We report a case in a elderly female who presented with symptomatic BH causing obstruction of the right renal pelvis and ureter.

Authors: Vikram Balakrishnan, MBBS, BMedSc, Dip. Surg Anatomy; Gregory Neerhut MBBS, FRACS.

Urology Unit, Geelong Hospital, Victoria, Australia

Corresponding Author: Vikram Balakrishnan, Urology Unit, Geelong Hospital, Victoria, Australia. T: +613 421 709 541 Email: vikram_bala@hotmail.com

Introduction

Bochdalek hernia (BH) is a congenital hernia of the diaphragm that occurs in 1 in every 2200 to 12,500 births with an overall prevalence in adults of between 0.17% and 10.5% [1-4]. It results from developmental failure of the posterolateral diaphragmatic foramina to fuse properly and most commonly presents during the neonatal period [5]. Adult patients presenting with symptomatic BH, especially on the right side, are exceedingly rare, and there have been less than 20 cases reported in the literature [6,7]. We report a case in a elderly female who presented with symptomatic BH causing obstruction of the right renal pelvis and ureter.

Case Report

An 83 year old female presented to the emergency department with severe right flank pain on a background of a 12 month history of intermittent mild flank pain. Her past history included chronic renal impairment and right renal colic. Clinical examination revealed a frail elderly lady with normal vital signs. There was some mild flank tenderness on the right and respiratory examination was normal. Creatinine was chronically elevated at 192umol/L, eGFR was 23mL/min, white cell count was 12.0 10^9g/L (reference rage 4-11.0 x10^9 g/L) and the urine was sterile. Plain radiographs of the abdomen demonstrated degenerative changes of the lumbar spine consistent with osteoarthritis and there was no evidence of kidney stones. The patient was discharged with a presumptive diagnosis of chronic back pain.

At outpatient follow-up, the patient had ongoing flank pain and ultrasound demonstrated normally sized and positioned kidneys with hydronephrosis of the right collecting system and a renal pelvis measuring 6cm in diameter. A computerised tomography (CT) scan demonstrated a small BH of the posterior aspect of the right diaphragm. The dilated renal pelvis was drawn superiorly through the hernia into the thorax with the pelviureteric junction located superior to the remainder of the collecting system. The ureter then passed inferiorly through the neck of the Bochdalek hernia back into the abdomen. There was no dilatation of the ureter below the hernia (Figure 1 and 2).

Figure 1. Axial CT scan demonstrates dilated right renal pelvis drawn superiorly through the diaphragmatic hernia

Figure 2. Coronal CT scan demonstrates distended ureter and renal pelvis above the neck of the Bochdalek hernia and normal calibre ureter below

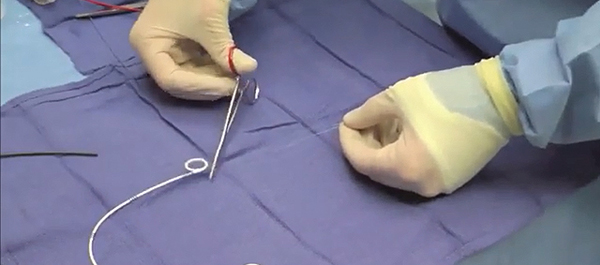

Rigid cystoscopy and a right retrograde pyelogram demonstrated superior and medial deviation of the proximal ureter with kinking of the ureter and proximal hydronephrosis (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Retrograde pyelogram pre and post double J stent placement

A guide-wire was passed to the renal pelvis without difficulty and a 6 French double J stent was placed. The patient’s pain resolved immediately, she made an uneventful recovery and was discharged home the following day. The stent is changed electively every six months and 12 months following presentation she remains pain free.

Discussion

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia was first described by Vincent Alexander Bochdalek in 1848 and results from incomplete closure between the pars lumbaris and pars costalis parts of the diaphragm during fetal development [5,8]. The majority of patients present during neonatal life with concomitant congenital pulmonary abnormalities and consequently have a poor prognosis [1]. Adult presentation with symptomatic BH is rare with approximately 100 cases reported in the literature. Whilst asymptomatic BH tend to occur equally on the right and left hand sides of the diaphragm [3,4], symptomatic BH tend to occur on the left with a ratio of 9:1 [1,2]. The contents of BH depend on the side of the hernia and have included liver, omentum, bowel, spleen, kidneys and stomach [1,10]. The presence of renal pelvis or ureter within a BH is exceedingly rare with only three cases reported in the literature [11-13].

The clinical presentation of BH in adults ranges from an incidental finding on imaging to strangulation of intra-abdominal contents with significant morbidity and mortality. Symptoms are often non-specific and include abdominal pain, dyspnea, chest pain and nausea and vomiting [10]. Of the three cases reported in the literature on BH containing ureter, one was asymptomatic and was discovered incidentally [11], one presented with right upper quadrant pain [12] and the other presented almost identically to our case with a 12 month history of intermittent flank pain [13]. Precipitating factors are sometimes identified and include any mechanism that increases intra-abdominal pressure, however, the patient in our study did not have any history of chronic cough or constipation.

Diagnosis is ultimately via imaging and CT provides the most accurate and reliable method [2,14]. Discontinuity of the posterior diaphragm is usually clearly identified and protrusion of intra-abdominal contents including ureter is clear [2,5,14]. Importantly, CT can identify associated complications of ureteric herniation including hydronephrosis and hydroureter, which is evidenced by dilatation above the hernia neck and a normal calibre ureter below. Of the three reported cases on BH containing ureter, two were associated with obstructive uropathy with similar CT findings to our case [12,13]. Ultrasound, whilst able to identify hydronephrosis in our case, was not able to identify the hernia or the site of obstruction.

The optimal treatment of BH causing obstructive uropathy is unclear. Despite kinking of the ureter we were able to successfully pass a double J stent to the renal pelvis which provided immediate relief of the patient’s symptoms. Similarly, Song et al [14] were able to successfully pass a retrograde stent with follow-up CT confirming resolution of hydronephrosis. Definitive surgical correction of BH is recommended because of the risk of herniation and strangulation of abdominal viscera and excellent outcomes have been described with no evidence of hernia recurrence [10]. In particular, laparoscopic repair with or without mesh appears to be reliable and confers all the benefits of minimally invasive surgery [15]. However, diaphragmatic surgery is not without complications and elderly patients in particular gain only a minimal benefit as the risk of further herniation over their remaining lifetime is low.

Our elderly frail patient was managed with a retrograde ureteric stent. Patients managed this way need to have their stent changed every 6 to 12 months because of the risk of stent encrustation causing obstruction. In addition, these patients should have regular imaging such as chest radiography because, as discussed, clinical symptoms and signs may not correlate with severity of disease. In a younger fitter patient we would recommend surgical correction of the hernia.

Conclusion

We described the case of an 83 year old female presenting with a right sided BH containing the right renal pelvis and ureter causing pain, hydronephrosis and hydroureter. Symptomatic BH in adult patients is rare and there have been only three cases of BH containing ureter in the literature. Ureteric stent offers a safer alternative to surgical repair of the hernia and may be a more appropriate treatment in elderly patients.

References

1. Gedik E, Tuncer MC, Onat S, Avci A, Tacyildiz I, Bac B. A review of Morgagni and Bochdalek hernias in adults. Folia Morphol (Warsz). 2011 Feb;70(1):5-12.

2. Wilbur AC, Gorodetsky A, Hibbeln JF. Imaging findings of adult Bochdalek hernias. Clin Imaging. 1994 Jul-Sep;18(3):224-9.

3. Mullins ME, Stein J, Saini SS, Mueller PR. Prevalence of incidental Bochdalek’s hernia in a large adult population. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001 Aug;177(2):363-6.

4. Temizöz O, Gençhellaç H, Yekeler E, Umit H, Unlü E, Ozdemir H, Demir MK. Prevalence and MDCT characteristics of asymptomatic Bochdalek hernia in adult population. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2010 Mar;16(1):52-5. Epub 2009 Dec 28.

5. Sandstrom CK, Stern EJ. Diaphragmatic hernias: a spectrum of radiographic appearances. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2011 May-Jun;40(3):95-115.

6. Rout S, Foo FJ, Hayden JD, Guthrie A, Smith AM. Right-sided Bochdalek hernia obstructing in an adult: case report and review of the literature. Hernia. 2007 Aug;11(4):359-62. Epub 2007 Mar 7.

7. Agrafiotis AC, Kotzampassakis N, Boudaka W. Complicated right-sided Bochdalek hernia in an adult. Acta Chir Belg. 2011 May-Jun;111(3):171-3.

8. Haller JA Jr. Professor Bochdalek and his hernia: then and now. Prog Pediatr Surg. 1986;20:252-5.

9. Bujanda L, Larrucea I, Ramos F, Muñoz C, Sánchez A, Fernández I. Bochdalek’s hernia in adults. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001 Feb;32(2):155-7.

10. Brown SR, Horton JD, Trivette E, Hofmann LJ, Johnson JM. Bochdalek hernia in the adult: demographics, presentation, and surgical management. Hernia. 2011 Feb;15(1):23-30. Epub 2010 Jul 8.

11. Chawla K, Mond DJ. Progressive Bochdalek hernia with unusual ureteral herniation. Comput Med Imaging Graph. 1994 Jan-Feb;18(1):53-8.

12. Song YS, Hassani C, Nardi PM. Bochdalek hernia with obstructive uropathy. Urology. 2011 Jun;77(6):1338. Epub 2010 Jul 1.

13. Paterson IS, Lupton EW. Pelviureteric junction obstruction secondary to renal pelvic incarceration in a congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Br J Urol. 1989 Nov;64(5):548-9.

14. Shin MS, Mulligan SA, Baxley WA, Ho KJ. Bochdalek hernia of diaphragm in the adult. Diagnosis by computed tomography. Chest. 1987 Dec;92(6):1098-101.

15. Palanivelu C, Rangarajan M, Rajapandian S, Amar V, Parthasarathi R. Laparoscopic repair of adult diaphragmatic hernias and eventration with primary sutured closure and prosthetic reinforcement: a retrospective study. Surg Endosc. 2009 May;23(5):978-85. Epub 2009 Mar 14.

Date added to bjui.org: 03/12/2011

DOI: 10.1002/BJUIw-2011-104-web