Valentine’s Day PSA

A few years ago Barrack Obama, the President of the USA, is supposed to have said on Valentine’s Day – “Gentlemen – do not forget!”

A few years ago Barrack Obama, the President of the USA, is supposed to have said on Valentine’s Day – “Gentlemen – do not forget!”

He was apparently speaking “from experience”. Not remembering that important day can have catastrophic consequences for many men. On that occasion, PSA stood for public service announcement.

The headline, however, could easily have been mistaken for Prostate Specific Antigen. One could argue whether the PSA test is as important to men as Valentine’s Day. Most men probably do not bother, especially if they are less than 40 years old. The PSA debate swings around like a sine wave. Despite the best possible randomised controlled trials for and against PSA screening, there seem to be no clear answers with deep divisions amongst men and their urologists.

This February, the BJUI adds to the PSA debate by publishing the Melbourne Consensus Statement [1]. It was an attempt to bring some sense to a thorny subject. When published as a blog on www.bjui.org, most of our readers liked it, but certainly not all. The usual heated debate was inevitable. Earlier last summer Bal Carter, one of our BJUI Executive Members, chaired the AUA panel that recommended shared decision making for asymptomatic men between 55–69 years as far as PSA screening was concerned. They carefully analysed over 300 studies to make these recommendations [2]. I congratulated Bal on this milestone on the very morning this made headline news. However, such was the controversy that he had to present the findings twice – one appearance on the AUA podium was just not enough.

In a well-informed man, over diagnosis is not necessarily a problem as long as it does not lead to over treatment. I find myself treating a number of men in their 40s with strong family histories of prostate cancer. It is very difficult to deny them a PSA test when they seek it. This discussion is likely to become redundant in years to come when better risk stratification with genomic tools and improved imaging will complement the PSA test, rather than relying on it alone. In the meantime I leave it to our knowledgeable readers to make up their own minds.

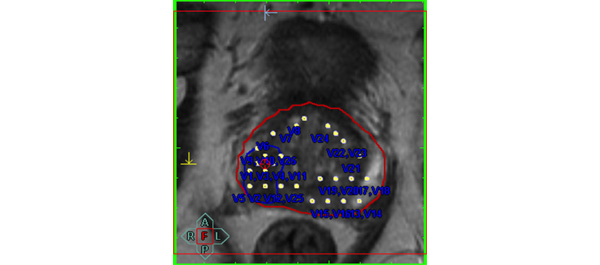

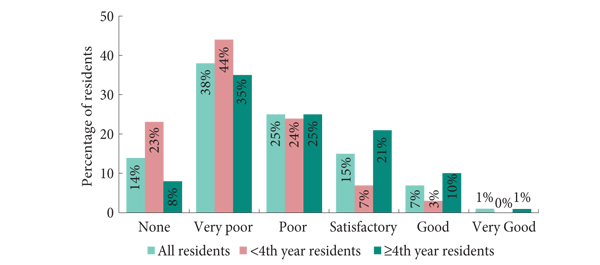

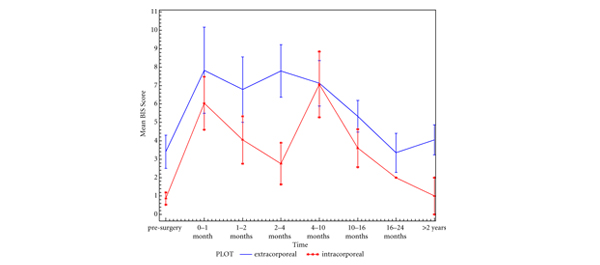

Not everyone is interested in the PSA test in the month of February. If you belong to this category, perhaps we could grab your attention with a multi-institutional collaborative study showing disease free and overall survival rates of over 90% following LESS partial nephrectomy, a challenging procedure, even for technically accomplished surgeons [3]. Khurshid Guru’s group also present data to show that urinary and bowel domains take about 6 months to recover after robotic cystectomy; sexual domains even longer [4].

I have no illusions that none of the above may be of the slightest importance to some readers. In which case you may wish to head to the best florist in town. Forget that at your peril …

Prokar Dasgupta, Editor in Chief, BJUI

Guy’s Hospital, King’s College London

References

- Murphy DG, Ahlering T, Catalona WJ et al. The Melbourne Consensus Statement on the Early Detection of Prostate Cancer. BJU Int 2014; 113: 186–188

- Carter HB. American Urological Association (AUA) Guideline on prostate cancer detection: process and rationale. BJU Int 2013;112: 543–547

- Springer C, Greco F, Autorino R et al. Analysis of oncological outcomes and renal function after laparoendoscopic single site partial nephrectomy: a multi-institutional outcome analysis. BJU Int 2014; 113: 266–274

- Poch MA, Stegemann AP, Rehman S et al. Short-term patient reported health-related quality of life (HRQL) outcomes after robot-assisted radical cystectomy (RARC). BJU Int 2014; 113: 260–265

The new year has arrived bringing with it new expectations of success. It gives us the opportunity to reflect on 2013 and plan for the year ahead. We hope you enjoyed the new web journal

The new year has arrived bringing with it new expectations of success. It gives us the opportunity to reflect on 2013 and plan for the year ahead. We hope you enjoyed the new web journal