Primary synovial sarcoma (PSS) of the kidney is a rare occurrence, with preoperative diagnosis difficult to distinguish from other renal neoplasms. Presented here is the case of a patient who underwent elective left laparoscopic nephrectomy for a 6-cm renal mass. Intra-operatively, she decompensated into PEA from multiple pulmonary emboli secondary to dislodged tumor thrombus requiring emergent sternotomy and embolectomy after placing the patient on cardiopulmonary bypass. Patient survived the surgery and has been placed on adriamycin, ifosfomide, mesna (AIM) chemotherapy. However, no definitive treatment of renal synovial sarcoma exists and prognosis is bleak despite primary surgical resection, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy.

Authors: Zhao, Philip; Mikkilineni, Nina; Johnson, Kelly; Ankem, Murali

Corresponding Author: Philip Zhao MD, Division of Urology, Department of Surgery, UMDNJ-Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, NJ 08901, USA. Email: zhaoph@umdnj.edu

Abstract

Primary synovial sarcoma (PSS) of the kidney is a rare occurrence, with preoperative diagnosis difficult to distinguish from other renal neoplasms. Presented here is the case of a patient who underwent elective left laparoscopic nephrectomy for a 6-cm renal mass. Intra-operatively, she decompensated into PEA from multiple pulmonary emboli secondary to dislodged tumor thrombus requiring emergent sternotomy and embolectomy after placing the patient on cardiopulmonary bypass. Patient survived the surgery and has been placed on adriamycin, ifosfomide, mesna (AIM) chemotherapy. However, no definitive treatment of renal synovial sarcoma exists and prognosis is bleak despite primary surgical resection, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy.

Introduction

Synovial sarcoma of the kidney was reported first by Faria et al. and Argani et al. in the beginning of the twenty-first century as a distinct subset of the embryonal sarcoma of the kidney [1,2]. Although synovial tumors occur primarily in the para-articular joints of extremities, they have been encountered in the lungs, mediastinum, heart, pharynx/larynx, kidneys, and other organs. Primary renal synovial sarcoma is extremely rare, with less than thirty-five cases reported in the literature [3, 4]. Its diagnosis cannot be based on imaging studies alone – it looks similar to other renal neoplasms on CT or MRI scans, but must be confirmed by molecular and cytogenetic analysis demonstrating the chromosomal translocation of t(X;18)(p11;q11) [2]. The disease is clinically aggressive and because of the paucity of cases, there are no optimal treatment plans except complete resection and a combination of adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy [5]. We present a case of PSS of the kidney that, during nephrectomy, embolized the pulmonary arterial system, causing catastrophic decompensation, requiring the patient to undergo cardiopulmonary bypass with emergency embolectomy.

Case Report

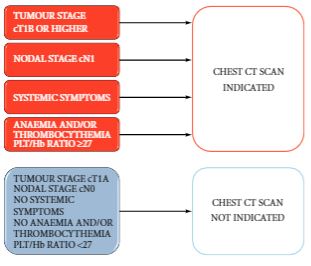

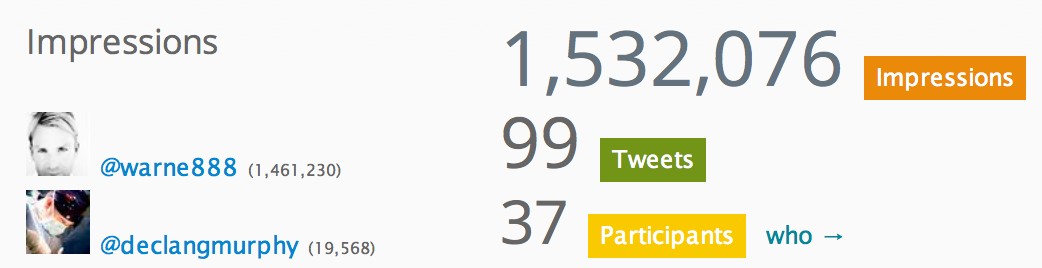

A 44-year-old female initially presented in March 2011 with gross haematuria and left flank pain, and workup revealed a heterogeneous 6 x 5 cm left upper pole renal mass. A metastatic evaluation was negative. The patient had no prior medical or surgical history and was a non-smoker. Anxious with her diagnosis, she elected to have an elective laparoscopic nephrectomy performed at the earliest available time. An abdominopelvic CT scan with IV contrast (Figure 1) done two weeks prior to date of surgery showed the tumor without any extensive invasion outside of the kidney and with only an element of left renal vein involvement, that id extend into the vena cava. In fact, the edge of the tumor thrombus was about 1.5 cm from the IVC.

The patient underwent a left laparoscopic radical nephrectomy in April 2011 in the standard manner. After placing the patient in the right lateral decubitus position and creating the pneumoperitoneum, surgery proceeded uneventfully until dissection of the renal hilum. The left renal artery was identified and stapled without difficulty. The left gonadal, adrenal, and lumbar veins were all identified and ligated. The left renal vein was then dissected and a vascular stapler was slowly closed flush to the IVC and then pushed laterally towards the kidney before closing completely and firing. Immediately after firing the vascular stapler, the patient became bradycardic, hypotensive, and hypoxic, eventually leading to PEA. A catastrophic event was suspected and the surgery immediately ceased with deflation of the pneumoperitoneum, removal of all laparoscopic ports, and placement of the patient in the supine position. Although a tension pneumothorax was initially suspected, TEE confirmed significant right ventricular (RV) distension and signs of pulmonary embolism. Aggressive cardiopulmonary resuscitation began and cardiothoracic surgery was emergently consulted for cardiopulmonary bypass and embolectomy.

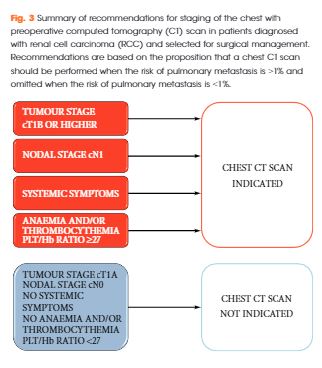

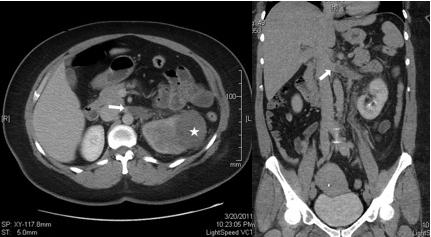

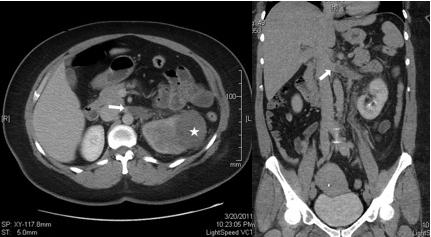

A femoral-femoral bypass was established and a standard sternotomy was performed with the pericardium opened. The RV was significantly dilated and there was high pulmonary arterial pressure by palpation. The right atrium (RA) and ascending aorta were both cannulated and the femoral lines were switched to the aortic arterial line and venous outflow from the RA to reestablish bypass. The patient was then systemically cooled to approximately 31 degrees Celsius. The pulmonary artery was then opened in a longitudinal direction and multiple clots as well as tumor thrombi were then removed from all the pulmonary arterial segmental branches on both the left and right sides (Figure 2). A frozen section sent off revealed spindle cell tumor. After all clots and tumors had been removed, the pulmonary artery was closed along with the chest, while keeping a chest tube in place. The nephrectomy was completed by making a left subcostal incision and removing the entire left kidney. A JP drain was left in place and the abdomen was then closed.

The patient remained intubated in the ICU and was weaned off the ventilator on post-operative day three. The rest of her hospitalization was complicated by acute renal failure, from which she was able to recover. Upper extremity DVT also developed, for which she was placed on therapeutic enoxaparin. The patient was ultimately discharged from the hospital to begin outpatient chemotherapy with adriamycin, ifosfomide, mesna (AIM). Pathological confirmation of primary monophasic synovial sarcoma of the kidney was obtained, with molecular studies detecting SYT-SSX2 fusion transcripts consistent with t(X,18) translocation. Although the fascial margins of the tumor were negative, there was extensive lymphovascular invasion and extension into the renal sinus. Final pathology of the pulmonary thrombi demonstrated metastatic synovial sarcoma.

A PET scan done a month after patient’s operation revealed extensive areas of hypermetabolic nodules and soft tissue densities in the left renal bed and significant lymphadenopathy in the retroperitoneum coursing down the left ureter consistent with metastatic spread of the cancer. A repeat CT scan of the chest also revealed a non-occlusive filing defect at the bifurcation of the right main pulmonary artery suggesting in situ thrombus, as well as new lytic osseous lesions in the intervertebral bodies suspicious for osseous metastases.

Discussion

Primary synovial sarcoma of the kidney is rare and tumors presenting with IVC thrombus are fewer still-there are only four cases reported in the literature [4]. Our case is the first report of a PSS thrombus dislodging and embolizing the pulmonary arterial tree, causing immediate decompensation and requiring emergency sternotomy and embolectomy after placing the patient on cardiopulmonary bypass. The case is especially interesting and highlights the aggressiveness of this tumor variant because only two weeks prior to surgery, a CT scan showed a grossly patent IVC with minimal tumor invasion of the left renal vein. There was a wide discrepancy between the amount of tumor burden removed from the pulmonary arteries and the small tumor thrombus in the renal vein identified on CT scan. A case may have been made for additional imaging (MRI) to better define the level of tumor thrombus. However, recent literature shows that CT and MRI both detect and assess caval thrombus with similar sensitivity and specificity –78% and 72%, 88% and 76%, respectively [6]. In retrospect, we could have used an intra-operative ultrasound to better delineate the exact edge of the tumor thrombus in the renal vein prior to ligation. We did not because of the grossly patent IVC on recent imaging and because the attending surgeon felt confident in his technique of closing the stapler partway and then “milking” any thrombus away from the IVC before firing.

There is no preoperative method to diagnose PSS without tissue samples for analysis. Differential diagnosis includes adult Wilms tumor, renal cell carcinomas, mesoblastic nephromas, primitive neuroectodermal tumors, primary renal rhabdosarcomas, and transitional cell carcinomas. Using reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), Argani et al. were able to identify the presence of SYT-SSX gene fusion from t(X; 18) [2]. Although five different variants of the SSX gene have been identified, only SSX1 and SSX2 have been shown to fuse with the SYT gene to create the biphasic and monophasic forms of PSS, respectively. Biphasic PSS contains both glandular and spindle epithelial elements while the monophasic form is only composed of spindle cells [4, 7]. The only consistent immunoreactive marker for PSS is vimentin, which was markedly positive in our patient’s tumor.

Although surgery is the mainstay of therapy, it is not enough alone to augment the already poor prognosis associated with renal PSS. Although there have been limited success with stereotactic body radiotherapy and ifosamide and doxorubicin-based chemotherapy with case reports showing complete remission after post-nephrectomy metastasis to the lung, most patients do not live beyond two years [8, 9, 10].

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

References

1. Faria P, Argani P, Epstein J. Primary synovial sarcoma of the kidney: A molecular subset of so called embryonal renal sarcoma. Mod Pathol Am. 1999;12:94.

2. Argani P, Faria PA, Epstein JI, Reuter VE, Perlman EJ, Beckwith JB, Ladanyi M. Primary renal synovial sarcoma: molecular and morphologic delineation of an entity previously included among embryonal sarcomas of the kidney. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000 Aug;24(8):1087-96.

3. Gabilondo F, Rodríguez F, Mohar A, Nuovo GJ, Domínguez-Malagón H. Primary synovial sarcoma of the kidney: corroboration with in situ polymerase chain reaction. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2008;12:134-7.

4. Dassi V, Das K, Singh BP, Swain SK. Primary synovial sarcoma of kidney: A rare tumor with an atypical presentation. Indian J Urol. 2009 Apr-Jun;25(2): 269-271.

5. Kataria T, Janardhan N, Abhishek A, Sharan GK, Mitra S. Pulmonary metastasis from renal synovial sarcoma treated by stereotactic body radiotherapy: a case report and review of the literature. J Cancer Res Ther. 2010 Jan-Mar;6(1):75-9.

6. Hallscheidt PJ, Fink C, Haferkamp A, Bock M, Luburic A, Zuna I, Noeldge G, Kauffmann G. Preoperative staging of renal cell carcinoma with inferior vena cava thrombus using multidetector CT and MRI: prospective study with histopathological correlation. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2005 Jan-Feb;29(1):64-8.

7. Skytting B, Nilsson G, Brodin B, Xie Y, Lundeberg J, Uhlen M, et al. A novel fusion gene, SYT-SSX4: In synovial sarcoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:974-5.

8. Kataria T, Janardhan N, Abhishek A, Sharan GK, Mitra S. Pulmonary metastasis from renal synovial sarcoma treated by stereotactic body radiotherapy: a case report and review of the literature. J Cancer Res Ther. 2010 Jan-Mar;6(1):75-9.

9. Park SJ, Kim HK, Kim CK, Park SK, Go ES, Kim ME, et al. A case of renal synovial sarcoma: Complete remission was induced by chemotherapy with Doxorubicin and Ifosamide. Korean J Intern Med. 2004;19:62-5.

10. Long JA, Dinia EM, Saada-Sebag G, Cyprien J, Pasquier D, Thuillier C, Terrier N, Boillot B, Descotes JL, Rambeaud JJ. Primitive renal synovial sarcoma: a cystic tumor in young patients. Prog Urol. 2009 Jul;19(7):474-8.

Date added to bjui.org: 26/11/2012

DOI: 10.1002/BJUIw-2012-070-web