Posts

Article of the week: Update on the guideline of guidelines: non‐muscle‐invasive bladder cancer

Every week, the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Week from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to this post, there is also a video produced by the authors. Please use the comment buttons below to join the conversation.

If you only have time to read one article this week, we recommend this one.

Update on the guideline of guidelines: non‐muscle‐invasive bladder cancer

Jacob Taylor , Ezequiel Becher and Gary D. Steinberg

Department of Urology, NYU Langone Health, New York, NY, USA

Abstract

Non‐muscle‐invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) is the most common form of bladder cancer, with frequent recurrences and risk of progression. Risk‐stratified treatment and surveillance protocols are often used to guide management. In 2017, BJUI reviewed guidelines on NMIBC from four major organizations: the American Urological Association/Society of Urological Oncology, the European Association of Urology, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. The present update will review major changes in the guidelines and broadly summarize new recommendations for treatment of NMIBC in an era of bacillus Calmette‐Guérin shortage and immense novel therapy development.

Video: Update on the guideline of guidelines: non‐muscle‐invasive bladder cancer

Update on the guideline of guidelines: non‐muscle‐invasive bladder cancer

Abstract

Non‐muscle‐invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) is the most common form of bladder cancer, with frequent recurrences and risk of progression. Risk‐stratified treatment and surveillance protocols are often used to guide management. In 2017, BJUI reviewed guidelines on NMIBC from four major organizations: the American Urological Association/Society of Urological Oncology, the European Association of Urology, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. The present update will review major changes in the guidelines and broadly summarize new recommendations for treatment of NMIBC in an era of bacillus Calmette‐Guérin shortage and immense novel therapy development.

Editorial: How long is long enough for pharmacological thromboprophylaxis in urology?

Each year, millions of patients who undergo urological surgery incur the risk of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, together referred to as venous thromboembolism (VTE), and major bleeding. Because pharmacological prophylaxis decreases the risk of VTE, but increases the risk of bleeding, and because knowledge of the magnitude of these risks remains uncertain, both clinical practice and guideline recommendations vary widely [1]. One of the uncertainties is the recommended duration of pharmacological thromboprophylaxis.

In this issue of the BJUI, Naik et al. [2] provide an up‐to‐date review that summarises the articles that examined extended thromboprophylaxis in patients with cancer who underwent radical prostatectomy (RP), radical cystectomy (RC) or nephrectomy. The outcomes on which they focussed include risks of VTE, bleeding, renal failure and mortality – all potentially influenced by whether or not patients receive extended prophylaxis.

After screening >3500 articles, the authors included 18 studies, none of them randomised controlled trials (RCTs) [2]. They found that VTE risk is highest in open and robot‐assisted RC, and that, based on observational studies, extended thromboprophylaxis significantly reduces the risk of VTE relative to shorter duration prophylaxis. Evidence suggested that robot‐assisted RP, as well as both open and robot‐assisted partial and radical nephrectomies, incur lower VTE risk than RCs or open RP. They did not find studies comparing extended prophylaxis to standard prophylaxis for RPs or nephrectomies [2].

Overall, these findings are consistent with systematic reviews that estimated the procedure‐ and patient risk factor‐specific risks for 20 urological cancer procedures [3]. As these reviews suggested substantial procedure‐specific differences in the VTE risk estimates, the European Association of Urology (EAU) Guidelines provided separate recommendations for each procedure [4]. For urological (as well as gastrointestinal and gynaecological) patients, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Guidelines suggest to ‘consider extending pharmacological VTE prophylaxis to 28 days postoperatively for people who have had major cancer surgery in the abdomen’ [5]. Because of variation in both bleeding and thrombosis risks across procedures, this advice is appropriate for some procedures and misguided for others. For instance, the procedure‐specific EAU Guidelines recommend extended VTE prophylaxis for open RC but not for robot‐assisted RP without lymphadenectomy [4].

The review by Naik et al. [2] identified the lack of urology‐specific studies comparing the in‐hospital‐only prophylaxis to extended prophylaxis. The few included studies were observational with considerable limitations (e.g. limited adjustment for possible confounders).

A recent update of a Cochrane review compared the impact of extended thromboprophylaxis with low‐molecular‐weight heparin (LMWH) for at least 14 days to in‐hospital‐only prophylaxis in abdominal or pelvic surgery procedures [6]. The authors identified seven RCTs (1728 participants) evaluating extended thromboprophylaxis with LMWH and generated pooled estimates for the incidence of any VTE (symptomatic or asymptomatic) after major abdominal or pelvic surgery of 13.2% in the control group compared with 5.3% in the patients receiving extended out‐of‐hospital LMWH (odds ratio [OR] 0.38, 95% CI 0.26–0.54).

Most events were asymptomatic, although the incidence of symptomatic VTE was also reduced from 1.0% in the in‐hospital‐only group to 0.1% in patients receiving extended thromboprophylaxis (OR 0.30, 95% CI 0.08–1.11). The authors reported no persuasive difference in the incidence of bleeding complications within 3 months of surgery (defined as major or minor bleeding according to the definition provided in the individual studies) between the in‐hospital‐only group (2.8%) and extended LMWH (3.4%) group (OR 1.10, 95% CI 0.67–1.81).

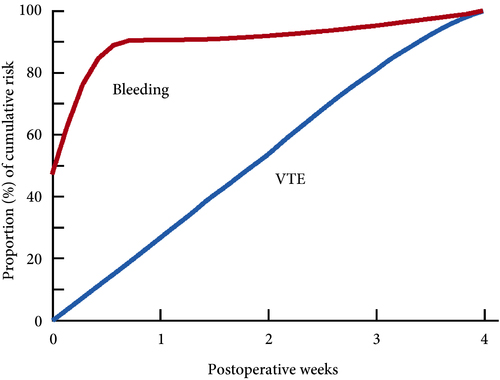

These findings are consistent with our own modelling study that demonstrated an approximately constant hazard of VTE up to 4 weeks after surgery [7]. That study also found that bleeding risk, by contrast, is concentrated in the first 4 days after surgery [7] (Fig.1). Using these findings, the EAU Guidelines suggest for patients in whom pharmacological prophylaxis is appropriate, extended pharmacological prophylaxis for 4 weeks [4]. Consistent with these recommendations, Naik et al. [2] found that 15 studies of 18 included in their review recommended extended prophylaxis.

Fig.1 Proportion of cumulative risk (%) of venous thromboembolism (VTE) and major bleeding by week since surgery during the first 4 postoperative weeks. Reproduced from: Tikkinen et al. [7].

(This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.)

Overall, as shown also by this review [2], the evidence base for urological thromboprophylaxis is limited. Although current evidence supports extended prophylaxis, definitively establishing the optimal duration of thromboprophylaxis will require large‐scale RCTs. Other unanswered key questions include: baseline risks of various procedures, timing of prophylaxis, patient risk stratification, as well as effectiveness of direct oral anticoagulants. In the meanwhile, suggesting extended duration to patients whose risk of VTE is sufficiently high constitutes a reasonable evidence‐based approach to VTE prophylaxis.

by Kari A.O. Tikkinen and Gordon H. Guyatt

References

- , , , , Guidelines of guidelines: thromboprophylaxis for urological surgery. BJU Int 2016; 118: 351– 8

- , , The role of extended venous thromboembolism prophylaxis for major urological cancer operations. BJU Int 2019; 124: 935-44

- , , et al. Procedure‐specific risks of thrombosis and bleeding in urological cancer surgery: systematic reviews and meta‐analyses. Eur Urol 2018; 73: 242– 51

- , , et al. EAU Guidelines on Thromboprophylaxis in Urological Surgery, 2017. European Association of Urology, 2018. Accessed November 2019

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Venous Thromboembolism in over 16s: reducing the risk of hospital‐acquired deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism. NICE guideline [NG89]. London: NICE, 2018. Accessed November 2019

- , , et al. Prolonged thromboprophylaxis with low molecular weight heparin for abdominal or pelvic surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019; 3: CD004318

- , , et al. Systematic reviews of observational studies of risk of thrombosis and bleeding in urological surgery (ROTBUS): introduction and methodology. Syst Rev 2014; 23: 150. DOI: 10.1186/2046‐4053‐3‐150.

NICE Stone Guidelines 2019

The NICE (National Institute For Health And Care Excellence) “Renal and ureteric stones: assessment and management” guideline NG118 was published on-line on Tuesday 8th January 2019 and appeared on the BJUI website on Friday 18th January.

NICE guidelines are based on the best available evidence for the treatment of the specific clinical condition evaluated (i.e. from randomised controlled trials) and aim to provide recommendations that will improve the quality of healthcare within the NHS. As such, the need for a particular guideline is determined by NHS England, and NICE commissions the NGC produce it. The renal and ureteric stone guidelines are comprised a series of evidence reports, each based on the PICO system for a systematic review, covering the breadth of stone management in patients with symptomatic and asymptomatic renal or ureteric stones from initial diagnosis and pain management, through the much debated subject of medical expulsive therapy, to a comprehensive assessment of the surgical treatment of stone disease, including pre- and post- treatment stenting. Follow up imaging, dietary intervention and metabolic investigations have also been reviewed and analysed in detail. These reports are summarised in what is referred to as “The NICE Guideline”, and which is published in the BJUI itself in the February issue (Volume 123, Issue 2, February 2019). The guideline uses the term “offer” to indicate a strong recommendation with the alternative “consider” to indicate a less robust evidence base, with both terms chosen to highlight the need for patient-centred discussion and shared decision making. Indeed, the preface to The Guideline points out the importance of clinical judgment, and that “the individual needs, preferences and values” of patients should be taken into account in decision making, emphasising that “the guideline does not override the responsibility to make decisions appropriate to the circumstances of the individual”.

We have written these blogs to highlight the individual reports, which can be downloaded from NICE at www.nice.org.uk, and to stimulate some thoughts and comments about their implications for the management of stone patients in the UK and internationally.

Daron Smith and Jonathan Glass

Institute of Urology, UCH and Guys and St Thomas’ Hospitals

London, January 15th 2019

Daron Smith Commentary

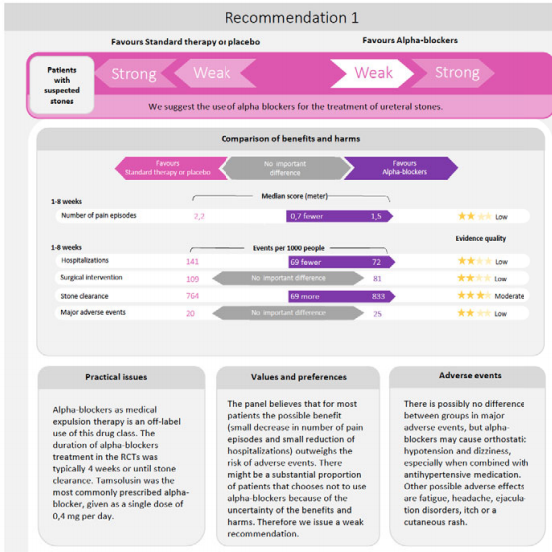

Considering the patient journey to begin with acute ureteric colic, the first recommendation is that a low-dose non-contrast CT should be performed within 24 hours of presentation (unless a child or pregnant) [Evidence Review B, a 73 page document analysing 5224 screened articles, of which 13 were of sufficient quality to be included in the review]. Their pain management should be with NSAIDs as first line pain relief, i.v. paracetamol as second line and opioids as third line, but antispasmodics should not be used [Evidence Review E, a 227 page document for which 1685 articles were screened, of which 38 were of sufficient quality to be included in the review]. Somewhat contentiously for UK practice, given the SUSPEND findings, is that alpha blockers should be considered for patients with distal ureteric stones less than 10 mm [Evidence Review D, a 424 page document for which 1351 articles were screened, of which 71 were of sufficient quality to be included in the review].

As far as stone interventions are concerned, observation was deemed to be reasonable for asymptomatic stones, especially if less than 5mm, that ESWL should be offered for renal stones less than 10mm and PCNL offered for those greater than 20mm with those in between having all options to be considered. Ureteric stones less than 10mm should be offered ESWL (unless unlikely to be cleared within 4 weeks, or contraindicated, or previously failed) whereas ureteric stones larger than 10mm should be offered URS. These conclusions were drawn from 2459 articles of which 66 were of sufficient quality to be included and summarised [Evidence Review F, a 369 page document]. Perhaps the most important aspect for change in practice relate to the use of stents (both before and after treatment) and the timing of definitive intervention (i.e. without a prior temporising JJ stent). Specifically, the guidance recommends patients with uncontrolled pain, or where the stone is deemed unlikely to pass spontaneously, should have definitive treatment within 48 hours [Evidence Review G, a 39 page document based on 3234 screened articles of which 3 were of sufficient quality to be included in the review]. Stents should not be inserted before ESWL for either renal or ureteric stones [Evidence Review H, a78 page document for which 1630 articles were screened, 7 being sufficiently high quality to be included in the review]. Patients who undergo URS for stones less than 20mm should not have a post-operative stent placed as a matter of routine [Evidence Review I, a 107 page document derived from 1630 screened articles of which 17 were of sufficient quality to be included in the review]. Clearly individual circumstances (ureteric trauma, need for second phase procedure, infection, risk of renal insufficiency) apply to this decision. Given that currently a URS is reimbursed at £2,172, and stent removal as £1,018, perhaps it is time that the treatment episode is remunerated as a combined £3,190, thereby encouraging stent-less procedures instead of stented ones…

Once the treatment is complete, the optimum frequency of follow-up imaging was assessed, comparing monitoring visits less than 6 monthly against 6 monthly and with rapid access/review on request, a strategy that includes no follow up at all for asymptomatic patients [presented in the 29 page Evidence Review J, in which 2385 articles were screened, but none of which were of sufficient quality to be included in the review]. No specific recommendations could therefore be made, other than the need to specifically evaluate the effectiveness of 6 monthly reviews for three years in future research. Of course, if preventative management were more effective, then imaging review would become less important… The guidelines have also reviewed the non-surgical options to avoid stone recurrence [summarised in Evidence Review K – “prevention of recurrence” – a 141 page document in which 3187 articles were screened, of which 19 were of sufficient quality to be included in the review and Evidence Review C, an 81 page document in which 1785 articles were screened, of which 10 were of sufficient quality to be included in the review]. These advised a fluid intake of 2.5 to 3 litres of water per day (with added lemon juice) and that dietary sodium intake should be restricted but calcium intake should not. As far as medical therapy is concerned, potassium citrate and thiazide diuretics should be considered in patients with calcium oxalate stones and hypercalciuria respectively.

In the final aspect of the pathway for stone patients, the clinical and cost effectiveness of metabolic investigations including stone analysis, blood and urine tests (serum calcium and uric acid levels, and urine volume, pH, calcium, oxalate, citrate, sodium, uric acid and cystine) were compared to the outcomes achieved with no metabolic testing following treatment as appropriate for any recurrent stones. Outcomes sought included stone recurrence and need for any intervention, the nature of any metabolic abnormality detected, Quality of life and Adverse events related to the tests or treatment [reported in the 36 page Evidence Review A, in which 933 articles were screened, but which none were of sufficient quality to be reviewed]. A formal research study to evaluate the clinical and cost effectiveness of a full metabolic assessment compared with standard advice alone in people with recurrent calcium oxalate stones was recommended. Following comments in the review process, the guidelines have recommendation that serum calcium should be checked, and biochemical stone analysis considered.

In addition to these individual topic reports, a 49 page evidence review summaries the research methodology and provides an extensive glossary of terms, and a 73 page “Costing analysis of surgical treatments” provides the information regarding the cost effectiveness of the treatments, such as the estimates that 1000 URS procedures and follow up would cost £3,328,895 compared with £961,376 for 1000 ESWL treatments and follow up.

In conclusion, the NICE Guideline Renal and ureteric stones: assessment and management (NG118) is a 33 page summary of over 1700 pages of evidence and analysis. It is therefore an example of where the parts are very much greater than the sum: there is an enormous wealth of high quality data presented in the eleven Evidence Reviews, which are like individual handbooks of contemporary stone management, almost exclusively based on Level 1 Randomised Controlled Trial Evidence. At a time when Brexit dominates national and international news, this is a British Export that we can be proud of.

The real test, of course, will be in the delivery of these ideals, and it is likely that the goal of treating symptomatic patients with ureteric stones within 48 hours will be difficult to achieve. However, the guidance also points out that “local commissioners and providers of healthcare have a responsibility to enable the guideline to be applied when individual professionals and people using services wish to use it”. Along with the GIRFT report, the NICE guidelines are key drivers for change not just in the way that stone patients are managed by their urologist, but in the way that they are treated by the system. Who does not want to be able to treat a patient in pain, with a definitive intervention (be it ESWL or URS) within 48 hours, and without the need for a stent for either the patient or Urologist to worry about. That is the goal that these guidelines have set us; achieving that would be something that Endourologists can be very proud of, and our patients will be extremely grateful for. Are we up for the challenge?

DS

London, January 2019

Jonathan Glass Commentary

The NICE Stone Guidelines – clarification or confusion?

‘This guideline covers assessing and managing renal and ureteric stones.

It aims to improve the detection, clearance and prevention of stones, so reducing

pain and anxiety, and improving quality of life’.

This is the opening paragraph of the recently produced NICE guidelines on the management of urinary tract stones. The guidelines have been produced in the context of existing guidelines produced by the European Association of Urology and the American Urological Association pre-existing, and one hoped that these guidelines would add something for the treatment of stone disease in the UK to justify the expenditure spent producing them. I write these comments in full recognition of the terms of reference to which NICE adheres in producing a set of guidelines.

I, with other members of the committee of the Section of Endourology of BAUS wrote a response to the draft guidelines and we are delighted that the committee has changed some aspects of the published guidelines as a result of our (and other contributions) to the consultation process. I must record however that what follows is a personal opinion, and not that of the committee.

These guidelines do refer to patients with a single stone. That of course immediately means that they have limited application to many of our patients who have multiple stones at first presentation.

The draft guidelines, which are in the public domain, stated ‘Do not use opioids’ in the treatment of ureteric colic. Although this has been changed to ‘Do not offer opioids to adults, children and young people with suspected renal colic unless both NSAIDs and intravenous paracetamol are contraindicated or have not been effective’ this still potentially leaves patient in severe pain for too long. Our first duty as doctors is to relieve pain. In my view, as a doctor caring for stone patients but also as an individual who has suffered ureteric colic, if opioids are needed, they should be given in a timely manner.

The recommendations on medical expulsive therapy are unusual at best and arguably a little bizarre and confusing to the British urologist. There is good evidence from a large UK study – the SUSPEND trial – that alpha blockers have little role to play in improving stone passage. This is the best level 1 evidence in the use of alpha blockers in stone disease. The study was sponsored by the NIHR and as such was truly independent, was statistically robust, and randomised. A representation was made to the guidelines committee by the Aberdeen group that published the study following distribution of the draft guidelines pointing out the robust nature of their study and the less than robust nature of the studies that made up the meta-analysis from which the guideline was derived. I would suggest that this guideline puts British urologists in a situation of huge uncertainty about how we advise our patients in this regard. Do we tell our patients the best evidence shows one course of action – not to use alpha blockers, but the NICE guidelines suggest another path? (I am pleased however that the administration of nifedipine, the use of which appeared in the draft guidelines, was removed from the final document).

The recommendation about pre-stenting children with staghorn stones prior to lithotripsy is arguably an historical perspective. Children with staghorn stones should be considered for primary percutaneous surgery. The recommendation in the guideline possibly reflects review of papers in a field where treatments and approaches to care have changed considerably in the last 10 years. I recognise that robust level 1A evidence is lacking for these interventions. It could indeed be argued that a guideline stating ‘consider ESWL, ureteroscopy or PCNL’ for stones 10-20mm and for stones greater than 20mm or staghorn stones is of limited use. Complex patients require bespoke care individualised to the patient in front of the clinician, taking in to account the stone and all other factors with respect to the patient other than the stone.

Suggesting treatment within 48 hours of presentation of patients with ureteric stones including lithotripsy will put urologists under huge pressure. Patients could hold up these guidelines and demand care. Treatment within 48 hours is often unnecessary, has huge cost implications, may well be unachievable and could lead to excessive intervention. To introduce it successfully, given that most stones present to district general hospitals, would suggest that NICE is calling for a lithotripter in every DGH, and in so doing, suggests the death of the mobile lithotripsy service; alternatively it will require the rapid and streamlined transfer of patients to stone centres for intervention. Either way the cost implications of this are considerable. I am certainly an advocate for the clinically appropriate timely treatment of stone patients but producing guidelines that are possibly unrealistic and impossible to implement might be considered a missed opportunity.

The recommendation to not offer routine stenting to patients undergoing ureteroscopy is controversial. As clinicians we understand the symptoms caused by stents. We also know the risk of sepsis following any stone intervention, the pain from stones obstructing the ureter and the oedema generated by ureteroscopy in the unstented ureter. Sepsis from urological disease is life threatening. These guidelines allow the legal justification of leaving a ureter unstented post ureteroscopy. I don’t know and can’t always predict which patients are going to go septic post intervention. Stents in this scenario save lives but proving that with level 1A evidence is nigh on impossible. I have concerns that this recommendation is potentially harmful and may be dangerous. We accept that many patients have interventions and procedures that may appear unnecessary to protect the few where it is life saving. This is true of nasogastric tubes following major surgery, of patients having a radical prostatectomy, of the placement of the nephrostomy tube following percutaneous surgery. It is also true of stents after ureteroscopy.

The metabolic considerations are a little odd. Sending the stone for analysis is only something that should be considered in these guidelines, and yet recommendations are made – based on the stone analysis. Similarly, there are no recommendations for metabolic testing beyond taking a serum calcium, and yet treatments are recommended for patients with hypocitraturia or hypercalciuria with no suggestion when and in whom these conditions should be sought and diagnosed.

Is this an opportunity lost? Do these recommendations justify the considerable cost in time and money that NICE has put in? Are these guidelines potentially harmful – and will they result in the justification of stones not being sent for analysis, the inappropriate use of alpha blockers, obstructed infected kidneys after ureteroscopy and a serum creatinine never being sent.

I have a healthy scepticism for medicine by committee. The MDT discusses treatments for prostate cancer and makes recommendations without the patient being present. I am not sure this process has relieved me of my scepticism. ‘This guideline… aims to improve the detection, clearance and prevention of stones, so reducing pain and anxiety, and improving quality of life’. Read them, and decide for yourselves whether these aims have been met and the expense producing them justified.

JG

London, January 2019

Alpha‐blockers for uncomplicated ureteral stones: a clinical practice guideline

M Vermandere, T Kuijpers, J S Burgers, I Kunnamo, J van Lieshout, E Wallace, J Vlayen, E Schoenfeld, R A Siemieniuk, L Trevena, X Zhu, F Verermen, B Neuschwander, P h Dahm, K A O Tikkinen, K Aubrey‐Bassler, R W M Vernooij, B Aertgeerts, G E Bekkering

Abstract

Background

The role of medical expulsive therapy for uncomplicated ureteral stones remains controversial in light of new contradictory trial evidence. A Cochrane review was recently published to summarize the current best evidence on this topic.

Aim

To develop an evidence‐based recommendation concerning the use of alpha‐blockers for uncomplicated ureteral stones, based on an up‐to‐date Cochrane review.

Method

We applied the Rapid Recommendations approach to guideline development, which represents an innovative approach by an international collaborative network of clinicians, researchers, methodologists and patient representatives seeking to rapidly respond to new, potentially practice‐changing evidence with recommendations developed according to standards for trustworthy guidelines.

Results

The panel suggests the use of alpha blockers in addition to standard care over standard care alone in patients with uncomplicated ureteral stones (weak recommendation based on low quality evidence). The panel judged that the net benefit of alpha‐blockers was small and that there was considerable uncertainty about patients’ values and preferences. This means that the panel expects that most patients would choose treatment with alpha‐blockers but that a substantial proportion would not. This recommendation applies to both patients in whom the presence of a ureteral stones is confirmed by imaging as well as patients in whom the diagnosis is made based on clinical grounds only.

Conclusion

The Rapid Recommendations panel suggests the use of alpha‐blockers for patients with ureteral stones. Shared decision‐making is emphasized in making the final choice between the treatment options.

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

Residents’ Podcast: CUA 2018 review

Jesse Ory and Andrea Kokorovic

Department of Urology, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS, Canada

Dalhousie residents Jesse Ory and Andrea Kokorovic sum up the highlights of day 1 at the 2018 Canadian Urological Association annual meeting in Halifax

Song credits

Don’t fear the reaper: Blue oyster cult

Mute city: F Zero

Mortal Kombat Theme: The Immortals

Funky Suspense – Bensound.com

BJUI Podcasts now available on iTunes, subscribe here https://itunes.apple.com/gb/podcast/bju-international/id1309570262

Article of the Week: NICE Guidance ‐ Complicated UTIs: ceftolozane/tazobactam

Every Week, the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Week from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

If you only have time to read one article this week, it should be this one.

NICE Guidance ‐ Complicated urinary tract infections: ceftolozane/tazobactam

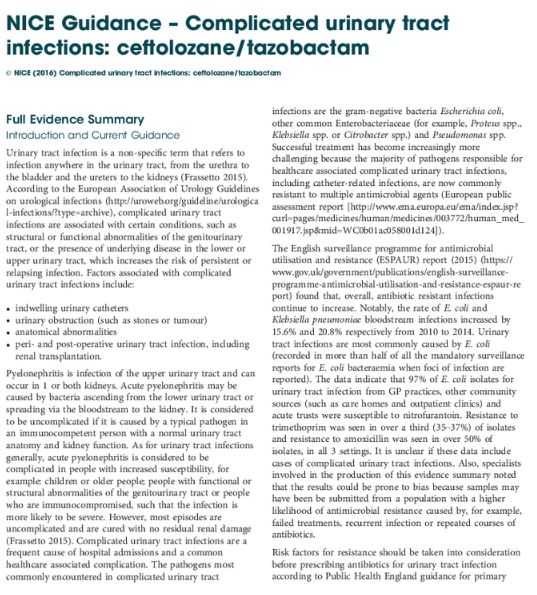

Introduction and Current Guidance

Urinary tract infection is a non‐specific term that refers to infection anywhere in the urinary tract, from the urethra to the bladder and the ureters to the kidneys. According to the European Association of Urology Guidelines on urological infections (https://uroweb.org/guideline/urological-infections/?type=archive), complicated urinary tract infections are associated with certain conditions, such as structural or functional abnormalities of the genitourinary tract, or the presence of underlying disease in the lower or upper urinary tract, which increases the risk of persistent or relapsing infection. Factors associated with complicated urinary tract infections include:

- indwelling urinary catheters

- urinary obstruction (such as stones or tumour)

- anatomical abnormalities

- peri‐ and post‐operative urinary tract infection, including renal transplantation.

Pyelonephritis is infection of the upper urinary tract and can occur in 1 or both kidneys. Acute pyelonephritis may be caused by bacteria ascending from the lower urinary tract or spreading via the bloodstream to the kidney. It is considered to be uncomplicated if it is caused by a typical pathogen in an immunocompetent person with a normal urinary tract anatomy and kidney function. As for urinary tract infections generally, acute pyelonephritis is considered to be complicated in people with increased susceptibility, for example: children or older people; people with functional or structural abnormalities of the genitourinary tract or people who are immunocompromised, such that the infection is more likely to be severe. However, most episodes are uncomplicated and are cured with no residual renal damage. Complicated urinary tract infections are a frequent cause of hospital admissions and a common healthcare associated complication. The pathogens most commonly encountered in complicated urinary tract infections are the gram‐negative bacteria Escherichia coli, other common Enterobacteriaceae (for example, Proteus spp., Klebsiella spp. or Citrobacter spp.) and Pseudomonas spp. Successful treatment has become increasingly more challenging because the majority of pathogens responsible for healthcare associated complicated urinary tract infections, including catheter‐related infections, are now commonly resistant to multiple antimicrobial agents (European public assessment report [https://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/medicines/human/medicines/003772/human_med_001917.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058001d124]).

The English surveillance programme for antimicrobial utilisation and resistance (ESPAUR) report (2015) (https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/english-surveillance-programme-antimicrobial-utilisation-and-resistance-espaur-report) found that, overall, antibiotic resistant infections continue to increase. Notably, the rate of E. coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae bloodstream infections increased by 15.6% and 20.8% respectively from 2010 to 2014. Urinary tract infections are most commonly caused by E. coli (recorded in more than half of all the mandatory surveillance reports for E. coli bacteraemia when foci of infection are reported). The data indicate that 97% of E. coli isolates for urinary tract infection from GP practices, other community sources (such as care homes and outpatient clinics) and acute trusts were susceptible to nitrofurantoin. Resistance to trimethoprim was seen in over a third (35–37%) of isolates and resistance to amoxicillin was seen in over 50% of isolates, in all 3 settings. It is unclear if these data include cases of complicated urinary tract infections. Also, specialists involved in the production of this evidence summary noted that the results could be prone to bias because samples may have been be submitted from a population with a higher likelihood of antimicrobial resistance caused by, for example, failed treatments, recurrent infection or repeated courses of antibiotics.

Risk factors for resistance should be taken into consideration before prescribing antibiotics for urinary tract infection according to Public Health England guidance for primary care on managing common infections (https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/managing-common-infections-guidance-for-primary-care).

As well as some other groups, Public Health England advises performing culture and sensitivity testing in people with a higher risk of recurrent urinary tract infection (such as those aged over 65 years or with urinary catheters), and people with abnormalities of the genitourinary tract or suspected pyelonephritis.

The management of suspected community‐acquired bacterial urinary tract infection in adults aged 16 years and over is covered in the NICE quality standard on urinary tract infection in adults (https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs90). This includes women who are pregnant, people with indwelling catheters and people with other diseases or medical conditions such as diabetes. The guidance was developed to contribute to a reduction in emergency admissions for acute conditions that should not usually require hospital admission, and improvements in health‐related quality of life. It does not make any recommendations around antibiotic treatment of complicated urinary tract infection, but includes 7 statements that describe high‐quality care for adults with urinary tract infection.

This evidence summary outlines the best available evidence for a new antimicrobial that is licensed for complicated urinary tract infections and acute pyelonephritis, ceftolozane/tazobactam. Ceftolozane/tazobactam was developed to address antimicrobial resistance in serious infections caused by gram‐negative pathogens.

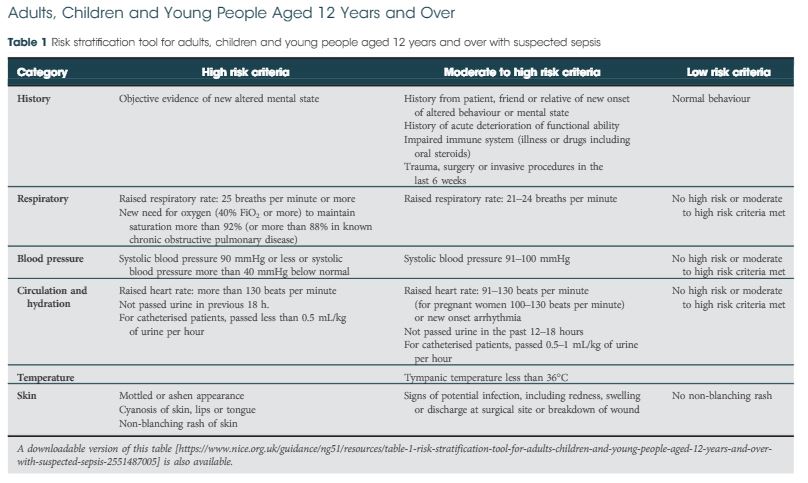

Article of the Week: NICE Guidance. Sepsis – recognition, diagnosis and early management

Every Week, the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Week from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

If you only have time to read one article this month, it should be this one.

Sepsis: recognition, diagnosis and early management

Overview

This guideline covers the recognition, diagnosis and early management of sepsis for all populations. The guideline

committee identified that the key issues to be included were: recognition and early assessment, diagnostic and prognostic value of blood markers for sepsis, initial treatment, escalating care, iden tifying the source of infection, early monitoring, information and support for patients and carers, and training and education.

Who is it For?

•People with sepsis, their families and carers.

•Healthcare professionals working in primary, secondary and tertiary care. Recommendations

People have the right to be involved in discussions and make informed decisions about their care, as described in

your care [https://www.nice.org.uk/about/nice-communities/public-involvement/your-care].Making decisions using NICE guidelines [https://www.nice.org.uk/about/what-we-do/our-programmes/nice-guidance/nice-guidelines/using-NICE-guidelines-to-make-decisions] explains how we use words to show the strength (or certainty) of our recommendations, and has information about prescribing medicines (including off-label use), professional guidelines, standards and laws (including on consent and mental capacity), and safeguarding.

More Information

You can also see this guideline in the NICE pathway on sepsis [https://pathways.nice.org.uk/pathways/sepsis].

To find out what NICE has said on topics related to this guideline, see our web page on infections [https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/conditions-and-diseases/infections]. See also the guideline committee’s discussion and the evidence reviews (in the full guideline [https://www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/NG51/evidence]), and information about how the guideline was developed [https://www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/NG51/documents], including details of the committee. Recommendations for Research The guideline committee has made the following recommendations for research.

© NICE (2017) Sepsis: recognition, diagnosis and early management