Article of the Week: Impact of warm ischaemia time on postoperative renal function after partial nephrectomy for clinical T1 renal cell carcinoma

Every Week the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Week from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to the article itself, there is an accompanying editorial written by a prominent member of the urological community. This blog is intended to provoke comment and discussion and we invite you to use the comment tools at the bottom of each post to join the conversation.

If you only have time to read one article this week, it should be this one.

Impact of warm ischaemia time on postoperative renal function after partial nephrectomy for clinical T1 renal cell carcinoma: a propensity score-matched study

Objectives

To analyse the effect of prolonged warm ischaemia time (WIT) on long-term renal function after partial nephrectomy (PN), as controversy still exists as to whether prolonged WIT adversely affects the incidence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) after PN.

Patients and Methods

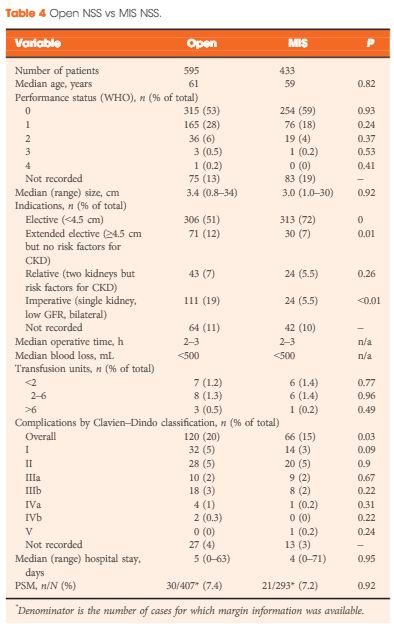

We reviewed data from 1816 patients who underwent PN for a clinical T1 renal tumour. The propensity scores for prolonged WIT were calculated with the shorter WIT group (<30 min) matched to the longer WIT group (≥30 min) in a 2:1 ratio. Multivariate analysis was used to determine independent predictors for occurrence of postoperative CKD [defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of <60 mL/min/1.73 m2] and major renal function deterioration (MRFD; defined as an eGFR decrease of ≥25% postoperatively).

Results

After propensity score matching, there was no significant difference in CKD-free survival between the two WIT groups (P = 0.787). Furthermore, longer WIT did not show any significant associations with postoperative CKD-free survival [hazard ratio (HR) 1.002, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.989–1.015; P = 0.765) and MRFD-free survival (HR 1.014, 95% CI 1.000–1.028; P = 0.055). From further subgroup analyses using more specific WIT thresholds (≤20, 21–30, 31–40, 41–50, ≥50 min) and status of preoperative CKD, no significant differences were noted in CKD and MRFD-free survival amongst the subgroups (all P > 0.05).

Conclusions

Prolonged WIT was not associated with increased incidence of CKD or MRFD after PN.