This blog  was originally published as a comment article in BJU International, 112: 11–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11780.x

was originally published as a comment article in BJU International, 112: 11–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11780.x

With the explosion and expansion of information technology, instantaneous dissemination of medical knowledge across the globe is a reality and here to stay. Performing live surgery to an audience, whether to the medical community or to the general public, has raised much controversy and continues to be hotly debated even today. While a recent article by a very senior urologist concentrated on the drawbacks of live surgery, little was written about the benefits [1]. We begin our debate with this ‘Benedictory Ode’ to live surgery:

Came the news about cancer of the prostate

Surgery, radiation or I had to be castrate

I was won over by the argument of the daVinci Robot

Surgical smile assured me protection of the lover’s knot

I was asked to be a patient for live surgery

I thought to myself, is it a circus or butchery?

Should I be scared, Should I be excited?

But was convinced many will be benefitted

My choice was voluntary and informed

Consent on the dotted line was performed

The day came and the day went

Surgery was smooth without a dent

Some might argue that I was a damn fool

But I am proud to have been an educational tool

Anonymous Patient

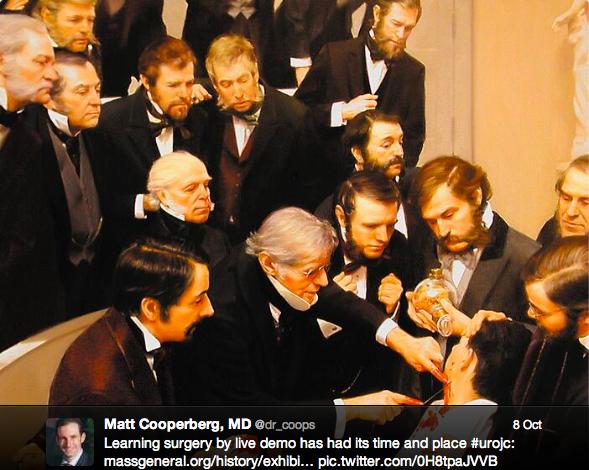

When did ‘live surgery’ really begin? Probably the answer would be as early as the birth of medicine itself. Medicine and surgery as we know them today have been based upon the ‘teacher–apprentice’ model for centuries. Whenever the ‘teacher’ became famous, apprentices from surrounding towns, and subsequently from surrounding countries, would flock to watch the way a diagnosis was made or indeed how the surgery was performed. In historical documents from the Middle Ages through to the Renaissance, we are reminded of the amphitheatre that was built especially to demonstrate anatomical dissections and surgeries. Indeed the very origin of the term ‘operating theatre’ probably stems from the fact that operations were carried out to an audience in a theatrical manner, as beautifully portrayed in many medical paintings across the world.

The birth of the first transmission of surgical procedures can be traced back to the famous British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) series ‘Your Life in Their Hands’. This was first aired in 1958 and eight episodes were then broadcast over the next two months. This innovative series was conceived with three goals: to investigate new medical techniques; to applaud the medical profession; and to provide ‘reassurance’ for citizens at home. At the end of that period, the BBC had received 909 letters from viewers praising the programme and only 37 letters from viewers who were against it [2].

Professor Arthur Smith rightly points out the death of a patient that occurred in 2006 during live surgery organised by The Japanese Society of Thoracic Surgeons [1]; however, we should highlight that the very next year, the Japanese Society for Cardiovascular Surgery, the Japanese Association for Thoracic Surgery and the Japanese Society for Vascular Surgery collaborated in the development of guidelines for performing live surgeries [3]. In their guidelines, they rightly emphasize the need for feedback on the outcome of a patient who has undergone live surgery:

‘When a fixed interval has elapsed after live surgery, the surgeon must report on the postoperative course followed by the patient at an organized Society or research meeting. By this means, the body organizing such a meeting can investigate each of the cases in which live surgery has been conducted, and assesses the appropriateness of the use of live surgery in each.’

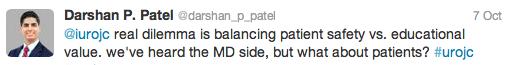

Recognizing the need for guidance for physicians and institutions with regard to live surgery, organisations such as the General Medical Council, AUA and the Royal College of Surgeons have published relevant guidelines. In their paper, Challacombe et al. [4] elegantly discuss the various aspects of the ethics of live surgery and highlight the important issues of patient consent and disclosures. We have followed the above guidelines for live robotic surgery to an audience and also to conduct the first live webcast in the UK of a robotic prostatectomy. Contrary to the norm, extra care is taken during live surgeries. Indeed, this may be an advantage for the patient as shown in Table 1. The operating surgeon is always an expert and, in our case, the surgeon was well trained to listen, respond to questions and operate without any hesitation. It is safe to assume that not all surgeons will achieve this high standard in their career. It is also vital to have a moderator who can manage the questions appropriately and convey them to the operating surgeon at the appropriate time.

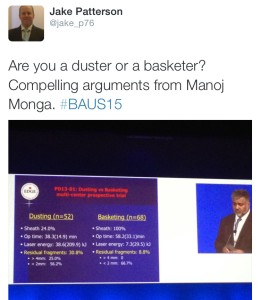

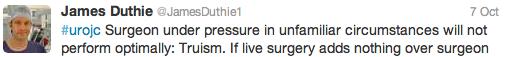

In the era of evidence-based medicine, no debate can be complete without presenting supporting data from the literature. Several studies across different specialties have looked at the outcomes of patients who have undergone live surgeries. None of the studies showed any adverse outcome in the cohort of patients who subjected themselves to live surgery. Recently, a study analysed the outcomes of patients undergoing robotic partial nephrectomy as a live broadcast as compared with a cohort treated without observers [5]. The authors concluded that live robotic surgery is associated with excellent patient outcomes that compare favourably with cases performed under normal operating procedures. There is further evidence that live surgery as part of a course has a powerful impact on the practice patterns of a urologist [6]. Surprisingly, there is no published evidence in the literature that these patients come to any harm. There are several surveys of surgeons across specialties in the literature with contradictory views on live surgery, but there is no denying that transmission of live surgeries is becoming more and more popular, as evidenced by the packed rooms at all major urological meetings.

Conclusion

Performing live surgery on a patient is here to stay and will be an integral part of the dissemination of medical knowledge. The obligation that the medical society has towards the field of live surgery is to ensure that the operation is performed by the ‘right surgeon on the right patient in a right environment and with the right intentions’.

Amrith R. Rao and Omer Karim

Department of Urology, Wexham Park Hospital, Wexham, Berkshire, UK

References

1 Smith A. Urological live surgery – an anathema. BJU Int 2012; 110: 299–300 Full Article (HTML)

2 van Lingen A. Your life in their hands. Published online 27 November 2006. Accessed at https://www.birth-of-tv.org/birth/assetView.do?asset=1413260435_1164637516. Accessed 28 August 2012

3 Misaki T, Takamoto S, Matsuda H, Shigematsu H. Joint Committee for the Establishment of Guidelines for the Live Session of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. Published August 2007. Available at https://jscvs.umin.ac.jp/eng/live.html. Accessed 28 August 2012

4 Challacombe B, Weston R, Coughlin G, Murphy D, Dasgupta P. Live surgical demonstrations in urology: valuable educational tool or putting patients at risk? BJU Int 2010; 106: 1571–1574 Full Article (HTML)

5 Mullins JK, Borofsky MS, Allaf ME et al. Live Robotic Surgery: are outcomes compromised? Urology 2012; 80: 602–607 Web of Science®

6 Altunrende F, Autorino R, Haber GP et al. Immediate impact of a robotic kidney surgery course on attendees practice patterns. Int J Med Robot. 2011; 7: 165–169. doi: 10.1002/rcs.384 Full Article (HTML)

Comments on this blog are now closed.