Every week, the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Week from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to the article itself, there is an editorial written by a prominent member of the urological community, and a video made by the authors. These are intended to provoke comment and discussion and we invite you to use the comment tools at the bottom of each post to join the conversation.

If you only have time to read one article this week, it should be this one.

Benjamin Press*, Andrew B. Rosenkrantz†, Richard Huang‡ and Samir S. Taneja§

*Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, Newark, NJ, †Department of Radiology, ‡Department of Urology, and §Departments of Urology and Radiology, NYU Langone Health, New York, NY, USA

Abstract

Objective

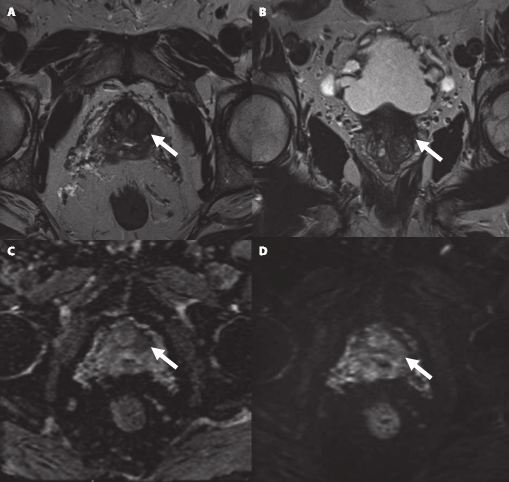

To determine whether the presence of an ultrasound hypoechoic region at the site of a region of interest (ROI) on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) results in improved prostate cancer (PCa) detection and predicts clinically significant PCa on MRI–ultrasonography fusion‐targeted prostate biopsy (MRF‐TB).

Materials and Methods

Between July 2011 and June 2017, 1058 men who underwent MRF‐TB, with or without systematic biopsy, by a single surgeon were prospectively entered into an institutional review board‐approved database. Each MRI ROI was identified and scored for suspicion by a single radiologist, and was prospectively evaluated for presence of a hypoechoic region at the site by the surgeon and graded as 0, 1 or 2, representing none, a poorly demarcated ROI‐HyR, or a well demarcated ROI‐HyR, respectively. The interaction of MRI suspicion score (mSS) and ultrasonography grade (USG), and the prediction of cancer detection rate by USG, were evaluated through univariate and multivariate analysis.

Results

For 672 men, the overall and Gleason score (GS) ≥7 cancer detection rates were 61.2% and 39.6%, respectively. The cancer detection rates for USGs 0, 1 and 2 were 46.2%, 58.6% and 76.0% (P < 0.001) for any cancer, and 18.7%, 35.2% and 61.1% (P < 0.001) for GS ≥7 cancer, respectively. For MRF‐TB only, the GS ≥7 cancer detection rates for USG 0, 1 and 2 were 12.8%, 25.7% and 52.0%, respectively (P < 0.001). On univariate analysis, in men with mSS 2–4, USG was predictive of GS ≥7 cancer detection rate. Multivariable regression analysis showed that USG, prostate‐specific antigen density and mSS were predictive of GS ≥7 PCa on MRF‐TB.

Conclusions

Ultrasonography findings at the site of an MRI ROI independently predict the likelihood of GS ≥7 PCa, as men with a well‐demarcated ROI‐HyR at the time of MRF‐TB have a higher risk than men without.