PRECISION delivers on the PROMIS of mpMRI in early detection of prostate cancer

Today, Dr Veeru Kasi of University College London, presented the results of the PRECISION (PRostate Evaluation for Clinically Important disease: Sampling using Image-guidance Or Not?) study in the “Game Changing” Plenary session at the #EAU18 Annual Meeting in Copenhagen. The accompanying paper was simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine. And it is stunning! Everyone in the packed eURO auditorium knew they were witness to a practice-changing presentation, and the swift reaction on social media around the world confirms this.

Fundamental paradigm shift in prostate cancer diagnostics, from @veerukasi @mrsprostate #EAU18 today, and @NEJM now online. What a day https://t.co/U7MW3oeCvV pic.twitter.com/MfpgpgGkgV

— Declan Murphy (@declangmurphy) March 19, 2018

PRECISION: MRI-targeted biopsy strategy leads to fewer men needing biopsy. Article with video interviews with Veeru Kasivisvanathan and Declan Murphy https://t.co/QXaWZLaBvo

— European Association of Urology (EAU) (@Uroweb) March 19, 2018

Congratulations to Veeru (a second year urology resident in London), senior author Dr Caroline Moore, Prof Mark Emberton, and all the collaborators on this multicenter international trial. I had the great privilege to be the Discussant in the Plenary session so have been digesting this study in detail for the past few weeks.

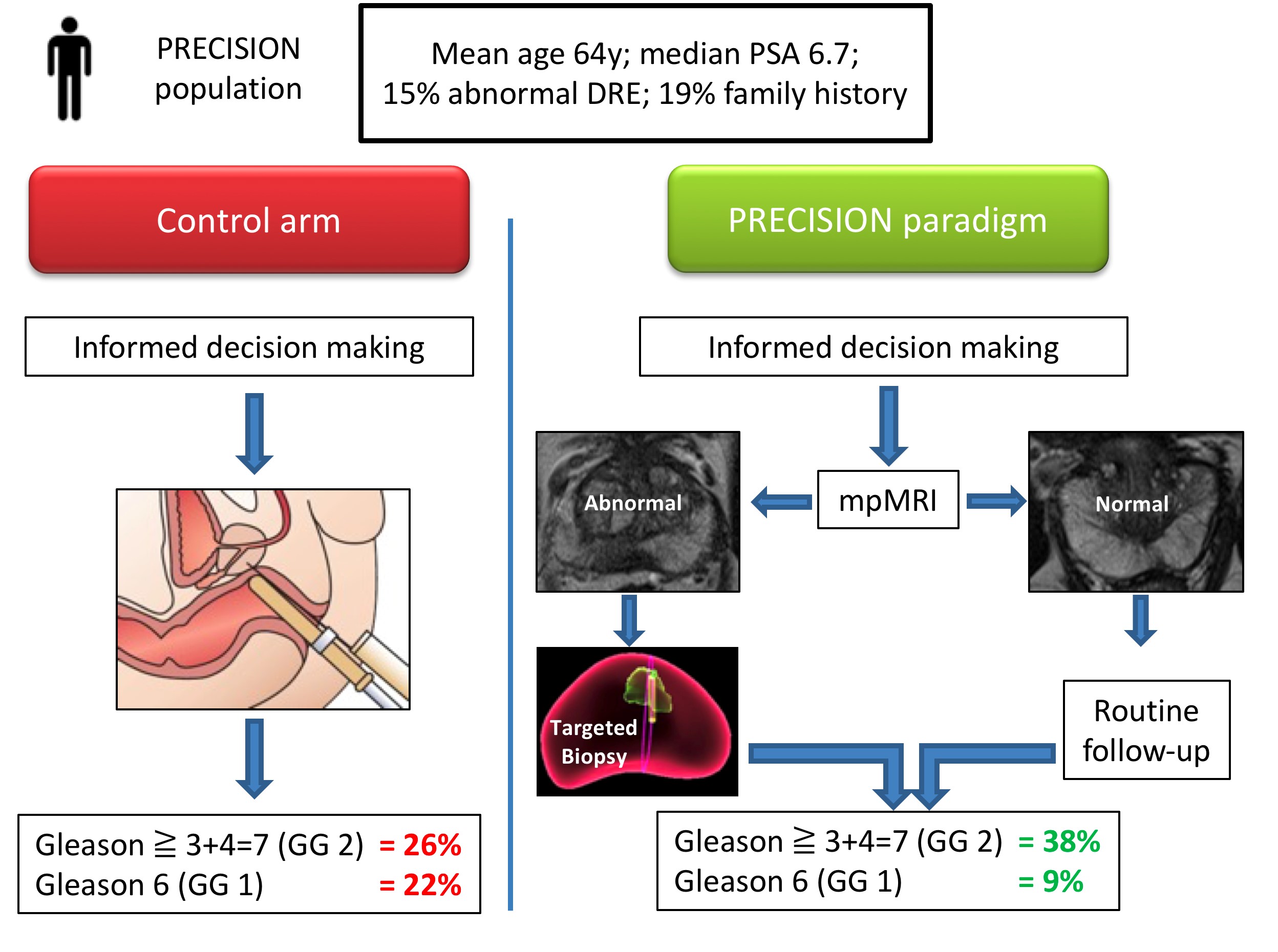

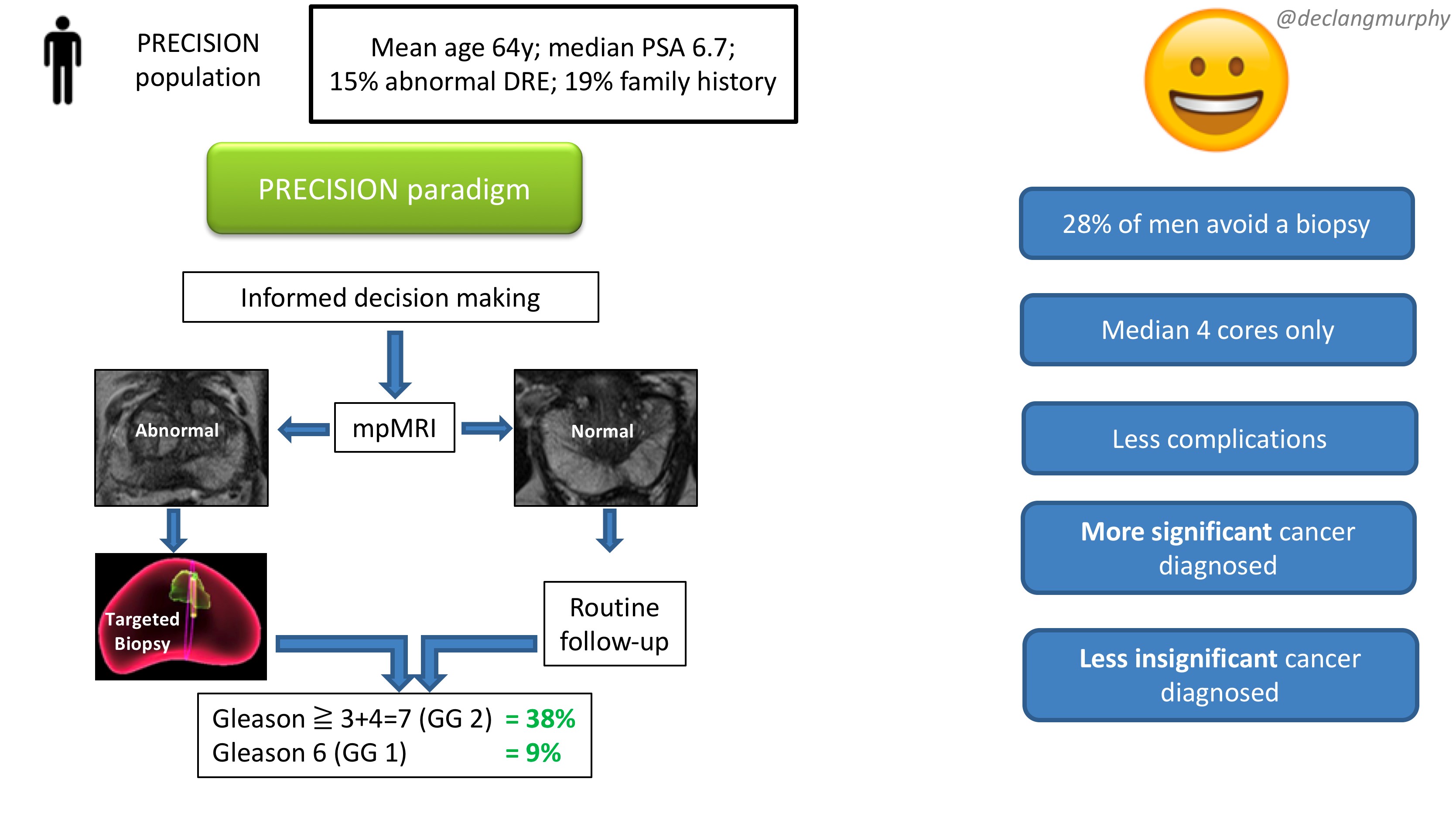

Let me summarise the PRECISION study in brief. In this multicenter international study, 500 men with a suspicion of prostate cancer (mean age 64, median PSA 6.7), were randomised to receive a standard of care (SOC) diagnostic pathway (12 core TRUS biopsy), or an MRI directed pathway. In the MRI pathway, all patients had an MRI, and if the MRI was abnormal (72% of men), they had a targeted biopsy of the lesion(s) (with no systematic biopsy; ie only the abnormal lesion was biopsied). If the MRI was normal (28% of men), they did not have a biopsy, and continued on routine PSA surveillance. The primary outcome was detection rate of clinically significant cancer; and secondary outcomes included the detection rate of clinically insignificant cancer. In the standard of care arm, the detection rate of clinically significant cancer was 26%, and the detection rate of clinically insignificant cancer was 22%. In the MRI pathway, the detection rate of clinically significant cancer was 38%, and the detection rate of taking insignificant cancer was 9%. This is depicted below in one of my summary slides from the plenary discussion.

Therefore, despite the fact that over one quarter of men in the MRI pathway actually avoided a biopsy, the detection rate of clinically significant cancer was much greater in this arm (ie UNDER-diagnosis was reduced). Furthermore, the detection rate of the clinically insignificant cancer was much less (ie OVER-diagnosis was reduced). And all this with a median number of biopsy cores of only four, compared with 12 in the SOC arm. The reduction in core numbers along that too much less complications for these patients.

This looks like WIN-WIN all round!

And I truly believe that these findings should provoke an immediate change in our diagnostic pathway for early prostate cancer in two ways:

- All patients with a clinical suspicion of prostate cancer should be offered an MRI as part of their informed/shared decision making pathway

- All patients with an abnormality on their MRI scan should be offered be targeted biopsy alone.

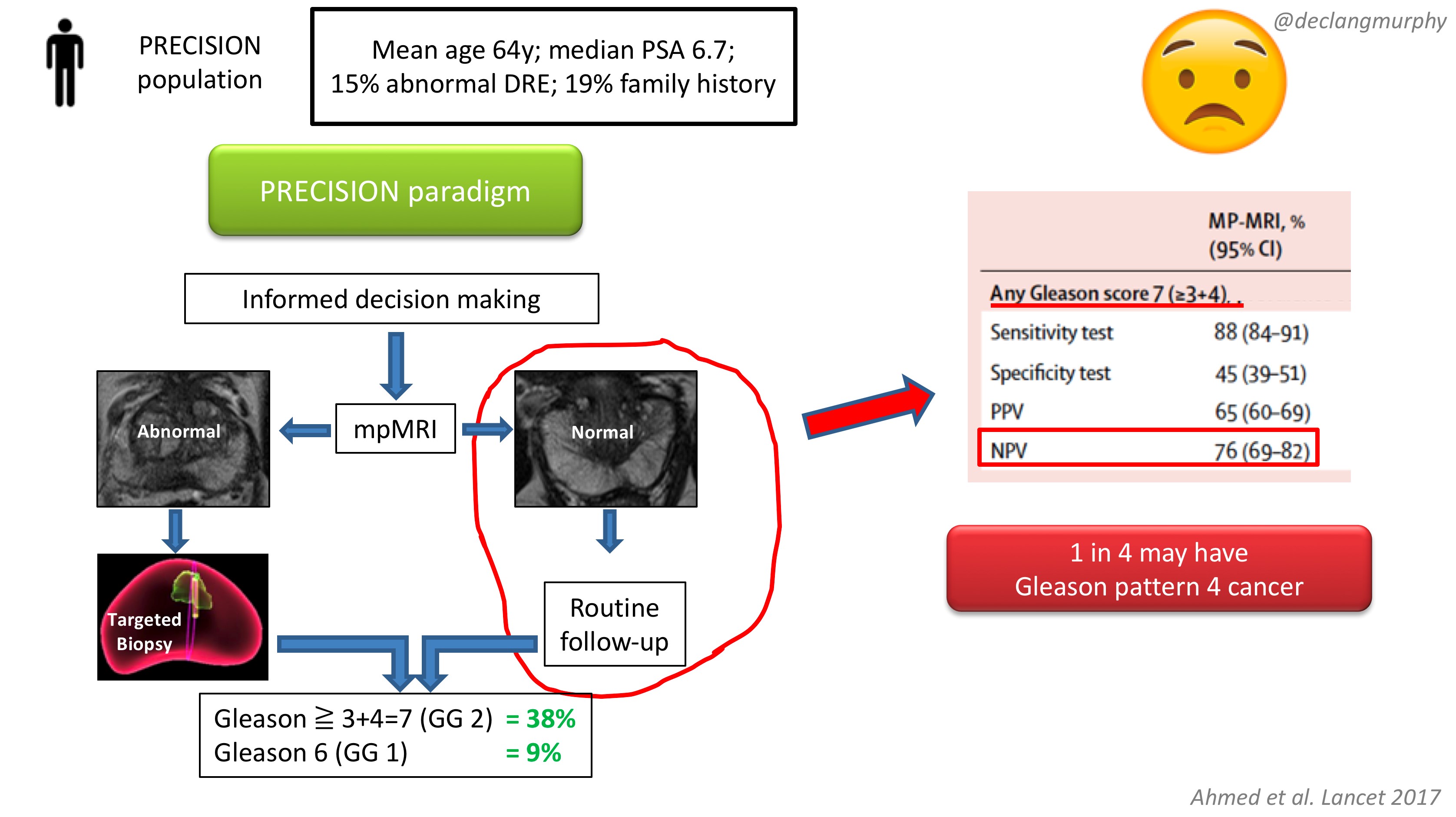

The obvious concern of course, is the fate of those patients with a normal MRI (28% of patients), who despite a clinical suspicion of prostate cancer, did not have a biopsy. How many clinically significant cancers might we miss by not offering biopsy to those patients? Of course, we already have an idea of what we would find, as the PROMIS study also included extensive biopsy (transperienal mapping) for patients with a normal MRI.

In PROMIS, the negative predictive value of MRI for detecting any pattern 4 cancer is 76% ie up to 1 in 4 men will have some pattern 4 cancer on transperineal biopsy. However, no primary pattern 4 cancers were missed on MRI. This is something we have to digest. I think that we can accept missing some pattern 4 cancers in some men, provided the “routine follow up” is adequate. But we must also continue to use the other tools we have in our multivariable approach to early detection, and if there are red flags due to family history, palpable nodules, adverse PSA parameters (including PSA density), BRCA mutations, then there will clearly be a role for systematic biopsy in some of these men with normal MRI scans.

In my opinion, we now have enough evidence to fully embrace mpMRI in our approach to early detection of prostate cancer. Following on from the PROMIS study, published in the Lancet 2017, the PRECISION study provides us with the imprimatur to fully embed MRI in the assessment of men with a suspicion of prostate cancer. The era of blind random prostate biopsy is surely over, except perhaps in those patients in whom MRI is contra-indicated. The next challenge will be to create enough capacity and expertise to make this paradigm available to all.

Resourcing will inevitably be an issue, but the PROMIS and PRECISION papers provide a compelling health economic argument for funders. Less men undergoing biopsy; less biopsy cores; less complications; less insignificant cancer – this surely makes economic sense. In Australia, where MRI has already been enthusiastically embraced, a high-quality mpMRI on a 3T machine costs $USD300, and costs are usually borne by patients. In the USA, we hear that a 1.5T MRI (with an endorectal coil) can cost USD$2-3000!! Why is this?! Australia is an expensive country – an iPhone or a da Vinci robot costs 1.5 times the cost in the USA; why therefore should an MRI cost so much in the USA? A symptom of a much broader issue with the bloated US health economy, and likely a barrier to adoption of the paradigm proposed by PRECISION.

So there you have it. A truly practice-changing study. While there will be much discussion about the nuances, I for one will immediately embrace this paradigm:

- MRI for all (I already do this)

- Targeted biopsy alone for those with MRI lesions (a new departure for me)

- No biopsy for those with normal MRI scans (unless there are other red flags).

My concluding slide from the plenary discussion:

Congrats again Veeru, Caroline, Mark and colleagues for publishing this landmark study.

Declan G Murphy

Urologist & Director of Genitourinary Oncology, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, Melbourne, Australia

Twitter: @declangmurphy