Adult-type testicular granulosa cell tumor: a case report and radiological findings of a rare testicular tumor

We report a case of an adult-type testicular granulosa cell tumor and the radiological findings of this rare tumor.

Authors: Kobayashi, Ko; Itoh, Naoki; Sakai, Shigeru; Sato, Masaaki

Corresponding Author: Kobayashi, Ko

Abstract

Among testicular neoplasms, adult-type testicular granulosa cell tumors are quite rare. We report a case of an adult-type testicular granulosa cell tumor and the radiological findings of this rare tumor. The patient was a 49-year-old man with a mass on the left testis that grew slowly for 5 years. An ultrasound scan of the left testis showed a hypoechoic and well-circumscribed mass within the normal testicular parenchyma. A computer tomographic (CT) scan of the whole abdomen revealed the mass to be mildly ring-enhanced in the left testis after contrast administration. We performed left radical orchiectomy. The pathological findings of the surgical specimen showed that the tumor was consistent with an adult-type granulosa cell tumor. The patient has no evidence of disease after 24 months of follow-up.

Introduction

Sex cord-stromal tumors account for only about 4% of testicular neoplasms [1]. Among such tumors, the adult-type testicular granulosa cell tumor is quite rare [1-3]. Therefore, radiological findings of this uncommon tumor have rarely been reported. We report a case of an adult-type testicular granulosa cell tumor including the radiological findings.

Case report

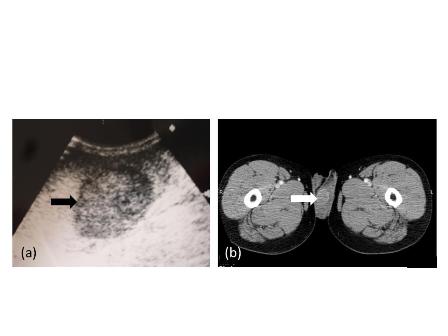

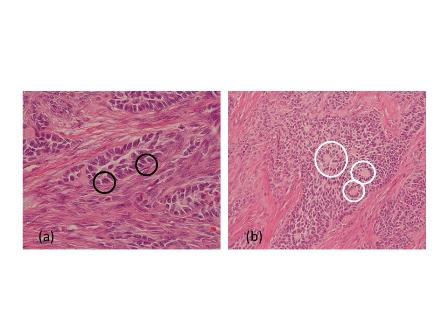

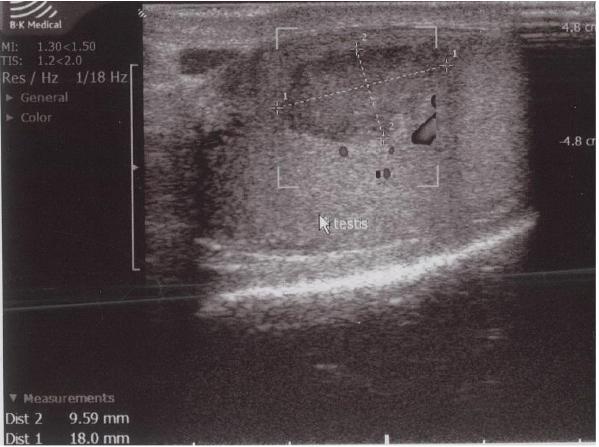

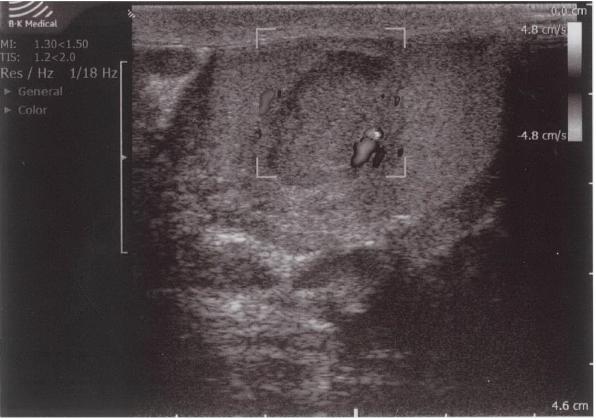

A 49-year-old man with a mass of the left testis that had grown slowly for 5 years visited our office in November 2009. We found a hard solid mass of his left testis on physical examination. An ultrasound scan of the left testis showed a hypoechoic and well-circumscribed mass within the normal testicular parenchyma (Figure 1a). A computer tomographic (CT) scan of the whole abdomen revealed the mass to be mildly ring-enhanced in the left testis after contrast-agent administration (Figure 1b). There were no enlarged lymph nodes or abnormalities in other organs in the CT findings. Tumor markers such as alpha-fetoprotein and human chorionic gonadotropin were within normal ranges. We diagnosed his scrotal mass as testicular tumor and performed left radical orchiectomy. The cut surface of the orchiectomy specimen displayed a solid, hard and white tumor occupying part of the testicular parenchyma. The size of the tumor was 2.6×2.5×2.0 cm. Microscopically, tumor cells had grooved nuclei (coffee-bean nuclei) and formed microfollicular, macrofollicular and trabecular patterns (Figure 2a). In the follicles, Call-Exner-like bodies were focally seen (Figure 2b). Immunostaining tests were positive for vimentin, CD99 and alpha-inhibin. These pathological findings showed that the tumor was consistent with an adult-type granulosa cell tumor. The patient has no evidence of disease after 24 months of follow-up.

Discussion

Granulosa cell tumors are classified under the category of sex-cord stromal tumors. Sex-cord stromal tumors account for only 4% of testicular neoplasms [1]. Granulosa cell tumors of the testis are morphologically similar to their ovarian counterparts. Two variants are distinguished, the adult and juvenile types [1-3]. Granulosa cell tumors of the ovary account for less than 5% of all malignant tumors but represent the most common malignant sex-cord stromal tumor of the ovary [4]. On the other hand, adult-type testicular granulosa cell tumors are quite rare [1-3,5].

Adult-type testicular granulosa cell tumors are mostly benign; however, malignant behavior is a possibility [1,2,5]. In a previous report, there was a case that metastasized to bone, presenting 6 years after orchiectomy [6]. Therefore we should perform long-term follow-up for our case.

In a previous case report, an ultrasound scan of a juvenile-type testicular granulosa cell tumor showed a well-defined multicystic intratesticular solid mass [7]. The present adult-type case was different in that it was hypoechoic and there was a well-circumscribed mass within the normal testicular parenchyma. Another report also showed a hypoechoic mass on the ultrasound scan of a patient with an adult-type testicular granulosa cell tumor [8]. Thus, these two variants had different findings on ultrasound scans. However, differential diagnosis of the classification of testicular neoplasms is difficult using only ultrasound scanning because approximately 80% of testicular neoplasms have a hypoechoic appearance on ultrasound scans [9].

Here we reported CT findings of a testicular tumor diagnosed as an adult-type granulosa cell tumor. To our knowledge, the current report is the third one with CT findings of the primary site of this quite rare testicular tumor. In the previous cases, there was one report of a mildly enhanced heterogenous soft tissue mass involving the testis and another with an enhanced mass in the scrotum on the CT scan [10-11]. Granulosa cell tumors of the ovary show a spectrum of imaging manifestations due to their various histologic appearances and arrangements of tumor cells [4]. Although the findings for this rare tumor on CT scans were slightly different in the three reports, it is unknown at this stage whether adult-type testicular granulosa cell tumors also present such a spectrum of imaging manifestations. We believe that accumulating knowledge from radiological findings on this rare testicular tumor will be useful for diagnosis of the disease in the future.

Figure 1. Radiological findings.

(a) Ultrasound scan of the left testis. The black arrow indicates a hypoechoic and well-circumscribed mass within the normal testicular parenchyma.

(b) A computer tomographic scan shows a mass (white arrow) that is mildly ring-enhanced in the left testis after contrast-medium administration.

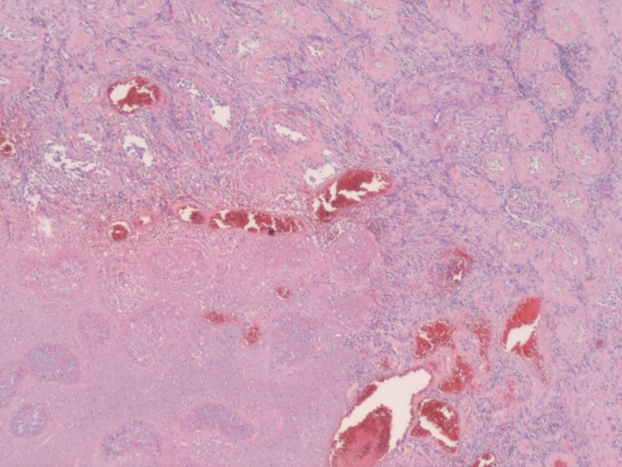

Figure 2. Pathological findings.

(a) Black circles indicate tumor cells with grooved nuclei (coffee-bean nuclei).

(b) White circles indicate Call-Exner-like bodies.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

1. Ulbright TM. Neoplasms of the testis. In: Bostwick DG, Eble JN (eds). Urologic Surgical Pathology. Mosby, St. Louis, 1997; 567-646.

2. Eble JN, Sauter G, Epstein JI, Sesterhenn IA. Pathology and Genetics of Tumors of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs. IARCPress, Lyon, 2004.

3. Ulbright TM, Amin MB, Young RH. Tumors of the Testis, Adnexa, Spermatic Cord, and Scrotum. American Registry of Pathology, Washington, D.C.,1999.

4. Jung SE, Rha SE, Lee JM et al. CT and MRI findings of sex cord-stromal tumor of the ovary. Am J Roentgenol. 2005; 185: 207-15.

5. Hammerich KH, Hille S, Ayala GE et al. Malignant advanced granulosa cell tumor of the adult testis: case report and review of the literature. Hum Pathol. 2008; 39:701-5.

6. Suppiah A, Musa MM, Morgan DR, North AD. Adult granulosa cell tumor of the testis and bony metastasis. A report of the first case of granulosa cell tumor of the testicle metastasising to bone. Urol Int. 2005; 75:91-3.

7. Lin KH, Lin SE, Lee LM. Juvenile granulosa cell tumor of adult testis: a case report. Urology. 2008; 72: 230.e11-3.

8. Guzzo T, Gerstein M, Mydlo JH. Granulosa cell tumor of the contralateral testis in a man with a history of cryptorchism. Urol Int. 2004; 72:85-7.

9. Heiken JP. Tumors of the testis and testicular adnexa. In: Pollack HM, McClennan BL (eds). Clinical Urography. W.B. Saunders Company, Philadelphia, 2000; 1716-1742.

10. Gupta A, Mathur SK, Reddy CP, Arora B. Testicular granulosa cell tumor, adult type. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2008; 51: 405-6.

11. Song Z, Vaughn DJ, Bing Z. Adult type granulosa cell tumor in adult testis: report of a case and review of the literature. Rare Tumors. 2011; 3: e37.

Date added to bjui.org: 11/02/2013

DOI: 10.1002/BJUIw-2012-073-web