Posts

Article of the Week: Robotic Surgery – Development Of A Standardised Training Curriculum

Every Week the Editor-in-Chief selects the Article of the Week from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to the article itself, there is an accompanying editorial written by a prominent member of the urological community. This blog is intended to provoke comment and discussion and we invite you to use the comment tools at the bottom of each post to join the conversation.

If you only have time to read one article this week, it should be this one.

Development Of A Standardised Training Curriculum For Robotic Surgery: A Consensus Statement From An International Multidisciplinary Group Of Experts

, , 1, , Abaza2, 3, 4, 5, 6, Barret7, 7, , 8, , 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, PascalRischmann17, 7, 18, 18, Stolzenburg19, 20, uroff21, 22, 23, 16, 1,24, 25, 26, 27, 28, J 26 and

Department of Urology, Medical Research Council (MRC) Centre for Transplantation, King’s College London, Guy’s Hospital, London, UK, 1Department of Urology, OLV Vattikuti Robotic Surgery Institute, OLV Hospital, Aalst, Belgium, 2Department of Urology, The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, Arthur G James Cancer Hospital & Richard J Solove Research Institute, Columbus, OH, USA, 3Medanta – The Medicity, Gurgaon, Haryana, India, 4Department of Urology, University of California, Irvine, Orange, CA, USA, 5Department of Urology, Lund University Hospital, Lund, Sweden, 6Urology Clinic, A.O.U.I. Verona, Verona, Italy, 7Department of Urology, Institut Mutualiste Montsouris, Paris, France, 8Service d’Urologie, Centre Hospitalier Rene-Dubos, Cergy-Pontoise, France, 9Service d’Urologie, CHRU Nancy, Vandoeeuvre-les-Nancy, France, 10University Hospital, Mannheim, Germany, 11Department of Urology, San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Milan, Italy, 12Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre and the Royal Melbourne Hospital, Melbourne, Vic., Australia, 13Department of Urology, Fundacio Puigvert, Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain, 14Global Robotics Institute, Florida Hospital Celebration Health, Celebration, FL, USA, 15Clinique Saint-Augustin, Bordeaux, France, 16Department of Urology, University Hospital, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium, 17Service de Chirurgie Urologique, CHU Purpan, Toulouse, France, 18Klinik fur Urologie und Kinderurologie, Universitatsklinikum des Saarlandes, Homburg/Saar, Germany, 19Department of Urology, University of Leipzig, Leipzig, Germany, 20Department of Urology, Foch Hospital, Suresnes, France, 21Department of Urology, Ulm University Medical Center, Ulm, Germany, 22Service D’Urologie et de Transplantation Réno-Pancréatique, Hôpital Pitié-Salpêtrière, Paris, France, 23Department Urology, Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 24University of Eastern Piedmont, Novara, Italy, 25St. Antonius-Hospital Gronau, Gronau, Germany, 26Department of Oncology and Pathology, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden, 27Division of Urology, City of Hope, Duarte, CA, USA, and 28Department of Urology, University Hospital Carl Gustav Carus, Technical University of Dresden, Dresden, Germany

OBJECTIVES

To explore the views of experts about the development and validation of a robotic surgery training curriculum, and how this should be implemented.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

An international expert panel was invited to a structured session for discussion. The study was of a mixed design, including qualitative and quantitative components based on focus group interviews during the European Association of Urology (EAU) Robotic Urology Section (ERUS) (2012), EAU (2013) and ERUS (2013) meetings. After introduction to the aims, principles and current status of the curriculum development, group responses were elicited. After content analysis of recorded interviews generated themes were discussed at the second meeting, where consensus was achieved on each theme. This discussion also underwent content analysis, and was used to draft a curriculum proposal. At the third meeting, a quantitative questionnaire about this curriculum was disseminated to attendees to assess the level of agreement with the key points.

RESULTS

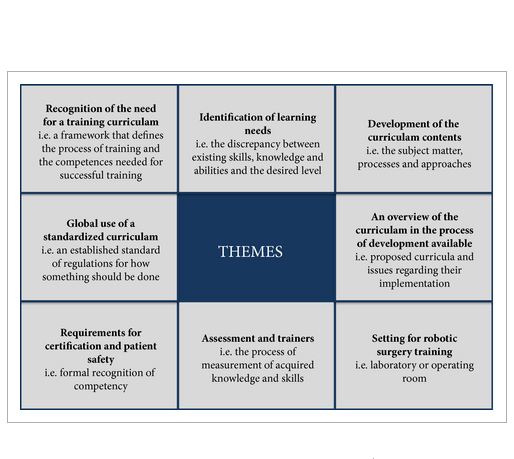

In all, 150 min (19 pages) of the focus group discussion was transcribed (21 316 words). Themes were agreed by two raters (median agreement κ 0.89) and they included: need for a training curriculum (inter-rater agreement κ 0.85); identification of learning needs (κ 0.83); development of the curriculum contents (κ 0.81); an overview of available curricula (κ 0.79); settings for robotic surgery training ((κ 0.89); assessment and training of trainers (κ 0.92); requirements for certification and patient safety (κ 0.83); and need for a universally standardised curriculum (κ 0.78). A training curriculum was proposed based on the above discussions.

CONCLUSION

This group proposes a multi-step curriculum for robotic training. Studies are in process to validate the effectiveness of the curriculum and to assess transfer of skills to the operating room.

Editorial: Towards a Standardized Training Curriculum For Robotic Surgery

The work of the authors [1] towards robotic training and credentialing is much needed and should be applauded as increased scrutiny is being placed on complications associated with robotic surgery [2]. The authors held three separate meetings in 2012 and 2013 in which they identified themes, developed a training curriculum, and assessed expert agreement with their proposed curriculum. The authors’ [1]quantitative survey of 24 experts revealed that all ‘agreed’ or ‘agreed strongly’ with the proposed curriculum. The curriculum includes three areas, cognitive, psychomotor, and teamwork/communication skills, which we feel are vital for good outcomes [3]. As was noted, there are available ‘E-learning’ tools online from organisations such as the AUA and from Intuitive Surgical, and these can be further expanded and validated [4, 5]. The AUA also has recommendations for credentialing requirements that are available online.

We agree with the authors [1] that simulation should include inanimate models, which provide a good cost to benefit ratio. There are increasing numbers of inanimate models for the simulation of procedures, e.g. partial nephrectomy and pyeloplasty. One limitation of inanimate training is that the entire robotic surgical system is used and it may only be free for training on nights and weekends when the robotic systems are not being used clinically. Virtual reality simulators offer a more convenient way to become familiar with the robotic environment, but at a cost of ≈$100 000 (American dollars). Virtual reality simulation is predominantly used to develop skills for a junior trainee or a novice surgeon. However, procedure-specific and augmented-reality simulation is being developed and will greatly enhance robotic training.

The authors [1] should be applauded for offering a specific curriculum consisting of online training, an 8-day ‘discovery’ course for simulation and observation, and a 6-month fellowship for step-wise progression to ‘live’ surgical console time. As the authors note, credentialing should be based on competency and not on the number of cases logged or the duration of training alone. The duration of the fellowship should be based on the learning objectives and research/academic requirements.

In the USA, robotic surgical training is included during residency in urology and a fellowship may not be required if a graduating resident is proficient according to the programme directors’ assessment. For surgeons who have not been trained during residency, proctoring by an experienced surgeon is recommended by the AUA [5], after completing a structured robotic surgical curriculum as described in this article [1]. However, a validated curriculum and benchmarks for competency have not been established. The Fundamentals of Robotic Surgery (FRS) curriculum will be validated during the next year for a multidisciplinary curriculum with skills testing [6].

We also agree with the authors [1] that non-technical skills such as trouble-shooting, teamwork, leadership, and communication are critically important for preventing adverse events. Many if not most complications occur due to failures in patient selection, trocar positioning, and bedside assisting. Also, many complications can be traced to ‘system’ problems rather than console performance. Robotic surgery requires a proficient team to ensure good outcomes.

Currently, there are no uniform credentialing requirements to practice robotic surgery in the USA or many other countries. A validated robotic training curriculum with competency-based assessments is essential and can be integrated into residency programmes where robotic technology is readily available. Where robotic surgical volume is inadequate, fellowship programmes can provide the needed training. A validated competency-based approach offers the hope of better patient outcomes and the continued acceptance of new technologies such as robotic surgery.

and

Department of Urology, Indiana University, Indianapolis, IN, USA

References

1 AhmedK, Khan R, Mottrie A et al . Development of a standardised training curriculum for robotic surgery: a consensus statement from an international multidisciplinary group of experts. BJU Int 2014. [Epub ahead of print]. Doi: 10.1111/ bju.12974.

2 Alemzadeh H, Iyer RK, Raman J. Safety Implications of Robotic Surgery: Analysis of Recalls and Adverse Event Reports of da Vinci Surgical Systems. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Annual Meeting; 2014; Orlando, Florida. Available at: https://www.sts.org/sites/default/files/documents/pdf/annmtg/2014AM/50AM_MonJan27.pdf. Accessed February 2015.

3 Bahler CD, Sundaram CP. Training in Robotic surgery: simulators, surgery, and credentialing. Urol Clin North Am 2014; 41: 581–9.

4 The American Urological Association. E-Learning: Urologic Robotic Surgery Course. The American Urological Association Education and Research, Inc, 2012. Available at: https://www.auanet.org/education/modules/robotic-surgery/. Accessed April 2014.

5 The American Urological Association. Standard Operating Practices (SOP’S) for Urologic Robotic Surgery. The American Urological Association, 2013. Available at: https://www.auanet.org/common/pdf/about/SOP-Urologic-Robotic-Surgery.pdf. Accessed April 2014.

6 Smith R, Patel V, Satava R. Fundamentals of robotic surgery: a course of basic robotic surgery skills based upon a 14-society consensus template of outcomes measures and curriculum development. Int J Med Robot 2014;10: 379–84.

Article of the Week: Learning curves for urological procedures – a systematic review

Every week the Editor-in-Chief selects the Article of the Week from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to the article itself, there is an accompanying editorial written by a prominent member of the urological community. This blog is intended to provoke comment and discussion and we invite you to use the comment tools at the bottom of each post to join the conversation.

If you only have time to read one article this week, it should be this one.

Learning curves for urological procedures: a systematic review

Hamid Abboudi, Mohammed Shamim Khan, Khurshid A. Guru*, Saied Froghi†, Gunter de Win‡, Hendrik Van Poppel§, Prokar Dasgupta and Kamran Ahmed

MRC Centre for Transplantation, King’s College London, King’s Health Partners, Department of Urology, Guy’s Hospital, London, UK, *Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Buffalo, NY, USA, †The Oxford Cancer Centre, Oxford University, Churchill Hospital, Oxford, UK, ‡Department of Urology, University Hospital Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium, and §Department of Urology, University Hospital, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium

OBJECTIVE

- To determine the number of cases a urological surgeon must complete to achieve proficiency for various urological procedures.

PATIENT AND METHODS

- The MEDLINE, EMBASE and PsycINFO databases were systematically searched for studies published up to December 2011.

- Studies pertaining to learning curves of urological procedures were included.

- Two reviewers independently identified potentially relevant articles.

- Procedure name, statistical analysis, procedure setting, number of participants, outcomes and learning curves were analysed.

RESULTS

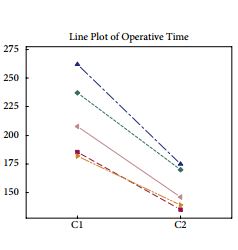

- Forty-four studies described the learning curve for different urological procedures.

- The learning curve for open radical prostatectomy ranged from 250 to 1000 cases and for laparoscopic radical prostatectomy from 200 to 750 cases.

- The learning curve for robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy (RALP) has been reported to be 40 procedures as a minimum number.

- Robot-assisted radical cystectomy has a documented learning curve of 16–30 cases, depending on which outcome variable is measured.

- Irrespective of previous laparoscopic experience, there is a significant reduction in operating time (P = 0.008), estimated blood loss (P = 0.008) and complication rates (P = 0.042) after 100 RALPs.

CONCLUSIONS

- The available literature can act as a guide to the learning curves of trainee urologists. Although the learning curve may vary among individual surgeons, a consensus should exist for the minimum number of cases to achieve proficiency.

- The complexities associated with defining procedural competence are vast.

- The majority of learning curve trials have focused on the latest surgical techniques and there is a paucity of data pertaining to basic urological procedures.

Editorial: Is surgery a never ending learning process?

The concept of the learning curve is one of the most important issues in surgery and also one of the most overlooked. In the present issue of BJUI, Abboudi et al. [1] present an interesting review paper evaluating the concept of the learning curve in urological procedures. Specifically, the authors have conducted a methodologically consistent systematic review on the literature focused on the learning curve of some urological procedures, including mainly radical prostatectomy (RP), robot-assisted partial nephrectomy (RAPN) and percutaneous nephrolitotomy [1]. Surprisingly, nothing was available for BPH treatments, which are among the most prevalent urological procedures.

Most of the studies are focused on robot-assisted RP (RARP), but the available literature is of poor methodological quality, including mainly surgical series evaluating a limited number of surgeons, with a heterogeneous selection of outcomes from which to study the learning curve and a focus on short-term outcomes. Conversely, the literature on retropubic RP or laparoscopic RP is of higher quality, including a few very large multi-institutional studies encompassing the performances of several surgeons (reference nos. 24, 26, 29 and 30 in the review) and adopting sophisticated statistical methodology; however, the current interest for these procedures is quite limited, RARP being more commonly preferred. With the above-mentioned limitations in mind, what we have learnt is that RARP operating time plateaus after 50–200 cases, positive surgical margin (PSM) rates after 50–1600 cases, and continence and potency after 200 cases [1]. Such data are only partially in line with the findings of a recent prospective Australian study [2], not included in the present systematic review, which evaluated the learning curve with RARP of a high-volume open surgeon (>3000 retropubic RPs performed before the study beginning). In that study, Thompson et al. [2] demonstrated that performances with RARP surpassed those with retropubic RP after ∼100 cases for sexual function scores and PSM rates in pT2 cancers, whereas ∼150 cases were needed to reach the same target with urinary function scores. Moreover, RARP performances kept on improving, with sexual and urinary scores plateauing after 600–700 and 700–800 cases, respectively. Similarly, with regard to PSMs, it was demonstrated that PSM rates in pT2 and pT3–4 cancers plateaued after 400–500 and 200–300 cases, respectively [2]. Although improvement is likely, it is not clear how much these performances might improve with further extension of the caseload.

Taken together, those data suggest that even with robotic assistance, a high volume of cases is strongly associated withimproving oncological and functional outcomes after RARP. This is not an extraordinarily original concept, but implies that the daVinci platform, by itself, cannot guarantee excellent surgical quality and that the relevance of the surgeon is as high as ever.

Limited data are available on other major robotic procedures, such as RAPN and robot-assisted radical cystectomy (RARC). Specifically, 20–75 cases are thought to be needed to observe a plateau in warm ischemia time (WIT) during RAPN, which is in line with our previous findings demonstrating a continuous decrease in WIT during the first 50 cases [3]. Similarly, 20–30 cases are supposed to be needed to achieve acceptable operating times, lymph node yields and PSM rates after RARC; however, those findings do not take in account the burden of robotic experience achieved with RARP before embarking in RARC, which is clearly a major issue [4].

Considering that the improvements in performances along the learning curve exceeded any effect sizes we might reasonably expect from a novel drug [5], it is clear that any attempt to centralise treatments for complex procedures in high-volume centres with high-volume surgeons should be attempted. Obviously, that is a very critical target, which is hard to achieve in many realities. In parallel, interventions to improve the performance of surgeons in order to,reduce the learning curve are mandatory. For example, fellowship-trained RARP surgeons have been shown to outperform experienced open or laparoscopic surgeons moving to RARP without specific training [6,7]. For those surgeons for whom fellowship is unfeasible or unpractical, structured courses with integration of simulation, dry laboratory, wet laboratory and da Vinci modular training, for example, using the model of the recently concluded European Robotic Urology Society Pilot Study, can significantly ease the first steps of the learning curve, reducing patients risk. In parallel, intensive courses focused on specific procedures could help those surgeons who had completed the initial steps of their learning curve to master the specific technical details necessary to improve outcomes.

Alexander Mottrie*† and Giacomo Novara†‡

*OLV Vattikuti Robotic Surgery Institute and † Department of Urology, OLV Hospital Aalst, Aalst, Belgium and ‡ Department of Surgery, Oncology and Gastroenterology, Urology Clinic University of Padua, Padua, Italy

References

1 Abboudi H, Khan MS, Guru KA et al. Learning curves for urological procedures: a systematic review. BJU Int 2014; 114: 617–29

2 Thompson JE, Egger S, Böhm M et al. Superior quality of life and improved surgical margins are achievable with robotic radical prostatectomy after a long learning curve: a prospective single-surgeon study of 1552 consecutive cases. Eur Urol 2014; 65: 521–31

3 Mottrie A, De Naeyer G, Schatteman P et al. Impact of the learning curve on perioperative outcomes in patients who underwent robotic partial nephrectomy for parenchymal renal tumours. Eur Urol 2010; 58: 127–32

4 Hayn MH, Hellenthal NJ, Hussain A et al. Does previous robot-assisted radical prostatectomy experience affect outcomes at robot-assisted radical cystectomy? Results from the International Robotic Cystectomy Consortium. Urology 2010; 76: 1111–6

5 Vickers AJ. What are the implications of the surgical learning curve? Eur Urol 2014; 65: 532–3

6 Kwon EO, Bautista TC, Jung H et al. Impact of robotic training onsurgical and pathologic outcomes during robot-assisted laparoscopicradical prostatectomy. Urology 2010; 76: 363–8

7 Leroy TJ, Thiel DD, Duchene DA et al. Safety and peri-operative outcomes during learning curve of robot-assisted laparoscopicprostatectomy: a multi-institutional study of fellowship-trainedrobotic surgeons versus experienced open radical prostatectomysurgeons incorporating robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy. J Endourol 2010; 24: 1665–9

The Urology Foundation SpRUCE course

Last weekend, The Urology Foundation held the Specialist Registrar in Urology Consultant Education (SpRUCE) course in Birmingham. It was spread over 2 days with a networking dinner held in the evening. The course fills a significant void in higher surgical training – that which involves high quality training in interview and communication skills.

In the evening, we were joined by a faculty of senior urologists and professors and were able to network with them over dinner and drinks in a relaxed and informal way. We had an inspiring after dinner speech from BAUS vice-president, Mark Speakman, who stressed the importance of making the most of the connections we make with other urologists. He pointed out that this was not only good for personal career development, but also for patient care. Unlike communication skills trainers I have met in the past, Anna Raine and Jonathan Lermit kept the audience of 22 SpRs captivated throughout the course. They used several techniques to expose where our communication skills were deficient and then introduced us to techniques to improve them. After teaching us about the differences between making a good and an excellent first impression, we moved on to communication styles in interview scenarios. The sessions were highly interactive and our trainers involved the entire group.

The second day was more or less devoted to mock consultant interviews by a panel of urologists and nurses. This was the real highlight of the course. We were split into 4 small groups and each of us was interviewed for approximately 20 minutes. We got a realistic idea of what questions were actually asked in consultant interviews and received detailed feedback from the panel. This was invaluable as it gave a real insight into how others perceived our performance. The interviews were also filmed and we were given the discs to take home and review.

The Urology Foundation provided this course to us for free and it is an excellent example of the good work this charity does in fostering trainees. We all left having learnt a great deal about ourselves and each other and the small size of the group meant we were able to make new friends from all over the UK. I can thoroughly recommend the course to senior trainees and hope TUF continue to run SpRUCE in the future.

Ravi Barod has completed his urological training in London and is about to start a robotic surgery fellowship in the USA. @RaviBarodUrol

Urological Fellowships – the unwritten but almost essential step to a future specialist consultant practice?

Preamble:

Preamble:

Training in urology in the UK, and indeed globally has seen significant changes in the last decade. This has mirrored the changing face of health care provision within and outside the NHS. For award of a Certificate of Completion of Training (CCT), the Joint Committee on Surgical Training (JCST) has recommended specific guideline criteria for different specialties, including urology. The current structure of urological training in the UK has evolved to prepare a trainee by the completion of training at bare minimum for a general urologist. However, depending on the training environment, trainers and trainee enthusiasm with an early focus of interest, many trainees achieve more than just this bare minimum by way of modular training, especially in their final years of training. Some will carry on with acquisition of specialist skills as junior consultants, but increasingly trainees are opting to go for fellowships in their area of specialist interest. This is almost becoming an unwritten essential step for getting a plum specialist post.

When to start?

Those trainees with a special interest in a particular area (and wish to pursue this after CCT) should start the thought process by the end of second year, and their initial groundwork to identify suitable fellowships by third year. Why the rush? Simple reason: the application time to the start of some fellowships typically lags by a year or more. For example, many North American institutional fellowships have application submission deadlines in January, followed by interviews in February-May, for a fellowship that will start in July the following year (18 month lag!). This rush is even more important if the fellowship is intended to be undertaken prior to end of training as an ‘out of programme experience’ or ‘out of programme training’, as the rules have recently changed as of April 2013 where some Local Education and Training Boards (LETBs), previously called ‘Deaneries’, under the Health Education England will not allow OOPE or OOPT in the final year of training. Refer to www.gmc-uk.org and www.hee.nhs.uk for more details on OOPT and OOPE.

When to go on fellowship?

The options are either doing your fellowship before completing training as an OOPE / OOPT or going on a post-CCT fellowship. When to go depends on your individual interest, personal circumstances, fellowship criteria, your choice and importantly the support of your programme director and local surgical training committee. The advantage of an OOPE/OOPT fellowship before CCT is that when you come back, you have your registrar job and salary to come back to. You also don’t lose your grace period at the end of CCT. The disadvantage is that you may come back specialised and ready for a consultant job, but since you haven’t yet completed your full training, you could miss some good job opportunities while you go back to being a registrar for a year. The advantage of a post-CCT fellowship is that you can start looking for jobs during your fellowship and ideally walk into a consultant (or locum consultant) job, but this requires diligently keeping in touch while you are away. The disadvantage is that you may not have anything to come back to, and you lose your grace period. Either way, it’s a gamble.

Where to go?

Traditionally, the two most popular destinations for fellowships are USA and Australia. Emerging spots include Canada, Europe and home-based UK fellowships. Each place has its pros and cons. Australian fellowships, usually for a year, are supposedly good hands-on experience with a fantastic salary package, proportional to frequency of calls. However they grossly lack research and formal learning opportunities. American and Canadian fellowships are usually 2 years with a year of research and a year of clinical/operative work. The research exposure as well as publishing, critical appraisal and exposure to knowledge is fantastic. For US fellowships, trainees have to sit the USMLE and be ECFMG certified. Canadian fellowships are becoming popular with British trainees as holding the FRCS (Urol) suffices, and there is no need to sit any other exams. They also offer a fine mix of research opportunities and hands-on operative experience. For oncology fellowships, visit www.suonet.org. Good financial planning is crucial, especially for North American fellowships.

Jaimin Bhatt

University of Toronto Health Network, Princess Margaret Hospital, Toronto, Canada

Post-CCT SUO Fellow in Urologic Oncology. Completed his urological training in the Oxford deanery (now called Health Education Thames Valley)

Fellowships – a key ingredient or the ‘icing on the cake’?

What is the ultimate endpoint of a residency or speciality training program? Is it to complete 5 or 6 years of training in core urological procedures? Is it to produce safe, competent independent urologists? Is it to achieve FRSC (Urol) certification? In an ideal world it would be a marriage of all three; a safe, competent, independent, certified, practising urologist ready and eager to tackle any urological referral. In reality, we know that not to be the case.

Urology is a broad and advancing speciality encompassing patients of all ages and both sexes involving a complexity of benign and malignant pathologies. It is unrealistic to be an expert in all the sub-specialties and be able to offer the best and least invasive treatments to our patients. Furthermore, with a necessary emphasis on patient safety, transparency and proficiency, surgical training programs face significant barriers in affording trainees the opportunity to operate, specifically in the working time directive era.

Fellowships are usually undertaken at the completion of higher surgical training scheme often in a centre of excellence overseas. Fellowships offer trainees intensive experience in their niche area. On completion of a coveted fellowship, trainees hope to have acquired and polished the required skills to practice independently in their chosen field.

A recent pan European survey of 219 urological residents demonstrated laparoscopy and robotics were available in 74% and 17% of centres respectively [1]. Only 23% of trainees report their exposure as ‘satisfactory’. 68% have not completed a laparoscopic radical nephrectomy as first operator. Despite this 81% are considering fellowships in laparoscopy.

Buffi et al., have called for a validated and structured training curriculum in robotic surgery [2]. Trainees acknowledge the challenges in the acquisition of such skills but the modularisation of training is the best way to learn a procedure. Step by step trainees can piece together the operations. Hours spent on simulators and in dry and wet laboratories enhances these techniques. Furthermore, the dual consoles offer invaluable experience in robotics, however, are scarcely available.

The governing bodies have a responsibility to maintain standards of training as well as a duty towards patients. Proficiency in modern techniques such as laparoscopy and robotics are deficient in most training programs. Training programs need to encompass these techniques in a modular fashion from an early stage to develop the skills of tomorrows’ urologists [3]. Fellowships will undoubtedly foster and enhance these skills but a core knowledge and technical proficiency even in a simulator setting should be encouraged.

In truth, our learning and development never should never stop.

‘Live as if you were to die tomorrow. Learn as if you were to live forever’ Mahatma Gandhi

Mr Gregory Nason is a Specialist Registrar in Urology at the University Hospital Limerick, Ireland

References

- Furriel FTG, Laguna MP, Figueiredo AJ, Nunes PT, Rassweiler JJ. Training of European urology residents in laparoscopy: results of a pan-European survey. BJU Int 2013; 112: 1223–28.

- Buffi N, Van Der Poel H, Guazzoni G, Mottrie A, on behalf of the Junior European Association of Urology (EAU) Robotic Urology Section with the collaboration of the EAU Young Academic Urologists Robotic Section. Methods and Priorities of Robotic Surgery Training Program. Eur Urol 2013; epub ahead of print.

- Lee JY, Mucksavage P, Sundaram CP, McDougall EM. Best practices for robotic surgery training and credentialing. J Urol 2011; 185: 1191-7.

Thriving & Surviving As A First Year Consultant

“You never have a second chance to make a first impression.”

How you initially come across to your colleagues, the nurses and your patients as a newly appointed consultant can set the tone for your consultancy for the rest of your career. Once an opinion (winner or loser) has been formed about you, it is virtually set in stone. It is much too important to leave these things to chance. In your first year you will either sink, float or swim!

‘Thriving and Surviving as a new consultant’ [1] is a course by The Urology Foundation (TUF) specifically designed to help consultants at the start of their careers take control of situations and to become good leaders, colleagues and, most importantly, good medics. Good communication and presentation skills are vital to how others perceive and respond to you; fortunately these can be learned and developed. More importantly, leaders are not born, they can be made and it is possible to improve and hone your skills and attributes so that you can become a more confident and natural leader.

A good or natural leader always features a strong resume. a robust resume not only emphasis an excellent impression on the interviewer but also step up your confidence. the primary and most vital factor that contributes to obtaining an honest job is that the resume. Building knowledgeable resume that stands call at the gang can sometimes end up to be an intimidating, confusing and stressful task. But, with the advancement in technology building knowledgeable resume has become quite easy.

The resume builder online is one such innovation that has made professional resume building easy, efficient and fewer stressful. The professional resume builder saves tons of quality time which may be utilized for other purposes like gaining education or developing skills. you only got to fill within the details within the appropriate fields mentioned within the resume template online and knowledgeable resume is produced in minutes.

Last weekend, a number of newly, or about to be appointed, consultants attended an interactive two-day course in Leeds where subjects such as team building and development were discussed. “The team” was considered to be the colleagues, managers, nurses and other healthcare professionals involved in the urological care of patients. We discussed and debated how we could create the “Manchester United” department of urology, delivering the best possible in patient treatment and care.

A new consultant shouldn’t try to change too much at first, but instead carefully assess and evaluate the lie of the land. Learning about the department, associated departments and the hospital itself takes time and trouble. It is good though to have at least five SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic and Time-constrained) goals to be achieved within the first year of his or her appointment. But what should these be? Do let us know.

The medical defence organisations recognise that the first year of a consultant’s career is one of exceptionally high risk for complaints and litigation. We focused therefore on avoiding pitfalls, dealing with complications, and responding to complaints and serious untoward incidents (SUOs).

Navigating your way though the dangerous waters of your first year as a consultant can be a very tricky business. We would love to hear about your experiences in that situation, or, if you attended the course, what you thought of it and how we could do it better.

Roger Kirby, The Prostate Centre, London

Louise de Winter, Chief Executive, The Urology Foundation

[1] The course was made possible by an Educational Grant from Takeda UK Ltd. Takeda had no involvement in the content of organisation of the meeting.

Comments on this blog are now closed.

Article of the week: Centralized simulation training combines technical and non-technical skills

Every week the Editor-in-Chief selects the Article of the Week from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to the article itself, there is an accompanying editorial written by a prominent member of the urological community. This blog is intended to provoke comment and discussion and we invite you to use the comment tools at the bottom of each post to join the conversation.

If you only have time to read one article this week, it should be this one.

Development and implementation of centralized simulation training: evaluation of feasibility, acceptability and construct validity

Mohammad Shamim Khan, Kamran Ahmed, Andrea Gavazzi, Rishma Gohil, Libby Thomas*, Johan Poulsen†, Munir Ahmed, Peter Jaye* and Prokar Dasgupta

MRC Centre for Transplantation, King’s College London, King’s Health Partners, Department of Urology, Guy’s Hospital , *Simulation and Interactive Learning (SaIL) Centre, Guy’s & St Thomas NHS Foundation Trust , and †Department of Urology, Aalborg Denmark and King’s College Hospital, London, UK

OBJECTIVES

• To establish the feasibility and acceptability of a centralized, simulation-based training-programme.

• Simulation is increasingly establishing its role in urological training, with two areas that are relevant to urologists: (i) technical skills and (ii) non-technical skills.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

• For this London Deanery supported pilot Simulation and Technology enhanced Learning Initiative (STeLI) project, we developed a structured multimodal simulation training programme.

• The programme incorporated: (i) technical skills training using virtual-reality simulators (Uro-mentor and Perc-mentor [Symbionix, Cleveland, OH, USA] , Procedicus MIST-Nephrectomy [Mentice, Gothenburg, Sweden] and SEP Robotic simulator [Sim Surgery, Oslo, Norway]); bench-top models (synthetic models for cystocopy, transurethral resection of the prostate, transurethral resection of bladder tumour, ureteroscopy); and a European (Aalborg, Denmark) wet-lab training facility; as well as (ii) non-technical skills/crisis resource management (CRM), using SimMan (Laerdal Medical Ltd, Orpington, UK) to teach team-working, decision-making and communication skills.

• The feasibility, acceptability and construct validity of these training modules were assessed using validated questionnaires, as well as global and procedure/task-specific rating scales.

RESULTS

• In total 33, three specialist registrars of different grades and five urological nurses participated in the present study.

• Construct-validity between junior and senior trainees was signifi cant. Of the participants, 90% rated the training models as being realistic and easy to use.

• In total 95% of the participants recommended the use of simulation during surgical training, 95% approved the format of the teaching by the faculty and 90% rated the sessions as well organized.

• A significant number of trainees (60%) would like to have easy access to a simulation facility to allow more practice and enhancement of their skills.

CONCLUSIONS

• A centralized simulation programme that provides training in both technical and non-technical skills is feasible.

• It is expected to improve the performance of future surgeons in a simulated environment and thus improve patient safety.