Obstructing Calculi within the Male Urethra

Calculi within urethral diverticula are a rare manifestation of urinary stone disease. We report a case of a 63-year-old male presenting with lower urinary tract symptoms, who was subsequently found to have two large calculi located within corresponding urethral diverticula. The patient underwent open urethrotomy, stone extraction, and primary repair of associated urethral diverticula. The patient’s recovery was uneventful with resolution of urinary symptoms six weeks after surgery.

Authors: Kim, Dae Y.; Le, Brian V.; Dupree, James M.; Newman,Jessica; Dreyfuss, Justin C.; Helfand, Brian T.; Gonzalez, Chris M.

Corresponding Author: Gonzalez, Chris M.

Corresponding Author

Chris M. Gonzalez, MD, MBA

Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine

Department of Urology

303 E. Chicago Ave., Tarry 16-703

Chicago, IL 60611

P: 312-908-8145

F: 312-908-7275

E: cgonzalez@nmff.org

Abstract

Calculi within urethral diverticula are a rare manifestation of urinary stone disease. We report a case of a 63-year-old male presenting with lower urinary tract symptoms, who was subsequently found to have two large calculi located within corresponding urethral diverticula. The patient underwent open urethrotomy, stone extraction, and primary repair of associated urethral diverticula. The patient’s recovery was uneventful with resolution of urinary symptoms six weeks after surgery.

Introduction

Incidence

In the Western Hemisphere, a urethral calculus within a diverticulum is a rare clinical entity as compared to developing nations where male urethral calculi are more common due to the increased incidence of bladder calculi(1). Urethral stones account for less than 1% of all urinary stone disease in the Western Hemisphere(2).

Location

The most common site of urethral calculi is the posterior urethra, but calculi have been reported along the entire urethra(3). The majority of studies have demonstrated a higher prevalence rate of posterior urethra stones with the rate ranging from 50-88% of all urethral calculi(1, 4, 5).

Presentation

The diagnosis can be complicated as some patients are asymptomatic while others present with severe symptoms such as pain in the ano-genital area, dysuria, urinary retention, frequency, dribbling, weak urinary stream, hematuria, urethral discharge, and dyspareunia. Posterior urethral stones can present with pain referred to the perineum or rectum, while anterior urethral stones tend to present with pain at the site of impaction. Rarely, patients present with a palpable mass in the penis or at the peno-scrotal junction. Careful physical examination can assist in determining the location of the calculi as a digital rectal examination can demonstrate a firm mass with posterior urethral stones.

The Case

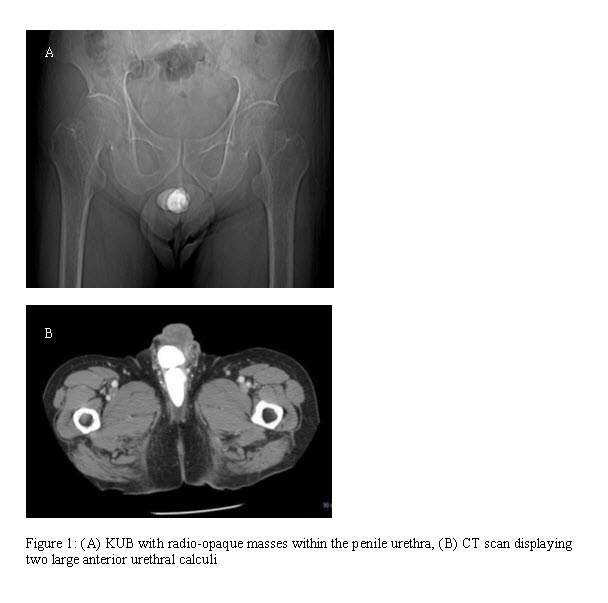

A 63-year-old Asian male with no significant past medical history presented to the emergency department with a four month history of urinary frequency, urgency, nocturia, and a weak stream. These symptoms increased in severity during the previous 7 days, culminating in fever, chills, and scrotal discomfort. The patient denied any previous episodes of urinary tract infectionor stone disease. Physical examination revealed scrotal induration and tenderness with a palpable mass at the peno-scrotal junction. Urine culture was positive for polymicrobial growth with greater than 3 species demonstrated. Doppler ultrasound of the scrotum revealed increased flow to the epididymides and testes consistent with bilateral epididymo-orchitis. Abdominal x ray (Figure 1) and a CT scan demonstrated two masses with high attenuation, measuring 4.3 x 1.8 cm and 2.6 x 2.8 cm within the anterior urethra (Figure 1).

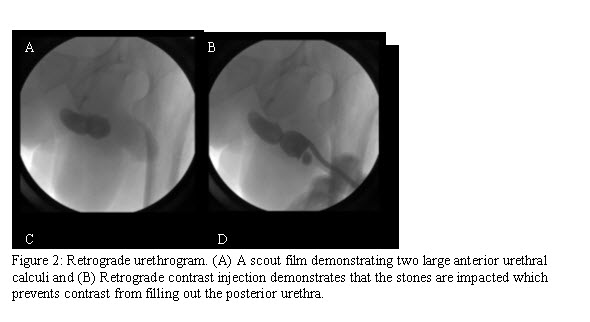

Following a 4-week regimen of antibiotic treatment, the patient underwent cystoscopy with retrograde urethrogram confirming two large calculi within corresponding diverticula at the proximal penile and distal bulb of the urethra (Figure 2). Retrograde manipulation of the calculi into the bladder was unsuccessful due to impaction of the calculi. After unsuccessful cystourethroscopy, open urethrotomy and stone extraction were performed.

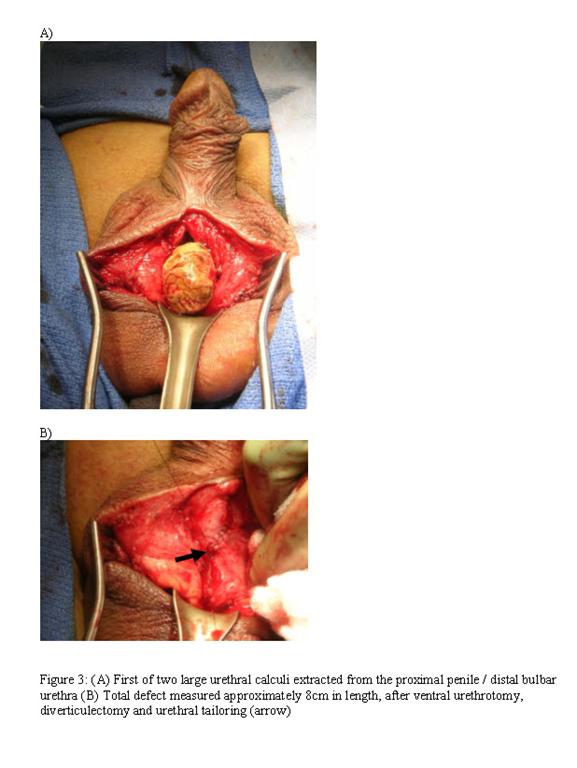

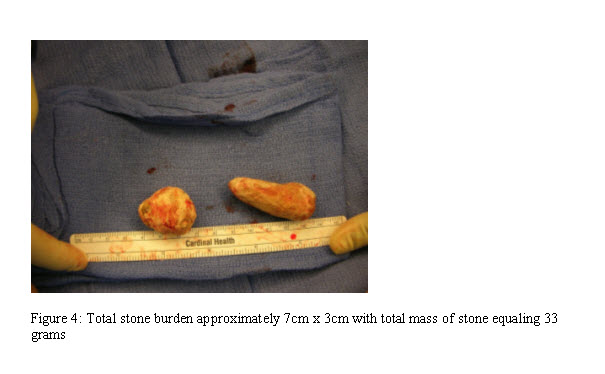

Surgical exploration through a scrotal incision revealed two diverticuli with an enclosed branched calculus. The stones were extracted without difficulty from the surrounding urothelium (Figure 3). Each diverticulum was then subsequently excised and tailored to 26 Fr in circumference utilizing a 5-0 Vicryl suture for primary closure of the urethra. The length of the excision to extract both stones measured 8 cm (Figure 3) with the stone burden approximated at 7 x 3 cm in size (total mass 33 g) (Figure 4). An 18 Fr. Foley catheter was left in place for two weeks, and upon postoperative follow-up at six weeks, the patient had resolution of their urinary symptoms with an International Prostate Symptom Score of 2. Stone composition was determined as calcium carbonate apatite with pathological evaluation of the excised urethral diverticulum identified as benign urethral and periurethral tissue.

Discussion

Etiology

The etiology of urethral calculi can be classified as either originating within the urethra itself (de novo) as a result of an anatomical abnormality, or from distal stone migration from the bladder or upper urinary tracts(3). The normal adult urethra has a diameter of 30 F and therefore should technically allow passage of stones <10 mm; however, the presence of strictures, previous manipulation, or congenital abnormalities decrease urethral diameter and allow trapping of stones(5). Urethral calculi originating de novo are most commonly associated with urethral diverticuli, strictures, schistosomiasis, or neurogenic bladder, the latter of which predisposes patients to urinary stasis and infection(6). The frequency of urethral abnormalities associated with these calculi has been estimated to be as high as 56% of patients(1, 5, 7).

Kamal et al. examined 51 patients with urethral stones and found 86% of patients with calcium oxalate stones, 6% with struvite stones, and 2% with uric acid stones(1). As in the present case, the calcium carbonate calculi likely originated within a pre-existing diverticulum at the peno-scrotal junction.

Diagnostic Evaluation

Diagnostic evaluation of urethral calculi include imaging, such as ultrasound and CT-scan, along with direct visualization modalities via cystourethroscopy. Ultrasonography is a non-invasive diagnostic tool that may be useful for the screening of non-opaque posterior urethral calculi(4).Sonography can be used to demonstrate an echogenic area with acoustic shadowing representing the calculi. Plain X-rays of the abdomen, pelvis, and entire course of the urethra can be used to identify and measure radio-opaque stones.

Treatment and Management

Management of urethral stones depends on their size, location, and elucidation of relevant anatomic abnormality which predisposed their formation. Occasionally non-invasive measures are attempted first in patients without urethral obstruction or spiked calculi, including spontaneous expulsion and milking. Instillation of 2% lidocaine jelly in the urethra has been reported to aid spontaneous passage of stones, and has been associated with success rates ranging from 14.8% to 77.7%(8, 9).

Posterior urethral calculi have been managed with retrograde manipulation of the stone into the bladder either by external physical manipulation, Foley catheterization, or endoscopic guidance. Subsequently, litholopaxy is achieved using transurethral fragmentation with mechanical, ultrasonic, hydraulic, or laser energy. There is high success rate using this combination of retrograde stone manipulation into the bladder and holmium lithotripsy(10).

Stones within the anterior urethra naturally tend to be treated in a different fashion based on anatomy. For example, a meatotomy can be used for impacted stones within the fossa navicularis. For impacted urethral calculi, as in the present case, successful extraction of each large urethral calculus using open urethrotomy, diverticulectomy, and tailoring of the urethra resulted in successful removal of the stones and ultimate resolution of urinary symptoms. This procedure should strongly be considered in the unusual circumstance of large palpable calculi within the anterior urethra.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this case is unusual in that a patient presented with large urethral calculi that manifested as a palpable mass associated with symptoms of urinary obstruction and infection. Although rare, urethral calculi should be included in the differential of any patient presenting with acute urinary retention. Treatment options are based on stone size, shape, location, and associated urethral anatomical pathology. After surgical removal and correction, our patient had a favorable outcome on follow-up with correction of voiding symptoms and without recurrence of calculi to date.

References

[1] Kamal BA, Anikwe RM, Darawani H, Hashish M, Taha SA. Urethral calculi: presentation and management. BJU Int. 2004; 93: 549-52.

[2] Larkin GL, Weber JE. Giant urethral calculus: a rare cause of acute urinary retention. J Emerg Med. 1996; 14: 707-9.

[3] Kaplan M, Atakan IH, Kaya E, Aktoz T, Inci O. Giant prostatic urethral calculus associated with urethrocutaneous fistula. Int J Urol. 2006; 13: 643-4.

[4] Koga S, Arakaki Y, Matsuoka M, Ohyama C. Urethral calculi. Br J Urol. 1990; 65: 288-9.

[5] Selli C, Barbagli G, Carini M, Lenzi R, Masini G. Treatment of male urethral calculi. J Urol. 1984; 132: 37-9.

[6] Hayashi Y, Yasui T, Kojima Y, Maruyama T, Tozawa K, Kohri K. Management of urethral calculi associated with hairballs after urethroplasty for severe hypospadias. Int J Urol. 2007; 14: 161-3.

[7] Sharfi AR. Presentation and management of urethral calculi. Br J Urol. 1991; 68: 271-2.

[8] el-Sherif AE, Prasad K. Treatment of urethral stones by retrograde manipulation and extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy. Br J Urol. 1995; 76: 761-4.

[9] Takasaki E, Suzuki T, Honda M, Imai T, Maeda S, Hosoya Y. Chemical compositions of 300 lower urinary tract calculi and associated disorders in the urinary tract. Urol Int. 1995; 54: 89-94.

[10] Maheshwari PN, Shah HN. In-situ holmium laser lithotripsy for impacted urethral calculi. J Endourol. 2005; 19: 1009-11.

Date added to bjui.org: 12/10/2012

DOI: 10.1002/BJUIw-2012-068-web