Article of the week: Suture techniques during laparoscopic and robot‐assisted partial nephrectomy

Every week, the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Week from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to the article itself, there is a video produced by the authors. Please use the tools at the bottom of the post if you would like to make a comment.

If you only have time to read one article this week, it should be this one.

Suture techniques during laparoscopic and robot‐assisted partial nephrectomy: a systematic review and quantitative synthesis of peri‐operative outcomes

Abstract

Objective

To summarize the available evidence on renorrhaphy techniques and to assess their impact on peri‐operative outcomes after minimally invasive partial nephrectomy (MIPN).

Materials and Methods

A systematic review of the literature was performed in January 2018 without time restrictions, using MEDLINE, Cochrane and Web of Science databases according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses statement recommendations. Studies providing sufficient details on renorrhaphy techniques during laparoscopic or robot‐assisted partial nephrectomy and comparative studies focused on peri‐operative outcomes were included in qualitative and quantitative analyses, respectively.

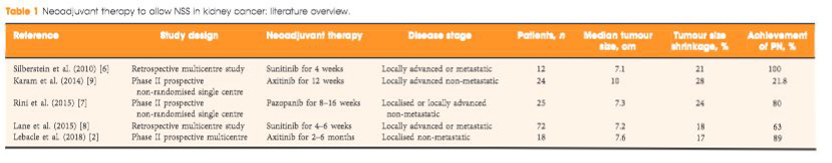

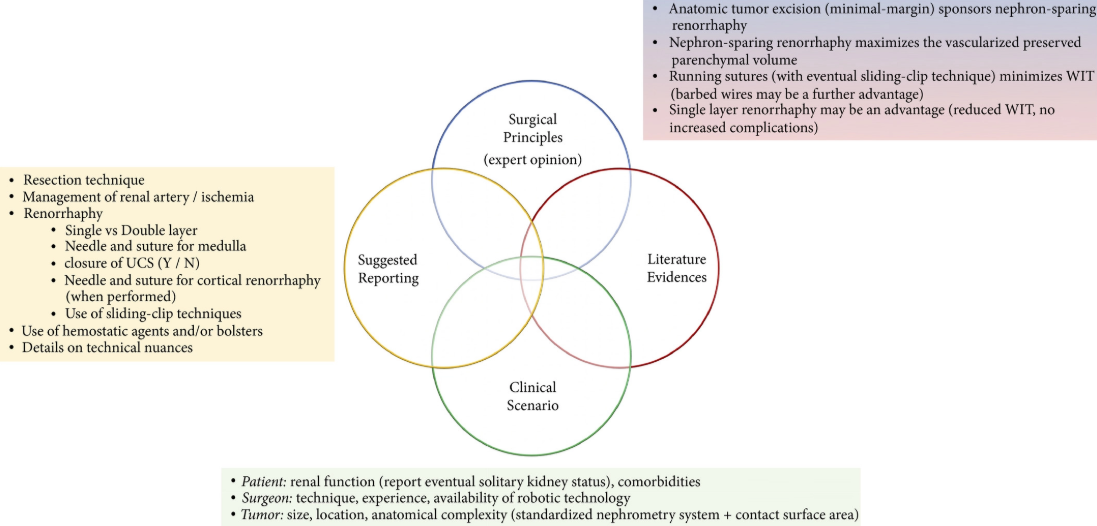

Fig. 4. Integrated overview of evidence‐based technical principles for renal reconstruction during minimally invasive partial nephrectomy and suggested standardized reporting of key renorrhaphy features in clinical studies on this topic.

Results

Overall, 67 and 19 studies were included in the qualitative and quantitative analyses, respectively. The overall quality of evidence was low. Specific tumour features (i.e. size, hilar location, anatomical complexity, nearness to renal sinus and/or urinary collecting system), surgeon’s experience, robot‐assisted technology, as well as the aim of reducing warm ischaemia time and the amount of devascularized renal parenchyma preserved represented the key factors driving the evolution of the renorrhaphy techniques during MIPN over the past decade. Quantitative synthesis showed that running suture was associated with shorter operating and ischaemia time, and lower postoperative complication and transfusion rates than interrupted suture. Barbed suture had lower operating and ischaemia time and less blood loss than non‐barbed suture. The single‐layer suture technique was associated with shorter operating and ischaemia time than the double‐layer technique. No comparisons were possible concerning renal functional outcomes because of non‐homogeneous data reporting.

Conclusions

Renorrhaphy techniques significantly evolved over the years, improving outcomes. Running suture, particularly using barbed wires, shortened the operating and ischaemia times. A further advantage could derive from avoiding a double‐layer suture.