Article of the week: Dutch GPs influenced by ERSPC PSA study

Every week the Editor-in-Chief selects the Article of the Week from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to the article itself, there is an accompanying editorial written by a prominent member of the urological community. This blog is intended to provoke comment and discussion and we invite you to use the comment tools at the bottom of each post to join the conversation.

Finally, the third post under the Article of the Week heading on the homepage will consist of additional material or media. This week we feature a video of Miss van der Meer and Dr Blanker discussing their article.

If you only have time to read one article this week, it should be this one.

Impact of the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) on prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing by Dutch general practitioners

Saskia Van der Meer, Boudewijn J. Kollen*, Willem H. Hirdes, Martijn G. Steffens, Josette E.H.M. Hoekstra-Weebers†, Rien M. Nijman‡ and Marco H. Blanker*

Department of Urology, Isala Clinics, Zwolle, and Departments of *General Practice, †Psychosocial services and ‡Urology, University Medical Center Groningen, University of Groningen, Groningen, the Netherlands

OBJECTIVE

• To determine the impact of the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) publication in 2009 on prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level testing by Dutch general practitioners (GPs) in men aged ≥40 years.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

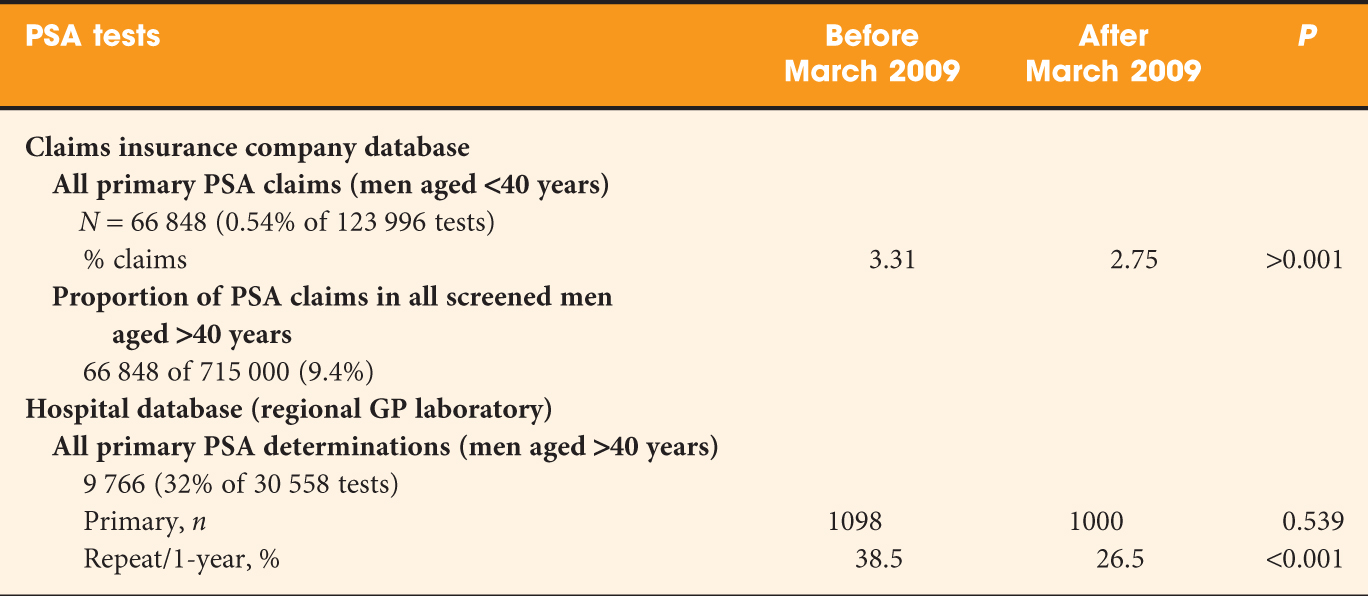

• Retrospective study with a Dutch insurance company database (containing PSA test claims) and a large district hospital-laboratory database (containing PSA-test results).

• The difference in primary PSA-testing rate as well as follow-up testing before and after the ERSPC was tested using the chi-square test with statistical significance at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

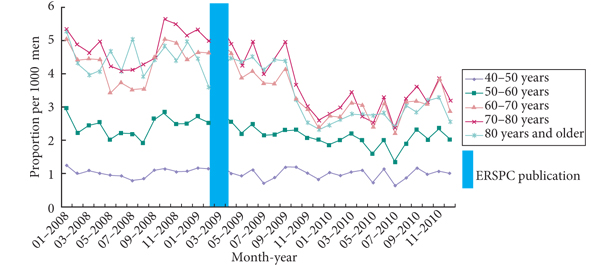

• Decline in PSA tests 4 months after ERSPC publication, especially for men aged ≥60 years.

• Primary testing as well as follow-up testing decreased, both for PSA levels of <4 ng/mL as well as for PSA levels of 4–10 ng/mL.

• Follow-up testing after a PSA level result of >10 ng/mL moderately increased (P = 0.171).

• Referral to a urologist after a PSA level result of >4 ng/mL decreased slightly after the ERSPC publication (P = 0.044).

CONCLUSIONS

• After the ERSPC publication primary PSA testing as well as follow-up testing decreased.

• Follow-up testing seemed not to be adequate after an abnormal PSA result. The reasons for this remain unclear.

Read Previous Articles of the Week