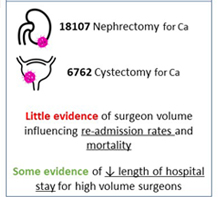

Data were available for 18 107 nephrectomy and 6762 cystectomy procedures for cancer. There was little evidence of trust or surgeon volume influencing readmission rates or mortality. There was some evidence of shorter length of hospital stay for high‐volume surgeons, although the volume measure and threshold used were important.

Conclusions

We found little evidence that further centralization of nephrectomy or cystectomy for cancer surgery will improve the patient outcomes investigated. It may be that length of stay can be optimized though training and support for lower‐volume centres, rather than further centralization.

Editorial: All for one, one for all: is centralisation the way to go?

The need to centralise complex surgical procedures in large centres remains at the core of many health policy discussions. Much of the debate is focussed on three main aspects: (i) outcomes, (ii) costs and (iii) accessibility. Gray et al. [1] recently noted that increasing centralisation may be unnecessary for invasive procedures such as nephrectomy and cystectomy. Specifically, they noted almost no difference in outcomes of high‐volume centralised centres and those with lower throughput. Their findings go against most of the current literature on the volume–outcomes relationship, which generally reports a correlation between a hospital’s volume of procedures and improved healthcare outcomes. One could ask what factors specific to their analysis could explain the different observations. For one, the healthcare system in the UK may (and likely) operate in ways different from other European and USA‐based healthcare systems, from which most of the current data are derived. Healthcare in the UK may already be organised in such a way that further centralisation may not improve outcomes, which the authors allude to in their conclusions. Differences in methodology may explain their findings, e.g. their use of multilevel modelling, testing specific incremental volume cutoffs, etc. Outcome selection may play a role as well; length of stay and re‐admissions may vary more according to organisational factors rather than individual surgeon expertise.

Regardless of their findings, we would argue that there are other tangible benefits to centralisation, which extend well beyond ‘better outcomes’. For instance, the management of the modern oncological, and urological, patient is critically dependent on a multidisciplinary team. The inherent multidisciplinary nature of large centres facilitates patients receiving their entire course of treatment at the same place. This enhances the continuity and efficiency of care, both of which are undoubtedly hampered in small peripheral centres that ultimately depend on referrals to larger facilities for advanced care for the most complex patients.

This ties into yet another major advantage of centralised centres, which is the ease of access to research. For instance, our affiliated cancer centre runs >1100 active clinical trials, 42 of which pertain to advanced urological diseases. Such trials provide access to otherwise unavailable therapies and enhance the production, diffusion, and application of knowledge.

In touting the many benefits of centralisation, one would imagine it comes at a significant cost. While this may have been true in the past, recent data comparing the higher‐volume teaching hospitals to lower‐volume non‐teaching centres suggest that centralisation actually decreases the 30‐day hospital costs and have similar costs at 90 days compared with non‐teaching hospitals [2]. Similar trends were also seen with radical cystectomies [3] and prostatectomies [4], showing that with the major urological procedures, centralisation is cost‐effective with at least the same outcomes as compared to peripheral centres.

A common objection to centralisation is that it forces many patients to travel long distances and that this in turn could introduce or worsen discrepancies in accessibility to care. If true, this would have profound social and economic consequences for disadvantaged groups, as well as particularly fragile patients. Many centralised centres have developed approaches to ease the burdens of travelling from afar and, if patients can make the journey, the data suggest a survival advantage over those who are treated at peripheral centres. To this end, Vetterlein et al. [5] stratified >700 000 patients by risk class and demonstrated an overall survival benefit in those with all stages of prostate cancer. In the not‐too‐distant future, patient follow‐up can be shifted almost entirely to telemedicine, which can further alleviate travel burdens.

Our aim is not to promote a system of oncological care based solely at centralised hubs. However, to suggest that all care should be distributed equally across all centres seems unrealistic and may have devastating consequences, particularly for those with advanced disease. We strongly advocate the treatment of complex disease at high‐volume, centralised centres and suggest better use of an impartial classification of what constitutes a ‘complex’ disease. Therefore, one answer to this problem is broadly represented by the redistribution of the different surgical procedures amongst the hospitals.

by Daniele Modonutti, Venkat M. Ramakrishnan and Quoc‐Dien Trinh

References

- , , , . Understanding volume‐outcome relationships in nephrectomy and cystectomy for cancer: evidence from the UK Getting it Right First Time programme. BJU Int 2020; 125: 234– 43

- , , , , , . Comparison of costs of care for medicare patients hospitalized in teaching and nonteaching hospitals. JAMA Netw Open 2019; 2: e195229

- , , et al. Impact of surgeon volume on the morbidity and costs of radical cystectomy in the USA: a contemporary population‐based analysis. BJU Int 2015; 115: 713– 21

- , , et al. Redefining and contextualizing the hospital volume‐outcome relationship for robot‐assisted radical prostatectomy: implications for centralization of care. J Urol 2017; 198: 92– 9

- , , et al. Impact of travel distance to the treatment facility on overall mortality in US patients with prostate cancer. Cancer 2017; 123: 3241– 52

Video: Understanding volume–outcome relationships in nephrectomy and cystectomy for cancer: evidence from the UK Getting it Right First Time programme

Understanding volume–outcome relationships in nephrectomy and cystectomy for cancer: evidence from the UK Getting it Right First Time programme

Abstract

Objectives

To investigate volume–outcome relationships in nephrectomy and cystectomy for cancer.

Materials and Methods

Data were extracted from the UK Hospital Episodes Statistics database, which records data on all National Health Service (NHS) hospital admissions in the England. Data were included for a 5‐year period (April 2013–March 2018 inclusive) and data on emergency and paediatric admissions were excluded. Data were extracted on the NHS trust and surgeon undertaking the procedure, the surgical technique used (open, laparoscopic or robot‐assisted) and length of hospital stay during the procedure. This dataset was supplemented by data on mortality from the UK Office for National Statistics. A number of volume thresholds and volume measures were investigated. Multilevel modelling was used to adjust for hierarchy and confounding factors.

Results

Data were available for 18 107 nephrectomy and 6762 cystectomy procedures for cancer. There was little evidence of trust or surgeon volume influencing readmission rates or mortality. There was some evidence of shorter length of hospital stay for high‐volume surgeons, although the volume measure and threshold used were important.

Conclusions

We found little evidence that further centralization of nephrectomy or cystectomy for cancer surgery will improve the patient outcomes investigated. It may be that length of stay can be optimized though training and support for lower‐volume centres, rather than further centralization.

February 2020 – about the cover

One of the authors of February’s Article of the Month (Understanding volume–outcome relationships in nephrectomy and cystectomy for cancer: evidence from the UK Getting it Right First Time programme) is from Wakefield in Yorkshire, UK.

The cover image shows the moat and ruins of Sandal Castle, which is located in Sandal Magna on the outskirts of Wakefield. The castle was originally built of timber by the 2nd Earl of Surrey, William Warenne, early in the 12th century. In the 13th century, the timber motte-and-bailey castle was rebuilt in stone by a later member of the Warenne family. The castle was maintained until the late 14oos, with the Battle of Wakefield taking place nearby, and a brief resurgence whilst in Royalist hands during the English civil war, but eventually the stone was taken for use in local buildings leaving the ruin you can see today.

There is a good view of the cathedral town of Wakefield, situated on the River Calder, from the hill at Sandal Castle.