Posts

Article of the week: mpMRI and fusion‐guided biopsies to select and follow African‐American men on active surveillance

Every week, the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Week from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to the article itself, there is an editorial written by a prominent member of the urological community and a video prepared by the authors. These are intended to provoke comment and discussion and we invite you to use the comment tools at the bottom of each post to join the conversation.

If you only have time to read one article this week, it should be this one.

Use of multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging and fusion‐guided biopsies to properly select and follow African‐American men on active surveillance

Jonathan B. Bloom*, Amir H. Lebastchi*, Samuel A. Gold*, Graham R. Hale*, Thomas Sanford*†, Sherif Mehralivand*†‡, Michael Ahdoot*, Kareem N. Rayn*, Marcin Czarniecki†, Clayton Smith†, Vladimir Valera*, Bradford J. Wood§, Maria J. Merino¶, Peter L. Choyke†, Howard L. Parnes**, Baris Turkbey† and Peter A. Pinto*§

*Urologic Oncology Branch, †Molecular Imaging Program, NCI, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA, ‡Department of Urology and Pediatric Urology, University Medical Center Mainz, Mainz, Germany, §Center for Interventional Oncology, ¶Laboratory of Pathology, and **Division of Cancer Prevention, NCI, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA

Abstract

Objectives

To determine the rate of Gleason Grade Group (GGG) upgrading in African‐American (AA) men with a prior diagnosis of low‐grade prostate cancer (GGG 1 or GGG 2) on 12‐core systematic biopsy (SB) after multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging (mpMRI) and fusion biopsy (FB); and whether AA men who continued active surveillance (AS) after mpMRI and FB fared differently than a predominantly Caucasian (non‐AA) population.

Patients and methods

A database of men who had undergone mpMRI and FB was queried to determine rates of upgrading by FB amongst men deemed to be AS candidates based on SB prior to referral. After FB, Kaplan–Meier curves were generated for AA men and non‐AA men who then elected AS. The time to GGG upgrading and time continuing AS were compared using the log‐rank test.

Results

AA men referred with GGG 1 disease on previous SB were upgraded to GGG ≥3 by FB more often than non‐AA men, 22.2% vs 12.7% (P = 0.01). A total of 32 AA men and 258 non‐AA men then continued AS, with a median (interquartile range) follow‐up of 39.19 (24.24–56.41) months. The median time to progression was 59.7 and 60.5 months, respectively (P = 0.26). The median time continuing AS was 61.9 months and not reached, respectively (P = 0.80).

Conclusions

AA men were more likely to be upgraded from GGG 1 on SB to GGG ≥3 on initial FB; however, AA and non‐AA men on AS subsequently progressed at similar rates following mpMRI and FB. A greater tendency for SB to underestimate tumour grade in AA men may explain prior studies that have shown AA men to be at higher risk of progression during AS.

Editorial: Fusion‐guided biopsy to guide active surveillance in African‐American men?

This timely and important article by Bloom et al. [1] highlights findings that warrant special attention in an effort to address and reduce racial disparities in low‐risk prostate cancer. At the population level, African‐American (AA) men are 76% more likely to be diagnosed with prostate cancer and 2.2‐times more likely to die from prostate cancer compared with other men in the USA. Emerging evidence suggests that racial disparities in patients diagnosed with advanced stage or higher‐risk disease may be predominantly accounted for by social factors and healthcare access [1,2]. In contrast, there is growing evidence that raises the question of whether disparities in low‐risk disease may be driven by underlying tumour and/or biopsy misclassification differences [2,3,4].

Bloom et al. [1] examined a USA study cohort from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and found that amongst men referred to the NCI with a prior 12‐core systematic biopsy (SB), AA men with Gleason Grade (GG) 1 disease were nearly twice as likely to be upgraded by targeted multiparametric (mp)MRI fusion‐guided biopsy when compared with non‐AA men. These findings are consistent with contemporary data in the USA‐based Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program, where amongst 20 125 men (including 2594 AA men) with clinical National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) low‐risk prostate cancer (GG 1 on biopsy) who underwent radical prostatectomy (RP) from 2010 to 2015, AA men were more likely to have pathological upgrading at the time of RP when compared with non‐AA men (47.3% vs 45.3%; adjusted hazard ratio 1.12, 95% CI 1.03–1.22, P = 0.007; unpublished analysis). Furthermore, the study findings are consistent with prior work that has shown that AA men with NCCN very‐low‐risk disease who underwent RP were more likely to have disease upgrading at RP (27.3% vs 14.4%; P < 0.001), positive surgical margins (9.8% vs 5.9%; P = 0.02), and higher Cancer of the Prostate Risk Assessment Post‐Surgical scoring system (CAPRA‐S) scores [5]; notably these AA men with very‐low‐risk disease also had a distinct zonal distribution of prostate cancer when compared with other men, with anterior tumours that are more difficult to sample by standard 12‐core SB alone [3].

Although low‐grade/risk disease is considered prognostically favourable and can be managed conservatively with active surveillance (AS), racial differences in outcome and zonal distribution of disease observed in favourable‐risk cohorts has led to controversy over the use of AS in AA men. Furthermore, conservative management trials have severely under‐represented patients of African descent. In this setting, most treatment guidelines advise caution when applying AS to AA patients. As such, although AS rates for low‐risk disease have nearly tripled in the USA from 14.5% to 42.1% from 2010 to 2015, there is lower relative uptake of AS for AA men compared with other men, even after adjusting for socioeconomic status, suggesting that providers and patients may be ‘risk‐stratifying’ AA patients with low‐risk disease into a higher‐risk category, and therefore less willing to proceed with AS [6].

Ultimately, the application of AS to AA patients with low‐risk disease will remain controversial and providers will make decisions based on observational data until a representative trial can help answer: (i) whether AA men diagnosed with low‐risk disease who are eligible for AS might be more likely to have distinct aggressive disease features compared with non‐AA men, and (ii) whether there might be strategies, such as guided‐fusion biopsy and/or incorporation of tumour genomics prior to AS, to help identify AA patients with underlying aggressive disease and appropriately select AA men with low‐risk disease for AS protocols.

The most interesting and important result found by Bloom et al. [1] is that amongst men who underwent mpMRI fusion‐guided biopsy after initial diagnosis of low‐risk disease on SB and who ultimately were continued on AS (those who were upgraded at the time of fusion‐guided biopsy became ineligible for AS), AA and non‐AA men had similar progression rates on AS. This result suggests that incorporation of techniques such as mpMRI and fusion biopsy may help better select AA men for AS when compared with standard 12‐core SB. Specifically, MRI guided‐biopsy may reduce disparate misclassification errors by increasing detection of higher grade and more anterior tumours that are more likely to be found in AA men who initially present with low‐risk disease after standard SB. As such, this strategy may represent one mechanism to better select AA men for AS and therefore may be able to reduce disparities in low‐risk disease.

The authors should be applauded for their important work, and this study builds on a growing body of evidence that clearly demonstrates the need for prospective trials examining different diagnostic/prognostic strategies that may reduce disparities in low‐risk disease by more appropriately selecting AA men for AS strategies.

by Brandon A. Mahal (@BrandonMahal)

References

- , , et al. Evaluation of the contribution of demographics, access to health care, treatment, and tumor characteristics to racial differences in survival of advanced prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 2019; 22: 125– 36

- , , , Prostate cancer‐specific mortality across Gleason scores in black vs nonblack men. JAMA 2018; 320: 2479– 81

- , , , , , Pathological examination of radical prostatectomy specimens in men with very low risk disease at biopsy reveals distinct zonal distribution of cancer in black American men. J Urol 2014; 191: 60– 7

- , , Prostate cancer genomic‐risk differences between African‐American and white men across Gleason scores. Eur Urol 2019; 75: 1038– 40

- , , et al. African American men with very low‐risk prostate cancer exhibit adverse oncologic outcomes after radical prostatectomy: should active surveillance still be an option for them? J Clin Oncol 2013; 31: 2991– 7

- , , et al. Active surveillance for low‐risk prostate cancer in black patients. N Engl J Med 2019; 380: 2070– 2

Video: Use of mpMRI and fusion‐guided biopsies to properly select and follow African‐American men on active surveillance

Use of multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging and fusion‐guided biopsies to properly select and follow African‐American men on active surveillance

Abstract

Objectives

To determine the rate of Gleason Grade Group (GGG) upgrading in African‐American (AA) men with a prior diagnosis of low‐grade prostate cancer (GGG 1 or GGG 2) on 12‐core systematic biopsy (SB) after multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging (mpMRI) and fusion biopsy (FB); and whether AA men who continued active surveillance (AS) after mpMRI and FB fared differently than a predominantly Caucasian (non‐AA) population.

Patients and methods

A database of men who had undergone mpMRI and FB was queried to determine rates of upgrading by FB amongst men deemed to be AS candidates based on SB prior to referral. After FB, Kaplan–Meier curves were generated for AA men and non‐AA men who then elected AS. The time to GGG upgrading and time continuing AS were compared using the log‐rank test.

Results

AA men referred with GGG 1 disease on previous SB were upgraded to GGG ≥3 by FB more often than non‐AA men, 22.2% vs 12.7% (P = 0.01). A total of 32 AA men and 258 non‐AA men then continued AS, with a median (interquartile range) follow‐up of 39.19 (24.24–56.41) months. The median time to progression was 59.7 and 60.5 months, respectively (P = 0.26). The median time continuing AS was 61.9 months and not reached, respectively (P = 0.80).

Conclusions

AA men were more likely to be upgraded from GGG 1 on SB to GGG ≥3 on initial FB; however, AA and non‐AA men on AS subsequently progressed at similar rates following mpMRI and FB. A greater tendency for SB to underestimate tumour grade in AA men may explain prior studies that have shown AA men to be at higher risk of progression during AS.

Article of the week: mpMRI and follow‐up to avoid prostate biopsy in 4259 men

Every week, the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Week from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to the article itself, there is an editorial written by a prominent member of the urological community and a video prepared by the authors. These are intended to provoke comment and discussion and we invite you to use the comment tools at the bottom of each post to join the conversation.

If you only have time to read one article this week, it should be this one.

Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging and follow‐up to avoid prostate biopsy in 4259 men

Wulphert Venderink*, Annemarijke van Luijtelaar*, Marloes van der Leest*, Jelle O. Barentsz*, Sjoerd F.M. Jenniskens*, Michiel J.P. Sedelaar†,Christina Hulsbergen-van de Kaa‡, Christiaan G. Overduin* and Jurgen J. Fütterer*

*Department of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine, †Department of Urology, and ‡Department of Pathology, Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, the Netherlands

Abstract

Objective

To determine the proportion of men avoiding biopsy because of negative multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging (mpMRI) findings in a prostate MRI expert centre, and to assess the number of clinically significant prostate cancers (csPCa) detected during follow‐up.

Patients and method

Retrospective study of 4259 consecutive men having mpMRI of the prostate between January 2012 and December 2017, with either a history of previous negative transrectal ultrasonography‐guided biopsy or biopsy naïve. Patients underwent mpMRI in a referral centre. Lesions were classified according to Prostate Imaging Reporting And Data System (PI‐RADS) versions 1 and 2. Negative mpMRI was defined as an index lesion PI‐RADS ≤2. Follow‐up until 13 October 2018 was collected by searching the Dutch Pathology Registry (PALGA). Gleason score ≥3 + 4 was considered csPCa. Kaplan–Meier analysis and univariable logistic regression models were used in the cohort of patients with negative mpMRI and follow‐up.

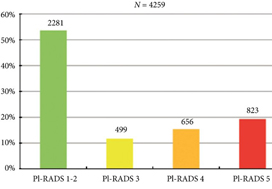

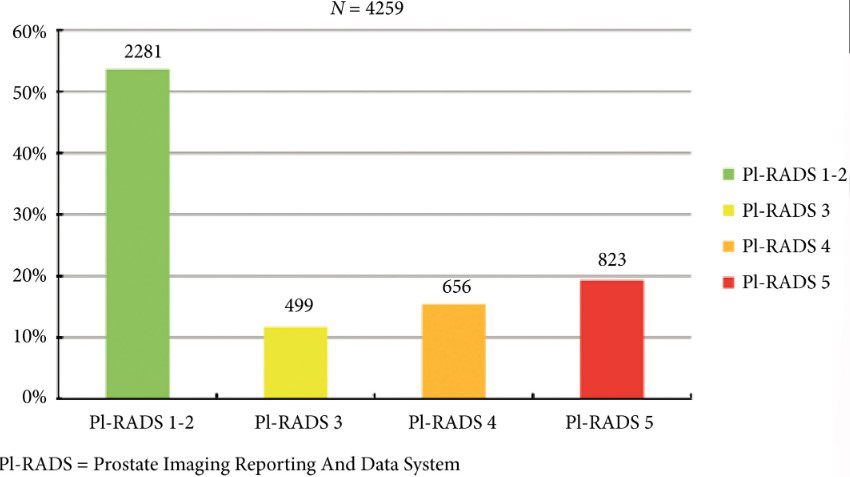

Fig. 2. Distribution of PI‐RADS scored in the entire cohort.

Results

Overall, in 53.6% (2281/4259) of patients had a lesion classified as PI‐RADS ≤2. In 320 patients with PI‐RADS 1 or 2, follow‐up mpMRI was obtained after a median (interquartile range) of 57 (41–63) months. In those patients, csPCa diagnosis‐free survival (DFS) was 99.6% after 3 years. Univariable logistic regression analysis revealed age as a predictor for csPCa during follow‐up (P < 0.05). In biopsied patients, csPCa was detected in 15.8% (19/120), 43.2% (228/528) and 74.5% (483/648) with PI‐RADS 3, 4 and 5, respectively.

Conclusion

More than half of patients having mpMRI of the prostate avoided biopsy. In those patients, csPCa DFS was 99.6% after 3 years.

Editorial: Avoiding biopsy in men with PI‐RADS scores 1 and 2 on mpMRI of the prostate, ready for prime time?

In 2019 is it safe to avoid prostate biopsy in men with Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System (PI‐RADS) score 1 and 2 lesions reported on their multiparametric MRI (mpMRI)? In this journal, Venderink et al. [1] suggest that more than half the men being investigated for suspected prostate cancer could indeed safely avoid an initial biopsy. However, like other investigators in this field, the authors make an assumption in their study that there is such a paucity of clinically significant cancer in men with PI‐RADS 1 and 2 lesions, that biopsy is not deemed necessary, as in the PRECISION study [2]. In this study [1] from the Netherlands, of the 2281 men with an initial diagnosis of PI‐RADS 1 or 2 lesions, only 320 men had follow‐up mpMRI, and biopsies were only performed in a small number of men with PI‐RADS scores ≥ 3. Whilst one could conclude that 84% of men did not progress, based on serial imaging, one cannot prove what may have been missed.

Comparing mpMRI of the prostate to the reference standard of radical prostatectomy whole‐mount specimens, a study from the University of California, Los Angeles showed that mpMRI can potentially miss up to 35% of clinically significant cancers, and up to 20% of high grade cancers. It found that 74% of missed solitary tumours were clinically significant, including 23% with Gleason ≥4 + 3 = 7, and that 38.7% were >1 cm in diameter [3]. As such, these missed cancers were not all small, low grade and clinically insignificant. An Italian study confirmed these findings with a detection rate of clinically significant prostate cancer outside the index lesion seen on mpMRI in 30% of patients [4]. All urologists are aware that biopsy by any means can never detect all the cancers seen on formal whole‐mount histopathology, but we do have evidence using transperineal prostate mapping biopsies as the reference standard as to what may be missed. The PROMIS study [5] provides the best evidence using several definitions of clinically significant cancer. Using Gleason ≥4 + 3 or cancer core length >6 mm the negative predictive value (NPV) of a negative mpMRI was 89%. However, if the criteria were altered to any Gleason 7 cancer, the NPV falls to 76%. This is also supported by a multicentre study by Hansen et al. [6], which demonstrated that the NPV of a negative mpMRI for excluding Gleason 7–10 cancer was 80%, but improved to 91% with a PSA density of <0.1 ng/mL/mL, and to 89% with a PSA density of <0.15 ng/mL/mL. It is important to note that these studies used transperineal biopsies rather than 12‐core transrectal biopsies, suggesting the latter to be a more unreliable reference test with a greater probability of missing clinically significant cancer on systematic sampling.

Are all Gleason 3 + 4 = 7 cancers < 6 mm in core length, for example, 5 mm Gleason 3 + 4 (40%) = 7 cancer, truly clinically insignificant? If that were the case, favourable intermediate‐risk prostate cancer would have to be an accepted indication for active surveillance (AS) in men, and in most cases this is not the case. National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend that men with favourable intermediate‐risk prostate cancer should only be offered AS if the PSA is <10 ng/mL, the lesion is cT1 and the percentage of positive cores is <50%. Prostate Cancer Research International Active Surveillance (PRIAS) criteria only accept men with favourable intermediate‐risk prostate cancer if there is a maximum of two cores involved, PSA density is <0.2 ng/mL/mL, and if it represents <10% of the core. Both European Association of Urology and AUA guidelines caution that if men are offered AS with favourable intermediate‐risk disease, they should be warned of the greater risk of developing metastatic spread. It is therefore clear that major international guidelines do not fully support AS for intermediate‐risk prostate cancers and therefore it may not be acceptable to be missing Gleason 3 + 4 cancers in up to 10–20% of men with normal prostate mpMRI results.

Multiparametric MRI of the prostate has been a huge advance in prostate cancer diagnostics and is now widely used internationally, but does have limitations. Based on the available data, men who choose not to be biopsied with a normal prostate mpMRI should be warned, as part of informed consent, that a clinically significant cancer could be missed in up to 10–20% of cases (depending on PSA density) and close follow‐up should be recommended. One could easily argue that men with normal prostate mpMRI but with PSA density >0.15 ng/mL/mL should still be offered a systematic biopsy. Perhaps the future lies in the genomics of mpMRI‐visible vs ‐invisible lesions, with a recent study showing that there is a confluence of aggressive molecular and pathological features in lesions visible on MRI. Future research may be able to determine if indeed it is safe to leave some Gleason 3 + 4 = 7 cancers undetected if invisible on mpMRI because of their lack of genomic and metabolic aggression rather than based on their Gleason pattern [7].

by Mark Frydenberg

References

- , , et al. Multiparametric MRI and follow up to avoid prostate biopsy in 4259 men. BJU Int 2019; 124: 775– 84

- , , et al. MRI targeted or standard biopsy for prostate cancer diagnosis. N Engl J Med 2018; 378: 1767– 77

- , , et al. Detection of individual prostate cancer foci via multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging. Eur Urol 2019; 75: 712– 20

- , , et al. Association between prostate Imaging Reporting and data system (PIRADS) score for the index lesion and multifocal clinically significant prostate cancer. Eur Urol Oncol 2018; 1: 29– 3336

- , , et al. Diagnostic accuracy of multiparametric MRI and TRUS biopsy in prostate cancer (PROMIS): a paired validating confirmatory study. Lancet 2017; 389: 815– 22

- , , et al. Multicentre evaluation of magnetic resonance imaging supported transperineal prostate biopsy in biopsy naïve men with suspicion of prostate cancer. BJU Int 2018; 122: 40– 9

- , , et al. Molecular hallmarks of multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging visibility in prostate cancer. Eur Urol 2019; 76: 18– 23

Video: mpMRI and follow-up to avoid prostate biopsy in 4259 men

Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging and follow-up to avoid prostate biopsy in 4259 men

Abstract

Objective

To determine the proportion of men avoiding biopsy because of negative multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging (mpMRI) findings in a prostate MRI expert centre, and to assess the number of clinically significant prostate cancers (csPCa) detected during follow‐up.

Patients and methods

Retrospective study of 4259 consecutive men having mpMRI of the prostate between January 2012 and December 2017, with either a history of previous negative transrectal ultrasonography‐guided biopsy or biopsy naïve. Patients underwent mpMRI in a referral centre. Lesions were classified according to Prostate Imaging Reporting And Data System (PI‐RADS) versions 1 and 2. Negative mpMRI was defined as an index lesion PI‐RADS ≤2. Follow‐up until 13 October 2018 was collected by searching the Dutch Pathology Registry (PALGA). Gleason score ≥3 + 4 was considered csPCa. Kaplan–Meier analysis and univariable logistic regression models were used in the cohort of patients with negative mpMRI and follow‐up.

Results

Overall, in 53.6% (2281/4259) of patients had a lesion classified as PI‐RADS ≤2. In 320 patients with PI‐RADS 1 or 2, follow‐up mpMRI was obtained after a median (interquartile range) of 57 (41–63) months. In those patients, csPCa diagnosis‐free survival (DFS) was 99.6% after 3 years. Univariable logistic regression analysis revealed age as a predictor for csPCa during follow‐up (P < 0.05). In biopsied patients, csPCa was detected in 15.8% (19/120), 43.2% (228/528) and 74.5% (483/648) with PI‐RADS 3, 4 and 5, respectively.

Conclusion

More than half of patients having mpMRI of the prostate avoided biopsy. In those patients, csPCa DFS was 99.6% after 3 years.

Editorial: Dropping the GAD – just a fad?

It is not without irony that, at the very moment that the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) is poised to ratify the recommendation that multiparametric MRI (mpMRI) be introduced into the prostate cancer diagnostic pathway, we are seeking to significantly modify the very intervention on which they are about to provide judgement on [1].

The modification proposed is both compelling and plausible, as it renders the process of imaging the prostate in order to detect and localise clinically significant prostate cancer; simpler, quicker, safer and cheaper. It entails dropping the most complex and time‐consuming component of the three multiparametric sequences, the dynamic (time‐dependent) T1‐weighted gadolinium‐enhanced (GAD) sequence. This was a sequence that was, in the early days of MRI, imbued to have biological significance because it was capable of exploiting the differences in the microvascular architecture and function that we have tended to associate with cancer and non‐cancer in order to discriminate between the two. Or so we thought [2].

The systematic review in this issue of the BJUI by Alabousi et al. [3] explores, via the process of systematic review, whether the omission of the T1‐GAD sequence results in any clinically important reduction in test performance when compared with the full sequence scan comprising traditionally of T2, diffusion and T1‐GAD sequences. It did not.

By any stretch this is a tough analysis to pull‐off, as T1‐GAD sequences are not standardised in terms of acquisition or reporting. Every group seems to manage the dynamic images in a different way. As such they tend to suffer from quality control issues, possibly to a greater extent than the T2 and diffusion sequences. The verification of the signal by biopsy strategy and sampling intensity will have varied across studies, as will the threshold of the definition of clinically significant prostate cancer. These inherent methodological problems are all familiar to readers and issues that are pertinent to any imaging study in the detection of prostate cancer. However, there are two issues that make any current assessment of GAD vs no GAD really problematic. The first is the almost exclusive reliance on single‐centre retrospective data. In the few studies that claim a prospective design no comparative data were available. Studies of this type are typical in the early phase of exploring a clinical question and will, in time, be corrected. The other, largely hidden, hardly discussed and truly problematic issue relates to the manner by which we synthesise an overall risk score from the MRI sequences that we derive. The near ubiquitous use of the Prostate Imaging‐Reporting and Data System (PI‐RADS) scoring system introduces a systematic bias by the manner in which a Boolean form of logic is used to decide on the degree of influence that each sequence has in relation to the overall score. According to the manner by which PI‐RADS is applied, it tends to render the T1‐GAD sequence subordinate (only relevant in a minority of cases), contingent (to T2/diffusion) and disparate (dependent on prostate zone) in the way it is invoked [4]. The result is, that within the PIRADS framework, the T1‐GAD sequence is destined to play a relatively small role in driving the overall summary score of risk. It might, therefore, not be too surprising if its removal made little difference to the overall detection of clinically significant prostate cancer.

So what are the next steps? Clearly this is a very important issue and a simpler, quicker, safer and cheaper MRI would be desirable from multiple perspectives. It would render what is currently a complex intervention that comprises an invasive component into a totally passive image acquisition in which no medically trained health professional need be present. It is almost certainly a pre‐requisite for adoption in resource-poor jurisdictions and for entertaining the role of MRI as a primary population‐based screening test.

It took a large number of randomised trials to get mpMRI accepted into the prostate cancer diagnostic pathway. What is the minimum amount of evidence required to disinvest in one of its key components? In other words how many clinically significant cancers would we tolerate missing in order to offer the less complex test?

A direct (head‐to‐head) non‐inferiority randomised comparative study would, following some of our own recent calculations, require >3000 men to participate, which might just prove a little too challenging. An alternative approach is a study in which men would have lesions declared using a Likert score, thereby making no prior assumptions on the role and utility of any single sequence, by traditional mpMRI (standard) but also by a T2‐diffusion MRI (experimental) with appropriate blinding. Some lesions would be private to either standard or experimental imaging but most, it is likely, would be shared. All would require sampling. The yield, the misses, the test accuracy for each approach, could be calculated with necessary adjustments for the inevitable incorporation and verification biases.

It is interesting to observe that in many parts of the world mpMRI was introduced by clinicians before a large body of evidence was accumulated because they felt it was the right thing to do [5]. It may well be the case that ‘dropping the GAD’ will be subject to the same decision‐making process and precede any definitive judgement based on reliable evidence. Recent activity on PubMed would suggest that this might already have happened [6].

References

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Non‐invasive MRI scan for Prostate Cancer recommended by NICE. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/news/article/non-invasive-mri-scan-for-prostate-cancer-recommended-by-nice. Accessed May 2019.

- , , et al. Evaluation of dynamic contrast‐enhanced MRI biomarkers for stratified cancer medicine: how do permeability and perfusion vary between human tumours? Magn Reson Imaging 2018; 46: 98– 105

- , , et al. Biparametric vs multiparametric prostate magnetic resonance imaging for the detection of prostate cancer in treatment‐naïve patients: a diagnostic test accuracy systematic review and meta‐analysis. BJU Int 2019; 124: 209– 20

- , , et al. Prostate Imaging reporting and Data System version 2.1: 2019 update of Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System version 2. Eur Urol 2019 [Epub ahead of print]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2019.02.033

- , , et al. Is it time to consider a role for MRI before prostate biopsy? Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2009; 6: 197– 20

- , , et al. Using biparametric MRI radiomics signature to differentiate between benign and malignant prostate lesions. Eur J Radiol 2019; 114: 38– 44

Video: Biparametric vs multiparametric prostate MRI for the detection of PCa in treatment‐naïve patients: a diagnostic test accuracy systematic review and meta‐analysis

Abstract

Objective

To perform a diagnostic test accuracy (DTA) systematic review and meta‐analysis comparing multiparametric (diffusion‐weighted imaging [DWI], T2‐weighted imaging [T2WI], and dynamic contrast‐enhanced [DCE] imaging) magnetic resonance imaging (mpMRI) and biparametric (DWI and T2WI) MRI (bpMRI) in detecting prostate cancer in treatment‐naïve patients.

Methods

The Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE) and Excerpta Medica dataBASE (EMBASE) were searched to identify relevant studies published after 1 January 2012. Articles underwent title, abstract, and full‐text screening. Inclusion criteria consisted of patients with suspected prostate cancer, bpMRI and/or mpMRI as the index test(s), histopathology as the reference standard, and a DTA outcome measure. Methodological and DTA data were extracted. Risk of bias was assessed using the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS)‐2 tool. DTA metrics were pooled using bivariate random‐effects meta‐analysis. Subgroup analysis was conducted to assess for heterogeneity.

Results

From an initial 3502 studies, 31 studies reporting on 9480 patients (4296 with prostate cancer) met the inclusion criteria for the meta‐analysis; 25 studies reported on mpMRI (7000 patients, 2954 with prostate cancer) and 12 studies reported on bpMRI DTA (2716 patients, 1477 with prostate cancer). Pooled summary statistics demonstrated no significant difference for sensitivity (mpMRI: 86%, 95% confidence interval [CI] 81–90; bpMRI: 90%, 95% CI 83–94) or specificity (mpMRI: 73%, 95% CI 64–81; bpMRI: 70%, 95% CI 42–83). The summary receiver operating characteristic curves were comparable for mpMRI (0.87) and bpMRI (0.90).

Conclusions

No significant difference in DTA was found between mpMRI and bpMRI in diagnosing prostate cancer in treatment‐naïve patients. Study heterogeneity warrants cautious interpretation of the results. With replication of our findings in dedicated validation studies, bpMRI may serve as a faster, cheaper, gadolinium‐free alternative to mpMRI.

Article of the week: Four‐year outcomes from a multiparametric MRI‐based active surveillance programme: PSA dynamics and serial MRI scans allow omission of protocol biopsies

Every week, the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Week from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to the article itself, there is an editorial written by a prominent member of the urological community, and a video made by the authors. These are intended to provoke comment and discussion and we invite you to use the comment tools at the bottom of each post to join the conversation.

If you only have time to read one article this week, it should be this one.

Four‐year outcomes from a multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)‐based active surveillance programme: PSA dynamics and serial MRI scans allow omission of protocol biopsies

Kevin Michael Gallagher*, Edward Christopher*†, Andrew James Cameron*, Scott Little*, Alasdair Innes*, Gill Davis*, Julian Keanie‡, Prasad Bollina* and

Alan McNeill*

*Department of Urology, Western General Hospital, †College of Medicine and Veterinary Medicine, University of Edinburgh, and ‡Department of Radiology, Western General Hospital, Edinburgh, UK

Abstract

Objectives

To report outcomes from a multiparametric (mp) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)‐based active surveillance programme that did not include performing protocol biopsies after the first confirmatory biopsy.

Patients and Methods

All patients diagnosed with Gleason 3 + 3 prostate cancer because of a raised PSA level who underwent mpMRI after diagnosis were included. Patients were recorded in a prospective clinical database and followed up with PSA monitoring and repeat MRI. In patients who remained on active surveillance after the first MRI (with or without confirmatory biopsy), we investigated PSA dynamics for association with subsequent progression. Comparison between first and second MRI scans was undertaken. Outcomes assessed were: progression to radical therapy at first MRI/confirmatory biopsy and progression to radical therapy in those who remained on active surveillance after first MRI.

Results

A total of 211 patients were included, with a median of 4.2 years of follow‐up. The rate of progression to radical therapy was significantly greater at all stages among patients with visible lesions than in those with initially negative MRI (47/125 (37.6%) vs 11/86 (12.8%); odds ratio 4.1 (95% CI 2.0–8.5), P < 0.001). Only 1/56 patients (1.8%) with negative initial MRI scans who underwent a confirmatory systematic biopsy had upgrading to Gleason 3 + 4 disease. PSA velocity was significantly associated with subsequent progression in patients with negative initial MRI (area under the curve 0.85 [95% CI 0.75–0.94]; P <0.001). Patients with high‐risk visible lesions on first MRI who remained on active surveillance had a high risk of subsequent progression 19/76 (25.0%) vs 9/84 (10.7%) for patients with no visible lesions, despite reassuring targeted and systematic confirmatory biopsies and regardless of PSA dynamics.

Conclusion

Men with low‐risk Gleason 3 + 3 prostate cancer on active surveillance can forgo protocol biopsies in favour of MRI and PSA monitoring with selective re‐biopsy.