Editorial: Is zero sepsis alone enough to justify transperineal prostate biopsy?

The landscape of infectious complications after TRUS-guided biopsy of the prostate has changed dramatically. While sepsis after TRUS-guided prostate biopsy has always been a concern for urologists performing this very common procedure, in the past couple of years a number of factors have added to these pre-existing concerns for urologists and patients alike.

First, key papers have reported the true incidence of sepsis and hospital re-admission after TRUS biopsy and have shown that these rates are increasing. Loeb et al. [1] reported that the 30-day re-admission rate in a Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER)-Medicare population was 6.9% and that this rate is increasing. Nam et al. [2] similarly reported a 3.5-fold increase in hospital admissions after prostate biopsy in the previous 10 years, principally attributable to infection-related complications. These reports have been replicated around the world and there is consensus that this is a growing problem.

Second, there are increasing concerns about the emergence of resistant organisms, in particular, extended spectrum beta lactamase (ESBL), in regions where antibiotic use has contributed to the emergence of these strains [3]. Media attention has focused on this issue and has led to increased concerns among urologists and patients alike. It has also led to a requirement for extra precautions when assessing patients for prostate biopsy such that in some regions, rectal swabs are being taken to identify ESBL-carriers ahead of time. In a contemporary series, Taylor et al. [4] report that 19% of men undergoing transrectal prostate biopsy in Canada carry ciprofloxacin-resistant coliforms in rectal swabs. The thought of passing a needle through this flora into the prostate is somewhat disturbing; rectal swabs may become mandatory when offering a TRUS-guided biopsy to any patient and should absolutely be taken if planning a TRUS biopsy in someone who has travelled to South-East Asia in the preceding 6 months.

The Bloomberg News, in a well-researched report into antibiotic use in India and the emergence of resistant strains of Escherichia coli, reported some startling statistics about the overuse of antibiotics in that country, and described how the ‘perfect storm’ of antibiotic overuse, poverty and poor sanitation (half of the country’s 1.2 billion residents defaecate in the open), is contributing to the emergence of superbugs colonizing the gut of dwellers and visitors to India [5]. It is clear that even walking through a puddle in New Delhi puts a visitor at high risk of harbouring ESBL organisms in the rectum for many months after.

In this month’s BJUI, Vyas et al. [6] describe a consecutive series of 634 patients undergoing prostate biopsy at Guy’s Hospital in London using a transperineal template-guided approach, and report a sepsis rate of zero. They also report other notable factors including a 36% cancer detection rate in men who had previously undergone transrectal prostate biopsy with no evidence of malignancy and, in men on active surveillance for Gleason 6 prostate cancer, they observed upgrading to Gleason ≥7 cancer in 29% of cases after immediate re-staging biopsy using a transperineal approach. An even larger contemporary study from Pepe et al. [7] reports zero sepsis in a consecutive series of 3000 men undergoing transperineal prostate biopsy.

It is quite impossible to imagine such large series of prostate biopsies with no episodes of sepsis if performed using a transrectal approach. The documented increasing levels of ESBL and high levels of asymptomatic gut colonization, especially for those resident or travelling through South-East Asia, mean that adequate risk assessment and counselling of patients before TRUS biopsy is more important than ever before. A careful history regarding recent antibiotic use is also essential as previous recent use of quinolones is also a risk factor for infection after a transrectal biopsy [8].

While widespread adoption of a transperineal approach to prostate biopsy would have considerable resource and logistic issues, and inevitably would not be accepted by all urologists, the rising rate of infectious complications and of resistant organisms colonizing the rectum may mean that continuing with a transrectal approach becomes too risky and therefore unacceptable to patients and clinicians alike. While a transperineal approach also appears to add value in terms of more accurate staging and also facilitates the emerging interest in MRI fusion-guided biopsies and focal therapy, zero sepsis alone may be enough to convince many that a transrectal approach should no longer be preferred.

Declan G. Murphy*†, Mahesha Weerakoon† and Jeremy Grummet‡

*Division of Cancer Surgery, University of Melbourne, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, †Australian Prostate Cancer Research Centre, Epworth Richmond Hospital, and ‡Department of Urology, The Alfred Hospital, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

References

- Loeb S, Carter HB, Berndt SI, Ricker W, Schaeffer EM. Complications after prostate biopsy: data from SEER-Medicare. J Urol 2011; 186: 1830–1834

- Nam RK, Saskin R, Lee Y et al. Increasing hospital admission rates for urological complications after transrectal ultrasound guided prostate biopsy. J Urol 2010; 183: 963–968

- Williamson DA, Masters J, Freeman J, Roberts S. Travel-associated extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli bloodstream infection following transrectal ultrasound-guided prostate biopsy. BJU Int 2012; 109: E21–22

- Taylor S, Margolick J, Abughosh Z et al. Ciprofloxacin resistance in the faecal carriage of patients undergoing transrectal ultrasound guided prostate biopsy. BJU Int 2013; 111: 946–953

- Gale JN, Narayan A. Drug-defying germs from India speed post-antibiotic era. 2012; Available at: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-05-07/drug-defying-germs-from-india-speed-post-antibiotic-era.html. Accessed June 2014

-

Vyas L, Acher P, Challacombe B et al. Indications, results and safety profile of transperineal sector biopsies of the prostate: a single centre experience of 634 cases. BJU Int 2014; 114: 32–37

- Pepe PA, Aragona F. Morbidity after transperineal prostate biopsy in 3000 patients undergoing 12 vs 18 vs more than 24 needle cores. Urology 2013; 81: 1142–1146

- Patel U, Dasgupta P, Amoroso P, Challacombe B, Pilcher J, Kirby R. Infection after transrectal ultrasonography-guided prostate biopsy: increased relative risks after recent international travel or antibiotic use. BJU Int 2012; 109: 1781–1785

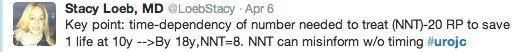

In this week’s edition of the NEJM, Anna Bill-Axelson and the Scandinavian Prostate Cancer Group Study Number 4 (SPCG-4) investigators have

In this week’s edition of the NEJM, Anna Bill-Axelson and the Scandinavian Prostate Cancer Group Study Number 4 (SPCG-4) investigators have