We report two cases with persistent urinary ascites in the bulbs of pelvic drains post surgical repair for urological complications, which subsided after adjusting the position and suction power of pelvic drains.

Authors: Chen, Kuo-Hu; Chen, Li-Ru; Yang, Bing-Shiang

Corresponding Author: Chen, Kuo-Hu

Kuo-Hu Chen1,2,, MD, PhD, Li-Ru Chen3,4, MD, MSc, Bing-Shiang Yang4, PhD, PE.

1 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Buddhist Tzu-Chi General Hospital, Taipei Branch, Taipei, Taiwan.

2 School of Medicine, Buddhist Tzu-Chi University, Hualien, Taiwan.

3 Mackay Memorial Hospital, Main Branch, Taipei, Taiwan.

4 Department of Mechanical Engineering, National Chiao-Tung University, Taiwan.

Abstract

Pelvic drains and Foley catheters are widely used in the patients that undergo surgical repair for urological complications. However, persistent discharge from the drain tube, an implication of leakage at the site of repair due to the presence of urinary ascites, is a common reason why physicians do not remove the drain tube and Foley catheter. Herein, we report on two cases, where patients presented with urinary ascites after secondary surgery. It is supposed that a close position of the drain tube to the site of repair, as well as excessive suction power of the bulb, may be the primary cause of the persistent discharge, as these would produce a higher negative pressure, and thereby create a “fistula” effect. An attempt of moving the drain tube away from the site of repair and decreasing its suction power by reducing the compression of the bulb was made and appeared to be helpful. We suggest that this cause should be considered and managed in the patients who fail to have a drain removed because of persistent discharge, except the condition of true leakage from the site of repair.

Introduction

Iatrogenic injuries are the most common causes of lower urinary tract trauma. The close proximity of all pelvic organs makes the lower urinary tract susceptible to injury during various types of pelvic surgery [1]. Pelvic drains are often inserted into the body following surgical repairs to adequately remove discharges or bloody ascites produced during these operations, as well as to monitor whether there is any leakage that may have gone unnoticed. However, the pelvic drains themselves may become a primary source of complications that delay recovery.

Case report

Case 1

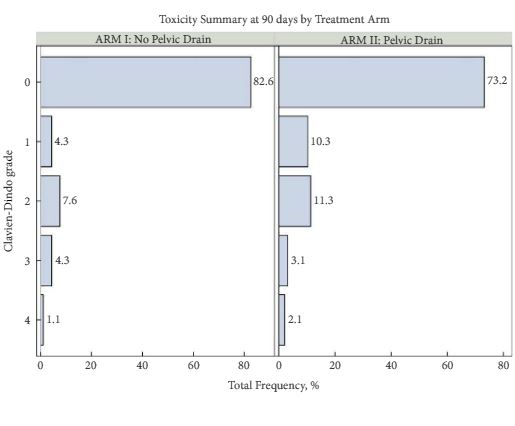

A 49-year-old, parous female was diagnosed with adenomyosis and chronic pelvic inflammation disease. She underwent a laparoscopic hysterectomy, during which severe pelvic adhesion was noted. In the postoperative period, her condition remained stable and she was afebrile. However, abdominal pain, distension, and oliguria developed after surgery. A physical examination found pelvic tenderness, and an abdominal ultrasound revealed pelvic ascites. An intravenous urogram was performed and revealed the findings of ileus, right ureteric obstruction, and hydronephrosis (Figure 1A), which may have resulted from a ureteric injury. Ureteroscopy followed by a laparotomy (including ureteroureterostomy and enterolysis) with an indwelling JJ catheter were arranged and performed meticulously by an experienced urologist one week after the first operation. A Jackson-Pratt (JP) drain was placed into the right pelvis at the end of the operation, and a Foley catheter was inserted into the bladder to ensure adequate decompression of the bladder.

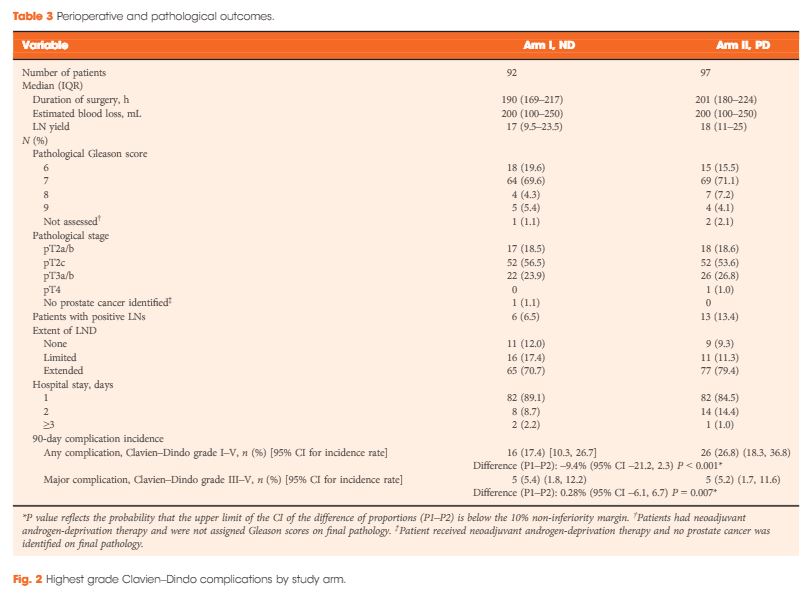

After the second operation, the ileus subsided and the patient’s daily activity increased day by day. She remained afebrile and was able to independently maintain normal daily intake of food and water. Her condition improved, with the exception of the persistent discharge from the JP drain even three weeks after the second surgery, which is suggestive of urinary leakage from the site of repair. The daily amount of discharge from the JP drain decreased in the first two weeks after surgery, but increased in the third week, fluctuating between 30 and 100 mL. The discharge consisted of urinary ascites, as determined via biochemical testing, which revealed the presence of urine with a creatinine level of 22.1 mg/dL. Abdominal computed tomography and a plain abdominal radiograph of the kidney, ureter, and bladder (KUB film) were arranged and disclosed a close position of JP tube to the site of re-anastomosis (Figure 1B). We supposed that the close position of the JP drain tube and excessive suction power of the bulb may be the primary cause of the persisted discharge. Consequently, the tube was pulled out by 5-10 cm and the compression of the suction bulb was decreased by 50-75%. Similar to the method used in Whitson’s study, the suction power of the JP bulb we used (Jackson-Pratt, 100 mL) is gauged with a Mikro-tip catheter pressure transducer system (Millar Instruments, Inc., Houston, TX) by connecting the bulb to the reservoir of water in the pressure system after clamping the end of the drain tube. The negative pressure of the JP bulb was measured with a maximum of –130 mmHg. The “50-75%” reduction in negative pressure was confirmed by connecting the bulb again to the pressure transducer system after adjusting the JP bulb. This attempt at adjusting the position and suction power of the JP drain appeared to be helpful, as the daily amount of drainage decreased, and two weeks after, there was no drainage at all. The patient was then discharged after the removal of both the JP drain and Foley catheter, and she did not present with any sequelae at the follow-up appointment.

Case 2

A 34-year-old woman was diagnosed with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus in 2009. Her medical history included two caesarean sections, a right tubo-ovarian abscess, post-right salpingo-oophorectomy and pelvic adhesiolysis. She had suffered from persistent low abdominal pain, and was hospitalized because of a left tubo-ovarian abscess with sepsis. Prior to admission, her WBC count and CRP levels were 19,200/mL and 25.5 mg/dL, respectively.

The patient underwent an emergency laparoscopic left partial salpingo-oophorectomy and drainage of abdominal abscess. A bladder rupture with a laceration of 2 cm in diameter was noted during this operation, and it was laparoscopically repaired by cystorrhaphy with 2-0 vicryl. A culture of the pus in the abscess yielded mixed bacterial and yeast growth, including Candida albicans. After surgery, her diabetes mellitus was controlled with oral hypoglycemic agents, and her infection was treated by administration of intravenous antibiotics. A JP drain was placed into the lower pelvis at the end of the surgery, and a large French Foley catheter was inserted to ensure decompression of the bladder.

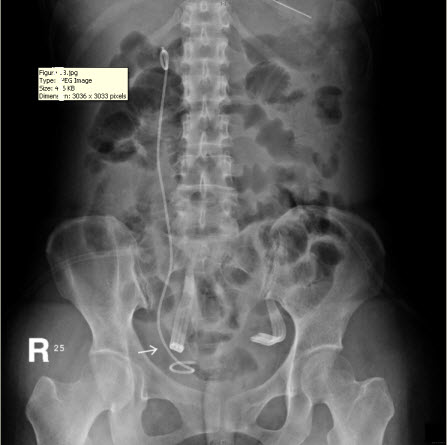

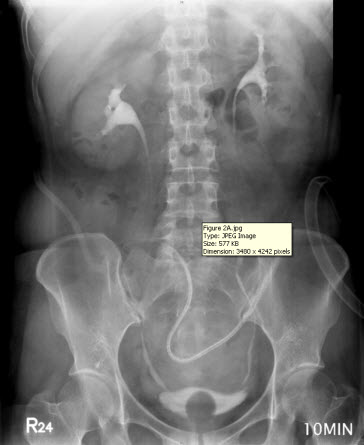

The discharge from the JP drain decreased after the surgery. When the daily amount of discharge was less than 5 mL (near zero) for five more days, an intravenous urogram was performed and showed an intact urinary tract (Figure 2A). She began to undergo Foley clamping, and was prepared for the removal of the JP drain and Foley catheter. Unfortunately, the discharge from the JP drain increased to 300 mL per day, and it was confirmed that there was the presence of urinary ascites, a sign of poor healing at the repair site of the bladder. A cystogram revealed contrast medium leakage in the left anterior aspect of the urinary bladder (near the bladder dome), and that the JP tube was close to the site of repair (Figure 2B). Based on our previous successful experience, the JP tube was pulled out by 5-10 cm and the compression of the suction bulb was decreased by 50-75%. Her condition improved, and the daily amount of discharge from the JP drain began to decrease until there was less than 5 mL being discharged for more than 10 days. Another cystogram was performed and revealed an intact urinary tract without any leakage from the site of repair. Subsequently, the patient had the Foley catheter removed, and was able to void from her bladder. Following the removal of the Foley catheter, there was no discharge from the JP drain, which was then removed on the next day. The patient was in a stable condition and discharged. She did not present with any sequelae on follow-up.

Discussion

Many types of drains, including Penrose, Surgidyne, Jackson-Pratt, and Hemovac, are used in a variety of surgeries for different purposes [2]. Of these, the JP bulb has demonstrated medium suction power and volume collection [3]. The drains are inserted into the body following major surgery for different purposes, such as to adequately remove discharges or bloody ascites produced during these operations, or to monitor whether any injury occurs and may have gone unnoticed. Nevertheless, the drains themselves can become a primary source of complications that delay recovery.

Gynaecological operations are the major causes of iatrogenic injuries in the urinary tract [4]. Some patients may experience symptoms of incontinence [5], which are due to the development of ureterovaginal or vesicovaginal fistulas, or may present with massive urinary ascites [6,7], if the injury is not found and managed. Current evidence suggests that repair by laparoscopic surgery [8-10] and repair at an earlier stage [11] are feasible, if surgical intervention is considered. Pelvic drains are commonly used after surgical repair of iatrogenic injuries. However, persistent discharge observed at bedside, which may imply leakage from the site of re-anastomosis, is often confusing to clinicians, and consequently, they hesitate to remove the pelvic drains. We suppose that the high negative pressure resulting from the close position of the tube to the repair site and the strong suction power of the bulb creates a “fistula” effect between the drain and the site of repair, thereby preventing the tissues from healing appropriately. Thus, the negative pressure that is usually beneficial in the reconstruction of tissues at other times may inversely bring about negative consequences by breaking down the healing tissues.

To our best knowledge, this is the only report to demonstrate the effects of the position of drain tubes and suction power of the bulbs on the healing of the repair site. A literature review via PubMed reveals only one article that reports on a relatively similar concept. Specifically, it was reported that intermittent clamping of suction drains following a total hip replacement reduces postoperative blood loss [12]. However, there are no specific explanations for the motivation and for the observations made in the present study. Nonetheless, our experience provides evidence that persistent urinary leakage from the site of re-anastomosis, despite meticulous repair, can be improved by adjusting the position of the drain tubes and suction power of the bulbs. By doing so, the potential “fistula effect” can be eliminated, thereby improving healing by providing a dry environment, other than the consideration of preventing infection and controlling the underlying medical disorder in general wound care.

Conclusion

The presence of persistent urinary ascites in the bulbs of pelvic drains following surgical repair of urological complications can be reduced by adjusting the position and suction power of the pelvic drain.

References

1. Wagner JR, Russo P. Urologic complications of major pelvic surgery. Semin Surg Oncol. 2000;18(3):216-28.

2. Durai R, Ng PC. Surgical vacuum drains: types, uses, and complications. AORN J. 2010;91(2):266-71.

3. Whitson BA, Richardson E, Iaizzo PA, Hess DJ. Not every bulb is a rose: a functional comparison of bulb suction devices. J Surg Res. 2009;156(2):270-3.

4. Brandes S, Coburn M, Armenakas N, McAninch J. Diagnosis and management of ureteric injury: an evidence-based analysis. BJU Int. 2004;94(3):277-89.

5. Mandal AK, Sharma SK, Vaidyanathan S, Goswami AK. Ureterovaginal fistula: summary of 18 years’ experience. Br J Urol. 1990;65(5):453-6.

6. Hassan I, López C, Gee H, Toozs-Hobson P. Urinary ascites following caesarean section: an unusual presentation of bladder injury. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;147(2):237-8.

7. White V, Hardwick RH, Rees JR, Slack M. Massive urinary ascites after removal of a supra-pubic catheter: case report and review of the literature. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18(7):831-3.

8. Asimakopoulos AD, D’Orazio A, Pereira CF, et al. Surgery illustrated–focus on details: laparoscopic repair of obstructing retrocaval ureter. BJU Int. 2011;107(8):1330-4.

9. Taskin O, Wheeler JM. Laparoscopic repair of bladder injury and laceration. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1995;2(2):227-9.

10. Dalessandri KM, Bhoyrul S, Mulvihill SJ. Laparoscopic hernia repair and bladder injury. JSLS. 2001;5(2):175-7.

11. Badenoch DF, Tiptaft RC, Thakar DR, Fowler CG, Blandy JP. Early repair of accidental injury to the ureter or bladder following gynaecological surgery. Br J Urol. 1987;59(6):516-8.

12. Brueggemann PM, Tucker JK, Wilson P. Intermittent clamping of suction drains in total hip replacement reduces postoperative blood loss: a randomized, controlled trial. J Arthroplasty. 1999;14(4):470-2.

Figures

Figure 1 A

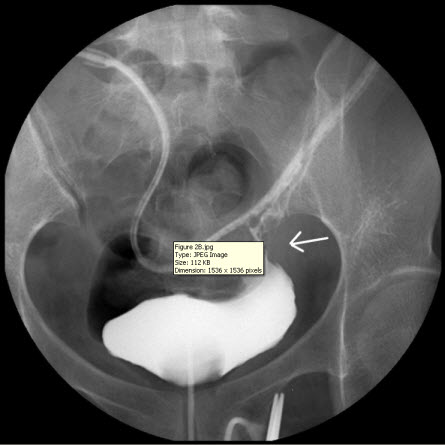

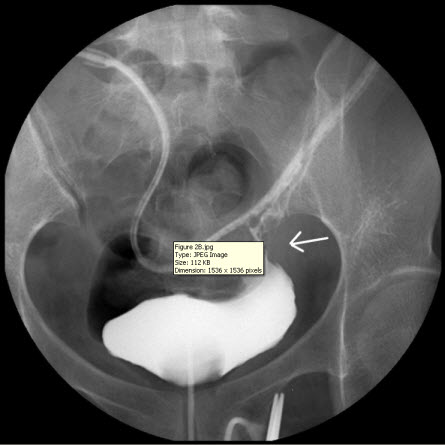

Figure 1 B

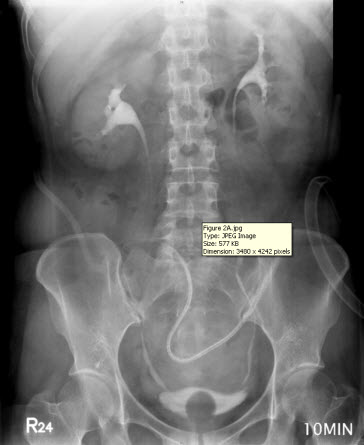

Figure 2 A

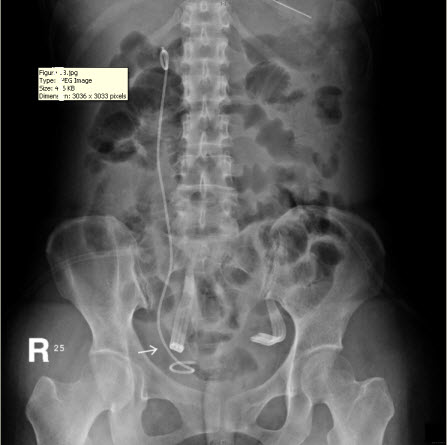

Figure 2 B

Figure Legends

Figure 1: (A) Intravenous urogram revealing ileus, right ureteral obstruction, and hydronephrosis. (B) Plain film of kidney, ureter, and bladder (KUB) revealing the close position of the JP tube to the site of re-anastomosis (arrow), which may be a primary cause of persistent discharge by producing a higher negative pressure, and thereby creating a “fistula” effect.

Figure 2: (A) Intravenous urogram showing an intact urinary tract. (B) A cystogram revealing contrast medium leakage in the left anterior aspect of the urinary bladder (near the bladder dome), and a JP tube close to the site of repair (arrow), which may be a primary cause of persistent discharge by producing a higher negative pressure, and thereby creating a “fistula” effect.

Date added to bjui.org: 27/10/2012

DOI: 10.1002/BJUIw-2012-021-web