Article of the Week: Multiple Growth Periods of SRMs Predict Unfavourable Pathology

Every Week, the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Week from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to the article itself, there is an accompanying editorial written by a prominent member of the urological community. This blog is intended to provoke comment and discussion and we invite you to use the comment tools at the bottom of each post to join the conversation.

Finally, the third post under the Article of the Week heading on the homepage will consist of additional material or media. This week we feature a video discussing the paper.

If you only have time to read one article this week, it should be this one.

Multiple growth periods predict unfavourable pathology in patients with small renal masses

Abstract

Objective

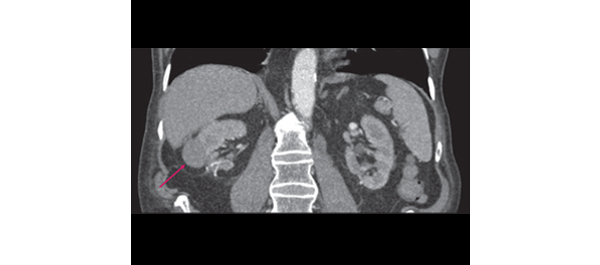

To use the number of positive growth periods as a characterization of the growth of small renal masses in order to determine potential predictors of malignancy.

Patients and Methods

Patients who underwent axial imaging at multiple time points prior to surgical resection for a small renal mass were queried. Patients were categorized based on their pathological tumour grade and stage: favourable (benign, chromophobe and low‐grade pT1–2 renal cell carcinoma [RCC]) vs unfavourable (high‐grade of any stage and low‐grade pT3–4 RCC). A positive growth period was counted each time the difference in greatest tumour diameters between two images was positive. The Cochran–Armitage trend test and Somers’ D association were used to determine if the number of positive growth periods was correlated with unfavourable pathology.

Results

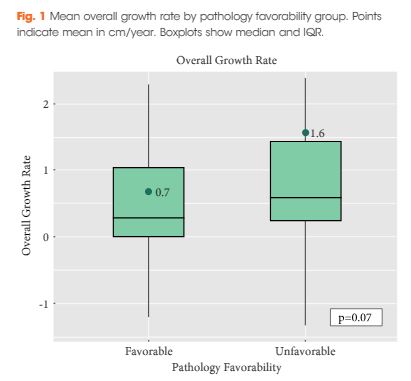

Of the 124 patients, 86 (69.4%) had favourable pathology and 38 (30.6%) had unfavourable pathology. Those who had favourable pathology were younger than those who had unfavourable pathology: median (interquartile range [IQR]) 61.0 (52.2–66.0) vs 68.5 (61.5–77.0); P < 0.001. The overall growth rate was higher in the unfavourable group, but was not statistically significant: mean (sd) 0.7 (1.7) vs 1.6 (2.8) cm/year; P = 0.07. There was a significant trend difference in the number of positive growth periods between favourability groups (P = 0.02). An association between increased number of positive growth periods and unfavourable pathology was observed: 0.15 (95% confidence interval 0.02, 0.29). The ratios of favourable to unfavourable pathology were 1.8, 1.0, 0.66, 0.59 and 0 as the number of positive growth periods increased from 0 to 4, respectively.

Conclusion

While overall growth rate was not predictive of pathology favourability, there was a positive association between the number of positive growth periods and unfavourable pathology. The number of positive growth periods may be a potential parameter for malignant potential in patients undergoing active surveillance for small renal masses.