Editorial – Prostate cancer surgery vs radiation: has the fat lady sung?

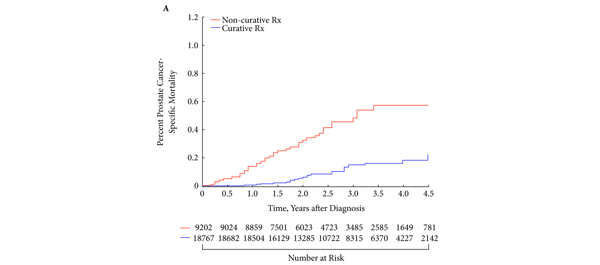

The current article by Sun et al. [1] representing a number of institutions involved in prostate cancer treatment provision is thought-provoking and hypothesis-generating. The authors contention when mining Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results data for 67 000 men who had localized prostate cancer between 1988 and 2005 is that those with a life expectancy >10 years had less likelihood of prostate cancer death when treated with surgery rather than by radiotherapy or being left to observation. The Scandinavians have already shown, in the randomized study by Hugosson et al. [2], that if you have your prostate cancer removed you have less likelihood of symptomatic local recurrence, lower likelihood of metastasis and progression, and a 29% reduced likelihood of prostate cancer death. The current study asks the question ‘Is radiation therapy less likely to provide a long-term cure for prostate cancer than surgery?’ and gives an answer in the affirmative.

The current paper, in its way, neatly encapsulates the contemporary angst generated in the community when prostate cancer screening, diagnosis and therapy are discussed. The Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening (PLCO) trial [3] allegedly shows no benefit from treatment over observation and contends perhaps that we surgeons and radiation oncologists are harm-workers, not life-savers. The PLCO has a 52% PSA contamination in its control arm [3]. That flawed trial compared screening with de facto screening and produced, in my view, a null hypothesis. How do we explain the paradox of a 44% reduction in prostate cancer-specific mortality between 1993 and 2009? How do we explain the disconnect between these trials and the facts? What do we do with the data not yet considered by the expert panels showing that early PSA testing at age <50 years is highly predictive of subsequent lethal prostate cancer? [4]

Clinicians are rapidly moving to an era of judicious risk assessment. This can only be done after biopsy is performed. We now frequently enrol patients with apparently indolent prostate cancer into surveillance protocols [5]. So the question should be ‘If the disease found on biopsy is moderate to high risk, and potentially lethal for that man, should we remove his prostate surgically or radiate it with intensity-modulated radiation therapy, brachytherapy, proton therapy, +/- hormone therapy?’.

As a surgeon I have an inherent dislike of combining hormone therapy in primary treatment. At least 50% of men in high-risk prostate cancer cohorts who receive radiation therapy also receive hormone therapy as adjuvant or neoadjuvant treatment [6]. Hormone therapy has a myriad of side effects. Even if the playing field was level between surgery and radiation therapy, the avoidance of hormone therapy as a first-line treatment gives surgery a seductive advantage.

The authors of the current report show a significant survival advantage in the cohort for surgery over radiation therapy and observation. There will never be a randomized trial between the two potentially curative treatment methods surgery and radiation. The scourge of commercial interest with spurious claims of superiority of one form of therapy over another, proton beam vs intensity-modulated radiation therapy, robotics vs high-intensity focused ultrasonography, means that we risk having our decisions regarding appropriate therapy formed by multibillion dollar technology companies with powerful marketing capacity. The current paper confirms what is self-evident: untreated localized prostate cancer can be lethal. Surgery and radiation therapy lower the morbidity and mortality from prostate cancer. Which is the better method of curative therapy is moot, but we do know that cure is very much predicated on the expertise and location of the practitioner.

We know mostly when and who to treat and what treatments work well. In my view, the prostate cancer testing debate resonates with the contemporary discussion about childhood immunization for infectious diseases. Some parents now, who clearly cannot remember the devastating epidemics of polio and other childhood illnesses, refuse to immunize their children. Prostate cancer practitioners who did not live in the quite recent era where the initial presentation of prostate cancer was bone metastasis +/− crush fracture to the vertebra and sometimes paraplegia, may be unknowingly steering us backwards.

At the recent 2013 AUA meeting, Adams et al. [7] reported on the fate of men not screened for prostate cancer, i.e. those men who presented with a PSA >100 ng/mL. There was a 3-year survival rate of 9.7%, a 19.7% cord compression rate and a 64% hospitalization rate. Those who do not learn the lessons of history are condemned to repeat them.

Anthony J. Costello

Department of Surgery, Royal Melbourne Hospital, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia

References

- Sun M, Sammon JD, Becker A et al. Radical prostatectomy vs radiotherapy vs observation among older patients with clinically localized prostate cancer: a comparative effectiveness evaluation. BJU Int 2014; 113: 200–208

- Hugosson J, Carlsson S, Aus G et al. Mortality results from the Goteborg randomised population-based prostate-cancer screening trial. Lancet Oncol 2010; 11: 725–732

- Andriole GL, Crawford ED, Grubb RL 3rd et al. Prostate cancer screening in the randomized Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial: mortality results after 13 years of follow-up. J Natl Cancer Inst 2012; 104: 125–132

- Vickers AJ, Ulmert D, Sjoberg DD et al. Strategy for detection of prostate cancer based on relation between prostate specific antigen at age 40–55 and long term risk of metastasis: case-control study. BMJ 2013; 346: f2023

- Evans SM, Millar JL, Davis ID et al. Patterns of care for men diagnosed with prostate cancer in Victoria from 2008 to 2011. Med J Aust 2013; 198: 540–545

- Cooperberg MR, Vickers AJ, Broering JM, Carroll PR. Comparative risk-adjusted mortality outcomes after primary surgery, radiotherapy, or androgen-deprivation therapy for localized prostate cancer. Cancer 2010; 116: 5226–5234

- Adams W, Elliott CS, Reese JH. The fate of men presenting with PSA over 100 ng/mL: what happens when we do not screen for prostate cancer? AUA 2013. Abstract 2696

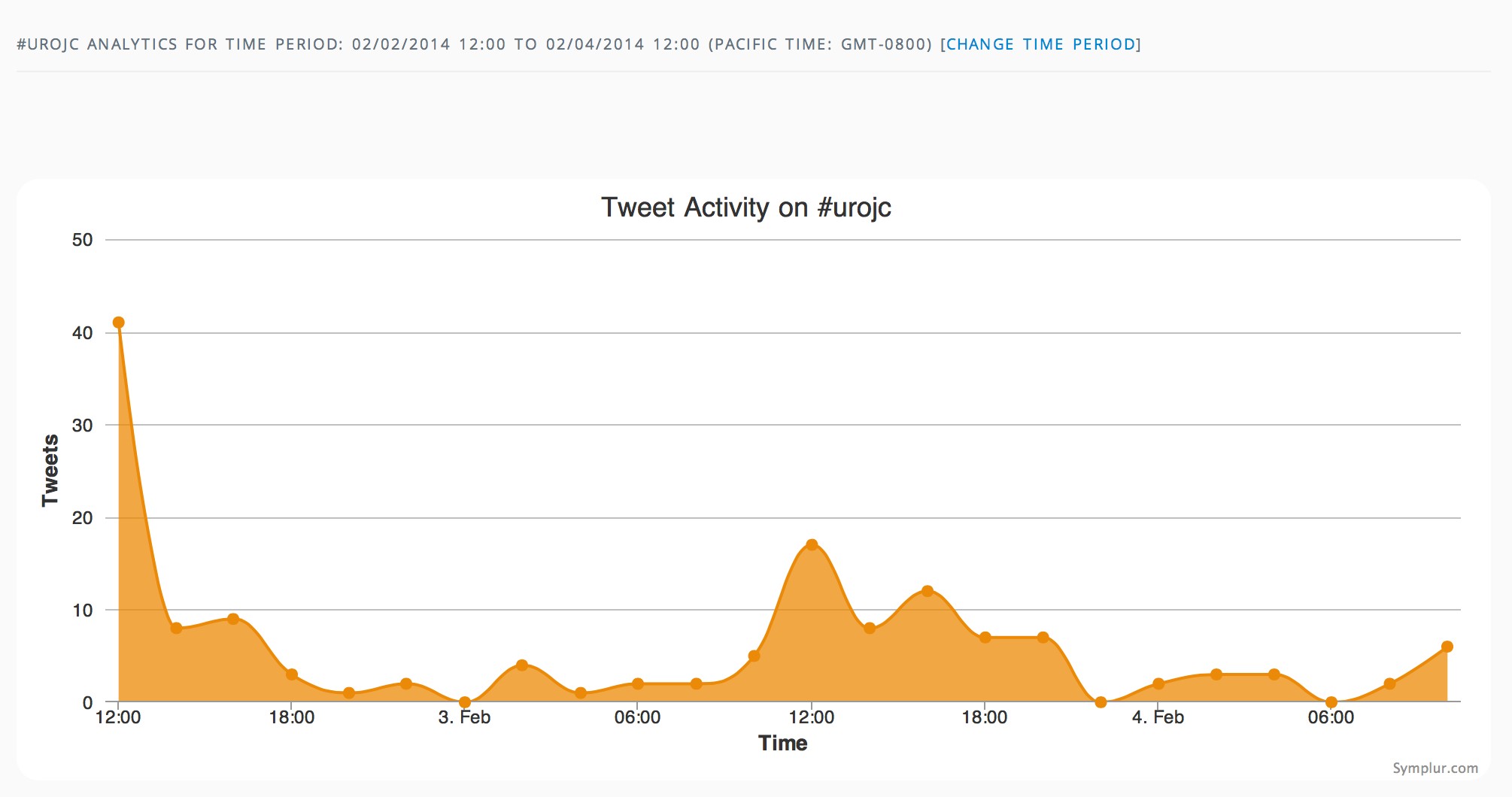

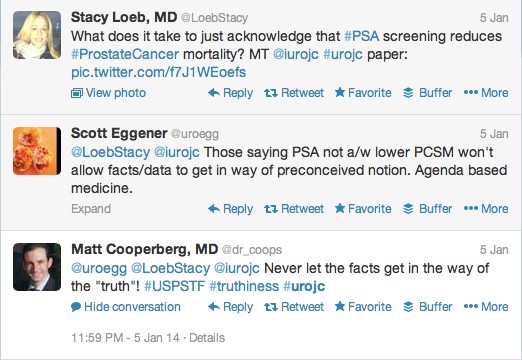

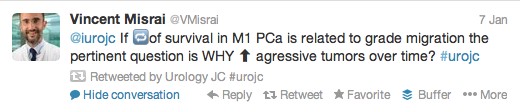

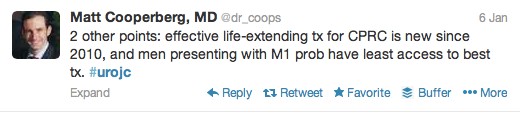

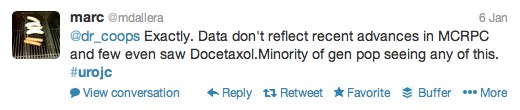

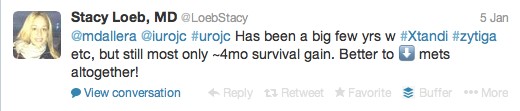

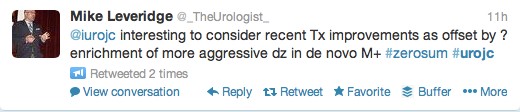

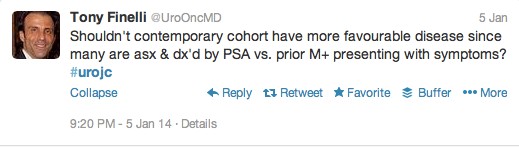

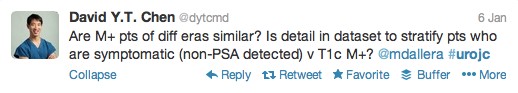

The first International Journal Club of 2014 pulled momentum from December’s discussion on treatment of metastatic prostate cancer. The study reported retrospective review of the California Cancer Registry (CCR) from 1988 to 2009 and found no significant improvement in overall or disease-specific survival in men presenting with metastatic prostate cancer. [1] Senior author Marc Dall’Era (

The first International Journal Club of 2014 pulled momentum from December’s discussion on treatment of metastatic prostate cancer. The study reported retrospective review of the California Cancer Registry (CCR) from 1988 to 2009 and found no significant improvement in overall or disease-specific survival in men presenting with metastatic prostate cancer. [1] Senior author Marc Dall’Era (

Over 2 million people in England have a diagnosis of cancer. This is such a large problem, the Department of Health is spending £750 million on improving earlier diagnosis and prevention of cancer, yet at the same time, £20 billion of efficiency savings must be made. One arm of post-cancer care is survivorship. Survivorship care was initially developed in the USA 20 years ago, starting with breast cancer patients. Prostate cancer survivorship care has been lagging far behind.

Over 2 million people in England have a diagnosis of cancer. This is such a large problem, the Department of Health is spending £750 million on improving earlier diagnosis and prevention of cancer, yet at the same time, £20 billion of efficiency savings must be made. One arm of post-cancer care is survivorship. Survivorship care was initially developed in the USA 20 years ago, starting with breast cancer patients. Prostate cancer survivorship care has been lagging far behind.