Article of the Week: Occupational variation in the incidence of testicular cancer in the Nordic countries

Every Week, the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Week from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to the article itself, there is an accompanying editorial written by a prominent member of the urological community. This blog is intended to provoke comment and discussion and we invite you to use the comment tools at the bottom of each post to join the conversation.

If you only have time to read one article this week, it should be this one.

Time trends and occupational variation in the incidence of testicular cancer in the Nordic countries

*South-Karelian Central Hospital, University Hospital of Turku, Lappeenranta, Finland, †Department of Oncology, ¶Department of Urology, University Hospital of Turku, Turku, Finland, ‡School of Health Sciences, University of Tampere, Tampere, Finland and §Finnish Cancer Registry, Helsinki, Finland

Abstract

Objective

To describe the trends and occupational variation in the incidence of testicular cancer in the Nordic countries utilising national cancer registries, NORDCAN (NORDCAN project/database presents the incidence, mortality, prevalence and survival from >50 cancers in the Nordic countries) and NOCCA (Nordic Occupational Cancer) databases.

Patients and Methods

We obtained the incidence data of testicular cancer for 5‐year periods from 1960–1964 to 2000–2014 and for 5‐year age‐groups from the NORDCAN database. Morphological data on incident cases of seminoma and non‐seminoma were obtained from national cancer registries. Age‐standardised incidence rates (ASR) were calculated per 100 000 person‐years (World Standard). Regression analysis was used to evaluate the annual change in the incidence of testicular cancer in each of the Nordic countries. The risk of testicular cancer in different professions was described based on NOCCA information and expressed as standardised incidence ratios (SIRs)

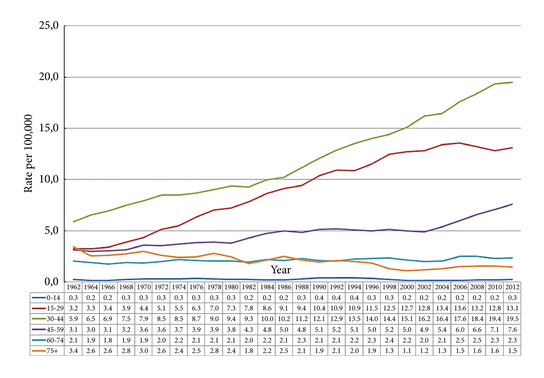

Fig. 2. Testicular cancer incidence time trends by age in the Nordic countries 1960-2014 (5-year floating averages).

Results

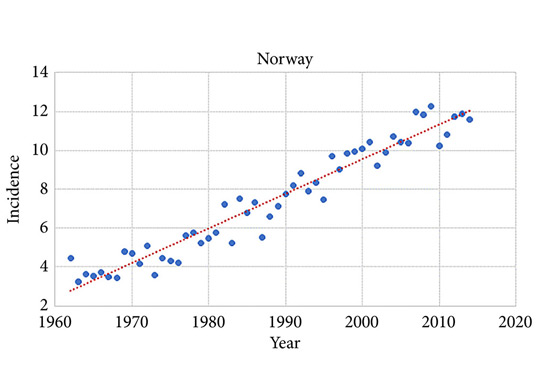

During 2010–2014 the ASR for testicular cancer varied from 11.3 in Norway to 5.8 in Finland. Until 1998, the incidence was highest in Denmark. There has not been an increase in Denmark and Iceland since the 1990s, whilst the incidence is still strongly increasing in Norway, Sweden, and Finland. There were no remarkable changes in the ratio of seminoma and non‐seminoma incidences during the past 50 years. There was no increase in the incidences in children and those of pension age. The highest significant excess risks of testicular seminoma were found in physicians (SIR 1.48, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.07–1.99), artistic workers (SIR 1.47, 95% CI 1.06–1.99) and religious workers etc. (SIR 1.33, 95% CI 1.14–1.56). The lowest SIRs of testicular seminoma were seen amongst cooks and stewards (SIR 0.56, 95% CI 0.29–0.98), and forestry workers (SIR 0.64, 95% CI 0.47–0.86). The occupational category of administrators was the only one with a significantly elevated SIR for testicular non‐seminoma (SIR 1.21, 95% CI 1.04–1.42). The only SIRs significantly <1.0 were seen amongst engine operators (SIR 0.60, 95% CI 0.41–0.84) and public safety workers (SIR 0.67, 95% CI 0.43–0.99).

Conclusions

There have always been differences in the incidence of testicular cancer between the Nordic countries. There is also some divergence in the incidences in different age groups and in the trends of the incidence. The effect of occupation‐related factors on incidence of testicular cancer is only moderate. Our study describes the differences, but provides no explanation for this variation.