We describe here the symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment of a pheochromocytoma in the urinary bladder.

Authors: Song Wu1,2, Yingying He1, Kai Yao4, Yongqin Lai2, Zhiming Cai3, Fangjian Zhou4

1 Anhui Medical University, Hefei 230022, An Hui, China

2 Institute of Urology, Shenzhen PKU-HKUST Medical Center, Shenzhen 518036, Guangdong, China

3 The First Hospital of Shenzhen University, Shenzhen 518036, Guangdong, China

4 Department of Urology, Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center, Guangzhou 510060, Guangdong, China

Corresponding Author: Fangjian Zhou, Email: zhoufj@sysucc.org.cn and Zhiming Cai, E-mail: caizhiming2000@yahoo.com.cn

Abstract

Pheochromocytoma of the urinary bladder is a rare neoplasm of the chromaffin tissue of the sympathetic nervous system that occurs within the layers of the bladder wall. The diagnosis is based largely on the presence of clinical symptoms related to catecholamine hypersecretion, although the differential diagnosis of carcinoma of bladder must be excluded. The pathological features of benign and malignant tumors overlap so there are no reliable features of malignancy. In the majority of cases, the treatment of choice is surgical resection.

Introduction

Pheochromocytoma is a neoplasm that develops from cells of the chromaffin tissuescells, which are derived from the ectodermic neural systemneuroendocrine system. Most pheochromocytomas are situated within the adrenal medulla[1] and pheochromocytoma of the urinary bladder is rare [2]. At our centers, 432 cases of pheochromocytoma have been managed between December 1999 and December 2010., of whichOf this number, extra-adrenal pheochromocytomas accounted for 16 cases, which and this included three cases of urinary bladder pheochromocytoma. We report and analyze the clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment in a specific case of bladder pheochromocytoma.

Case report

A 62-year-old man presented at midnight with a history of severe hypertension. Further detailed questioning revealed that he had been experiencing occasional attacks of a throbbing headaches and palpitations associated with micturition at midnight as his only other symptoms. The headaches and palpitations started approximately 2 minutes after urination, and continued for approximately 3 minutes. He was asymptomatic in between these episodes.

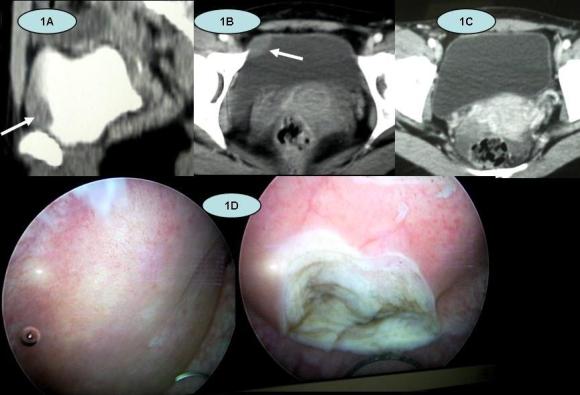

His medical, surgical, and family histories were significant only for a positive history of diabetes. On examination he was thin, with a pulse of 86 beats per minute and a blood pressure of 115/80 mmHg. Ultrasonography showed a mass in his urinary bladder wall that measured 2 × 2 cm (Figure 1), which was confirmed on computed tomography (CT) scan (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Ultrasonography showing a heterogeneous mass located in the bladder dome, and Ultrasound of the urinary bladder revealed a vascular, nearly homogenous mass in the anterior wall of the urinary bladder (arrow).

Figure 2. CT showing tumour located in the anterior front of the bladder with well

This scan also showed that his adrenal glands were completely normal. The results of routine laboratory examinations (full blood count, blood chemistry, coagulation studies, and urinalysis) were within normal limits. His plasma metanephrine was 0.25 nmol/L (normal range at our hospital laboratory, 0.00–0.49 nmol/L) and plasma normetanephrine 4.50 nmol/L (normal range, 0.00–0.89 nmol/L). Vanillylmandelic acid (VMA) in a 24-hour urine collection was normal (20 μmol/24 hours, with a control of 10–35 μmol/24 hours). His chest radiograph and electrocardiogram were normal.

He was diagnosed with a urinary bladder pheochromocytoma and underwent partial cystectomy. During the surgery, his arterial blood pressure was stable and within normal limits. An extended partial cystectomy was performed because the tumor was involving the whole thickness of the bladder wall and the peritoneum covering the bladder wall at the site where the tumor was located. In view of this, to completely remove the tumor, a part of the peritoneum covering the bladder was also removed (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Postoperative specimen: the mass showed pink and inhomogeneity

To our knowledge, this is the first case of a bladder pheochromocytoma managed with extended partial cystectomy.

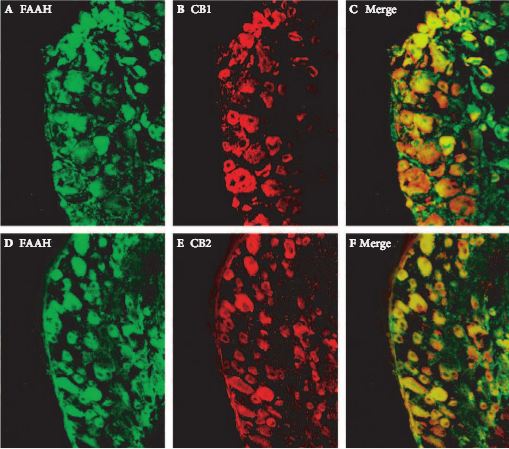

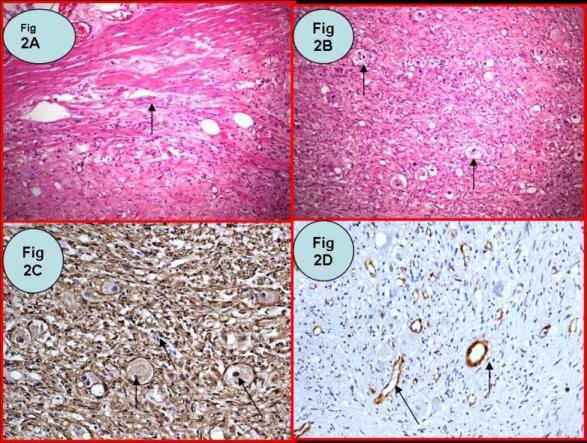

Pathological evaluation revealed that the tumor was a paraganglioma. On histopathological examination, the tumor cells were arranged in a nested pattern (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Tumors proliferation composed of small cells associated to endocrine visualization. (4 a,b: HES x 200; 4 c,d: HES x 400)

The tumor cells showed strong positive enhancement with S-100 (Figure 5a), synaptophysin (Figure 5b), CD56 (Figure 5c), and k-167 (Figure 5d), while immunostaining for CK7, P53, PSA, and P63 was negative. The patient recovered uneventfully and his symptoms related to micturition at midnight disappeared.

Figure 5. (a) Immunostaining for S-100 is strongly positive (DAB ×400). (b) Immunostaining for synaptophysin is positive (DAB ×400). (c) Immunostaining for CD56 is positive (DAB ×400). (d) Immunostaining for k-167 is strongly positive (DAB ×400).

The procedures of this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the World Medical Association. Our Institutional Review Board approved this retrospective study, and informed consent was waived.

Discussion

Pheochromocytoma of the urinary bladder was first reported in 1953 by Zimermana Zimmerman [3] and to date about 300 cases have been reported in the literature. Pheochromocytoma of the urinary bladder accounts for less than 1% of pheochromocytomas in humans and less than 0.06% of bladder tumors [4,5].

The symptoms of bladder pheochromocytoma, such as headaches, palpitations, dizziness, and sweating, are similar to those of adrenal pheochromocytoma. However, the symptoms are usually associated with micturition or defecation. Gross or microscopic hematuria was noted in 60% of patients with bladder pheochromocytoma. The hypertensive crises result from excessive catecholamine secretion, which usually accompanies voiding [6,7] . Other symptoms such as dysuria or suprapubic pain are rare. It has been reported that 17% of bladder pheochromocytomas are hormonally nonfunctional and asymptomatic [8,9] .

Our patient presented with paroxysmal hypertension and symptoms related to excessive catecholamine secretion only when he got up to urinate at midnight. This might be explained by the following: (i) the low probability that this was a functional tumor or the small size of the tumor; (ii) his sympathetic nervous system being more excitable when he woke up at midnight; or (iii) the peritoneum being closely attached to the bladder tumor, so that the tumor was easily stimulated by stretching when he got up to urinate at midnight.

The diagnosis of pheochromocytoma is generally established by measurement of catecholamines in plasma, and catecholamine metabolites (metanephrine and normetanephrine) in a 24-hour urine collection.

On ultrasonography, pheochromocytomas appear as solid masses or contain foci of hemorrhage and necrosis. CT can detect larger bladder tumors, but its sensitivity is just 82%. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is superior to CT in locating tumors and differentiating them from surrounding structures. In 2010, Wang reported the use of MRI in the diagnosis of a bladder paraganglioma [10] . He found that homogeneous T1 hyperintensity was a diagnostic characteristic of bladder paraganglioma on MR imaging, and that necrosis, oval shape, and lower apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values provided further support for the diagnosis of bladder paraganglioma.

Surgical removal of the tumor was the most effective treatment for bladder pheochromocytoma. In the report of Das et al. with 100 cases of bladder pheochromocytoma, partial cystectomy accounted for 84% and total cystectomy 7% of the treatments performed [11] . Transurethral resection was performed in about 7% of cases as an alternative for small and well-defined lesions. It was unclear if there was any advantage for total cystectomy over partial cystectomy in terms of disease control. As the majority of tumors (94%) involve the muscularis propria of the bladder wall, it has been proposed that transurethral resection is insufficient and that partial cystectomy remains the first-choice treatment for bladder pheochromocytomas[12-15]. We believe that extended partial cystectomy is sufficient to control the disease in patients with lesions that involve the whole thickness of the bladder wall, and that total cystectomy, which impairs patient quality of life is not necessary.

Conclusion

A case of bladder pheochromocytoma with symptoms related to increased catecholamine release after urination at midnight only was successfully treated with extended partial cystectomy.

References

1. Zhou M, Epstein JI, Young RH: Paraganglioma of the urinary bladder: a lesion that may be misdiagnosed as urothelial carcinoma in transurethral resection specimens. Am J Surg Pathol 2004;28:94-100.

2. Kovacs K, Bell D, Gardiner GW, et al:Malignant paraganglioma of the urinary bladder: Immunohistochemical study of prognostic indicators. Endocr Pathol 2005; 16:363-369.

3. Zimmerman IJ, Biron RE, MacMmahon HE: Pheochromocytoma of the urinary bladder. N Engl J Med 1953; 249:25-26.

4. Whalen RK, Althausen AF, Daniels GH: Extraadrenal pheochromocytoma. J.Urol. 1992;147:1-10.

5. Sweetser PM, Ohl DA, Thompson NW: Pheochromocytoma of the urinary bladder. Surgery 1991;109:677-681.

6. Whalen RK, Althausen AF, Daniels GH: Extraadrenal pheochromocytoma. J.Urol 1992;147:1-10.

7. Gyftopoulos K, Perimenis P, Ravazoula P: Pheochromocytoma of the urinary bladder presenting only with macroscopic hematuria. Urol Int 2000;65:173-5.

8. Piedrola G, Lopez E, Rueda MD, et al:Malignant pheochromocytoma of the bladder: current controversies. Eur Urol 1997;31: 122-5.

9. Xu DF, Chen M, Liu YS:Non-functional paraganglioma of the urinary bladder: a case report.J Med Case Reports 2010,4:216.

10. Haiyi W , Huiyi Y , Zhiwei F,et al:Bladder paraganglioma in adults: MR appearance in four patients.Eur J Radiol 2010;10:4972-4976.

11. Das S, Bulusa NV, Lowe P:Primary vesicle vesical pheochromocytoma. Urology 1983;21:20-5.

12. Piedrola G, Lopez E, Rueda MD, et al: Malignant pheochromocytoma of the bladder: current controversies. Eur Urol 1997;31: 122-5.

13. Naqiyah, Dohaizak M, Meah F:Pheochromocytoma of the urinary bladder. Singapore Med.2005;46:344-346.

14. Dilbaz B, Bayoglu Y, Oral S,et al: Laparoscopic resection of urinary bladder paraganglioma: a case report. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2006; 16:58-61.

15. Ikeda M, Endo F, Shiga Y, et al:Cystoscopy-assisted partial cystectomy for paraganglioma of the urinary bladder. Hinyokika Kiyo 2008, 54:611-614.

Date added to bjui.org: 20/09/2011

DOI: 10.1002/BJUIw-2011-032-web