Urodynamics is acceptable and well-tolerated but best practice is not always provided: lessons from male patients interviewed during the UPSTREAM trial

In a recently published qualitative study, we found that urodynamic testing was acceptable to men with lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), despite some reporting apprehension, discomfort or embarrassment and, at times, inadequate provision of information. Men’s experiences of urodynamics highlight ways in which clinical practice can be improved, including better communication about what to expect during and after the test, minimising embarrassment by ensuring privacy, and timely discussion of test results in sufficient detail.

Ninety percent of men aged 50‐80 live with at least one LUTS, which can negatively impact quality of life. LUTS prevalence and severity increase with age, and with demographic aging the management of LUTS is an increasing priority. Urodynamics with invasive multichannel cystometry is widely used when medications haven’t successfully relieved symptoms and surgery for bladder outlet obstruction is being considered. But there is ongoing debate about the extent to which urodynamics should be used, reflecting lack of evidence regarding the effectiveness of urodynamics and how acceptable it is to patients.

What we did

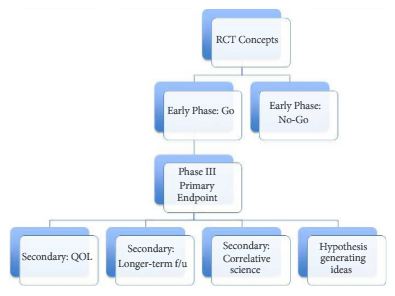

The Urodynamics for Prostate Surgery: Randomised Evaluation of Assessment Methods (UPSTREAM) randomised controlled trial is a 4-year study funded by the National Institute of Health Research Health Technology Assessment Programme (UK). The trial randomised 820 men with LUTS from urology departments in 26 hospitals in England to either a care pathway consisting of non-invasive routine tests, or one of routine tests plus urodynamics. At 18-months after randomisation, UPSTREAM assessed the effect of urodynamics on symptoms and rates of surgery in men with bothersome LUTS seeking further treatment.

In a large qualitative study nested within the UPSTREAM trial, we explored men’s attitudes to and experiences of urodynamics, to provide in‐depth qualitative evidence to inform clinical practice. We interviewed a diverse group of 41 men with LUTS, including those who had had urodynamics and those who had not.

What we found

- All 25 men who underwent urodynamics reported that it was acceptable.

- Of the 16 men who had not had urodynamics previously, 14 said they would have been willing to have it if needed (with four reporting some apprehension), while two said they would want more information about the test and its purpose.

- Among patients who had had urodynamics, the test was well-tolerated, although there was variation in how uncomfortable men found it. Some men experienced short-lived negative after-effects (e.g. stinging, a urinary tract infection), but despite these issues said they would willingly have the test again.

- A minority of men reported embarrassment, due to the intimate nature of urodynamics or not being prepared for its effects (e.g. spraying while urinating).

- Embarrassment also depended on the degree of privacy available, including the number of people in the room during the test, room location and size (a larger room near a busy corridor was more socially awkward).

- Patients valued urodynamics for its diagnostic insight, perceiving it as more informative than other tests. Patients felt that having urodynamics meant they had received all the investigative tests available and so had all possible facts regarding their condition.

- Patients described gaps in the information provided by clinicians before, during, and after the test; for example, what to expect when the test was conducted and what the test results meant.

- How and when results were explained varied: explanations were given during the test by the technician or nurse undertaking it, from a doctor straight after receiving the test, or at a separate appointment with a doctor a short time later. Men appreciated it when test results were available and discussed with a clinician immediately after the test.

- While most men were satisfied with clinicians’ explanation of the results of urodynamics, this was not universal; rushed explanations were highlighted as problematic.

Recommendations

Based on men’s experiences, we recommend:

- Good communication before and during the procedure, in line with patient preferences, to ensure patients are well prepared and informed.

- Prioritising patient privacy, including minimising the number of people present during the test and introducing the staff members who are present.

- Discussing test results with patients promptly, in the amount of detail they wish.

- Training and guidance for urology clinicians and urodynamics technicians in these areas.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge and thank the patients and clinicians involved in the UPSTREAM trial as well as the NHS trusts involved. This project was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) program (project number 12/140/01). This study was designed and delivered in collaboration with the Bristol Randomised Trials Collaboration (BRTC), a UKCRC registered clinical trials unit which, as part of the Bristol Trials Centre, is in receipt of National Institute for Health Research CTU support funding. The views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the HTA program, NIHR, NHS, or the Department of Health and Social Care.

About the authors:

Dr Selman and Dr Horwood are Senior Research Fellows at University of Bristol, specialising in qualitative research in randomised trials. Twitter: @Lucy_Selman, @JPHorwood

Prof Drake is Professor of Physiological Urology at Bristol Urological Institute, North Bristol NHS Trust, and at Translational Health Sciences, Bristol Medical School, University of Bristol. Twitter: @MarcusDrakeUrol, @UroweESU

Dr Amanda Lewis is a Clinical Trial Manager at the University of Bristol, currently working in the area of Urology research. Twitter: @ALBrooks2015