In this issue of BJUI, Ward et al. [1] describe the development of DNA‐based urinary biomarkers for urothelial carcinoma (UC). The genomics of UC have been well characterized through interrogation of tumour issues in institutional series (e.g. the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center [MSKCC] experience), multi‐institutional collaborations (e.g. The Cancer Genome Atlas [TCGA]) and commercial platforms (e.g. the Foundation Medicine experience) [2]. Until recently, these have been largely academic pursuits, with possible impact on prognostication but limited clinical applicability and utility for therapy selection and monitoring of response; however, with the US Food and Drug Administration approval of erdafitinib several weeks ago, patients with advanced UC will routinely receive genomic assessment for FGFR2/3 mutation or fusion, the targets for this therapy [3]. In due time, it is anticipated that multiple other putative targets with associated therapies (e.g. ERBB2, CDKN2A), as well as potential predictive biomarkers, may also warrant testing.

The evolving landscape in advanced UC makes a non‐invasive biomarker particularly attractive. The authors of the present commentary have previously reported results from a series of 369 patients with advanced UC, demonstrating that genomic alterations in ctDNA could be identified in 91% of patients using a commercially available 73-gene panel [4]. More recently, Christensen et al. [5] assessed a cohort of 68 patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy for muscle‐invasive disease, demonstrating 100% sensitivity and 98% specificity for the detection of relapsed disease with a patient‐specific ctDNA assessment (sequenced to a median target coverage of 105 000×) after cystectomy. Impressively, the data also showed that the dynamics of ctDNA appeared to be more useful than pathological downstaging in predicting relapse.

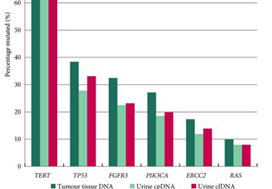

In contrast to these studies, Ward et al. have developed a 23‐gene panel based on frequently expressed genes in a cohort of 916 UC tissue specimens, largely derived from patients with non‐muscle‐invasive disease. Ultimately, with a cohort of 314 patients with DNA derived from a urinary cell pellet, sequencing identified 645 (71.4%) of 903 mutations detected in tumour. Using urinary supernatant, 353 (80.7%) of 437 mutations were detected. These relatively high sensitivities, if they can be interpreted as such, are promising but do not rise to the level of replacing existing strategies for UC detection, staging and monitoring. Notably, another study demonstrated that urinary ctDNA can be detected with high sensitivity and specificity in patients with localized early‐stage bladder cancer and for after‐treatment surveillance, providing the foundation for further studies evaluating the role of ctDNA in non‐invasive detection, genotyping and monitoring [6].

Beyond its use as a diagnostic tool, it is hoped that urinary ctDNA may also find applications in the selection of therapeutics. To this end, Ward et al. identified FGFR3, PIK3CA, ERCC2 and ERBB2 mutations in 45%, 32%, 14% and 7% of patients, respectively. The frequency of FGFR3 alteration decreased with increasing stage and grade, ranging from 72% in pTaG1 disease to just 13% in ≥pT2 disease, consistent with other reports [7]. These results may guide forthcoming studies evaluating FGFR inhibitors in non‐muscle‐invasive, muscle‐invasive and metastatic disease, where studies are ongoing. In reviewing the potential link between genomic alterations and clinical outcomes, perhaps the most curious finding is that between RAS mutations and improved overall survival (P = 0.04), the only such association found in multivariate analysis. These results stand in sharp contrast to reports in lung cancer, colorectal cancer and multiple other tumour types [8]. A closer look at the deleterious nature and functional impact of NRAS and KRAS mutations seen in this series is certainly warranted, along with further external validation in a more homogenous and larger patient population. There is also the potential application of monitoring treatment response by assessing eradication of urinary ctDNA, a hypothesis that is being evaluated in ongoing studies [9].

How will the results of this and other emerging urinary biomarker studies eventually make their way to the clinic? The answer is simple: incorporation of these biomarkers in prospective therapeutic trials. As the bladder cancer investigative community formulates novel trials for non‐muscle‐invasive and muscle‐invasive disease using targeted therapies, an excellent opportunity exists to correlate urinary, blood and tissue‐based biomarkers and to assess their relative predictive capabilities and clinical utility. Furthermore, with clinical surrogate endpoints likely to drive regulatory approval (e.g. landmark complete response rates for non‐muscle‐invasive disease, or pT0N0 rate for muscle‐invasive disease), a validated urinary biomarker could ultimately offer an alternative biological surrogate endpoint [10]. In an era of genomic revolution, prospective validation can help establish the potential clinical utility of promising biomarkers and help realize the dream of ‘precision oncology’.

by Rohit K. Jain, Petros Grivas and Sumanta K. Pal

References

- Ward DG, Gordon NS, Boucher RH et al. Targeted deep sequencing of urothelial bladder cancers and associated urinary DNA: a 23‐gene panel with utility for non‐invasive diagnosis and risk stratification. BJU Int 2019

- Schiff JP, Barata PC, Yu EY, Grivas P. Precision therapy in advanced urothelial cancer. Expert Rev Precis Med Drug Dev 2019; 4: 81– 93

- FDA grants accelerated approval to erdafitinib for metastatic urothelial carcinoma [press release] 2019.

- Agarwal N, Pal SK, Hahn AW et al. Characterization of metastatic urothelial carcinoma via comprehensive genomic profiling of circulating tumor DNA. Cancer 2018; 124: 2115– 24

- Christensen E, Birkenkamp‐Demtroder K, Sethi H et al. Early detection of metastatic relapse and monitoring of therapeutic efficacy by ultra‐deep sequencing of plasma cell‐free DNA in patients with urothelial bladder carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2019; 37: 1547– 57

- Dudley JC, Schroers‐Martin J, Lazzareschi DV et al. Detection and surveillance of bladder cancer using urine tumor DNA. Cancer Discov 2019; 9: 500– 9

- Tomlinson DC, Baldo O, Harnden P, Knowles MA. FGFR3 protein expression and its relationship to mutation status and prognostic variables in bladder cancer. J Pathol 2007; 213: 91– 8

- Zhuang R, Li S, Li Q et al. The prognostic value of KRAS mutation by cell‐free DNA in cancer patients: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. PLoS One 2017; 12: e0182562

- Abbosh PH, Plimack ER. Molecular and clinical insights into the role and significance of mutated DNA repair genes in bladder cancer. Bladder Cancer 2018; 4: 9– 18

- Jarow JP, Lerner SP, Kluetz PG et al. Clinical trial design for the development of new therapies for nonmuscle‐invasive bladder cancer: report of a Food and Drug Administration and American Urological Association public workshop. Urology 2014; 83: 262– 4