Nobody could have really predicted the impact of Hurricane Sandy, which struck Manhattan on October 29, 2012. If you told us a year ago that a hurricane would shut down all of New York City for weeks and that the hospital would be closed for months, we never would have believed it. Six months later, things still have not completely returned to normal.

Nobody could have really predicted the impact of Hurricane Sandy, which struck Manhattan on October 29, 2012. If you told us a year ago that a hurricane would shut down all of New York City for weeks and that the hospital would be closed for months, we never would have believed it. Six months later, things still have not completely returned to normal.

It all began on what seemed like an ordinary Friday afternoon, as we hurried between clinical duties and research meetings to get some semblance of order before the Halloween weekend. In the midst of the daily hubbub, emails and texts began pouring in about Hurricane Sandy, a massive tropical storm that was projected to hit New York City directly. All 3 hospitals served by the New York University (NYU) are located right along the water in Manhattan and many of the employees live nearby, causing significant concern.

As the storm approached, the lines at the local grocery and convenience stores grew exponentially, wrapping around aisles and often out the door and down the street. Shoppers filled carts with everything from toilet paper and toothpaste, to bottled water and batteries. As soon as their inventory was sold out, shop owners locked their doors and boarded up their windows in preparation for the storm.

When the meteorologists’ worst predictions appeared to be imminent, a mandatory evacuation order was issued for parts of east and southeast Manhattan. The inhabitants of these neighborhoods, many of which included the faculty, staff, residents, and medical students of NYU, migrated to the homes of friends and family. Others, whose apartments were just outside the evacuation zone, hunkered down for what was going to be a long, dark, cold, and wet night.

A few hours after the storm began to hit Manhattan, a massive explosion rocked the electric plant that supplies power to the lower half of Manhattan. Suddenly the skyline was transformed as half of New York City went completely dark, from 39th Street all the way to the southern tip of Battery Park. Without power, there was no electricity, no heat, and no hot water. The winds howled, uprooting trees and tearing down street signs, all while the rain flew sideways. The streets lining the East River flooded early and slowly rescinded overnight, leaving a wake of debris. When morning came, the residents of Manhattan peered out their windows to investigate the damage of the storm, not knowing what to expect.

The New York University (NYU) Department of Urology covers 3 hospitals. The Manhattan VA Hospital was evacuated in advance of the storm, with all of the patients transferred to other veterans’ hospitals in neighboring cities. Bellevue Hospital and NYU Langone Medical Center initially continued to operate during the storm, but were ultimately evacuated when the emergency power supply failed. Many of you may have seen the dramatic TV footage of babies from the ICU being ventilated while carried by nurses down the dark staircases to evacuate the hospital. The efforts made by the clinical staff to ensure patient safety during that time were truly heroic.

In the first few days after the storm, the lower half of Manhattan was like a war zone. With all of the skyscrapers, many people had to walk up and down 10-30 flights of stairs in the dark to look for food or supplies. Some of the elderly people in our neighborhood were unable to do this, so they literally sat in a dark apartment for >10 days eating whatever food remained in the pantry. There was also intermittent internet and cell phone service in the area, leaving people with a very eerie and disconnected feeling. The streets were mostly desolate, with many stores closed and some of them looted. Sanitation was another issue. Without any running water, many people used small amounts of their precious bottled water to flush the toilet once a day. Bags of refuse were carried up and down the dark staircases for disposal. And this is New York, what some (New Yorkers at least) would consider the “center of the universe!” With the world usually at your fingertips, many New Yorkers have never had to think about survival skills. Of course, CNN and other TV news stations featured all kinds of seemingly helpful tips during Hurricane Sandy on how to manage without electricity or running water, but most people who desperately needed this information had no way to watch these segments. Instead makeshift cell phone charging stations were set up along the street for desperate residents hoping to reconnect.

In the first few days after the storm, the lower half of Manhattan was like a war zone. With all of the skyscrapers, many people had to walk up and down 10-30 flights of stairs in the dark to look for food or supplies. Some of the elderly people in our neighborhood were unable to do this, so they literally sat in a dark apartment for >10 days eating whatever food remained in the pantry. There was also intermittent internet and cell phone service in the area, leaving people with a very eerie and disconnected feeling. The streets were mostly desolate, with many stores closed and some of them looted. Sanitation was another issue. Without any running water, many people used small amounts of their precious bottled water to flush the toilet once a day. Bags of refuse were carried up and down the dark staircases for disposal. And this is New York, what some (New Yorkers at least) would consider the “center of the universe!” With the world usually at your fingertips, many New Yorkers have never had to think about survival skills. Of course, CNN and other TV news stations featured all kinds of seemingly helpful tips during Hurricane Sandy on how to manage without electricity or running water, but most people who desperately needed this information had no way to watch these segments. Instead makeshift cell phone charging stations were set up along the street for desperate residents hoping to reconnect.

Mass confusion ensued. Many people’s homes and cars were flooded or destroyed. Military vehicles began to appear around the city to help restore order. The hospitals remained closed and patients were dispersed. There was no way to access the electronic medical record to find out the names and contact information for patients on the upcoming schedule. Even the institutional email system was down, so employees didn’t know when, where or if they needed to report to work. Insurance companies had their work cutout for them. Some even went to the extent of reducing their rates on new insurances and provided the cheapest van insurance and car insurances to the new policy holders. Collision repair technicians fix the outer body of cars. These technicians can also be trained in repairing internal components of a damaged automobile. Formal training is not always required, as many repair shops train employees on the job, but obtaining a degree or certification can assist in employment prospects. For people who owns a car, getting an insurance for it is a matter to be given a deep thought. Everyone knows that car insurance costs high, yet, important. The idea behind this gives the reason why premiums are a very dear commodity. However, in this new age of car insurances, a new type of car policy is born! This is one of the short-term insure companies introduced and termed the car insurance for one week. A car only insured for a one-week period. with this short coverage, the user or buyer of this insurance is not being prompted with so much requirements, unlike the regular or normal car policy in which many documentary, unlike the regular or normal car policy in which many documentary requisites are being asked to be prepared. Click here to find more about the author.

Mass confusion ensued. Many people’s homes and cars were flooded or destroyed. Military vehicles began to appear around the city to help restore order. The hospitals remained closed and patients were dispersed. There was no way to access the electronic medical record to find out the names and contact information for patients on the upcoming schedule. Even the institutional email system was down, so employees didn’t know when, where or if they needed to report to work. Insurance companies had their work cutout for them. Some even went to the extent of reducing their rates on new insurances and provided the cheapest van insurance and car insurances to the new policy holders. Collision repair technicians fix the outer body of cars. These technicians can also be trained in repairing internal components of a damaged automobile. Formal training is not always required, as many repair shops train employees on the job, but obtaining a degree or certification can assist in employment prospects. For people who owns a car, getting an insurance for it is a matter to be given a deep thought. Everyone knows that car insurance costs high, yet, important. The idea behind this gives the reason why premiums are a very dear commodity. However, in this new age of car insurances, a new type of car policy is born! This is one of the short-term insure companies introduced and termed the car insurance for one week. A car only insured for a one-week period. with this short coverage, the user or buyer of this insurance is not being prompted with so much requirements, unlike the regular or normal car policy in which many documentary, unlike the regular or normal car policy in which many documentary requisites are being asked to be prepared. Click here to find more about the author.

Over time, the city gradually started to reopen. A limited bus service began working at no charge, but the lines were several blocks long and the crowding was extreme. Most of the subway stations were flooded and it took several weeks to months for the subway and train services to be restored. There were also gas shortages leading to rationing. People had to wait for 2+ hours in line at the gas station, resulting in crazy stories like this one where a man pulled out a gun to jump the line.

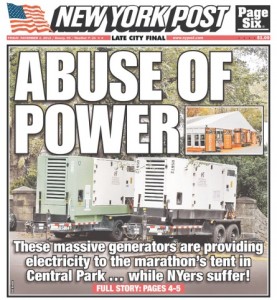

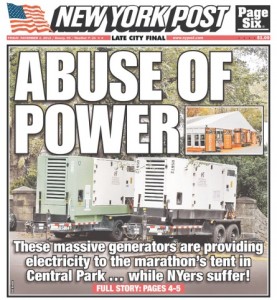

Meanwhile, as soon as the airports reopened many foreigners began arriving into the midst of this scene for the New York City Marathon, which was supposed to take place the following weekend. With half of New York City flooded and in the dark, a huge controversy erupted over diverting scarce resources to allow the marathon to proceed. The New York Post ran a cover story exposing how power generators were being used to prepare the media tents for the marathon, and the race was ultimately cancelled <48 hours beforehand – too late for the many foreign runners who wasted huge sums of money and time making their way to storm-ravaged NYC unnecessarily.

Meanwhile, as soon as the airports reopened many foreigners began arriving into the midst of this scene for the New York City Marathon, which was supposed to take place the following weekend. With half of New York City flooded and in the dark, a huge controversy erupted over diverting scarce resources to allow the marathon to proceed. The New York Post ran a cover story exposing how power generators were being used to prepare the media tents for the marathon, and the race was ultimately cancelled <48 hours beforehand – too late for the many foreign runners who wasted huge sums of money and time making their way to storm-ravaged NYC unnecessarily.

On the clinical side, many NYU physicians obtained emergency privileges to practice in New Jersey. Nevertheless, this involved a long commute (>1 hour) for both patients and physicians to unfamiliar surroundings. In addition, most of these hospitals already operate at capacity. Office space was not available for the “displaced physicians” and it was often difficult just to find a free computer to use. Imagine if the entire staff from another hospital was suddenly transferred to your hospital – where would you put them and how could you accommodate their patients? Many surgeries could only be booked on nights or weekends when the OR was not in use by the local physicians, and could be bumped at the last minute. On-call coverage had to be reorganized to provide care for our patients all over the tri-state area, which was particularly challenging without the regular train and bus services to these areas. Bellevue and NYU Hospital began to partially reopen at the end of December 2012, and the Manhattan VA remained completely closed until March 2013. Even now, some of the clinical services at these hospitals have not been completely restored as the long repair process continues.

From the research standpoint, the impact was huge. Loss of the emergency generators caused many precious research experiments to be lost. Imagine if you collected special samples from around the world for your laboratory, or if you had stored tissue from patients with 20 years of follow-up data. Then one day a big storm came and it all washed away. Some of these things simply cannot be replaced. The situation was similarly bleak for clinical research since the server was also destroyed, resulting in massive data losses. Imagine that you got a grant, hired research personnel, completed several years of data collection and analysis, and even saved an extra copy of your work on the backup server, but suddenly all of that was gone. You could apply for an extension on your grant or insurance money for what was lost in the natural disaster, but it could take years to get back to where you were and this type of intellectual property loss is difficult to even quantify. The original personnel may not be available to re-do the work, the idea may no longer be timely, and what you really want to do is move forward with your research not spend months to years repeating what was already done.

What can we learn from this? Unfortunately, natural disasters happen, and many of the issues that transpired are impossible to predict or prevent, particularly at the individual level. If there are warnings about a major storm, take it very seriously. Keep a section in the closet with some basic supplies like batteries, flashlights, a radio and an emergency list of contacts. Make sure that all electronic devices are fully charged and that your data are backed up as much as possible in different locations. And hope that nothing like this ever happens again.

Dr. Stacy Loeb is an Assistant Professor of Urology and Population Health at New York University and is a Consulting Editor for BJUI. Follow her on Twitter @LoebStacy

Dr. Marc Bjurlin is a Fellow in Urologic Oncology at New York University.

Comments on this blog are now closed.