Every Week the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Week from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to the article itself, there is an accompanying editorial written by a prominent member of the urological community. This blog is intended to provoke comment and discussion and we invite you to use the comment tools at the bottom of each post to join the conversation.

Finally, the third post under the Article of the Week heading on the homepage will consist of additional material or media. This week we feature a video from Giuseppe Morgia and Giorgio Ivan Russo, discussing their paper.

If you only have time to read one article this week, it should be this one.

Patterns of prescription and adherence to European Association of Urology guidelines on androgen deprivation therapy in prostate cancer: an Italian multicentre cross-sectional analysis from the Choosing Treatment for Prostate Cancer (CHOICE) study

Giuseppe Morgia1, Giorgio Ivan Russo1, Andrea Tubaro2, Roberto Bortolus3, Donato Randone4, Pietro Gabriele5, Fabio Trippa6, Filiberto Zattoni7, Massimo Porena8, Vincenzo Mirone9, Sergio Serni10, Alberto Del Nero11, Giancarlo Lay12 , Umberto Ricardi13, Francesco Rocco14, Carlo Terrone15, Arcangelo Pagliarulo16, Giuseppe Ludovico17, Giuseppe Vespasiani18, Maurizio Brausi19, Claudio Simeone20, Giovanni Novella21, Giorgio Carmignani22, Rosario Leonardi23, Paola Pinnaro5, Ugo De Paula24, Renzo Corvo25, Raffaele Tenaglia26, Salvatore Siracusano27, Giovanna Mantini28, Paolo Gontero29, Gianfranco Savoca30 and Vincenzo Ficarra31 (Members of the LUNA Foundation, Societa Italiana d’Urologia)

1 Department of Urology, University of Catania, Catania, 2 Department of Urology, Sant’ Andrea Hospital, ‘La Sapienza’ University of Roma, Roma, 3 S.O. Oncologia Radioterapica, Pordenone, 4 Urology, Presidio Ospedaliero Gradenigo, Torino, 5 Radiotherapy, IRCC Candiolo, Torino, 6 Radiotherapy, A.O. Santa Maria, Terni, 7 Department of Urology, University of Padova, Padova, 8 Department of Urology, University of Perugia, Perugia, 9 Department of Urology, Universita Federico II of Napoli, Napoli,

10 Department of Urology, University of Firenze, Firenze, 11 Urologia I, Azienda Ospedaliera San Paolo, Milano, 12 Radiotherapy, ASL of Cagliari, Cagliari, 13 Radiotherapy, AOU University S. Giovanni Battista Molinette, Torino, 14 Department of Urology, University of Milano, Milano, 15Urology, University Hospital ‘Maggioredella Carita’, Novara,16 Urology, University of Bari, Bari, 17 Urology, Ospedale Generale Regionale F. Miulli, Acquaviva delle Fonti, 18 Department of Urology, University Tor Vergata, Roma, 19 Urology, Ospedale Civile Ramazzini, Carpi, 20 Department of Urology, University of Brescia, Brescia, 21 Department of Surgery, Urology Clinic, AOUI Verona, Verona, 22 Department of Urology, University of Genova, Genova, 23 Urology, Centro Uro-Andrologico La CURA, Acireale, 24 Radiotherapy, AO S. Giovanni Addolorata, Roma, 25 Radiotherapy, Istituto Nazionale per la Ricerca, Genova, 26 Department of Urology, University of Chieti, Chieti, 27 Department of Urology, University of Trieste, Trieste, 28 Radiotherapy, Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemelli, Roma, 29 Department of Surgical Sciences, Città della Salutee della Scienza, University of Torino, Torino, 30 Urology, Fondazione Istituto San Raffaele – G. Giglio di Cefalù, Cefalù, and 31 Department of Experimental and Clinical Medical Sciences, University of Udine, Udine, Italy

Objective

To evaluate both the patterns of prescription of androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) in patients with prostate cancer (PCa) and the adherence to European Association of Urology (EAU) guidelines for ADT prescription.

Methods

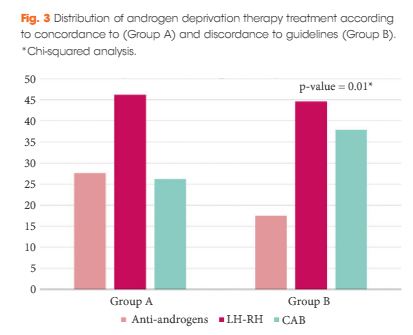

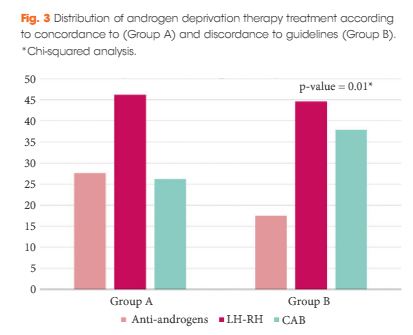

The Choosing Treatment for Prostate Cancer (CHOICE) study was an Italian multicentre cross-sectional study conducted between December 2010 and January 2012. A total of 1 386 patients, treated with ADT for PCa (first prescription or renewal of ADT), were selected. With regard to the EAU guidelines on ADT, the cohort was categorized into discordant ADT (Group A) and concordant ADT (Group B).

Results

The final cohort included 1 075 patients with a geographical distribution including North Italy (n = 627, 58.3%), Central Italy (n = 233, 21.7%) and South Italy (n = 215, 20.0%). In the category of patients treated with primary ADT, a total of 125 patients (56.3%) were classified as low risk according to D’Amico classification. With regard to the EAU guidelines, 285 (26.51%) and 790 patients (73.49%) were classified as discordant (Group A) and concordant (Group B), respectively. In Group A, patients were more likely to receive primary ADT (57.5%, 164/285 patients) than radical prostatectomy (RP; 30.9%, 88/285 patients), radiation therapy (RT; 6.7%, 19/285 patients) or RP + RT (17.7%, 14/285 patients; P < 0.01). Multivariate logistic regression analysis, adjusted for clinical and pathological variables, showed that patients from Central Italy (odds ratio [OR] 2.86; P < 0.05) and South Italy (OR 2.65; P < 0.05) were more likely to receive discordant ADT.

Conclusion

EAU guideline adherence for ADT was low in Italy and was influenced by geographic area. Healthcare providers and urologists should consider these results in order to quantify the inadequate use of ADT and to set policy strategies to overcome this risk.