We present an 82 year old gentleman who developed Fournier’s gangrene as a result of a colovesical fistula secondary to diverticular disease of sigmoid colon.

Authors: Mr. Yao Pey YONG, SHO General Surgery, Doncaster Royal Infirmary.

Mr. Vivek Kumar, Consultant Urology, Doncaster Royal Infirmary

Corresponding Author: Mr. Yao Pey YONG, E:mail: yaopey@doctors.org.uk

Abstract

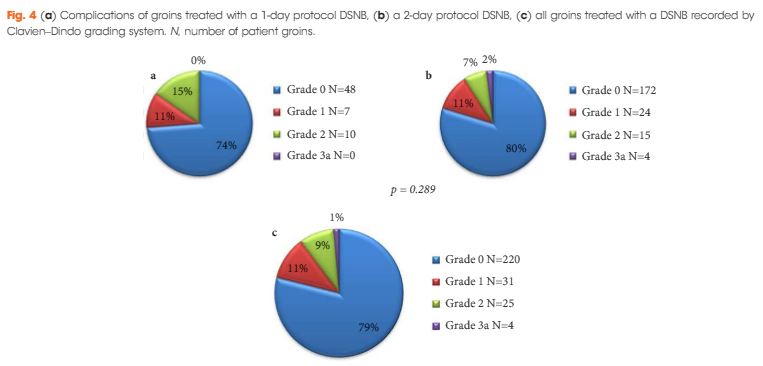

Colovesical fistula has been described as a cause of Fournier’s gangrene but it is a rare occurence. We present an 82 year old gentleman who developed Fournier’s gangrene as a result of a colovesical fistula secondary to diverticular disease of sigmoid colon. The unusual findings during debridement were gangrene of the urethra and testicles. The patient subsequently had a Hartmann’s procedure and closure of the bladder defect. Fournier’s gangrene is a urological emergency that requires a multidisciplinary team approach to optimise patient outcome.

Introduction

Fournier’s gangrene is necrotising fasciitis of the male genitalia. It was first described by Avicenna in 1025 but was named after a French professor in syphilology in 1883 after he described a series of five previously healthy young men suffering from a rapidly progressive gangrene of the penis and scrotum without apparent cause. We present an unusual case of Fournier’s gangrene complicating colovesical fistula secondary to sigmoid diverticulosis, with urethra and bilateral testicular involvement. Although diverticular disease is known to be one of the causes of Fournier’s gangrene, the authors have yet to come across any similar cases in the literature during the writing of this manuscript.

Case Report

An 82 year old gentleman was admitted through the Accident and Emergency Department with a one day history of lower abdominal pain and rigors. His past medical history included osteoarthritis, benign prostatic hypertrophy and colovesical fistula secondary to sigmoid diverticulosis, which was diagnosed one month previously on computerised tomography (CT) scan.

Figure 1. CT scan

He was awaiting elective surgery due a week from the date of admission. His vital signs were as follows: temperature 38°C, blood pressure 120/65mm Hg, heart rate 108/minute, respiratory rate 24/minute and oxygen saturation 98% on room air. Physical examination revealed tenderness across the lower abdomen with minimal voluntary guarding. Initial laboratory studies revealed the following values: haemoglobin 11.1 g/dl, white cell count 7.4 x109/L, C-reactive protein 65.5 mg/L, amylase 54 U/l, creatinine 143 umol/L, urea 12.8 mmol/L, sodium 133 mmol/L and potassium 4.6 mmol/L. Urinalysis revealed protein, leucocytes and nitrites. A diagnosis of acute renal failure and urinary sepsis secondary to colovesical fistula was made. He was fluid resuscitated and commenced on intravenous antibiotics.

On day five of admission, he complained of pain in the perineal region. Physical examination revealed swelling of his penis, scrotum and perineum.

Figure 2. Physical examination

Blood cultures taken on admission revealed an Enterococcus and antibiotics were changed after discussion with the Department of Microbiology. Repeated physical examination the following day revealed patchy necrotic penile skin. A diagnosis of Fournier’s gangrene was made and an immediate urological referral made. Repeated laboratory studies at this point revealed the following values: haemoglobin 8.7 g/dl, white cell count 27.8 x109/L, creatinine 140 umol/L, urea 11.0 mmol/L, sodium 134 mmol/L and potassium 4.1 mmol/L.

The patient had a metabolic acidosis and was fully resuscitated prior to the operation. He underwent four separate operations. The initial procedure was an extensive debridement of perineal, scrotal and penile skin. Surprisingly, deeper structures were involved as well, including the full length of the urethra, and perineal fat. The proximal urethra was ligated. Bowel diversion was deferred due to poor general condition of the patient.

Figure 3. The initial procedure was an extensive debridement of perineal, scrotal and penile skin.

He was brought back to the operating room the next day for further debridement, Hartmann’s procedure, closure of bladder defect and suprapubic cystostomy. He had two further debridements subsequently. Negative pressure wound therapy was applied to the perineal wound (VAC therapy).

Discussion

Fournier’s gangrene is an acute and potentially fatal, deep-seated bacterial infection with secondary necrosis of the skin and soft tissue of the scrotum, perineum and abdominal wall. The infection spreads very rapidly and progressively along the deep fascia.[1] The risk factors include old age, diabetes, alcoholism, malignancy, immunosuppression and any conditions that involve the genitourinary tract or gastrointestinal tract that present potential portals of entry for opportunistic bacteria. A primary source can be identified in 95% of cases.[2] However, Efem[3] argues that Fournier’s gangrene is never idiopathic, and when the cause is not found, it implies that the clinician is unable to determine the cause because the portal of entry may have been so trivial that it was overlooked. In our case, the patient’s risk factors were old age and colovesical fistula secondary to sigmoid diverticulosis.

The symptoms of rigor and discomfort in the external genitalia were initially overshadowed by lower abdominal pain and a positive urinalysis. As the patient had a prior diagnosis of colovesical fistula secondary to diverticulosis, a preliminary diagnosis of lower urinary infection was made on admission. Garcea [4] in his study, showed the most common presenting symptoms of colovesical fistula were pneumaturia (90.1%), faecaluria (76.2%), abdominal pain (70.1%) and recurrent urinary tract infection (66.7%). Diverticulosis is known to be the most common cause of colovesical fistula and occurs mainly in the sixth and seventh decade of life. It is reported that male to female ratio is between 5 to 1 and 1.5 to 1.[5] This is thought to be due to the protective effect of the female reproductive organs as a physical barrier to fistulisation from diseased bowel.[5,6,7] Studies have shown that 50% of women have had a hysterectomy before the development of colovesical fistula. Other causes include Crohn’s disease, malignancy, radiation therapy, trauma and rarely, appendicitis.

The identification and diagnosis of Fournier’s gangrene is challenging in the early stages. Hefny[1] reported only 4 out of 11 patients in his study had a correct preliminary diagnosis. Patients usually present with an insidious onset of pruritis and discomfort in the external genitalia. This is followed by pain, swelling and systemic symptoms including rigors. When gangrene develops, pain may actually subside due to destruction of nerve tissue. The bacteria involved are usually both aerobes and anerobes, with E. coli the predominant aerobe and Bacteroides the predominant anaerobe.[8] They act synergistically with enzymes to invade and destroy fascial planes. As obliterative endarteritis develops, cutaneous and subcutaneous vascular necrosis leads to localised ischemia and further bacterial proliferation.[8] The infection in Colles fascia may spread to the penis and scrotum via Buck’s and Dartos fascia or to the anterior abdominal wall via Scarpa’s fascia. Colles fascia is attached to the perineal body and urogenital diaphragm posteriorly and to the pubic rami laterally, thus limiting progression in these directions.[8] As the infection spreads, induration worsens and bullae are formed. The overlying skin becomes anaesthetised and necrotic at a very late stage.

Fournier’s gangrene is primarily a clinical diagnosis. However, radiological evaluation may aid to reach the diagnosis if in doubt. Plain films are commonly performed and may reveal air in the soft tissue. This is not pathognomonic but nevertheless should alert the clinician to the possibility of necrotising fasciitis.[9] Ultrasonography may be a more useful diagnostic tool as it may show a thickened scrotal wall and peritesticular fluid.[10] Echogenic shadows with ring down artifact represent air, which is the ultrasonographic hallmark of Fournier’s gangrene.[10,11] An infected hydrocoele may mimic Fournier’s gangrene as the testes may be surrounded by fluid. However, no air should be seen in the subcutaneous tissues.[10] CT findings of Fournier’s gangrene include asymmetric fascial thickening, subcutaneous emphysema, fluid collections and abscess formation.[10] Although CT provides higher specificity, ultrasonography is inexpensive and may provide similar findings to those of CT. Magnetic resonance imaging may be used to aid the diagnosis of Fournier’s gangrene, however the evidence is limited.

Textbooks often describe sparing of the testes as their blood supply is directly from the aorta. However, some authors[9,12,13,14] have argued that the incidence of patients requiring orchidectomy for non-viable testes is up to 21%, but in most cases the indications for orchidectomy were pre-existing epididymo-orchitis, scrotal abscess and extensive tissue damage in the surrounding scrotum, groin, and perineal area. Interestingly, Gupta et al[15] did report a case of bilateral testicular gangrene in Fournier’s gangrene. Erke16 stated that the testicular involvement was rare and that when it occurs it indicates a retroperitoneal or intra abdominal source of infection. In our case, the patient had bilateral orchidectomy as the gangrenous tissue was extensive and the testes appeared non-viable. In addition it is unusual to find gangrene of the urethra. In this particular case, the whole of the urethra was gangrenous.

A review done by Elliott et al[17] stated that colostomy was not routinely performed even when the infection involved the perianal area as Fournier’s gangrene can ascend the anterior abdominal wall. Withholding colostomy until the infection has been halted, rather than performing it at initial presentation, may be prudent.[17] Hartmann’s procedure and bladder repair was performed to disconnect the fistula as it was the source of infection in our patient. Although there is limited randomised trials to clarify the role and efficacy of VAC therapy, it appears to be an effective tool for post-operative wound management in Fournier’s gangrene.[18]

Conclusion

Fournier’s gangrene is a potentially fatal, rapidly spreading necrotising soft tissue infection. Clinicians should have a high index of suspicion in patients who carry risk factor(s). Early diagnosis, resuscitation and aggressive debridement are paramount to a favourable outcome.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no competing interests.

References

1. Hefny AF, Eid HO, Al-Hussona M, et al. Necrotising fasciitis: A challenging diagnosis. European Journal of Emergency Medicine 2007;14:50–52.

2. Champion SE. A case of Fournier’s gangrene. Urol Nurse 2007;27:296-299.

3. Efem SE. The features and aetiology of Fournier’s gangrene. Postgrad Med J 1994;70:568-571.

4. Garcea G, Majid I, Sutton CD, et al. Diagnosis and management of colovesical fistulae: Six-year experience of 90 consecutive cases. Colorectal Disease 2006;8:347-352.

5. Hsieh JH, Chen WS, Jiang JK, et al. Enterovesical fistula: 10 year experience. Chin Med J (Taipei) 1997;59:283-8.

6. Abeshouse BS, Robbins MA, Gann M, et al. Intestinovesical fistulas: Report of seven cases and review of the literature. JAMA 1957;164:251-7.

7. Carpenter WS, Allaben RD, Kambouris AA. One-stage resections for colovesical fistulas. J Urol 1972;108:265-7.

8. Marynowski MT, Aronson AA. Fournier Gangrene in Emergency Medicine. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/778866-overview#a0104 (access 27 May 2011)

9. Smith GL, Bunker CB, Dinneen MD. Review: Fournier’s gangrene. British Journal of Urology 1998;81:347-355.

10. Safriel Y, Cohen HL, Torrisi J. Ultrasound Imaging of Scrotal Wall Thickening and Its Significance in the Diagnosis of Fournier’s Gangrene in Older Men. Journal of Diagnostic Medical Sonography 2000;16:29-33.

11. Tsai MJ, Lien CT, Chang WA, et al. Transperineal ultrasonography in the diagnosis of Fournier’s gangrene. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2010;36:387-391.

12. Hejase MJ, Simonin JE, Bihrle R, et al. Genital Fournier’s gangrene: Experience with 38 patients. Urology 1996;47:734-9.

13. Hohenfellner M, Santucci RA. Fournier’s gangrene. In: Heyns CF, Theron PD (Eds.) Emergencies in Urology. Germany: Springer; 2007. p50 – 59.

14. Ayan F, Sunamak O, Paksoy SM, et al. Fournier’s gangrene: A retrospective clinical study of forty one patients. ANZ J Surg 75:1055-1058.

15. Gupta A, Dalela D, Sankhwar SN, et al. Bilateral testicular gangrene: Does it occur in Fournier’s gangrene? Int Urol Nephrol 2007;39:913-915.

16. Eke N. Fournier’s gangrene: A review of 1726 cases. Br J Surg 2000;87(6):718-728.

17. Elliott DC, Kufera JA, Myers RAM. Necrotizing soft tissue infections: Risk factors for mortality and strategies for management. Annals of Surgery 1996;224(5):672-683.

18. Tucci G, Amabile D, Cadeddu F, el al. Fournier’s gangrene wound therapy: Our experience using VAC device. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2009;394:759-760.

Date added to bjui.org: 27/09/2011

DOI: 10.1002/BJUIw-2011-071-web