The prostate cancer pathway is controversial and views are often polarized. For a researcher, this is the perfect melting pot for innovation and practice-changing studies. It is clear that we need to reduce the harms of treatment, not only by treating very few low-risk cancers but also by innovations in surgery. It is pleasing to see Grasso et al. [1] systematic review of surgical innovation that may potentially lead to improvements in urinary incontinence after radical prostatectomy. This was a diligently conducted systematic review and points to the need for a randomized trial, which the authors tell us is currently being conducted.

The prostate cancer pathway is controversial and views are often polarized. For a researcher, this is the perfect melting pot for innovation and practice-changing studies. It is clear that we need to reduce the harms of treatment, not only by treating very few low-risk cancers but also by innovations in surgery. It is pleasing to see Grasso et al. [1] systematic review of surgical innovation that may potentially lead to improvements in urinary incontinence after radical prostatectomy. This was a diligently conducted systematic review and points to the need for a randomized trial, which the authors tell us is currently being conducted.

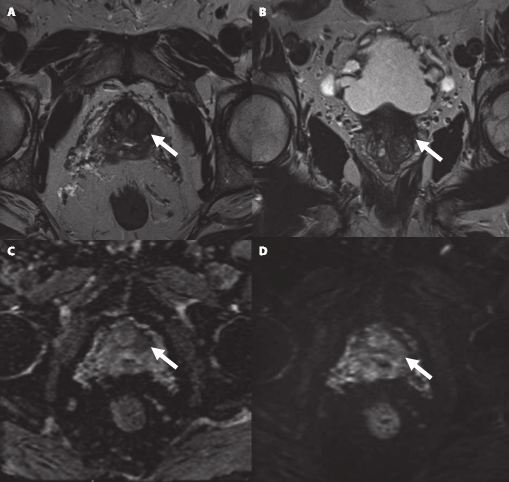

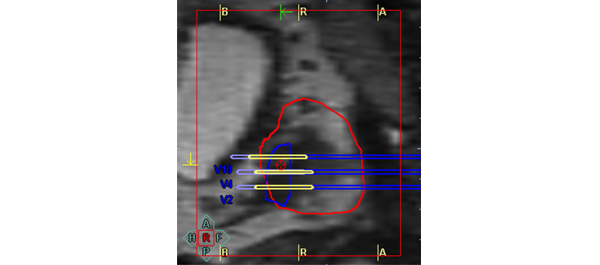

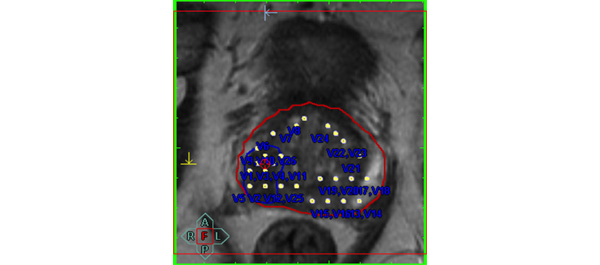

The era of multiparametric MRI (mpMRI) for prostate cancer diagnosis is upon us. Few of us will live through such a wholesale change in the entire pathway for diagnosis and treatment of a cancer, and a common one at that. Whilst a few of us have been using mpMRI prior to first biopsy, there can be no doubting that we now have level 1b evidence to support the adoption of mpMRI prior to a first prostate biopsy as the standard care. The NIHR-HTA/MRC-CTU/UCL PROstate MR Imaging Study (or PROMIS) has been long awaited, and its initial results were presented at ASCO last month [2]. mpMRI performed better than expectations in a multicentre setting across 11 NHS trusts and just over a dozen radiologists. Sensitivity was 93% (95% CI 88–96) and the negative predictive value was 89% (95% CI 83–94). Although the focus, quite rightly, has been on mpMRI, equally significant has been the discovery of how bad a test TRUS-guided biopsy really was, with a sensitivity for clinically significant prostate cancer of only 48% (95% CI 42–55).

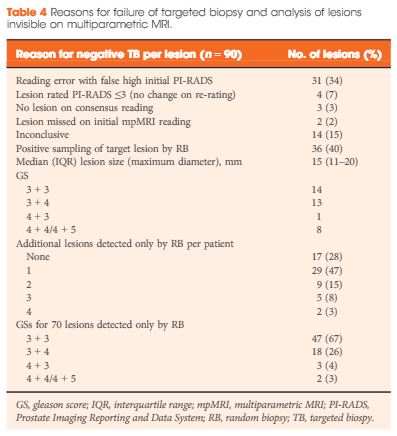

These findings answer several criticisms of mpMRI. First, that it is not as accurate as retrospective data suggest. It is, provided you do not expect it to find every millimetre of significant disease. Second, it is not reproducible outside of expert centres. It is, provided you quality assure every scanner, optimize the sequences iteratively, quality control scans and have robust training for radiologists. Third, it cannot be carried out on 1.5-Tesla scanners. It can; all the PROMIS scans were 1.5 Tesla without an endorectal coil. Fourth, it misses lots of clinically significant prostate cancers. It does not, but this depends on your definition of clinical significance. In this respect, the study by Cash et al. [3] is pertinent. They evaluated the rates of subsequent cancer found on ‘negative’ mpMRIs and, using the very conservative Epstein definition, found a high rate of missed ‘significant’ cancers. The rate of Gleason 7 disease missed was lower and some missed cancers were attributable to interobserver variability in mpMRI reporting. All centres should evaluate their own data to determine where their own negative predictive value sits and then strive to improve upon this through a constant iterative dialogue between urology and radiology. PROMIS shows that mpMRI has very high performance characteristics that should be possible across the board.

There is considerable work still to be done. Cost-effectiveness analyses are under way; with these data, NICE will need to consider their clinical recommendations, having laboured the point that they wished to await PROMIS. The challenge of dissemination and maintenance of quality standards is not to be underestimated. Work on determining what is out there, who is capable of performing such scans and reporting them, whether there is enough capacity in the NHS and whether all centres are capable of carrying out targeted biopsies are all legitimate health policy issues.

Similar to mammography standards laid down centrally, we will need to insist on: independent (not self-) accreditation; independent scan and report audits, with outliers (too many negatives, too many positives, too many equivocals) reviewed to determine whether further standardization training is required; rates of clinically significant and insignificant cancers detected on subsequent biopsy; rates of repeat biopsies; and rates of unnecessary radical therapy on low risk cases. We should all look within our centres to ensure we can meet these expectations.

Hashim U. Ahmed, BJUI Consulting Editor – Imaging Division of Surgery and Interventional Sciences, UCL, and

Department of Urology, UCL Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK

References

1. Grasso AAC, Mistretta FA, Sandri M et al. Posterior musculofascial reconstruction after radical prostatectomy: an updated systematic review and a meta-analysis. BJU Int 2016; 118: 20–34 Wiley Online Library

2. Ahmed HU. The PROMIS study: a paired-cohort, blinded confirmatory study evaluating the accuracy of multi-parametric MRI and TRUS biopsy in men with an elevated PSA. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34: (suppl; abstr 5000)

3. Cash H, Günzel K, Maxeiner A et al. Prostate cancer detection on transrectal ultrasonography-guided random biopsy despite negative real-time magnetic resonance imaging/ ultrasonography fusion-guided targeted biopsy: reasons for targeted biopsy failure. BJU Int 2016; 118: 35–43 Wiley Online Library