Headline news: “Doctors and nurses may face jail for neglect”?

It has been an important few weeks in for doctors in the United Kingdom, sensationalist headlines have been on the front pages of many of the national newspapers: “Doctors and nurses may face jail for neglect”

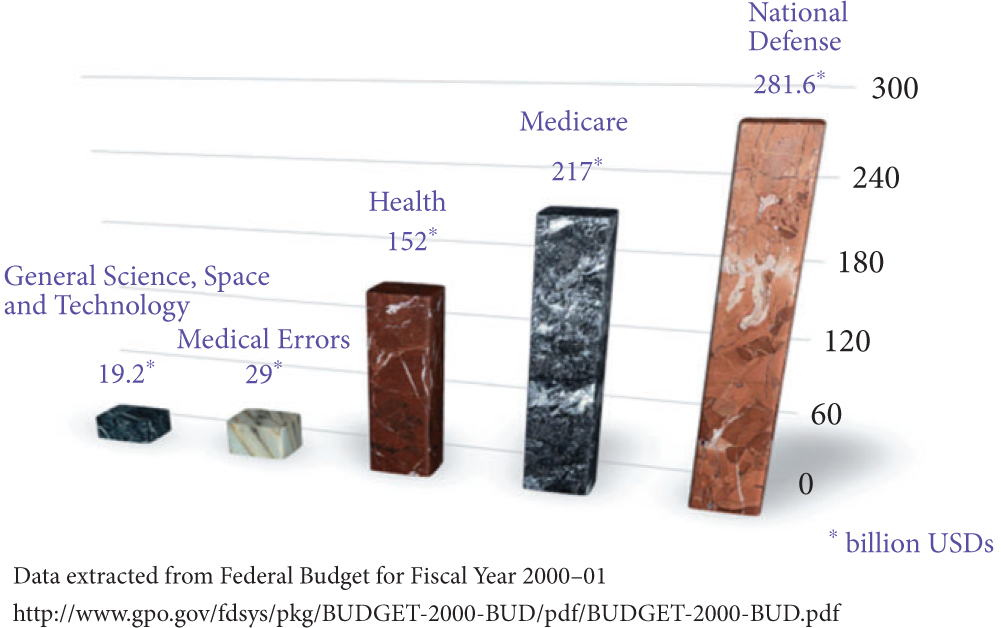

This has all stemmed for the publication of the Francis report and Berwick review into patient safety. They detail recommendations on how the National Health Service (NHS) can learn and improve the standard of patient safety. The Berwick report was led by Professor Don Berwick, an international expert and former adviser to US president Barack Obama, in patient safety. He was asked by the British Prime Minister David Cameron to carry out the review following the publication of the Francis Report into the breakdown of care at a Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Hospital.

Stafford Hospital is an NHS hospital in the West Midlands area of England where hundreds of hospital patients died as a result of substandard care and staff failings between January 2005 and March 2009. The Mid Staffordshire Trust failed to provide safe care in the wards, people lay starving, thirsty and in soiled bedclothes. Decisions about which patients to treat were left to receptionists, inexperienced junior doctors were put in charge of critically-ill patients, and nurses switched off equipment because they did not know how to use it. The culture of the hospital Trust was one of secrecy and defensiveness. The inquiry highlights a whole system failure.

Both reports highlight the main problems affecting patient safety in some hospitals in the NHS and makes recommendations on how to address them. It says that the health system must, amongst many things, recognise the need for wide systemic change by abandoning blame as a tool and trust the goodwill and good intentions of the staff. The use of quantitative targets must be approached with caution and they should never displace the primary goal of better care.

The main headline grabbing item was the recommendation that the UK Government should create a new general offence of willful or reckless neglect or mistreatment applicable both to organisations and individuals.

Organisational sanctions might involve removal of the organisation’s leaders and their disqualification from future leadership roles, public reprimand of the organisation and, in extremis, financial sanctions but only where that will not compromise patient care.

Individual sanctions should be on a par with those in Section 44 of the Mental Health Capacity Act 2005 in UK law, which states that a person can be found guilty of an offence if he ill-treats or willfully neglects a person who lacks capacity and if convicted could be sentenced to imprisonment for a term not exceeding 5 years or a fine or both.

So does this affect us as urologists?

As doctors our first duty of care is towards our patients and patient safety should be our number one priority. However, in light of the report there is the possibility of a custodial sentence to individual(s) where the standard of care falls far short of expectations and blatant neglect is proven. In the age of clinical teams, proving that one individual was at fault is very difficult.

There has been a recent case in the UK press in which a surgeon has been jailed for two and a half years for manslaughter for gross negligence of a patient.

In another case in Australia a 63-year-old American surgeon working in a hospital in Queensland faced complaints from hospital staff that he had botched operations, misdiagnosed patients and used poor surgical techniques. He was arrested in the US in 2008 and extradited to Australia to stand trial. He was jailed for seven years in 2010 after being convicted of criminal negligence leading to the deaths of three patients.

These are two isolated cases but both demonstrate that the days when problematic surgeons were quietly retired are over. Our actions will be scrutinised by an ever demanding public with complications not just being discussed in mortality and morbidity meetings locally but in some cases publicly and in extreme situations in the courts.

My question to the readers is: what happens to clinical staff in your individual countries when clinical negligence and neglect is accused? Is jail time a possibility if proven?

Jonathan Makanjuola is a Urology Trainee, Innovator and techie based at King’s College Hospital, London, United Kingdom. @jonmakUrology