Multiparametric MRI (mpMRI) has become an important adjunct in the management of localized prostate cancer (PCa), particularly in the active surveillance (AS) setting. Current guideline recommendations [1,2] have recommended incorporation of mpMRI into AS protocols to improve patient stratification and reclassification.

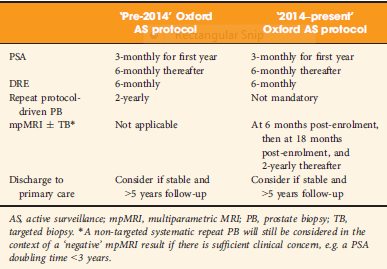

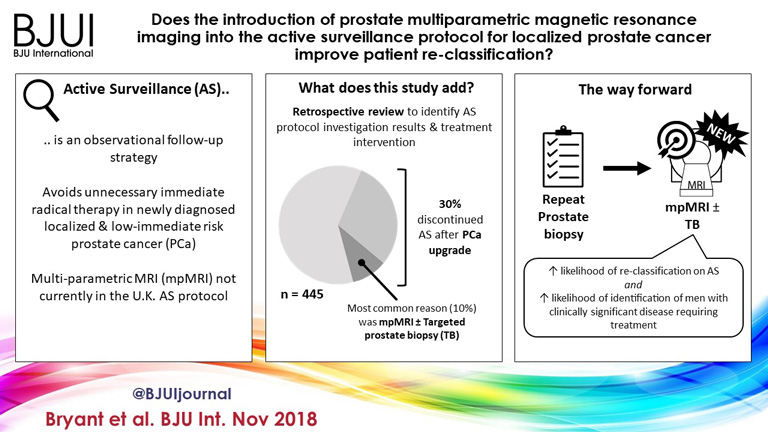

Bryant et al. [3], based on updated National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines [1], report on the effect of mpMRI incorporation into their institution’s AS protocols, specifically focusing on the time to treatment and number of biopsies required to trigger treatment. In 2014, they replaced protocol‐driven biannual prostate biopsies (PBs) with mpMRI ± cognitive targeted biopsy and systematic biopsy (TB). With a median follow‐up of 2.4 years, they found that more men who underwent TB progressed to treatment than men who underwent PB alone (44% vs 37%; P = 0.003). The median number of biopsies (beyond the original diagnostic biopsy) required to trigger intervention was 1.55. Based on these results, the authors conclude that mpMRI‐driven TB increases reclassification compared with protocol‐driven PB.

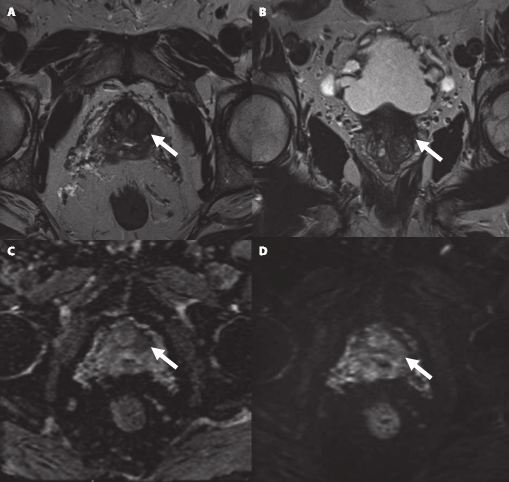

This is consistent with increasing evidence that mpMRI enhances, and sometimes, exceeds detection of clinically significant PCa over TRUS‐guided prostate biopsy alone. The PROMIS study [4], a multicentre paired validation study that compared mpMRI to TRUS‐guided biopsy in the diagnostic setting, found that mpMRI had better sensitivity (93% vs 43%; P < 0.001) and negative predictive value (89% vs 74%; P < 0.001) than TRUS‐guided biopsy in detecting clinically significant cancer (defined as Gleason grade ≥4 + 3). While the concerns about foregoing a systematic biopsy at the time of targeted biopsy in that study were warranted, there was consensus that prebiopsy mpMRI increased the yield for clinically significant PCa.

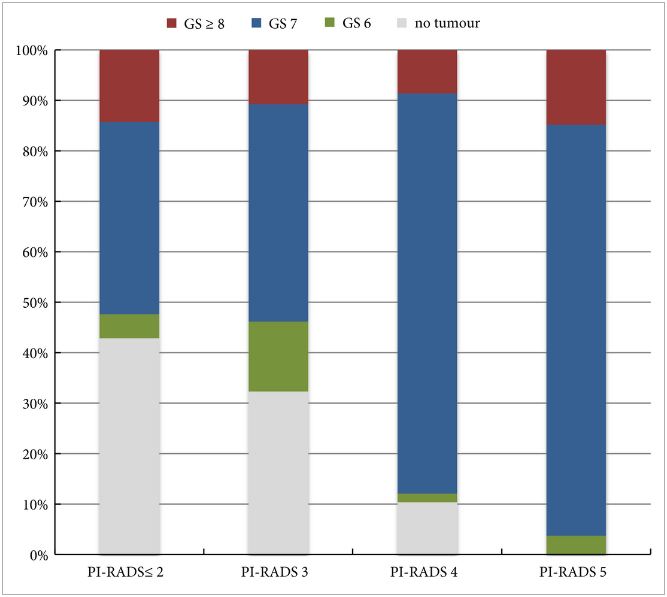

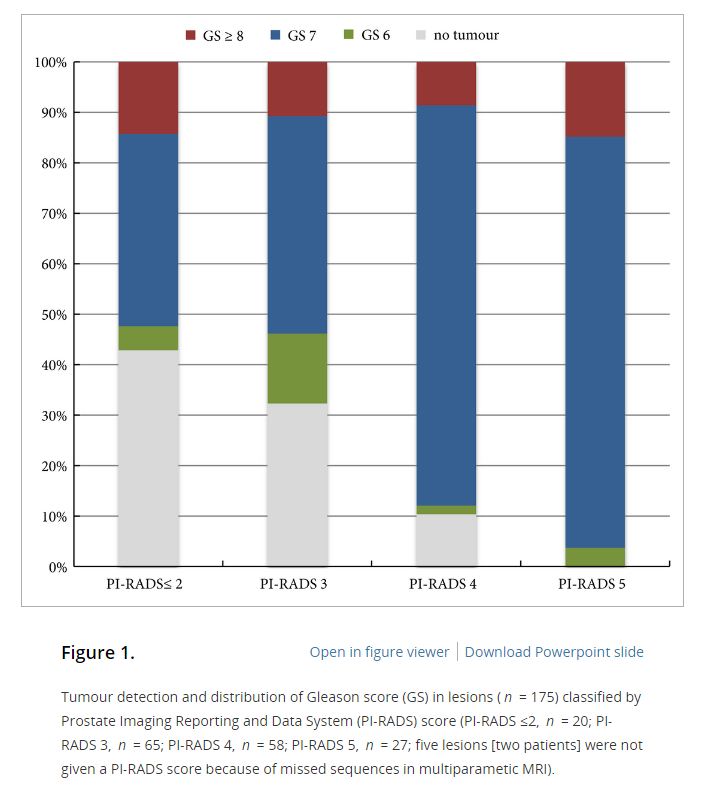

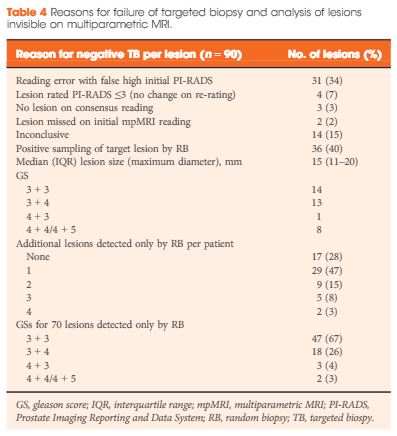

In the AS setting, unfortunately, randomized data are lacking; however, retrospective series and systematic reviews provide some guidance. In a systematic review, Schoots et al. [5] found that a positive mpMRI in the AS setting was associated with a higher risk of upgrading at the time of radical prostatectomy and a higher risk of reclassification at the time of confirmatory biopsy. Yet, a negative mpMRI did not preclude reclassification and upgrading, indicating the continued need for systematic biopsy. Recabal et al. [6] confirmed these conclusions in their retrospective assessment of an institutionally maintained prospective dataset. While MRI‐targeted biopsies detected higher grade cancer in 23% of men, they missed higher grade clinically significant cancers in 17%, 12% and 10% of patients with mpMRI scores of 3, 4 and 5, respectively. This suggests that both targeted and systematic biopsy should be used for the optimal detection of clinically significant PCa in men on AS.

The present study by Bryant et al. [3] reaffirms the value of mpMRI in the AS paradigm. Yet, some concerns about their study cohort and methodology should be noted. First, as the authors clearly note as a limitation, despite completing a targeted and systematic biopsy, all the samples were sent as a single specimen, precluding the ability to distinguish between targeted biopsy and systematic biopsy cores. As the absolute difference in the rate of progression to treatment between the PB and TB arms was only 7%, it is uncertain how much of that was attributable to the addition of targeted biopsy alone.

Additionally, in a closer analysis of their study population, it should be noted that 35% of the patients had Gleason Grade Group 2 disease or higher at the time of inclusion, representing a higher‐risk AS patient population than guideline recommendations. This may account for the higher rate of progression to treatment in this study cohort independent of grade progression – 24% of patients progressed to treatment based on PSA progression alone and an additional 10% were based on mpMRI findings alone.

Lastly, the median number of biopsies required to trigger intervention was 1.55 and, for the majority of patients, this was just one additional biopsy beyond the original diagnostic biopsy. Guideline recommendations indicate the importance of a confirmatory biopsy to exclude Gleason sampling error [2]; however, by definition, many of these patients were essentially upstaged or redirected to active treatment after a confirmatory biopsy. With 59% of the entire AS population never receiving a confirmatory biopsy beyond their original diagnostic biopsy and many progressing to treatment after a confirmatory biopsy, this study population may not reflect a well‐selected low‐risk PCa patient population for AS.

Despite these limitations, the work by Bryant et al. [3] adds to the growing body of evidence supporting the use of mpMRI‐targeted biopsies in addition to systematic biopsy to more accurately risk stratify men for AS, particularly at the time of diagnosis. It remains unknown how we can use mpMRI to individually tailor surveillance strategies or if mpMRI may ultimately replace surveillance biopsies over time.

References

- Graham J, Kirkbride P, Cann K, Hasler E, Prettyjohns M. Prostate cancer: summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2014; 348: f7524

- Mottet N, Bellmunt J, Bolla M et al. EAU‐ESTRO‐SIOG Guidelines on Prostate Cancer. Part 1: screening, diagnosis, and local treatment with curative intent. Eur Urol 2017; 71: 618–29

-

-

-

-