Urology in Zomba, Malawi. Reflecting on surgical care in a Resource-Limited country

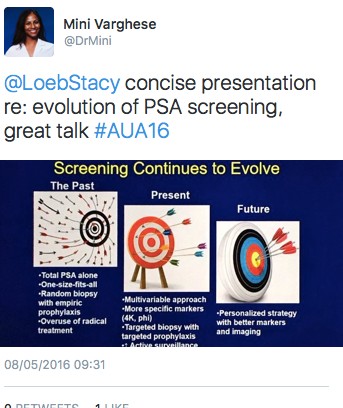

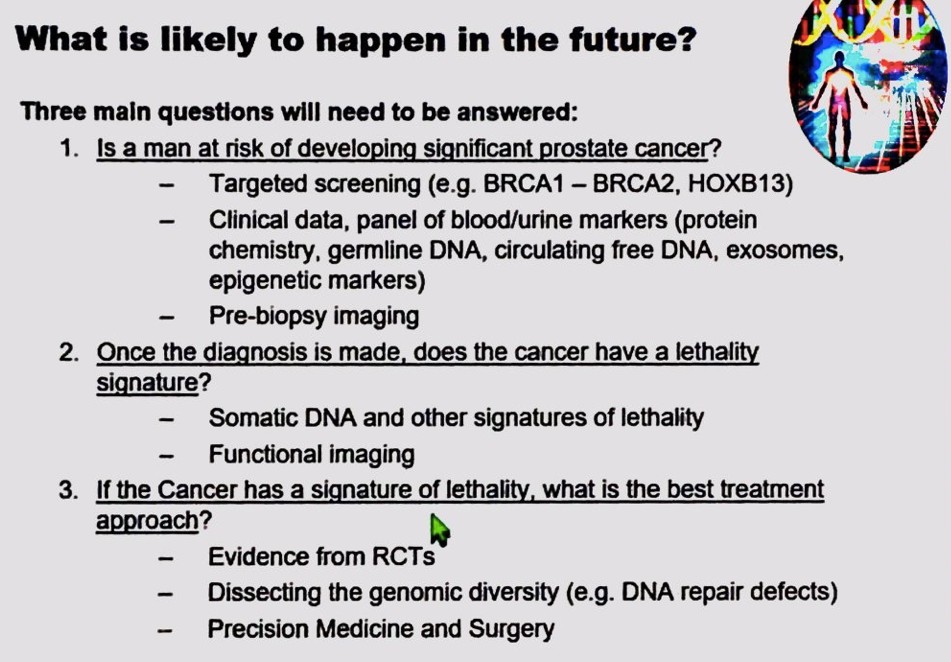

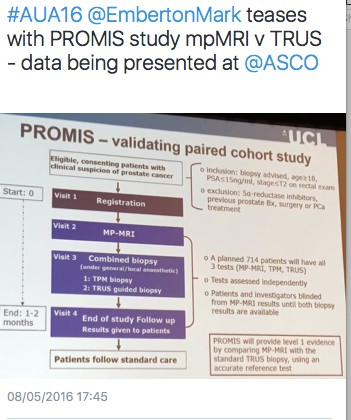

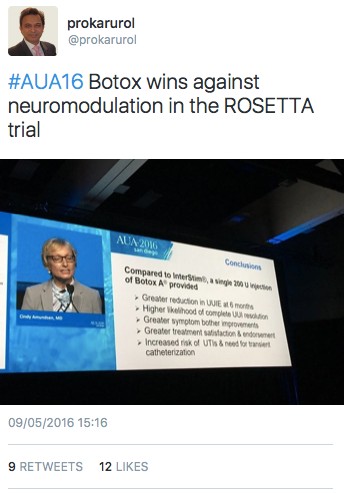

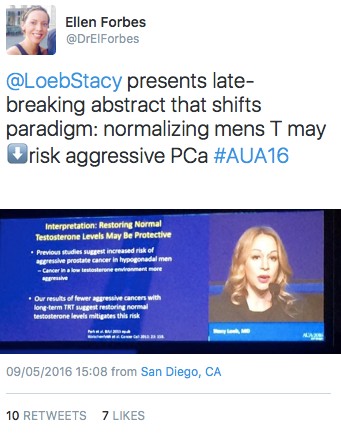

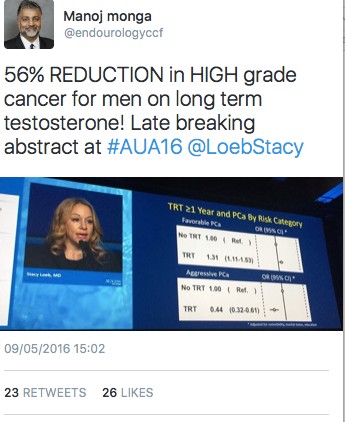

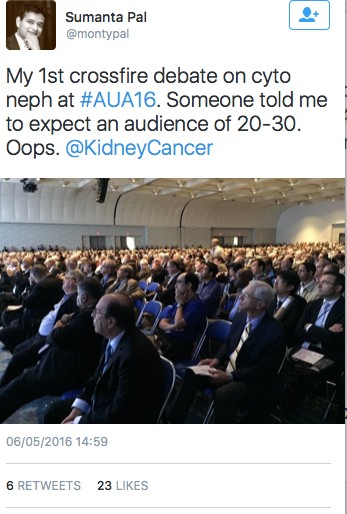

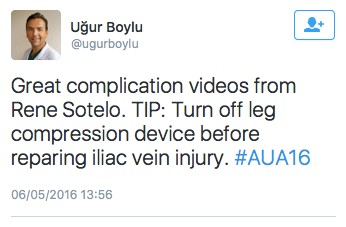

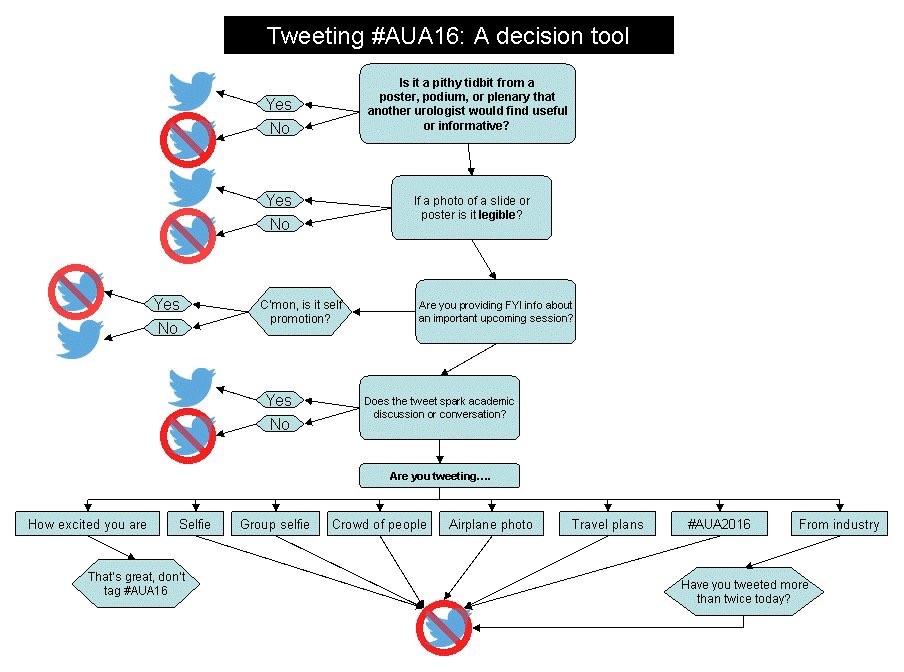

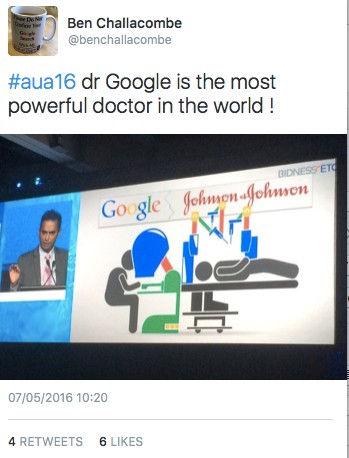

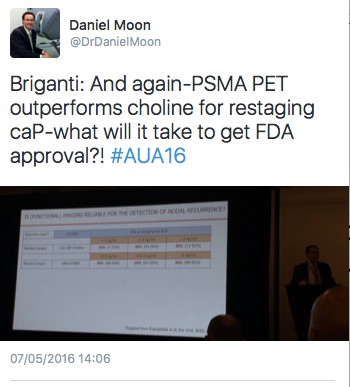

At the recent AUA meeting in San Diego as at all of our major meetings, a tremendous amount of data was presented and technology displayed to advance our specialty. Walking through exhibit hall one sees an expensive bauble at every turn. The advancement of urology over the last 50 years has been remarkable. We have a lot to be proud of. I think we have the most interesting, exciting specially in all of medicine. Urologist are generally technophiles and have always loved to push surgical procedures to new heights. From robotics, lasers and endourology to advancing the molecular understanding of disease, urologists have always aimed to drive the bus.

At the recent AUA meeting in San Diego as at all of our major meetings, a tremendous amount of data was presented and technology displayed to advance our specialty. Walking through exhibit hall one sees an expensive bauble at every turn. The advancement of urology over the last 50 years has been remarkable. We have a lot to be proud of. I think we have the most interesting, exciting specially in all of medicine. Urologist are generally technophiles and have always loved to push surgical procedures to new heights. From robotics, lasers and endourology to advancing the molecular understanding of disease, urologists have always aimed to drive the bus.

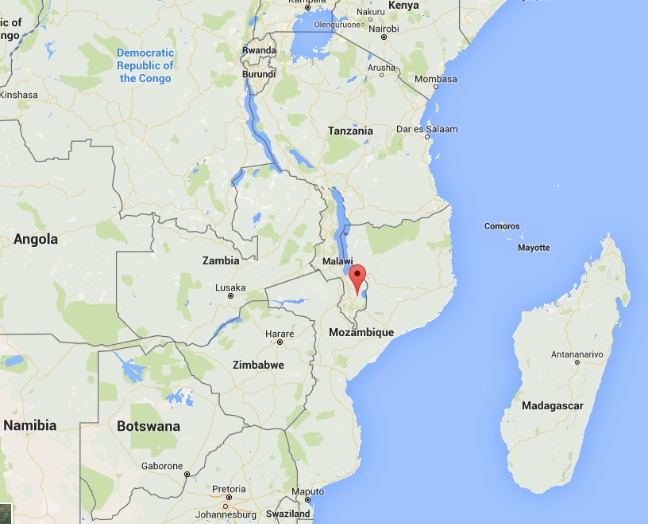

As many of you know, I am on a short trip to Malawi Africa. I have written about this elsewhere. I am here on one hand as a board member for Dignitas International. On the surgical side it is not a mission under the guise of anyone but rather my own personal attempt to understand what urology and surgery in a resource poor country might look like. I have been here in Zomba, Malawi and working at Zomba Central Hospital, which is one of four central hospitals in the country.

A goal has been to try and assess what the basic urological needs might be in this part of the world and see how I could help bridge the gap, whether it would be with equipment, external manpower or ultimately by improving training and leaving something sustainable. I optimistically set out, confident in my abilities to eventually network and bring colleagues together and establish over time a reasonable urology program that at least resembles something familiar. I have the COSECSA guidelines on what it takes to establish a training program at my side. Perhaps nothing illustrates what a daunting task this will be like my days in surgery this week.

To start with, a typical OR at ZCH requires some refocusing compared to what I am used to. My DaVinci robot is nowhere to be seen

I made ward rounds with my clinical officer yesterday and lined up several TUR type cases to try and do, with men bleeding from bladder tumours (all invariably Bilharzial disease) as well as men in retention. Some have had catheters for months, even years.

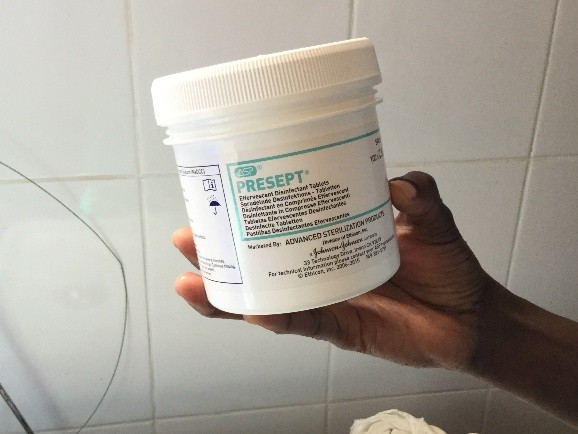

First there is the set up. No discussion about lasers and lifts or any other such fun. We don’t even have the 3L irrigation bags. For my irrigation set up, with a little water and some chlorine pucks we are ready to go.

My first patient was a TURBT. A very large, incompletely resected lesion, actively bleeding. I clearly left disease behind but perhaps he won’t bleed for a while. The tissue will not be sent to pathology. Patients need to pay 16,000 MWK for it. The typical pay for many is 20,000-30000/month and 1$USD=700 MWK. Managing him from any even rudimentary oncological perspective is a non-starter.

The second patient also had a bladder tumour. It was palpable as a mass to just under the skin. Again, the goal was to stop some bleeding, at least for a few weeks. He almost certainly has metastatic disease but I have no way to image and know for sure. I did order a chest xray to look for obvious pulmonary nodules. He will eventually just quietly die.

Before I could start a third case I found myself in the gynecology OR 2 weeks after a hysterectomy post-delivery for bleeding. Following an injury, the left ureter was leaking. I attempted the repair as best as I could with no proper light, no electrocautery no retractors and no ability to stent my freshly re-implanted ureter. All of this on an HIV+ve new mother. I hope it heals open. I am not sure if it will. I have come to understand that ureteral injuries are a not uncommon consequence of obstetrical care in Malawi.

My third patient had a TURP which was fairly straightforward. He should hopefully void assuming reasonable residual bladder function. He has had a catheter in place for months.

At least we did do some work Thursday. On Tuesday my four patient list turned into one as my anesthetist did not attend. Before surgical care can be improved, the critical shortage of anesthesia care has to also be addressed. I also wrote about that earlier.

I did bring a surgery checklist to ZCH on Tuesday.

And Thursday in follow up, I gave a talk to the surgical team about checklists and so that is certainly good.

They keep asking me to see men in the clinic with catheters. With the inefficiencies of late start times, anesthesia shortages and only a week to go, most will get left behind. It is really a depressing thought.

My OR team though is there to help and keen to learn.

Daniel, Rex (T Rex) and Maryeuster

As I reflect on my experience in the operating room during week one I am struck by how discordant what I saw in San Diego was from the realities still faced in much of the world. Basic endoscopic equipment does not exist. Serendipitously, a retired colleague of mine did bring some basic equipment a few months ago and this one set, washed and then resterilized (in a pail of chlorinated water) is all that we have. I am still not clear what happens when the loops wear out.

I do question when we pull millions of dollars and much intellectual capital into improving technology and chasing robots as to what are we really doing to benefit the care of our urological patients on a global scale. Do we have some obligation as champions of mens’ health and urologic care more broadly, to play a part? I do wonder whether some of our intellectual energy and financial resources could be better spent simply bringing parts of this world even into the 1970s. If this was valued as worthy of academic support and promotion the way oncology, endourology and everything else is in our specialty is, then some of the bright young minds in our field might move this along further. Whether we do a robot prostatectomy retroperitoneally or intraperitoneally, debate about a Rocco stitch or tweak this or do that, these changes are often incremental at best. Supine versus prone PCNL? Who cares. Other parts of the world I think deserve some of our high-level expertise to meet their complex challenges. I would invite the urological community to try and collectively address this problem. Should we keep pouring all of our massive resources only to steady, incremental benefit? Clearly we always must advance the body of knowledge and the state of the art. However, is there a role for reserving some resource and energy to advocate for simpler things that could affect a change on the order of several magnitudes? Some of the easier things we might do is to at least act as advocates and lead some process change whether it be a surgical checklist, counting instruments and sutures pre and post operatively and ensure better preoperative screening and post-operative care. Updating equipment and building surgical expertise necessarily follows.

Laser TURP? Plasma button? Urolift? The men in Malawi and much of Africa would be happy just to get rid of their catheters.

We often joke about our ‘first world problems’. It’s time to get serious.

Let’s do better.

Dr Rajiv Singal is a Urologist at Michael Garron Hospital and an Assistant Professor in the Department of Surgery at the University of Toronto

Follow him on Twitter at @DrRKSingal

To read more about Dr Singal’s experience in Malawi follow this link https://www.rajivsingal.com/blogCategories/view/malawi-june-2016/