Port–Site recurrence following Laparoscopic Radical Nephrectomy for Chromophobe Renal Cell Carcinoma

Port-site metastasis following laparoscopic radical nephrectomy is being increasingly recognized as a complication following laparoscopic surgery, especially when correct surgical principles are violated. All previously reported cases have been of either the clear cell or papillary variant of renal cell carcinoma. Herein we report a case of chromophobe renal cell carcinoma with port-site recurrence 10 months after laparoscopic radical nephrectomy.

Authors: Javali, Tarun; Dogra, Premnath; Singh, Prabhjot

Corresponding Author: Javali, Tarun

Introduction

Port-site metastasis following laparoscopic radical nephrectomy is being increasingly recognized as a complication following laparoscopic surgery, especially when correct surgical principles are violated. All previously reported cases have been of either the clear cell or papillary variant of renal cell carcinoma. Herein we report a case of chromophobe renal cell carcinoma with port-site recurrence 10 months after laparoscopic radical nephrectomy.

Case History

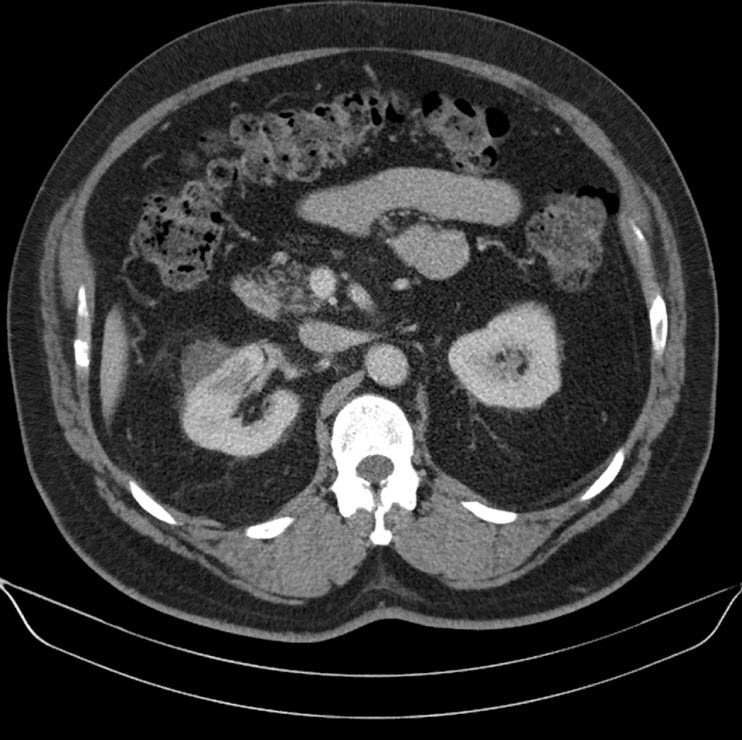

A 44 year old lady presented with a 6 month history of left flank pain and hematuria. Computed tomography revealed a 12×5×5 cms heterogeneous enhancing left renal upper pole mass. [Fig.1]. There was no evidence of lymph node enlargement or liver metastasis, and no tumor thrombus. The CT scan also revealed a multiloculated right adnexal cyst of size 6×4×4 cms. The patient underwent laparoscopic transperitoneal left radical nephrectomy and right oophorectomy. Additional ports were placed for the oophorectomy. The radical nephrectomy was performed first because it was deemed to be more technically challenging than the oophorectomy. Both the specimens were entrapped separately in retrieval bags and removed through a Pfannensteil incision. The specimen was not morcellated.

Histopathology revealed a chromophobe renal cell carcinoma. On immunohistochemical analysis, the tumor was positive for cytokeratin and negative for CD10 and vimentin. There was no evidence of any capsular breach. The tumor had reached the renal sinus but had not infiltrated it. Histopathology of the right oophorectomy specimen showed an endometrial cyst.

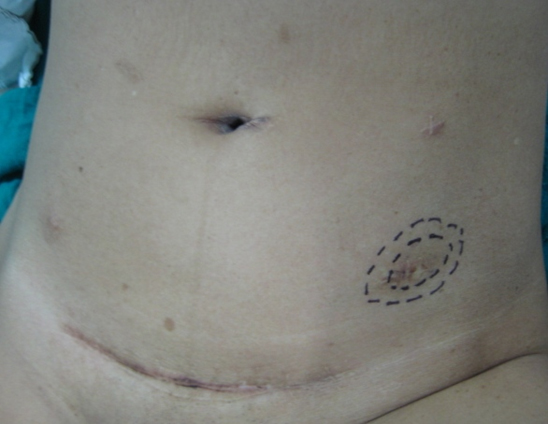

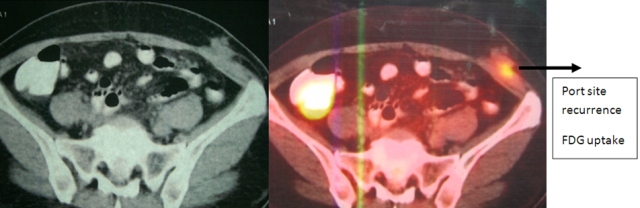

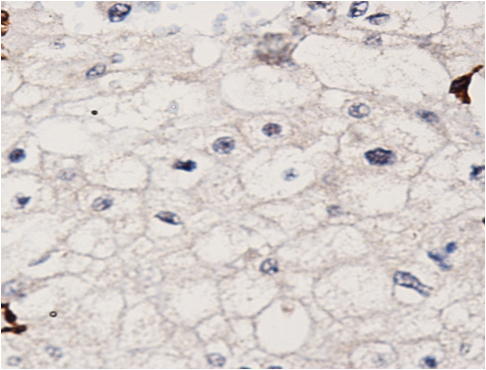

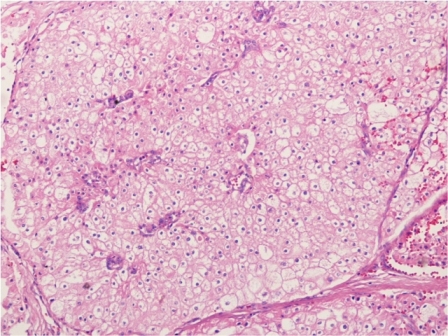

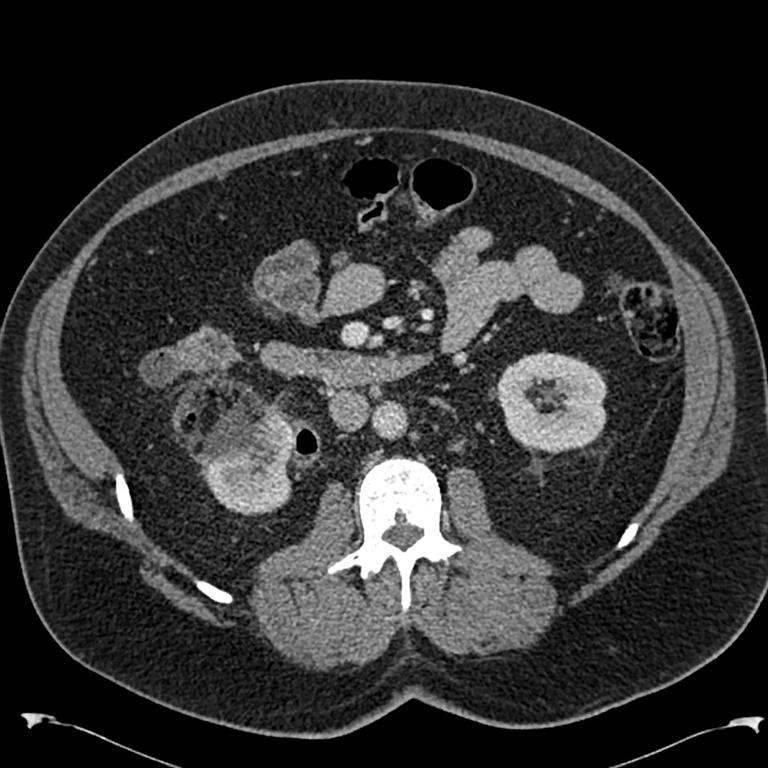

The patient was reviewed on a three monthly basis with a chest x-ray, liver and kidney function tests and a full blood count. No abdominal imaging was done at this time. Ten months after surgery, the patient presented with pain and swelling at one of the port sites. Examination revealed a hard subcutaneous nodule of size 2×1.5 cm at the 12mm working port site above and medial to the left anterior superior iliac spine [Fig 2]. The surgical incision site for specimen removal had no evidence of recurrence. The patient had already had fine needle aspiration cytology (F.N.A.C.) performed, which was reported as showing ‘malignant cells suspicious for renal cell carcinoma’. A contrast enhanced CT scan of her abdomen revealed an irregular enhancing subcutaneous soft tissue lesion in left anterior abdominal wall measuring 1.8 cms, thought likely to be a metastasis. The liver and right kidney were normal and there were no retroperitoneal nodes or masses. Positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) revealed increased 18-fluro deoxy glucose (18FDG) uptake in the soft tissue density lesion in left lower abdominal wall [Fig 3]. The patient underwent wide local excision of the port-site nodule. Histology revealed chromophobe renal cell carcinoma with the same histomorphology as the primary tumour [Fig 4,5].

At one year post excision of the port-site nodule, patient is well, and has had no recurrences, either local or systemic.

Discussion

Factors which have been implicated in port-site recurrence include natural tumor factors, local wound factors, immune response and laparoscopic related factors such as direct wound contamination, either instrument contamination or during specimen extraction, specimen morcellation, use of specimen retrieval bags and pneumoperitoneum pressure [1,2]. Poorly differentiated transitional cell carcinomas have accounted for most of the cases of port site recurrence in laparoscopic uro-oncologic case series [1,2,3]. Only a few cases of port site recurrence following laparoscopic nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma have been reported [4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. In all of these cases the histopathology was clear cell carcinoma. Russo et al reported a case of papillary renal cell carcinoma with port site metastasis following laparoscopic partial nephrectomy [11]. To the best of our knowledge this the first case of chromophobe renal cell carcinoma with port site recurrence. In the present case the tumor was organ confined (pT2) and well differentiated. Most studies report more favorable prognosis for chromophobe compared to conventional renal cell carcinoma. This goes against the commonly held notion that adverse tumor biology or aggressive nature of the tumor is the most important causative factor in port site recurrence [1]. Greco et al have further elaborated on the factors that accelerate the development of port-site metastasis [12]. These conditions include performing laparoscopic surgery in the presence of ascites, lack of trocar fixation to prevent dislodgement and gas leakage around the trocars, inadequate laparoscopic equipment and technique and tumour boundary violation. Factors which have deemed to reduce the incidence of port-site metastases include use of a bag for specimen retrieval, placement of drainage before desufflation, povidone-iodine irrigation of instruments, trocars and port-site wounds and suturing trocar wounds ≥10mm in size.

In the present case, all possible precautions were taken during the course of surgery, including changing the instruments, once the radical nephrectomy was over. A probable etiologic factor in this case may have been the prolonged operating time as laparoscopic nephrectomy was followed by laparoscopic oophorectomy and the gynaecologists also used the left sided 12mm working port. Microleakage around ports (“chimney effect”) has been postulated to play a role in port site metastasis [13]. Ports used by the main operating surgeon have been proved to have more contamination by tumor cells than either those used by the assistants or the camera port [14]. It is a matter of conjecture that whether performing the oophorectomy first followed by radical nephrectomy could have altered the result.

We wish to highlight two main points through this case report. Firstly, that tumor histology may not be predictive of port site recurrence. Chromophobe renal cell carcinoma is biologically a tumor of low malignant potential. Metastasis of chromophobe tumour constitute less than 1% of all metastatic renal cell carcinoma [15]. Advanced pathological T stage, tumor necrosis and sarcomatoid change have been purported to predict an aggressive phenotype of chromophobe renal cell carcinoma [16]. However none of these features were present in this case. Hence following laparoscopic radical nephrectomy patients need to be carefully examined at each visit with particular attention to the port sites. This should be done regardless of the grade, stage or histology of the tumor.

The second point we wish to highlight is that PET-CT could be a useful adjunct in diagnosing port-site recurrence in equivocal cases. This may be especially relevant in patients who return within a short span of time following laparoscopic radical nephrectomy, wherein induration due to surgical factors at scar site may be confused vis-a vis port site recurrence.

Fig. 1 – CT KUB (Kidney-ureter-bladder) showing left upper pole tumor.

Fig. 2 – Port-site nodule

Fig. 3 – PET-CT showing port-site metastasis

Fig. 4 – Hematoxylin and Eosin staining of excised port-site specimen. Sheets of cells with round to oval nuclei and perinuclear halo with prominent cell membranes.

Fig. 5 – Immunohistochemistry. Negative for CD10 and vimentin.

References

1. Rassweiler J, Tsivian A, Kumar AV, Lymberakis C, Schulze M, Seeman O, et al. Oncological safety of laparoscopic surgery for urological malignancy: experience with more than 1,000 operations. J Urol 2003; 169:2072–5.

2. Tsivian A, Sidi AA. Port site metastases in urological laparoscopic surgery. J Urol 2003; 169:1213–8.

3. Micali S, Celia A, Bove P, et al: Tumor seeding in urological laparoscopy: an international survey. J Urol 2004; 171: 2151–4.

4. Fentie DD, Barret PH, and Taranger LA: Metastatic renal cell carcinoma after laparoscopic radical nephrectomy: long term follow-up. J Endourol 2000; 14: 407–11.

5. Landman J, and Clayman R: Re: port site tumor recurrences of renal cell carcinoma after videolaparoscopic radical nephrectomy (letter). J Urol 2001; 166: 629–30..

6. Castilho LN, Fugita OEH, Mitre AI, et al: Port site tumor recurrences of renal cell carcinoma after videolaparoscopic radical nephrectomy. J Urol 2001; 165: 519.

7. Chen YT, Yang SSD, Hsieh CH, et al: Hand port-site metastasis of renal-cell carcinoma following hand-assisted laparoscopic radical nephrectomy: case report. J Endourol 2003; 17: 771–4.

8. Iwamura M, Tsumura H, Matsuda D, et al: Port site recurrence of renal cell carcinoma following retroperitoneoscopic radical nephrectomy with manual extraction without using entrapment sac or wound protector. J Urol 2004; 171: 1234–5.

9. Dhobada S, Patankar S, Fais F, et al: Port-site metastasis after laparoscopic radical nephrectomy for renal-cell carcinoma: case report. J Endourol 2006; 20: 119–22.

10. Goyal R., Sing P., Mandhani A. et al. Port-site metastatis of renal cell carcinoma after laparoscopic transperitoneal radical nephrectomy. Ind J of Urol 2006; 22:150-1.

11. Masterson TA, Russo P. A case of port-site recurrence and loco-regional metastasis after laparoscopic partial nephrectomy. Nature Reviews Urology 2008; 5:345-9.

12. Greco F, Wagner S, Reichelt O, Inferrera A, Lupo A, Hoda MR, Hamza A, Fornara P

Huge port-site metastasis after laparoscopic partial nephrectomy: a case report. Eur Urol 2009; 56:737-39.

13. Curet MJ: Port site metastases. Am J Surg 2004; 187: 705-12.

14. Ramirez PT, Wolf JK, and Levenback C: Laparoscopic port-site metastases: etiology and prevention. Gynecol Oncol 2003; 91: 179–89.

15. Choueiri TK, Plantade A, Elson P et al. Efficacy of sunitinib and sorafenib in metastatic papillary and chromophobe renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26:127-31.

16. Amin MB, Paner GP, Alvarado-Cabrero I et al. Chromophobe renal cell carcinoma: histomorphologic characteristics and evaluation of conventional pathologic prognostic parameters in 145 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2008; 32:1822-34.

Date added to bjui.org: 05/12/2012

DOI: 10.1002/BJUIw-2012-035-web