Posts

Article of the week: Ultrasound guidance can be used safely for renal tract dilatation during percutaneous nephrolithotomy

Every week, the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Week from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to the article itself, there is an editorial written by a prominent member of the urological community and a visual abstract prepared by a trainee urologist; we invite you to use the comment tools at the bottom of each post to join the conversation.

If you only have time to read one article this week, we recommend this one.

Ultrasound guidance can be used safely for renal tract dilatation during percutaneous nephrolithotomy

Manuel Armas-Phan*, David T. Tzou*†, David B. Bayne*, Scott V. Wiener*, Marshall L. Stoller* and Thomas Chi*

*Department of Urology, University of California, San Francisco, CA and †Division of Urology, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA

Abstract

Objectives

To compare clinical outcomes in patients who underwent percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) with renal tract dilatation performed under fluoroscopic guidance vs renal tract dilatation with ultrasound guidance.

Patients and Methods

We conducted a prospective observational cohort study, enrolling successive patients undergoing PCNL between July 2015 and March 2018. Included in this retrospective analysis were cases where the renal puncture was successfully obtained with ultrasound guidance. Cases were then grouped according to whether fluoroscopy was used to guide renal tract dilatation or not. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 15.1 including univariate (Fisher’s exact test, Welch’s t‐test) and multivariate analyses (binomial logistic regression, ordinal logistic regression, and linear regression).

Results

A total of 176 patients underwent PCNL with successful ultrasonography‐guided renal puncture, of whom 38 and 138 underwent renal tract dilatation with fluoroscopic vs ultrasound guidance, respectively. There were no statistically significant differences in patient age, gender, body mass index (BMI), preoperative hydronephrosis, stone burden, procedure laterality, number of dilated tracts, and calyceal puncture location between the two groups. Among ultrasound tract dilatations, a higher proportion of patients were placed in the modified dorsal lithotomy position as opposed to prone, and a significantly shorter operating time was observed. Only modified dorsal lithotomy position remained statistically significant after multivariate regression. There were no statistically significant differences in postoperative stone clearance, complication rate, or intra‐operative estimated blood loss. A 5‐unit increase in a patient’s BMI was associated with 30% greater odds of increasingly severe Clavien–Dindo complications. A 5‐mm decrease in the preoperative stone burden was associated with 20% greater odds of stone‐free status. No variables predicted estimated blood loss with statistical significance.

Conclusions

Renal tract dilatation can be safely performed in the absence of fluoroscopic guidance. Compared to using fluoroscopy, the present study demonstrated that ultrasonography‐guided dilatations can be safely performed without higher complication or bleeding rates. This can be done using a variety of surgical positions, and future studies centred on improving dilatation techniques could be of impactful clinical value.

Editorial: Zero‐radiation stone treatment

In this month’s BJUI, Armas‐Phan et al. [1] report on a prospective observational trial of fluoroscopic vs ultrasound (US)‐guided tract dilatation during percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL). A total of 176 patients underwent successful initial US‐only guided puncture; of these patients, 138 had US‐only dilatation, while in 38 fluoroscopy was required. The authors found no difference in patient factors (e.g. age, gender, body mass index [BMI]) or stone factors (hydronephrosis, stone burden, number of tracts or puncture location). On multivariate analysis, US dilatation was more likely to be performed in the modified dorsal lithotomy position (compared to prone), but there was no significant difference in important outcomes such as stone clearance, complication rates or blood loss.

Whilst only reporting on access (and not necessarily dilatation), the Clinical Research Office of the Endourological Society PCNL Global Study shows us that worldwide fluoroscopic access is by far the most common (88.3% of cases) [2] and there are relatively few reports of US‐guided dilatation in the literature. The technique does produce technical challenges as the surgeon needs to confidently identify the depth of the dilators or balloon and be sure of its location relative to calyceal anatomy. Whilst dilating short is not usually a problem as simply re‐dilating can be done, dilating too far carries serious risk of perforation of the pelvicalyceal system and vascular injury. The authors’ described technique does rely on good kidney and guidewire visualisation, and if this is not possible then fluoroscopy is used instead. Thus, even in this series with experts at this technique, 38 (22%) underwent fluoroscopic dilatation after US‐guided puncture, and of the 138 with intended US dilatation, seven (5%) were converted to fluoroscopy. Furthermore, 115 patients never entered this series as they underwent initial fluoroscopic‐guided puncture. Thus, it is important to realise that this is a series of select patients being treated by expert enthusiasts of this technique and fluoroscopy should be available in the operating theatre, as it is not possible to do this technique for all patients. In particular, obesity limits the visualisation under US and the authors have previously shown that renal access drops from 76.9% of normal‐weight patients (BMI <25 kg/m2) to 45.6% for those classified as obese (BMI >30 kg/m2) [3]. An alternative strategy to avoid radiation is to use endoscopic combined intrarenal surgery (ECIRS), as the depth of dilatation can be monitored by direct visualisation via the flexible ureteroscope.

Patients and healthcare professionals are increasingly aware of the risks posed by ionising radiation. Ferrandino et al. [4] analysed radiation exposure of patients presenting with acute stone episodes in an American setting. The mean dose was a staggering 29.7 mSv and 20% of patients received >50 mSV. There is also awareness of risk to the operating staff from endourological procedures and although doses are relatively low [5], these can accumulate during a lifetime of operating, with risks of not only malignancy but also cataract formation [6]. Whilst I am sure we all wear protective lead gowns in the operating theatre, how many people wear lead glasses? A recent study showed that, at typical workload, the annual dose to the lens of the eye was 29 mSv in interventional endourology [7].

As urologists, we should all be aware of these risks and follow the ALARA (As Low As Reasonably Achievable) principals of keeping doses to a minimum. Thus, this paper [1] is particularly welcome and shows zero‐radiation procedures can be safely performed. The authors now attempt this technique for all PCNL procedures and achieve US‐only puncture and dilatation in over half of their patients. Hopefully, this paper will inspire us all to look at reducing or eliminating radiation usage in our stone procedures and this will be good for patients and surgeons alike.

by Matt Bultitude

References

- , , et al. Ultrasound guidance can be used safely for renal tract dilatation during percutaneous nephrolithotomy. BJUI 2019; 125: 284-91

- , , et al. The Clinical Research Office of the Endourological Society Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy Global Study: indications, complications, and outcomes in 5803 patients. J Endourol 2011; 25: 11– 7

- , , , , . Ultrasound guidance to assist percutaneous nephrolithotomy reduces radiation exposure in obese patients. Urology 2016; 98: 32– 8

- , , et al. Radiation exposure in the acute and short‐term management of urolithiasis at 2 academic centers. J Urol 2009; 181: 668– 72

- , , et al. Surgical staff radiation protection during fluoroscopy‐guided urologic interventions. J Endourol 2016; 30: 638– 43

- , , et al. Risk of radiation‐induced cataracts: investigation of radiation exposure to the eye lens during endourologic procedures. J Endourol 2018; 32: 897– 903

- , , et al. Risk of radiation exposure to medical staff involved in interventional endourology. Radiat Prot Dosimetry 2015; 165: 268– 71

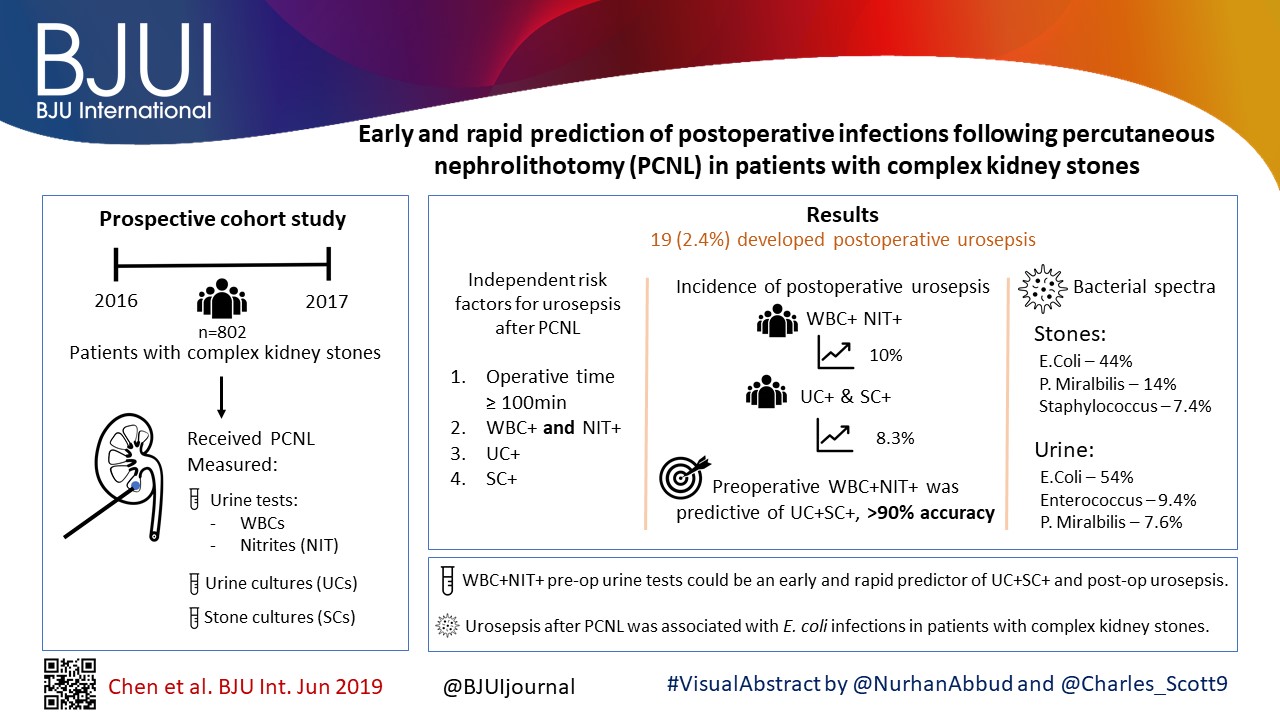

Article of the week: Early and rapid prediction of postoperative infections following PCNL in patients with complex kidney stones

Every week, the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Week from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to the article itself, there is an editorial and a visual abstract prepared by prominent members of the urological community. These are intended to provoke comment and discussion and we invite you to use the comment tools at the bottom of each post to join the conversation.

If you only have time to read one article this week, it should be this one.

Early and rapid prediction of postoperative infections following percutaneous nephrolithotomy in patients with complex kidney stones

Dong Chen*, Chonghe Jiang†, Xiongfa Liang*, Fangling Zhong*, Jian Huang*, Yongping Lin‡, Zhijian Zhao*, Xiaolu Duan*, Guohua Zeng* and Wenqi Wu*

*Department of Urology, Guangdong Key Laboratory of Urology, Minimally Invasive Surgery Center, The First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou, †Department of Urology, The People’s Hospital of Qingyuan City, The Sixth Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, Qingyuan, and ‡Department of Laboratory Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China

Abstract

Objectives

To obtain more accurate and rapid predictors of postoperative infections following percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) in patients with complex kidney stones, and provide evidence for early prevention and treatment of postoperative infections.

Patients and Methods

A total of 802 patients with complex kidney stones who underwent PCNL, from September 2016 to September 2017, were recruited. Urine tests, urine cultures (UCs) and stone cultures (SCs) were performed, and the perioperative data were prospectively recorded.

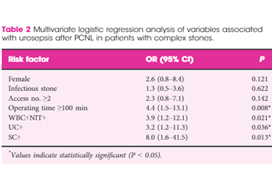

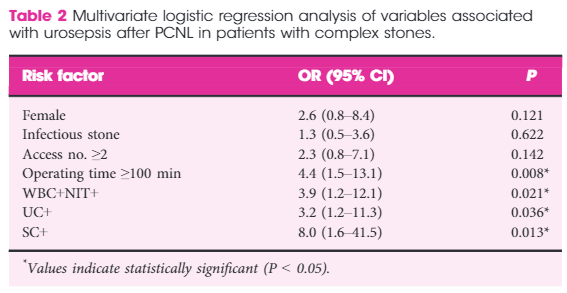

Results

In all, 19 (2.4%) patients developed postoperative urosepsis. A multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that an operating time of ≥100 min, urine test results with both positive urine white blood cells (WBC+) and positive urine nitrite (WBC+NIT+), positive UCs (UC+), and positive SCs (SC+) were independent risk factors of urosepsis. The incidence of postoperative urosepsis was higher in patients with WBC+NIT+ (10%) or patients with both UC+ and SC+ (UC+SC+; 8.3%) than in patients with negative urine test results or negative cultures (P < 0.01). Preoperative WBC+NIT+ was predictive of UC+SC+, with an accuracy of >90%. The main pathogens found in kidney stones were Escherichia coli (44%), Proteus mirabilis (14%) and Staphylococcus (7.4%); whilst the main pathogens found in urine were E. coli (54%), Enterococcus (9.4%) and P. mirabilis (7.6%). The incidence of E. coli was more frequent in the group with urosepsis than in the group without urosepsis (P < 0.05).

Conclusions

WBC+NIT+ in preoperative urine tests could be considered as an early and rapid predictor of UC+SC+ and postoperative urosepsis. Urosepsis following PCNL was strongly associated with E. coli infections in patients with complex kidney stones.

Editorial: Predicting sepsis after percutaneous nephrolithotomy

In this month’s BJUI, Chen et al. [1] report on a large series of percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) procedures from Guangzhou in China. The authors studied patients who developed postoperative urosepsis and looked for any predictive factors that would herald impending sepsis.

In this latest report, the authors analysed 802 patients with complex kidney stones undergoing PCNL in a single centre. ‘Complex’ was defined as complete staghorn, partial staghorn or pelvic stone with at least two calyceal stones. Midstream urines (MSU) were collected and analysed for white blood cells (WBC) and nitrites (NIT). Antibiotics were given preoperatively if the urine culture (UC) was positive for WBC (WBC+) or NIT (NIT+). Standard single‐dose antibiotic was given on induction of anaesthesia and only continued for 48 h if the culture was positive. Stone cultures (SCs) were routinely collected. Of the 802 patients, UCs were positive (UC+) in 171 (21%) and SCs subsequently positive (SC+) in 30%. Postoperatively, 98 (12%) developed a fever, 62 (7.7%) developed systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), and 19 (2.4%) developed sepsis as defined by the quick Sequential (sepsis‐related) Organ Failure Assessment (qSOFA).

Multiple factors were significantly associated with sepsis: female sex (79% vs 40%), infection stone (47% vs 21%), long operating time ≥100 min (74% vs 45%), multiple accesses (32% vs 10%), UC+ (63% vs 20%), SC+ (89% vs 29%), fever (74% vs 11%), as well as being both WBC+ and NIT+ (63% vs 13%). Conversely, if WBC and NIT were negative (WBC–NIT–) the risk of sepsis was only 5.3%. On multivariate analysis SC+ (odds ratio [OR] 8.0), operating time ≥100 min (OR 4.4), WBC+ and NIT+ (OR 3.9), UC+ (OR 3.2), were independent risk factors for sepsis. Not surprisingly having UC+, SC+ or both showed a statistically higher incidence of fever, SIRS, and sepsis. Being WBC+ and NIT+ was the best predictor of having both UC+ and SC+ with an impressive 92% sensitivity and 98% specificity.* Similarly, WBC+ and NIT+ was the best predictor of sepsis with 92% sensitivity and 82% specificity. The absolute risk of sepsis was only 0.2% if WBC–NIT–, 2.8% if only one was positive, and 10% if WBC+NIT+.

The authors also report on the bacterial findings of the UCs and SCs. In the SCs, Escherichia coli (44%), Proteus mirabilis (14%) and Staphylococcus (7.4%) were the most common; whilst in the UCs, E. coli (54%), Enterococcus (9.4%) and P. mirabilis (7.6%) were predominant. It is important to remember the potential differences when interpreting UCs preoperatively and to ensure broad‐spectrum cover is given and this justifies the sending of SCs, particularly in high‐risk patients [1].

The recognition of early sepsis is paramount and has been recognised in previous studies leading to the ‘golden hour’, when early aggressive treatment of the infection has been shown to lead to better outcomes [2]. In a large study by Kumar et al. [2], early antimicrobial administration (within the first hour of hypotension from septic shock) led to a higher overall survival; but worryingly, only 50% of patients received appropriate antibiotics within 6 h. Thus, if high‐risk patients could be predicted then closer monitoring, aggressive fluid management, and early broad‐spectrum antibiotics with intensive care support could be targeted at those specific patients.

There are multiple definitions for infection, e.g., sepsis, severe sepsis, septic shock, and SIRS. The 2016 International Consensus attempted to clarify these and defined sepsis as ‘A life‐threatening organ dysfunction due to dysregulated host response to infection’ [3]. They found the term ‘severe sepsis’ to be obsolete. Septic shock is defined as ‘a subset of sepsis in which particularly profound circulatory, cellular, and metabolic abnormalities are associated with a greater risk of mortality than with sepsis alone’ [3]. The Consensus recommended organ dysfunction is assessed by a SOFA score increase of ≥2, as this is associated with a mortality of 10%. This then led to the bedside assessment clinical score called qSOFA. Poorer outcomes were associated with two or more of the qSOFA criteria: respiratory rate ≥22 breaths/min, altered mentation (as judged by the Glasgow Coma Scale), and systolic blood pressure ≤100 mmHg.

In this current study [1], many of the factors associated with postoperative sepsis are logical and have been demonstrated before, e.g., female sex, infection stone, prolonged operating times, and multiple accesses. This paper has shown that careful attention to the preoperative urine dipstick can provide important prediction of potential severe infective complications postoperatively. In an era of antibiotic stewardship this could help guide targeted preoperative and prolonged postoperative antibiotics for a small group of patients, whilst managing WBC–NIT– patients with standard prophylaxis only. The high‐risk group should also be observed very closely postoperatively and moved to a high‐dependence setting rapidly if clinical signs of sepsis develop. It would also suggest that in this high‐risk group, operating times and intra‐renal pressure should be minimised. It may be that in these patients it is better to use larger tract PCNL sizes to allow rapid fragmentation and evacuation of the stone and that consideration should be given to staged procedures in complicated stones where multiple access is being considered to minimise operating time and allow analysis of intraoperative SCs.

It should of course be remembered that antibiotic decisions should be based on local policies and sensitivities, which may be very different from this population. Rapid treatment of sepsis is paramount and the most recent ‘Hour‐1’ bundle provides the most up‐to‐date guidance for immediate resuscitation and management with lactate management, blood cultures, broad‐spectrum antibiotics, i.v. fluids, and early use of vasopressors if the blood pressure does not respond to fluid replacement [4].

by Matt Bultitude and Kay Thomas

References

- , , et al. Early and rapid prediction for postoperative infections following percutaneous nephrolithotomy in patients with complex kidney stones. BJU Int 2019; 123: 1041– 7

- , , et al. Duration of hypotension before initiation of effective antimicrobial therapy is the critical determinant of survival in human septic shock. Crit Care Med 2006; 34: 1589– 96

- , , et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis‐3). JAMA 2016; 315: 801– 10

- , , . The surviving sepsis campaign bundle: 2018 update. Crit Care Med 2018; 46: 997– 1000

BAUS/BJUI/USANZ Joint Session AUA 2019

British Association of Urological Surgeons/BJU International/Urological Society of Australia and New Zealand (BAUS/BJUI/USANZ) Joint Session AUA 2019

Sunday, May 5th 2:00 – 5.00 PM. McCormick Place Convention Center South Building – Room S102 BC

|

Registries /Smart Data /Complications – CHAIR: Duncan Summerton

|

|

| 1400-1420 | Alan Partin

A contemporary look at biomarkers for diagnosis of Prostate Cancer |

| 1420-1440 | Chris Harding (BJUI sponsored BAUS lecture)

The Mesh Story – lessons learned and future plans |

| 1440-1500 | Nick Watkin

PROMs in Urology |

| 1500-1520 | Stephen Mark

Big Data and Urology – a pilot trial in New Zealand |

| 1520-1540 | Afternoon tea |

|

Education /Training /Innovation – CHAIR: Prokar Dasgupta

|

|

| 1540-1600 | Andrew Hung (BJUI sponsored lecture)

The emerging role of Artificial Intelligence in Surgical Science |

| 1600-1620 | Jonathan Kam

Zero learning curve Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy Access – Prone endoscopic combined intrarenal surgery and multimedia training aid to teach urology trainees |

| 1620-1640 | Madhu Koya (BJUI sponsored USANZ lecture)

Cx bladder reduces flexible cystoscopy in haematura and superficial TCC |

| 1640-1700 | Kamran Ahmad

Innovation in healthcare systems |

| 1700-1705 | BJUI Coffey-Krane Award for trainees based in The Americas presented by Prokar Dasgupta |

| 1700-1900 | BJUI Reception |

Article of the Week: Comparing FG, USG and CG for renal access in mini-PCNL

Every week the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Week from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to the article itself, there is an accompanying editorial written by a prominent member of the urological community. This blog is intended to provoke comment and discussion and we invite you to use the comment tools at the bottom of each post to join the conversation.

Finally, the third post under the Article of the Week heading on the homepage will consist of additional material or media. This week we feature a video discussing the paper.

If you only have time to read one article this week, it should be this one.

A prospective and randomised trial comparing fluoroscopic, total ultrasonographic, and combined guidance for renal access in mini-percutaneous nephrolithotomy

*†, *†, *†, *†, *†, *† Wenzhong Chen*†, *†, *, *†, *†, Ming

Lei*†, *†, *†, *†, *†, *, *†

and *†

*Department of Urology, Minimally Invasive Surgery Center, The First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, and †Guangdong Key Laboratory of Urology, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China

Abstract

Objective

To compare the safety and efficacy of fluoroscopic guidance (FG), total ultrasonographic guidance (USG), and combined ultrasonographic and fluoroscopic guidance (CG) for percutaneous renal access in mini-percutaneous nephrolithotomy (mini-PCNL).

Patients and methods

The present study was conducted between July 2014 and May 2015 as a prospective randomised trial at the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University. In all, 450 consecutive patients with renal stones of >2 cm were randomised to undergo FG, USG, or CG mini-PCNL (150 patients for each group). The primary endpoints were the stone-free rate (SFR) and blood loss (haemoglobin decrease during the operation and transfusion rate). Secondary endpoints included access failure rate, operating time, and complications. S.T.O.N.E. score was used to document the complexity of the renal stones. The study was registered at https://clinicaltrials.gov/ (NCT02266381).

Results

The three groups had similar baseline characteristics. With S.T.O.N.E. scores of 5–6 or 9–13, the SFRs were comparable between the three groups. For S.T.O.N.E. scores of 7–8, FG and CG achieved significantly better SFRs than USG (one-session SFR 85.1% vs 88.5% vs 66.7%, P = 0.006; overall SFR at 3 months postoperatively 89.4% vs 90.2% vs 69.8%, P = 0.002). Multiple-tracts mini-PCNL was used more frequently in the FG and CG groups than in the USG group (20.7% vs 17.1% vs 9.5%, P = 0.028). The mean total radiation exposure time was significantly greater for FG than for CG (47.5 vs 17.9 s, P < 0.001). The USG had zero radiation exposure. There was no significant difference in the haemoglobin decrease, transfusion rate, access failure rate, operating time, nephrostomy drainage time, and hospital stay among the groups. The overall operative complication rates using the Clavien–Dindo grading system were similar between the groups.

Conclusions

Mini-PCNL under USG is as safe and effective as FG or CG in the treatment of simple kidney stones (S.T.O.N.E. scores 5–6) but with no radiation exposure. FG or CG is more effective for patients with S.T.O.N.E. scores of 7–8, where multiple percutaneous tracts may be necessary.

Editorial: Renal access during PCNL: increasing value of USG for a safer and successful procedure

Renal access to the pelvicalyceal system is the initial but highly important and crucial step of percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL), which can significantly affect the final outcome of the procedure. Although the puncture of the kidney and subsequently dilatation of the tract has been commonly performed under fluoroscopic guidance [1]; renal access can also be established under ultrasonographic guidance (USG) with or without fluoroscopy.

To give a further insight into the role of both methods; in a prospective and randomised study published in this issue of the BJUI, Zhu et al. [2] have compared the safety and efficacy of fluoroscopic (FG), total ultrasonographic (USG), and combined ultrasonographic and fluoroscopic guidance (CG) for percutaneous renal access during mini-PCNL (mini-PCNL). In all, 450 consecutive patients with renal stones of >2 cm were randomised to undergo three different approaches during mini-PCNL. In addition to the stone-free rate (SFR) and blood loss as primary endpoints; access failure rate, operative time and complications were also evaluated. The S.T.O.N.E. [stone size (S), tract length (T), obstruction (O), number of involved calices (N), and essence or stone density (E)] scoring system was used for stone assessment [3] and the scores were further categorised into three grades (5–6, 7–8 and 9–13) for comparison.

While the overall operative complication rates, using the Clavien–Dindo grading system, were similar between the three groups; colonic injury treated with a temporary colostomy occurred in one case in the CG group. Although the SFRs were similar between the groups with S.T.O.N.E. scores of 5–6 and 9–13; the FG and CG approaches achieved significantly better SFRs than USG in patients with scores of 7–8, (P = 0.006). Multiple-tracts PCNL were used more frequently in the FG and CG group than USG group (P = 0.028). While the access failure rate was similar in the groups, the mean access time was longer in the CG group than in the FG and USG groups (P = 0.003). However, the mean total radiation exposure time was significantly greater for FG than for CG (47.5 vs 17.9 s, P < 0.001). The USG had zero radiation exposure. The operative time, hospital stay, nephrostomy drainage time, and the changes in the haemoglobin and creatinine levels were all similar in the three groups. The authors [1] concluded that mini-PCNL under total USG is as safe and effective as FG or CG in the treatment of simple kidney stones (S.T.O.N.E. scores 5–6) with no risk of radiation exposure. FG or CG is more effective for patients with S.T.O.N.E. scores of 7–8 where multiple percutaneous tracts may be necessary.

Percutaneous nephrolithotomy is now the preferred treatment method for larger stones (>2 cm) with successful outcomes. However, despite the high SFR obtained in a single session this approach can be associated with some severe complications such as bleeding, organ perforation, and sepsis. Such complications could be encountered during all steps of PCNL among which renal access seems to be the most critical one [4]. An appropriate puncture aiming a direct path from the skin through the papilla of the desired calyx of the kidney is of paramount importance to limit the above mentioned complications. Such an access to the renal collecting system can be established by either FG and/or USG. Although FG has been used commonly in the past; increasing experience in US applications has enabled endourologists to use this approach more often with some certain advantages in preventing renal puncture-related complications. When compared with FG, use of USG in establishing an access under vision allows the surgeon to identify the kidney pelvicalyceal system as well as the surrounding organs in a precise manner [5], with the benefit of minimising the risk of injury to such organs. Moreover, in addition to being free of ionising radiation; USG results in fewer punctures, has shorter operating times, and avoids contrast-related complications [1, 2]. Apart from helping to identify non-opaque residual stones at the end of the procedure; colour Doppler US can be used as a tool to localise the intrarenal arteries and avoid their puncture. However, the use of USG is an operator-dependent procedure requiring sufficient experience before routine performance and it may not be as efficient in the extremely obese patient and patients without hydronephrosis.

For the use of USG access in clinical practice, Agarwal et al. [5] reported a shorter mean time for successful puncture and significantly lower radiation exposure, yielding complete stone clearance with no substantial morbidity when compared with the FG technique. USG access was found also to increase puncture accuracy to a certain extent with a 96.5% SFR in another trial [6].

In conclusion, each of these techniques mentioned above have their own advantages and disadvantages. Despite its high success rate, radiation exposure and risk of multiple punctures are the main risks of the FG approach. USG renal access in experienced hands can produce high success rates following an appropriate puncture, lower risk of radiation exposure, and the ability to monitor all organs in the path of the puncture [7]. Depending on the surgeon’s experience, patient and stone-related factors, as well as the technical infrastructure, each approach may be used either alone or in combination for a complication-free and successful procedure. However, taking the above mentioned advantages of USG access into account, it is clear that all young urologist need to increase their experience in USG puncture to use it in appropriate cases (children, pregnant cases, dilated kidneys etc.) to lower the radiation risk and shorten the procedural duration.

, Professor of Urology, Chief

Department of Urology, Health Sciences University, Dr Lutfi Kirdar Kartal Research and Training Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey

References

1 Michel MS, Trojan L, Rassweiler JJ. Complications in percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Eur Urol 2007; 51: 899–906

2 Zhu W, Li J, Yuan J et al. A prospective and randomised trial comparing fluoroscopic, total ultrasonographic, and combined guidance for renal access in mini-percutaneous nephrolithotomy. BJU Int 2017; 119: 612–8

3 Okhunov Z, Friedlander JI, George AK et al. S.T.O.N.E. nephrolithometry: novel surgical classification system for kidney calculi. Urology 2013; 81: 1154–60

4 Aslam MZ, Thwaini A, Duggan B et al. Urologists versus radiologists made PCNL tracts: the UK experience. Urol Res 2011; 39: 217–21

5 Agarwal M, Agrawal MS, Jaiswal A, Kumar D, Yadav H, Lavania P. Safety and efficacy of ultrasonography as an adjunct to fluoroscopy for renal access in percutaneous nephrolithotomy. BJU Int 2011; 108: 1346–9

6 BasiriA, Ziaee AM, Kianian HR, Mehrabi S, Ka rami H, Moghaddam SM. Ultrasonographic versus flu oroscopic access for percutaneous nephrolithotomy, a randomized clinical trial. J Enodourol 2008; 22: 28 1–4

7 Osman M, Wendt-Nordahl G, Heger K, Michel MS, Alken P, Knoll T. Percutaneous nephrolithotomy with ultrasonography-guided renal access: experience from over 300 cases. BJU Int 2005; 96: 875–8