We report a case of solitary primary paraganglioma in the paratesticular region, presenting with scrotal swelling and dull pain as the only symptoms.

Authors: Dr. Sufia Husain MBBS, MD, FRCPath, Senior Registrar (Histopathology Unit). Dept of Pathology

Dr. Emad Raddaoui MD, FCAP, FASC, Consultant Histopathologist (first author), King Khalid University Hospital, College of Medicine, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Corresponding Author: Dr. Sufia Husain MBBS, MD, FRCPath, Senior Registrar (Histopathology Unit). Dept of Pathology, P.O. Box 2925, King Khalid University Hospital, College of Medicine, King Saud University, Riyadh-11472, Saudi Arabia. Tel: 00-9661-4671892. Email: sufiahusain@hotmail.com

Introduction

Paraganglia are aggregates of neuroendocrine cells, distributed throughout the body. Paragangliomas are unique neuroendocrine neoplasms arising from these specialized cells of neural crest origin. These tumours are usually located in the carotid body, the jugulo-tympanic body, the mediastinal vessels, or the abdomen, with the majority being benign. Although they have been described in virtually every organ, a paraganglioma at a paratesticular location is extremely rare. Only 8 cases have been reported to date. The clinical features of these tumours are variable, including hypertension, palpitations, headache, sweating, and other symptoms associated with increased catecholamine levels. We report a case of solitary primary paraganglioma in the paratesticular region, presenting with scrotal swelling and dull pain as the only symptoms. We also review in brief the clinical differential diagnosis, possible histogenesis, light microscopic features, immunohistochemistry and electron microscopy results, and general prognosis of the tumour.

Case report

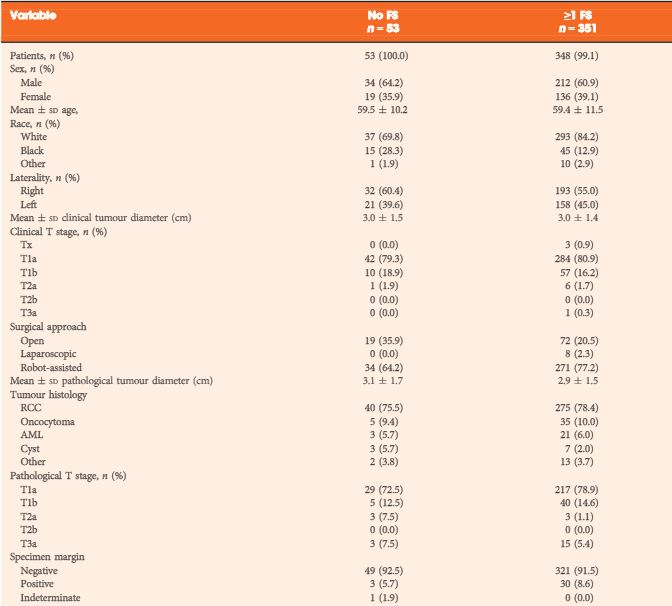

A 35-year-oldSaudi man presented with an 11-month history of dull ache and dragging sensation in the scrotum, accompanied by a scrotal swelling. There was no history of fever, genital trauma, or genital infection. The patient denied having experienced nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, flushing, palpitations, or weight loss. His vital signs were normal, and the findings of a general physical examination were unremarkable. Examination of the scrotum revealed a right-sided non-tender mass with 3.0 cm being its largest diameter. There were no changes in the overlying skin, and no enlargement of the inguinal lymph nodes. The left side of the scrotum was normal. The complete blood count was normal, as were the levels of tumour markers such as alphafetoprotein, beta human chorionic gonadotrophin, and lactate dehydrogenase. Ultrasonography performed to further define the mass showed a well-circumscribed right paratesticular mass at the upper poleof the right testis, near the head of the epididymis. There was an associated mild varicocoele. The lesion did not involve the epididymis and testis. The right and left testicles were normal in size and echotexture. A chest radiograph and abdominal computed tomography scan showed no significant abnormalities. A provisional clinical diagnosis of a benign paratesticular mass was made, and the patient was counseled before exploratory surgery was performed under general anaesthesia. Tissue from the lesion was submitted for intra-operative frozen section pathologic analysis to enable a decision about testicular preservation. When the specimen was reported as a benign soft tissue tumourwith features consistent with paraganglioma, a testis-sparing operation was chosen. The mass was subsequently excised, but the right testicle and epididymis were not resected. Postoperative recovery was uneventful. The patient was discharged 5 days after surgery, with instructions for regular periodic follow-up with the urologist.

The specimen received in the laboratory was a well-encapsulated mass measuring 3.0 × 2.5 × 2.0 cm. Its external surface was smooth and slightly lobulated, with thin-walled blood vessels running across it. The cut surface was solid and yellowish with focal haemorrhagic areas and delicate septae coursing through it. The tissue was fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin. Multiple sections were taken from the tissue and embedded in paraffin, cut into 5 micron thick slices, transferred to slides, and stained with haematoxylin and eosin. Unstained slides were also prepared for immunohistochemical study. Light microscopy revealed a tumour comprising cohesive lobules or nests of cells bound by delicate fibrovascular stroma arranged in a Zellballen pattern (Fig.1a). These nests of tumour cells were peripherally encircled by spindle-shaped sustentacular cells. The tumour cells were round to oval with abundant granular eosinophilic cytoplasm, speckled nuclear chromatin, and conspicuous nucleoli. The cells showed mild to moderate nuclear pleomorphism. Scattered multinucleated giant cells were present. Features like intracytoplasmic hyaline globules and eosinophilic intranuclear pseudoinclusions (Fig.1b) were also noted. Mitotic activity, although present, was no more frequent than 1 mitotic figure per 20 high power fields. Necrosis and lymphovascular invasion were absent.

The unstained slides were subjected to immunohistochemical analysis in the Leica Bond Max immunostainer (Vision BioSystems, Newcastle, UK) using the Bond Polymer Refine detection kit (a biotin-free, polymeric horseradish peroxidase-linker antibody conjugate system). The tissue was stained using antibodies against S-100, chromogranin, synaptophysin, CD 56, cytokeratin (CK), and vimentin. The tumour cells exhibited diffuse cytoplasmic positivity forsustentacular cells labeled with chromogranin (Fig.1c), synaptophysin, and CD 56. The sustentacular cells were labeled with S-100;therewere stellate and spindle-shaped cells found cuffing the Zellballen nests (Fig.1d). The tumour cells did not react with CK or vimentin. The Ki67/MIB-1 index was less than 2%.

Figure 1. (a) Photomicrograph showing a low power view of the tumor mass, exhibiting the classical nesting pattern called Zellballen architecture (hematoxylin-eosin, 200× magnification). (b) A higher magnification of the tumor shows cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and moderate nuclear pleomorphism. An intranuclear pseudoinclusion (arrow) is also noted (hematoxylin-eosin, 400× magnification). (c) The tumor cells reveal strong cytoplasmic positivity for chromogranin (400× magnification). (d)The sustentacular cells rimming the Zellballen nests are highlighted by the S-100 stain (400× magnification).

A small amount of paraffin-embedded tissue was submitted to the electron microscopy unit. On ultrastructural evaluation, numerous small dense secretory cytoplasmic granules measuring approximately 150 microns were identified (Fig. 2). The light microscopic, immunohistochemical, and electron microscopic features were thus all characteristic of paraganglioma. The absence of any other lesion elsewhere in the body, both clinically and radiologically, led to a final diagnosis of primary paratesticular paraganglioma.

Figure 2a and 2b. FIG. 2(a) Electron micrograph showing the characteristic multiple dark neurosecretory granules (black arrow) in the cytoplasm of the tumor cells. These are membrane-bound granules with an electron-dense core. (transmission electron microscope, 9000× magnification). (b) The neurosecretory granules are seen around the nucleus at a higher magnification. Also visible, is the rough endoplasmic reticulum (arrowhead) (transmission electron microscope, 28000× magnification).

Discussion

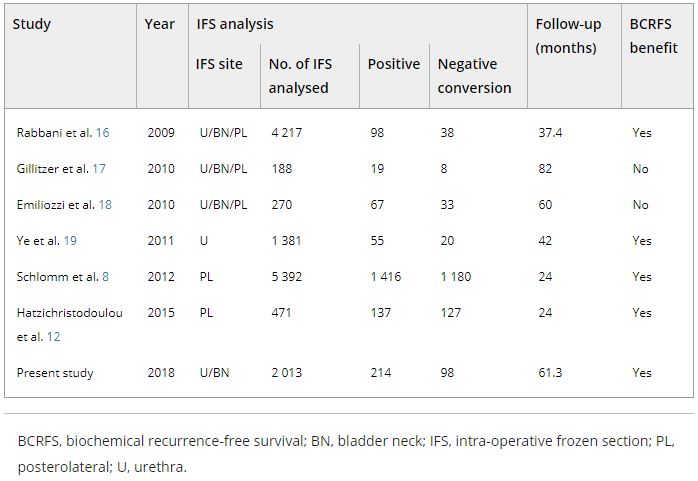

Scrotal paratesticular masses present a diagnostic dilemma to urologists. most paratesticular tumours are benign, about 30% are malignant [1]. Any scrotal mass therefore has to be adequately evaluated in order to rule out malignancy. Exploratory surgery with intraoperative histologic analysis of a frozen section is useful in surgical decision-making. Once the benign nature of the neoplasm is determined on frozen section, a testis-sparing surgical procedure can be performed, with the benefits of retaining the cosmetic and hormonal function of the organ. Common benign tumours of the paratesticular region include lipomas, adenomatoid tumours, leiomyomas, fibromas, papillary mesotheliomas, and cystadenomas [1]. Paragangliomas are extraordinarily rare at this site.

Paragangliomas are neuroendocrine neoplasms of neural crest origin composed of neuroepithelial chief cells. They occur in the fourth and fifth decades and are equally prevalent in both sexes [2]. Most paragangliomas are located in the adrenal gland, where they are referred to as pheochromocytomas. Extra-adrenal paragangliomas are found along the sympathetic and parasympathetic chains, where paraganglia are normally distributed. The common sites for extra-adrenal paragangliomas include the carotid body, vagal body, middle ear, abdomen (organ of Zuckerkandl), and the aortic-pulmonary and laryngeal areas [2].They have also been reported in certain unusual sites like the orbit [3], chambers of the heart, [4] and bone [5]. Paragangliomas have occasionally been reported in the urogenital tract, in the urinary bladder[6], and the prostate [7]. To our knowledge, only 8 cases have been reported worldwide in theliterature so far [8,9], with the first documented case of paratesticular paraganglioma described in 1971 by Eusebi et al. [10].

The histogenesis of paratesticular paragangliomas is a matter of debate. Paraganglia have been observed in the paratesticular tissue around the epididymis and spermatic cord in infancy [11, 12]. Rarely, heterotopic adrenal glands with medullae have also been documented along the route of descent of the testis into the scrotum [11,12]. As a rule, both the heterotopic gland and paraganglial tissue involute during childhood. In exceptional cases, they may persist and eventually harbour a neoplasm. It is our hypothesis that this may be the case in our patient.

These lesions can be functional or non-functional. In a functional lesion, the tumour secretes catecholamines and the presenting symptoms such as headache, sweating, palpitations, and hypertension are secondary to elevated levels of these hormones. Abdominal paragangliomas are more likely to be functional. Although our patient was not tested for catecholamine levels prior to surgery, his was clearly a case of a non-functional paraganglioma, since he displayed none of the symptoms associated with elevated catecholamines. Paragangliomas can also be hereditary or be seen in conjunction with neurofibromatosis type I, Von Hippel-Lindau disease, and multiple endocrine neoplasia type II. Our case had no such associations.

Most paragangliomas are benign, indolent tumours. Malignant lesions are rare, occurring in the fifth to seventh decade, and they tend to be more symptomatic than benign tumours. The diagnosis of malignancy is essentially based on the presence of distant metastasis. Capsular or lymphovascular invasion, a diffuse pattern, confluent tumour necrosis, atypical mitosis, increased mitotic activity (>3 mitotic figures/10 high power fields), fewer S-100 protein-positive sustentacular cells, and a high Ki-67 (MIB-1) index have all been postulated as indicators for predicting malignancy [2]. These indicators, however, are not reliable and cannot be used as well-established histologic criteria for malignancy. Therefore, the treatment of choice for a paraganglioma is complete surgical resectioncoupled with prolonged regular follow-up to rule out a recurrence or the development of metastases. Although there is no specific recommended follow-up strategy, our patient underwent 6 monthly follow-up examinations for the first 3 years and annual ones in the following 2 years. There was no clinical, biochemical, or radiological evidence of recurrence or metastases of the tumour in the 5 years after surgery.

In conclusion, we report a very rare case of non-functional primary paratesticular paraganglioma. We believe that despite their rareincidence in this region, they ought to be considered in the differential diagnosis of a paratesticular neoplasm. Radiological imaging alone is insufficient to determine the nature of a paratesticular mass. Scrotal exploration coupled with intraoperative frozen section analysis can be used as diagnostic tools to rule out the possibility of malignancy, and thus prevent overtreatment with orchidectomy. A diagnosis of paraganglioma is ultimately dependent on a complete and careful histopathological evaluation, in conjunction with consideration of the immunohistochemical findings. Electron microscopy can also be used to confirm the neuroendocrine nature of the neoplasm.

References

1. Khoubehi B, Mishra V, AliM, Motiwala H, Karim O. Adult paratesticulartumours. BJU International 2002;90:707-15.

2. Hunt J. Diseases of the paraganglia system.In: Thompson LDR, editor.Endocrine Pathology. In: Goldblum JR, series ed. Foundations in Diagnostic Pathology. 1st edn. Philadelphia, Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2006. p. 327-8.

3. Makhdoomi R, Nayil K, Santosh V, Kumar S. Orbital paraganglioma- a case report and review of literature. Clinical Neuropath. 2010 Mar-Apr;29(2):100-4.

4. Khalid TJ, Zuberi O, Zuberi L, Khalid I. A rare case of cardiac paraganglioma presenting as anginal pain: A case report.Cases J. [serial on the internet]. 2009 Jan 21; 2(1): [about 4 p.]. Available from:https://www.casesjournal.com/content/2/1/72.

5. Laufer I, Edgar MA, Hartl R. Primary intraosseous paraganglioma of the sacrum: a case report. Spine J. 2007; 7(6): 733-8.

6. Cheng L, Beltran AL, MacLennan GT, Montironi R, Bostwick DG.Neoplasms of the urinary bladder. In Bostwick D, Liang C,editors.Urologic Surgical Pathology, 2nd edn. Edinburgh: Mosby, Elsevier; 2008. P. 315-7.

7. Bostwick DG, Meiers I. Neoplasms of the prostate. In Bostwick D, Liang C, editors.Urologic Surgical Pathology, 2nd edn. Edinburgh: Mosby, Elsevier; 2008.p. 538.

8. Gupta R, Howell RS, Amin MB. Paratesticular paraganlioma: A rare cause of an intrascrotal mass. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009; 133(5): 811-3.

9. Garaffa G, Muneer A, Freeman A, et al. Paraganglioma of the spermatic cord: case report and review of the literature. Scientific World Journal 2008; 8: 1256-8.

10. Eusebi V, Massarelli G. Pheochromocytoma of the spermatic cord: report of a case. J Pathol. 1971; 105(4): 283-4.

11. Nistal M, Paniagua R. Non-neoplastic disease of the testis. In Bostwick D, Liang C, editors: Urologic Surgical Pathology, 2nd edn. Edinburgh: Mosby Elsevier; 2008. p. 622-3.

12. Petersen R, Sesterhenn IA, Davis CJ:Urologic Pathology, 3rd edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;2009. p. 413-4.

Date added to bjui.org: 17/05/2011

DOI: 10.1002/BJUIw-2011-036-web