Posts

Article of the week: Ultrasound guidance can be used safely for renal tract dilatation during percutaneous nephrolithotomy

Every week, the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Week from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to the article itself, there is an editorial written by a prominent member of the urological community and a visual abstract prepared by a trainee urologist; we invite you to use the comment tools at the bottom of each post to join the conversation.

If you only have time to read one article this week, we recommend this one.

Ultrasound guidance can be used safely for renal tract dilatation during percutaneous nephrolithotomy

Manuel Armas-Phan*, David T. Tzou*†, David B. Bayne*, Scott V. Wiener*, Marshall L. Stoller* and Thomas Chi*

*Department of Urology, University of California, San Francisco, CA and †Division of Urology, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA

Abstract

Objectives

To compare clinical outcomes in patients who underwent percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) with renal tract dilatation performed under fluoroscopic guidance vs renal tract dilatation with ultrasound guidance.

Patients and Methods

We conducted a prospective observational cohort study, enrolling successive patients undergoing PCNL between July 2015 and March 2018. Included in this retrospective analysis were cases where the renal puncture was successfully obtained with ultrasound guidance. Cases were then grouped according to whether fluoroscopy was used to guide renal tract dilatation or not. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 15.1 including univariate (Fisher’s exact test, Welch’s t‐test) and multivariate analyses (binomial logistic regression, ordinal logistic regression, and linear regression).

Results

A total of 176 patients underwent PCNL with successful ultrasonography‐guided renal puncture, of whom 38 and 138 underwent renal tract dilatation with fluoroscopic vs ultrasound guidance, respectively. There were no statistically significant differences in patient age, gender, body mass index (BMI), preoperative hydronephrosis, stone burden, procedure laterality, number of dilated tracts, and calyceal puncture location between the two groups. Among ultrasound tract dilatations, a higher proportion of patients were placed in the modified dorsal lithotomy position as opposed to prone, and a significantly shorter operating time was observed. Only modified dorsal lithotomy position remained statistically significant after multivariate regression. There were no statistically significant differences in postoperative stone clearance, complication rate, or intra‐operative estimated blood loss. A 5‐unit increase in a patient’s BMI was associated with 30% greater odds of increasingly severe Clavien–Dindo complications. A 5‐mm decrease in the preoperative stone burden was associated with 20% greater odds of stone‐free status. No variables predicted estimated blood loss with statistical significance.

Conclusions

Renal tract dilatation can be safely performed in the absence of fluoroscopic guidance. Compared to using fluoroscopy, the present study demonstrated that ultrasonography‐guided dilatations can be safely performed without higher complication or bleeding rates. This can be done using a variety of surgical positions, and future studies centred on improving dilatation techniques could be of impactful clinical value.

Editorial: Zero‐radiation stone treatment

In this month’s BJUI, Armas‐Phan et al. [1] report on a prospective observational trial of fluoroscopic vs ultrasound (US)‐guided tract dilatation during percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL). A total of 176 patients underwent successful initial US‐only guided puncture; of these patients, 138 had US‐only dilatation, while in 38 fluoroscopy was required. The authors found no difference in patient factors (e.g. age, gender, body mass index [BMI]) or stone factors (hydronephrosis, stone burden, number of tracts or puncture location). On multivariate analysis, US dilatation was more likely to be performed in the modified dorsal lithotomy position (compared to prone), but there was no significant difference in important outcomes such as stone clearance, complication rates or blood loss.

Whilst only reporting on access (and not necessarily dilatation), the Clinical Research Office of the Endourological Society PCNL Global Study shows us that worldwide fluoroscopic access is by far the most common (88.3% of cases) [2] and there are relatively few reports of US‐guided dilatation in the literature. The technique does produce technical challenges as the surgeon needs to confidently identify the depth of the dilators or balloon and be sure of its location relative to calyceal anatomy. Whilst dilating short is not usually a problem as simply re‐dilating can be done, dilating too far carries serious risk of perforation of the pelvicalyceal system and vascular injury. The authors’ described technique does rely on good kidney and guidewire visualisation, and if this is not possible then fluoroscopy is used instead. Thus, even in this series with experts at this technique, 38 (22%) underwent fluoroscopic dilatation after US‐guided puncture, and of the 138 with intended US dilatation, seven (5%) were converted to fluoroscopy. Furthermore, 115 patients never entered this series as they underwent initial fluoroscopic‐guided puncture. Thus, it is important to realise that this is a series of select patients being treated by expert enthusiasts of this technique and fluoroscopy should be available in the operating theatre, as it is not possible to do this technique for all patients. In particular, obesity limits the visualisation under US and the authors have previously shown that renal access drops from 76.9% of normal‐weight patients (BMI <25 kg/m2) to 45.6% for those classified as obese (BMI >30 kg/m2) [3]. An alternative strategy to avoid radiation is to use endoscopic combined intrarenal surgery (ECIRS), as the depth of dilatation can be monitored by direct visualisation via the flexible ureteroscope.

Patients and healthcare professionals are increasingly aware of the risks posed by ionising radiation. Ferrandino et al. [4] analysed radiation exposure of patients presenting with acute stone episodes in an American setting. The mean dose was a staggering 29.7 mSv and 20% of patients received >50 mSV. There is also awareness of risk to the operating staff from endourological procedures and although doses are relatively low [5], these can accumulate during a lifetime of operating, with risks of not only malignancy but also cataract formation [6]. Whilst I am sure we all wear protective lead gowns in the operating theatre, how many people wear lead glasses? A recent study showed that, at typical workload, the annual dose to the lens of the eye was 29 mSv in interventional endourology [7].

As urologists, we should all be aware of these risks and follow the ALARA (As Low As Reasonably Achievable) principals of keeping doses to a minimum. Thus, this paper [1] is particularly welcome and shows zero‐radiation procedures can be safely performed. The authors now attempt this technique for all PCNL procedures and achieve US‐only puncture and dilatation in over half of their patients. Hopefully, this paper will inspire us all to look at reducing or eliminating radiation usage in our stone procedures and this will be good for patients and surgeons alike.

by Matt Bultitude

References

- , , et al. Ultrasound guidance can be used safely for renal tract dilatation during percutaneous nephrolithotomy. BJUI 2019; 125: 284-91

- , , et al. The Clinical Research Office of the Endourological Society Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy Global Study: indications, complications, and outcomes in 5803 patients. J Endourol 2011; 25: 11– 7

- , , , , . Ultrasound guidance to assist percutaneous nephrolithotomy reduces radiation exposure in obese patients. Urology 2016; 98: 32– 8

- , , et al. Radiation exposure in the acute and short‐term management of urolithiasis at 2 academic centers. J Urol 2009; 181: 668– 72

- , , et al. Surgical staff radiation protection during fluoroscopy‐guided urologic interventions. J Endourol 2016; 30: 638– 43

- , , et al. Risk of radiation‐induced cataracts: investigation of radiation exposure to the eye lens during endourologic procedures. J Endourol 2018; 32: 897– 903

- , , et al. Risk of radiation exposure to medical staff involved in interventional endourology. Radiat Prot Dosimetry 2015; 165: 268– 71

Video: Stereotactic ablative body radiotherapy for inoperable primary kidney cancer

Stereotactic ablative body radiotherapy for inoperable primary kidney cancer

Abstract

Objective

To assess the feasibility and safety of stereotactic ablative body radiotherapy (SABR) for renal cell carcinoma (RCC) in patients unsuitable for surgery. Secondary objectives were to assess oncological and functional outcomes.

Materials and Methods

This was a prospective interventional clinical trial with institutional ethics board approval. Inoperable patients were enrolled, after multidisciplinary consensus, for intervention with informed consent. Tumour response was defined using Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors v1.1. Toxicities were recorded using Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v4.0. Time-to-event outcomes were described using the Kaplan–Meier method, and associations of baseline variables with tumour shrinkage was assessed using linear regression. Patients received either single fraction of 26 Gy or three fractions of 14 Gy, dependent on tumour size.

Results

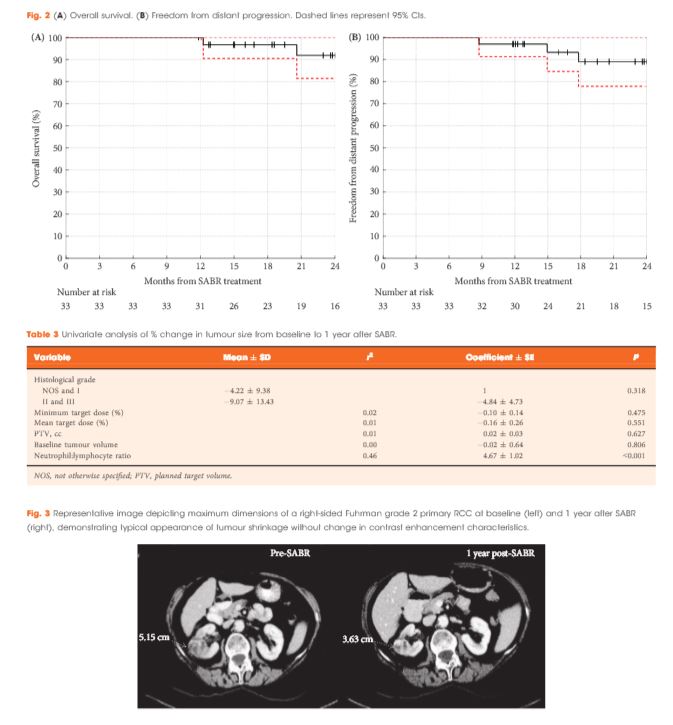

Of 37 patients (median age 78 years), 62% had T1b, 35% had T1a and 3% had T2a disease. One patient presented with bilateral primaries. Histology was confirmed in 92%. In total, 33 patients and 34 kidneys received all prescribed SABR fractions (89% feasibility). The median follow-up was 24 months. Treatment-related grade 1–2 toxicities occurred in 26 patients (78%) and grade 3 toxicity in one patient (3%). No grade 4–5 toxicities were recorded and six patients (18%) reported no toxicity. Freedom from local progression, distant progression and overall survival rates at 2 years were 100%, 89% and 92%, respectively. The mean baseline glomerular filtration rate was 55 mL/min, which decreased to 44 mL/min at 1 and 2 years (P < 0.001). Neutrophil:lymphocyte ratio correlated to % change in tumour size at 1 year, r2 = 0.45 (P < 0.001).

Conclusion

The study results show that SABR for primary RCC was feasible and well tolerated. We observed encouraging cancer control, functional preservation and early survival outcomes in an inoperable cohort. Baseline neutrophil:lymphocyte ratio may be predictive of immune-mediated response and warrants further investigation.

Editorial: Stereotactic radiotherapy for primary renal cell carcinoma: time for larger-scale prospective studies

A number of important trends in kidney cancer diagnosis have emerged in recent decades, including the increasing detection of renal tumours in older patients with more comorbidities. In the UK in 2012–2014, 50% of new cases were diagnosed in people aged 70 years and over. Whilst many of these lesions are incidental small renal masses suitable for active surveillance, the dilemma of how to manage the higher-risk lesion (rapid growth kinetics, larger size, symptomatic lesion) is increasingly encountered. Surgical management may pose an unacceptable risk of morbidity, mortality or dialysis, yet these patients may live long enough to experience the consequences of disease progression. Thermal ablation is an option for small cortical tumours (≤3 cm), but there are limitations for larger or centrally located tumours.

In this issue of BJUI, Siva and colleagues [1] report promising early efficacy and toxicity data using stereotactic ablative body radiotherapy (SABR) for the treatment of primary RCC in this difficult cohort. SABR is a non-invasive treatment that delivers very high doses of radiation over one to five outpatient sessions. It uses advanced motion management, radiation planning and image guidance techniques to ensure delivery of an ablative dose with millimetre precision. Survival benefits with stereotactic radiosurgery have been demonstrated in patients with solitary brain metastases [2], and SABR is now an accepted standard of care for patients with medically inoperable early-stage lung cancer [3]. Randomized phase III trials are currently under way, testing SABR against standard of care in primary prostate (clinicaltrials.gov ID NCT01584258) and liver cancer (NCT01730937) and in the oligometastatic setting (NCT02759783). Historically considered radio-resistant, both pre-clinical and clinical data now support the sensitivity of RCC to high-dose per fraction radiotherapy, as used in SABR [4].

The study by Siva and colleagues is one of the largest, early-phase, prospective studies of SABR for primary RCC to date, accruing 37 patients with cT1a–cT2a RCC not suitable for other therapies. Importantly, this was not a cohort of incidentally detected small renal masses. The majority (65%) of tumours were >4 cm (median 4.8 cm), were growing on surveillance or symptomatic, and were biopsy-proven. The inclusion of enlarging T1a tumours is not unreasonable. A recent analysis of patients with localized T1a kidney cancer from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Medicare data reported an excess of kidney cancer deaths for non-surgically managed patients aged >75 years, highlighting how difficult it can be to find the right balance between active and expectant management in this group [5]. Indeed 11% of patients in the present study by Siva et al. developed distant metastases by 2 years.

In the present study, tumours <5 cm received a single 26-Gy fraction of SABR, whilst tumours >5 cm received 42 Gy over three fractions. Whilst acknowledging a number of uncertainties in modelling, this should equate to an equivalent biological dose in excess of 100 Gy. The authors found that delivering this SABR regimen was feasible and well tolerated with one grade 3 toxicity (transient fatigue) and no grade 4–5 toxicities. Most patients sustained only transient minor side effects (78%) or no treatment-related side effects (18%). The mean baseline estimated GFR was 55 mL/min, which decreased to 44 mL/min at 1 year, and was maintained for those with 2 years follow-up.

Similarly, short-term efficacy appears promising. With a median follow-up of 24 months, freedom from local progression at 2 years was 100%, with one patient subsequently progressing locally with concurrent distant metastases 28 months after treatment. Local progression was defined using Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors (RECIST) v1.1. This is a pragmatic definition and takes into account the challenges in interpreting standard imaging after SABR and the difficulties in obtaining and interpreting repeat biopsies in this cohort. Similarly to the study by Sun et al. [6] it appears that stable or partial radiological responses will predominate in the early years after SABR and, unlike thermal ablation, changes in enhancement patterns can be very slow to evolve.

Longer-term follow-up is required to confirm these promising tumour control and nephron preservation rates, in addition to evaluating longer-term late effects. To that end, the present study has provided a platform for the authors to launch an international phase II clinical trial under the auspices of the TransTasman Radiation Oncology Group (TROG 15.03 FASTRACK, clinicaltrials.gov ID NCT02613819). Larger-scale prospective studies are essential to confirm the efficacy and safety of this non-invasive, nephron-sparing, ablative technique and provide further information to help refine patient selection and develop better biomarkers of response.

2 Andrews DW, Scott CB , Sperduto PW et al. Whole brain radiation therapy with or without stereotactic radiosurgery boost for patients with one to three brain metastases: phase III results of the RTOG 9508 randomised trial. Lancet (London, England) 2004; 363: 1665–72

Article of the Week: Stereotactic ablative body radiotherapy for inoperable primary kidney cancer: a prospective clinical trial

Every week the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Week from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to the article itself, there is an accompanying editorial written by a prominent member of the urological community. This blog is intended to provoke comment and discussion and we invite you to use the comment tools at the bottom of each post to join the conversation.

If you only have time to read one article this week, it should be this one.

Stereotactic ablative body radiotherapy for inoperable primary kidney cancer: a prospective clinical trial

Abstract

Objective

To assess the feasibility and safety of stereotactic ablative body radiotherapy (SABR) for renal cell carcinoma (RCC) in patients unsuitable for surgery. Secondary objectives were to assess oncological and functional outcomes.

Materials and Methods

This was a prospective interventional clinical trial with institutional ethics board approval. Inoperable patients were enrolled, after multidisciplinary consensus, for intervention with informed consent. Tumour response was defined using Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors v1.1. Toxicities were recorded using Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v4.0. Time-to-event outcomes were described using the Kaplan–Meier method, and associations of baseline variables with tumour shrinkage was assessed using linear regression. Patients received either single fraction of 26 Gy or three fractions of 14 Gy, dependent on tumour size.

Results

Of 37 patients (median age 78 years), 62% had T1b, 35% had T1a and 3% had T2a disease. One patient presented with bilateral primaries. Histology was confirmed in 92%. In total, 33 patients and 34 kidneys received all prescribed SABR fractions (89% feasibility). The median follow-up was 24 months. Treatment-related grade 1–2 toxicities occurred in 26 patients (78%) and grade 3 toxicity in one patient (3%). No grade 4–5 toxicities were recorded and six patients (18%) reported no toxicity. Freedom from local progression, distant progression and overall survival rates at 2 years were 100%, 89% and 92%, respectively. The mean baseline glomerular filtration rate was 55 mL/min, which decreased to 44 mL/min at 1 and 2 years (P < 0.001). Neutrophil:lymphocyte ratio correlated to % change in tumour size at 1 year, r2 = 0.45 (P < 0.001).

Conclusion

The study results show that SABR for primary RCC was feasible and well tolerated. We observed encouraging cancer control, functional preservation and early survival outcomes in an inoperable cohort. Baseline neutrophil:lymphocyte ratio may be predictive of immune-mediated response and warrants further investigation.

AUS outcomes in irradiated vs non-irradiated patients

Outcomes of artificial urinary sphincter implantation in the irradiated patient

Niranjan J. Sathianathen, Sean M. McGuigan* and Daniel A. Moon*

Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, Monash University, and *Epworth HealthCare, Melbourne, Vic., Australia

OBJECTIVES

• To present the outcomes of men undergoing artificial urinary sphincter (AUS) implantation.

• To determine the impact a history of radiation therapy has on the outcomes of prosthetic surgery for stress urinary incontinence.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

• A cohort of 77 consecutive men undergoing AUS implantation for stress urinary incontinence after prostate cancer surgery, including 29 who had also been irradiated, were included in a prospective database and followed up for a mean period of 21.2 months.

• Continence rates and incidence of complications, revision and cuff erosion were evaluated, with results in irradiated men compared with those of men who had undergone radical prostatectomy alone.

• The effect of co-existing hypertension, diabetes mellitus and surgical approach on outcomes were also examined.

RESULTS

• Overall, the rate of social continence (0–1 pad/day) was 87% and similar in irradiated and non-irradiated men (86.2 vs 87.5%). Likewise, the incidence of infection (3.4 vs 0%), erosion (3.4 vs 2.0%) and revision surgery (10.3 vs 12.5%) were not significantly different between the groups.

• There was a far greater incidence of co-existing urethral stricture disease in irradiated patients (62.1 vs 10.4%) which often complicated management; however, AUS implantation was still feasible in these men and, in four such cases, a transcorporal cuff placement was used.

• There were poorer outcomes in patients with diabetes, and a greater re-operation rate in those men who underwent a transverse scrotal rather than perineal surgical approach, although the differences did not reach statistical significance.

CONCLUSIONS

• Previous irradiation in patients may increase the complexity of treatment because of a greater incidence of co-existing urethral stricture disease; however, these patients are still able to achieve a level of social continence similar to that of non-irradiated patients, with no discernable increase in complication rates, cuff erosion or the need for revision surgery.

• AUS implantation remains the ‘gold standard’ for management of moderate-to-severe stress urinary incontinence in both irradiated and non-irradiated patients after prostate cancer treatment.

Radiation within urology: challenges and triumphs

As gatekeepers urologists remain at the frontline of urological oncology in a position of trust that they have held since Charles Huggins, Nobel Laureate in Urology, pioneered the use of hormone manipulation to treat prostate cancer. However, radiation within urology is an important adjunctive, palliative and even primary treatment method for many urological malignancies. However, within many spheres, particularly internationally regarding prostate cancer, tensions appear to have been simmering between urologists and radiation oncologists. Fortunately, this does not appear to be the case in Australia and New Zealand but it is an important time to reflect on such issues as we move ever forward in the multimodality era.

As gatekeepers urologists remain at the frontline of urological oncology in a position of trust that they have held since Charles Huggins, Nobel Laureate in Urology, pioneered the use of hormone manipulation to treat prostate cancer. However, radiation within urology is an important adjunctive, palliative and even primary treatment method for many urological malignancies. However, within many spheres, particularly internationally regarding prostate cancer, tensions appear to have been simmering between urologists and radiation oncologists. Fortunately, this does not appear to be the case in Australia and New Zealand but it is an important time to reflect on such issues as we move ever forward in the multimodality era.

In the USA the use of self-referral by urologists of men for adjuvant radiotherapy (RT) has come under scrutiny. Some urology groups have integrated intensity modulated RT (IMRT), a RT treatment carrying a high reimbursement rate, into their practice. This was highlighted in a recent New England Journal of Medicine article where the rate of IMRT use by urologists working at National Comprehensive Cancer Network centres remained stable at 8% but increased by 33% among matched self-referring urology groups [1]. This study has been criticised for bias but nonetheless captured political and academic attention. Certainly this situation has not arisen in our hemisphere but it remains important we think critically of what treatments we offer our patients and ensure patient’s best interests are maintained.

Clearly more research is required as to who should be receiving adjuvant RT and at what stage. In the latest issue of the BJUI USANZ supplement we highlight the Radiotherapy – Adjuvant vs Early Salvage (RAVES) trial for prostate cancer biochemical failure and high-risk disease [2]. There is no doubt this is an important trial because to date we have been unable to establish exactly which patients should receive adjuvant RT and when. Recruitment has been challenging as patients doing well after surgery often do not want additional treatment and a very small subset who are still recovering want to be enrolled but due to timing missing eligibility. Enthusiastic patients also may demand treatment rather than be randomised. Critics would also argue that the trial can never really answer the question because many men not requiring adjuvant RT will receive it [3]. Ongoing support of all parties should achieve accrual and in time, robust data. Excitingly imaging with MRI and other modalities will ensure further trials to assist in identifying disease in the salvage setting making choices easier based on more objective data [4].

Clearly more research is required as to who should be receiving adjuvant RT and at what stage. In the latest issue of the BJUI USANZ supplement we highlight the Radiotherapy – Adjuvant vs Early Salvage (RAVES) trial for prostate cancer biochemical failure and high-risk disease [2]. There is no doubt this is an important trial because to date we have been unable to establish exactly which patients should receive adjuvant RT and when. Recruitment has been challenging as patients doing well after surgery often do not want additional treatment and a very small subset who are still recovering want to be enrolled but due to timing missing eligibility. Enthusiastic patients also may demand treatment rather than be randomised. Critics would also argue that the trial can never really answer the question because many men not requiring adjuvant RT will receive it [3]. Ongoing support of all parties should achieve accrual and in time, robust data. Excitingly imaging with MRI and other modalities will ensure further trials to assist in identifying disease in the salvage setting making choices easier based on more objective data [4].

Consumerism has driven robotic surgery [5] and is doing the same for RT but descriptions of treatment would be better placed to remain generic. The use of the term ‘radiosurgery’ has highlighted the shift away from the term ‘radical radiotherapy’. Of course the term ‘robot’ has become synonymous with radical prostatectomy but the ‘radical’ contribution remains and interestingly the term ‘robot’ has been trialled by radiotherapists: ‘image-guided robotic radiosurgery’ or its other more commonly used term Cyberknife® (Accuracy Incorporated, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Certainly this would be more accurately known as stereotactic body RT (SBRT). It is these terminology changes and continual shifts in treatment regimens that rankles many, with the old argument that RT treatment was done with inferior technology so results should be ignored receives disproportionate use at conferences. All groups need to acknowledge treatments have improved rather than disowning data from older treatment regimes. On the counter side one example from brachytherapy [6] concluded that despite the hype of improving dosimetry and reducing complications, the preoperative condition regarding erectile function and LUTS are the most important factors regarding postoperative outcome. This is almost certainly true for surgery as well. Comparison of side-effects appears unfair with grading of radiation toxicities more lenient than Clavien listed complications – an even playing field for comparison of complications is warranted.

Multimodality treatment for high-risk disease is becoming the standard of care. Urologists are beginning to embrace this regime of planned surgery with likely RT and ultimately systemic therapies. However, radiation oncologists often prefer to use radiation and hormonal manipulation and consider this ‘modified monotherapy’. Some men receive different modes of RT with concerns this leads to significantly more complications and in combination with androgen deprivation comes with all of the secondary effects of such therapy. An ideal study for such high-risk patients would randomise men to RT and androgen deprivation vs a graded multimodality treatment starting with surgery and then progressing to RT and systemic therapies when required (as some men will have T2 or T3a disease with clear margins that can be observed for a PSA rise necessitating treatment).

Complications do develop after any therapy and urologists are expertly placed to deal with them. Yet, there is a belief that RT and its long-term effects are real and these are often underplayed. This is contributed by a paucity of follow-up data beyond 5 years with primary RT. Major problems from surgery are generally able to be repatriated. However, the same may not be stated for RT complications: cystitis, stricture disease, permanent catheter drainage and chronic pain syndromes although uncommon, are not rare events and not easily remedied due to the altered tissues. Urologists are able to assist with these conditions but some feel that their efforts are unrecognised and that they share too much of the burden from somewhat surprised patients when situations are not able to be satisfactorily resolved. This reinforces the involvement by enthusiastic urologists with the patient selection and follow-up of brachytherapy and even other RT treatments being the cornerstone for ideal patient management and success.

Other areas worthy of engagement are with patients who develop a recurrence after RT treatment where the available data are sparse, making a decision even more difficult [3]. The perceived reluctance to refer RT failures to urologists in a timely fashion meaning many men are not offered salvage surgery or other options [7]. Occasionally urologists do the same with surgical failures but with multi-disciplinary teams, this is a rare event.

Communication remains a key to a multidisciplinary approach. Against the successes and strains, there are newer developments that will conspire to bring teams closer together, such as newer systemic therapies and the consideration of RT in men with oligometastatic disease. Also, based on Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) data, it appears that patients with limited metastatic disease may benefit from having treatment of the primary disease with a significant decrease in mortality (slightly more pronounced with surgery than radiation) [8]. This will ensure further debate on how far we stretch our primary treatment boundaries for the betterment of patients. Finally, use of fiducial markers and spacers will hopefully minimise morbidity and these are discussed in this supplement [9].

Just like any long-term relationship, the balance will shift at times and there has to be give and take on both sides. Many of the points in this editorial could be switched the other way with urologists at fault, so we must always be careful to be global, and not focal in our approaches. With everyone working together we have improved outcomes and survival of many with many urological malignancies. Overall, there is still harmony but room for even greater communication and collaboration as we strive towards better outcomes in future decades.

Nathan Lawrentschuk

University of Melbourne, Department of Surgery and Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, Austin Hospital and Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, Department of Surgical Oncology, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

References

- Mitchell JM. Urologists’ use of intensity-modulated radiation therapy for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2013; 369: 1629–1637

- Pearse M, Fraser-Browne C, Davis ID et al. A Phase III trial to investigate the timing of radiotherapy for prostate cancer with high-risk features: background and rationale of the Radiotherapy – adjuvant versus Early Salvage (RAVES) trial. BJU Int 2014; 113: 7–12

- Chen RC. Making individualized decisions in the midst of uncertainties: the case of prostate cancer and biochemical recurrence. Eur Urol 2013; 64: 916–919

- Thompson J, Lawrentschuk N, Frydenberg M, Thompson L, Stricker P. The role of magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis and management of prostate cancer. BJU Int 2013; 112 (Suppl. 2): 6–20

- Alkhateeb S, Lawrentschuk N. Consumerism and its impact on robotic-assisted radical prostatectomy. BJU Int 2011; 108:1874–1878

- Meyer A, Wassermann J, Warszawski-Baumann A et al. Segmental dosimetry, toxicity and long-term outcome in patients with prostate cancer treated with permanent seed implants. BJU Int 2013; 111: 897–904

- de Castro Abreu AL, Bahn D, Leslie S et al. Salvage focal and salvage total cryoablation for locally recurrent prostate cancer after primary radiation therapy. BJU Int 2013; 112: 298–307

- Cheng J. Would you really do a radical prostatectomy on a man with known metastatic prostate cancer? BJU Int BLOG posted 09 December 2013. Available at: https://www.bjuinternational.com/bjui-blog/would-you-really-do-a-radical-prostatectomy-on-a-man-with-known-metastatic-prostate-cancer/. Accessed January 2014

- Ng M, Brown E, Williams A, Chao M, Lawrentschuk N, Chee R. Fiducial markers and spacers in prostate radiotherapy: current applications. BJU Int 2014; 113: 13–20

Stunned

If you needed inspiration to pursue cognitive ergonomics as a career or hobby, you could do worse than starting with the book “Set Phasers On Stun” by Steven Casey. Presented as a series of bite-sized real-life vignettes, the book illustrates the inherent fallibility in humans who design and use systems in a very engaging manner.

The most relevant story for doctors is the titular tale about a man receiving radiation therapy for a tumour on his shoulder. Ray lay on the treatment table. The tech in the next room attempted to set the machine to an appropriate radiation dose, but accidentally turned it on to full power. She noticed her error, and reset the machine before firing. Unfortunately the software was not sufficiently powerful to acknowledge her rapid typing, and the setting stayed on full. Furthermore, after firing, the screen told the tech there was an error and that no dose had been delivered. She tried twice more, inadvertently dosing Ray each time, unable to hear Ray’s screams from the lead lined treatment room. He only avoided further doses by running away. As Ray died from the treatment over the ensuing weeks, he jokingly told people that “Captain Kirk forgot to put the machine on stun”.

As clinical doctors, we should acknowledge the fact that individually, we do not make that many people better. Disappointing though this is, as it is the Raison d’être for many of us, I think we understand on some level that it is the “Big Picture” people, the Epidemiologists and Public Health physicians that really make the difference. However many cancers I cut out in my career, I’m still likely to make less of a difference than one well in Sub-Saharan Africa. Many of us are prevented from entering the “Big Picture” career paths due to the fact that they are interminably boring. It is much more interesting to counsel and educate patients, and certainly more exciting to perform complex (and at times terrifying) operations than to sit in a small office in the medical school’s worst-funded department crunching numbers. And who is more likely to be invited to appear on Dr. Oz? The Robotic Surgeon? Or the Epidemiologist with meticulously gathered records of malaria rates in South East Asia? The sad truth of the world is that glamour and excitement are usually more revered than self-sacrifice for enduring positive change.

It took a tragedy, and software engineers to solve the problem that killed Ray on the radiation table, but fortunately, there are simpler avenues for clinicians to make a difference beyond the patients they personally treat. This does not necessarily mean being involved in research on expensive new drugs that often have an incremental (or even arguable) benefit over the existing standard. And you don’t have to be Atul Gawande, creating the WHO surgical checklist, but it helps to use his approach. Devoting some time and mental resources to identify problems that affect a large number of people, even if only in a small way adds up to a significant total benefit. This week I was sent a review article on inadvertent diathermy injuries. These are uncommon, but can be debilitating, as in the index case where a patient essentially lost the use of his right hand due to thermal injury-induced tendon contractures. A consistent problem was a loss of contact between skin and earthing plate. Sweat and traction can loosen the plate and result in occult burns, particularly during prolonged cases, or emergency cases where the plate was applied in a rush. Maybe another surgical check should be done at four, or six hours into an operation to assess the need for a second antibiotic dose, and check diathermy plate. If the case is taking significantly longer than expected, should we take the opportunity to ask; “Why is this taking so long? Do I need help, or a second opinion here?”

The electronic age has given us unprecedented opportunity to reach patients with quality information on the nature of their disease, what to expect from their surgery, and advice on when to seek urgent help. In many cases it just takes a person to assume responsibility for writing content for a web page. The more quality health content we write, the more we drown out the snake-oil merchants and charlatans that prey on credulous patients.

My challenge to you in the coming week is to devote some time to thinking of a “Big Picture” issue that could benefit more patients than those you see yourself, or alternatively dig a well in Africa.

James Duthie is a Urological Surgeon/Robotic Surgeon. Interested in Human Factors Engineering, training & error, and making people better through electronic means. Melbourne, Australia @Jamesduthie1