Kim et al. [1] asked the question whether we should start by treating men who have persistent storage LUTS despite α-blocker monotherapy, with a low-dose anti-cholinergic as opposed to the standard dose (given the potentially increased risk of side-effects such as acute urinary retention and high discontinuation rates with the standard dose). It is a valid question, for we know that discontinuation rates with standard doses of anti-cholinergics can be as high as 50% in the first 3 months due to a combination of ineffectiveness and side-effects [2]. However, the problem lies in the multifactorial nature of the causes of storage vs voiding LUTS, and the difficulty in assessing and distinguishing them accurately with our current tools.

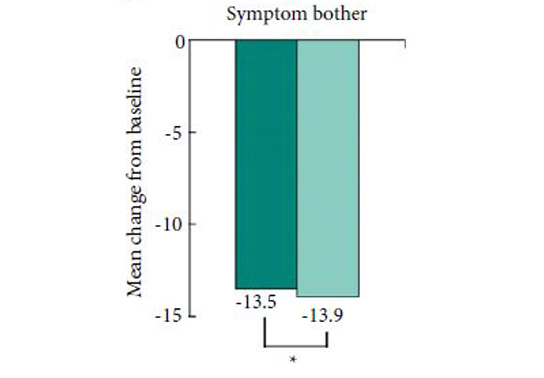

The authors have conducted a randomised controlled trial of 2 mg vs 4 mg tolterodine added to the participants’ on-going α-blocker regime and selected reduction in total IPSS as their primary outcome measure. They have also assessed IPSS sub-scores, 3-day bladder diary variables, and the Patient Perception of Bladder Condition (PPBC) and Overactive Bladder (OAB-q) questionnaires, as secondary outcomes. As would be expected of a peer-reviewed publication the trial has been seemingly well conducted and fairly well reported. Recruitment met the requirement set by the power calculation based on a clinically significant difference of a 4-point drop in total IPSS, and the authors concluded that 2 mg tolterodine is not inferior to the 4 mg dose in achieving a significant reduction in total IPSS at 12 weeks. They also report no difference in patient perception of treatment benefit or satisfaction at this time point.

These results are interesting, especially considering some of the details of the study. First of all, patients were not on the same α-blocker at baseline; the most common was tamsulosin (62.8%), but alfuzosin, doxazosin, and others were also being used. This in itself may not be a problem because all patients continued on the same α-blocker through the study, and in fact this better represents real-world practice. However, the mean (sd) duration of α-blocker therapy at baseline was 9.1 (19.9) months. We know that α-blocker therapy can improve IPSS by up to 30–40% [3], but the pertinent question for this study is whether these patients had achieved this level of improvement initially then stabilised and improved no further, or whether they had no improvement at all? It could conceivably make a difference to participants approach to the IPSS if they were previously familiar with it and, more importantly, aware of their results. The Hawthorne effect, also known as the observer effect, and the related Heisenberg uncertainty principle, are factors that we must necessarily encounter in clinical trials but we sometimes fail to account for.

Another aspect of the study that warrants consideration is the choice of primary outcome itself. This is a particular bug-bear of mine and indeed has been commented on by many authors including in the European Association of Urology (EAU) guideline on urinary incontinence in relation to anti-muscarinics [4]. Outcomes that lend themselves to easier power calculations and statistically significant results have almost evolved to be ‘un’-naturally selected for the purpose of clinical trial primary outcome measures. Drug trials are especially notorious for this. Here again, the choice of the total IPSS to assess whether an anti-muscarinic will help improve persistent storage LUTS is a case in point. Not least because it renders the significance of all the secondary outcomes dependant on the same power calculation. It is no doubt convenient, but is it appropriate? It is easy to point the finger at trialists for this, but the business-like, ‘bottom-line’ nature of medical publishing and research today is equally, if not more, to blame.

Finally, I would like to call the reader’s attention to the difference in baseline urgency and urgency urinary incontinence (UUI) episodes. The author’s state there was no statistically significant difference, but one might argue that when assessing improvement in storage LUTS, a group with a mean (sd) baseline number of UUI episodes of 3.9 (8.6) may perceive improvement quite differently compared with a group with a baseline of 1.6 (1.1). This has borne out in the difference in the bladder diary outcome of UUI/24 h; significant improvement in the first group (who were wetter at baseline and got 4 mg tolterodine) but no difference in the latter group (comparatively drier and got 2 mg tolterodine). But almost paradoxically this does not seem to have made a difference to the patient-reported outcome measures. One possible explanation for this could be the relatively few patients who were incontinent at baseline.Overall this paper gives us a lot of food for thought. The direct result – should we indeed start men with persistent storage LUTS on low-dose anti-cholinergics rather than standard dose, and then titrate upwards? But it also challenges us to consider whether we simply accept researcher’s and sponsor’s decisions on outcome measures. What do you think? Do we simply sit back and accept what is put before us because statistics scares us a little? Or, as researchers and consumers of medical literature, do we struggle to make the hard choices, risk our results being rejected by the top journals, and stand up for good science?

Conflicts of Interest

The author has received a travel grant to attend an international conference from Ferring pharmaceuticals.

Arjun K. Nambiar

Clinical Research Registrar

Department of Urology, Morriston Hospital, Abertawe Bro Morgannwg (ABM) University Local Health Board, Swansea, SA6 6NL, UK

References

1 Kim TH, Jung W, Suh YS, Yook S, Sung HH, Lee KS. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of tolterodine 2 mg and 4 mg combined with an a-blocker in men with lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and overactive bladder: a randomized controlled trial.

BJU Int 2015; 117: 307–153 Gravas S, Bach T, Bachmann A et al. Guidelines on Non-Neurogenic Male LUTS Including Benign Prostatic Obstruction, Section 3C.2. In: EAU Guidelines, edition presented at the 30th EAU Annual Congress, Madrid 2015. ISBN 978-90-79754-80-9. Available at:

https://uroweb.org/wp-content/uploads/11-Male-LUTS_LR.pdf. Accessed September 2015