“It is not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent that survives. It is the one that is most adaptable to change…” (C. Darwin; ca.1857)

“It is not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent that survives. It is the one that is most adaptable to change…” (C. Darwin; ca.1857)

On Friday 18th March 2016, U.S. medical school students and graduates participated in the National Resident Matching Program (NRMP) with 42,370 registered applicants attempting to match into 30,750 PGY-1 and PGY-2 positions. This was preceded the same day by the Irish Higher Surgical Training (HST) Urology interview held in the RCSI in Dublin for a smaller number, but just as eager candidates endeavoring to secure their future in their own field. Thousands of candidates, in the pursuit of a career that they have so far, only dreamed about. Thousands of candidates, all with one thing in common: Not one of them knew where they were going to end up if they were somehow successful.

The British Medical Journal (BMJ) on their careers website explaining to core trainees how they might perform better in interviews, outline a roadmap of 12 key components from extra courses to leadership skills, but not once mention visiting the various deanery sites in order to assess whether the place represents a good fit for your own ambitions, learning objectives and style of management.

Prof. Adrian Joyce provided an editorial on the BJUI blogs site in 2013, highlighting the need to devise a better means of training “The UK conundrum shared with many other healthcare systems is how to provide effective training within the demands of service commitment and the EWTD… The challenge therefore is to devise innovative ways of training within the limit of fewer hours and training, not service, must become the priority for trainees and for those surgeons, departments and hospitals that train them…”

Therefore, we have two health systems on these islands, with the UK National Health Service (NHS), and the Irish Health Service Executive (HSE), both acknowledging the mandatory requirements of the European Working Time Directive (EWTD) to shorten working hours, and the need to fulfill service commitments within the health sector, and the need to allow for postgraduate training to ensure a steady workforce into the future, but also to balance the requirements of the Specialist Advisory Committee (SAC) and the Joint Commission on Surgical Training (JCST) as well as the Royal Colleges to ensure that training is to a satisfactory level. In order to achieve this, hospitals and trusts are allocated a number of trainees who have gone through the above selection process and have accumulated years of experience, qualifications and debts to fill a very complex role within a volatile system.

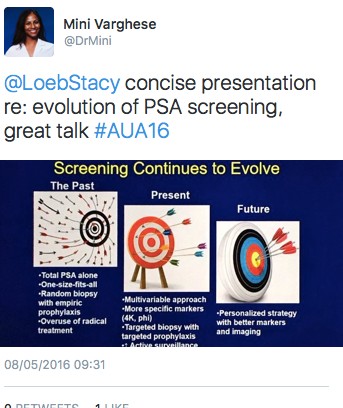

However, when did a “one-size-fits-all” approach become acceptable to trainers and trainees who need to work alongside each other within these environments filled with stress, litigation, and variable relationships with managerial types within the system? We all see patients, break bad news, manage expectations, provide treatment options, and above all know that each patient is different. They handle information, make choices, adhere and respond to treatment in a myriad of ways depending on a huge number of variables and confounders (not to mention the relatives). We have developed nomograms to try to communicate outcomes and risks to patients for disease like prostate cancer, such that entering the keywords “prostate cancer” and “nomogram” into PubMed will in excess of 900 hits. So, the hospital environment is complicated, and patients are complicated, but what about the lowly figure of the surgical trainee who has successfully demonstrated the aptitude and the background to progress to higher training?

Sullivan et al. demonstrated in 2013 that despite the reduction in trainee hours in the USA, resident attitudes, and program location were most frequently associated with voluntary attrition, with “the personal cost of training” (p<0.001; HR2.89) playing a major role in leaving a program. Bell et al. elegantly demonstrated in 2012 that despite the abundance of information on particular candidates, many of the fundamental qualities that are associated with success for the surgical trainee cannot be identified by review of the applicants’ grades, scores, letters of recommendation, personal statement, or even from the interview process. Therefor only by meeting trainees, in order to identify unique behavioral, motivational and personal talents that applicants bring to the program, allowed the authors to determine applicants who were a good match for the structure and culture of that particular program.

The standard interview process, whilst objective, does not allow trainers and institutions the luxury of getting a feel for the candidate, and applying instinct and acumen as to whether and how the trainee will fit into the overall scheme of things. The exact statement can be played in reverse.

All the innate instinctual abilities and skills that we prize in being able to quickly assess measure patients have been denied to us in choosing some of our closest junior colleagues on whom we rely on so heavily.

From a trainee urologist’s perspective, and one that would apply to nearly any other profession, one of the greatest predictors of your happiness and productivity at work is your relationship with your senior colleague. This is therefore intuitively important when considering new post, on order to know how you’ll get along with your new boss. This can be hard to assess in an interview when one is attempting to masquerade an unbridled sympathetic response and trying to demonstrate one’s one appointability, but it’s crucial to evaluate the panel as well. What sorts of questions should you ask to understand their management style? Should one try to talk with other people who have previously rotated through the post? Are there red flags you should watch out for? Will it even matter?

There are a number of healthy checklists in the business world which lend themselves to translation in surgery:

- Trust your instincts: Ask yourself whether this is the training post you want and the consultant you want to work for. Did you get a good feeling from the person? Is she someone you can imagine going to with problems? Or someone you could have a difficult conversation with? This is especially important when the stakes are high

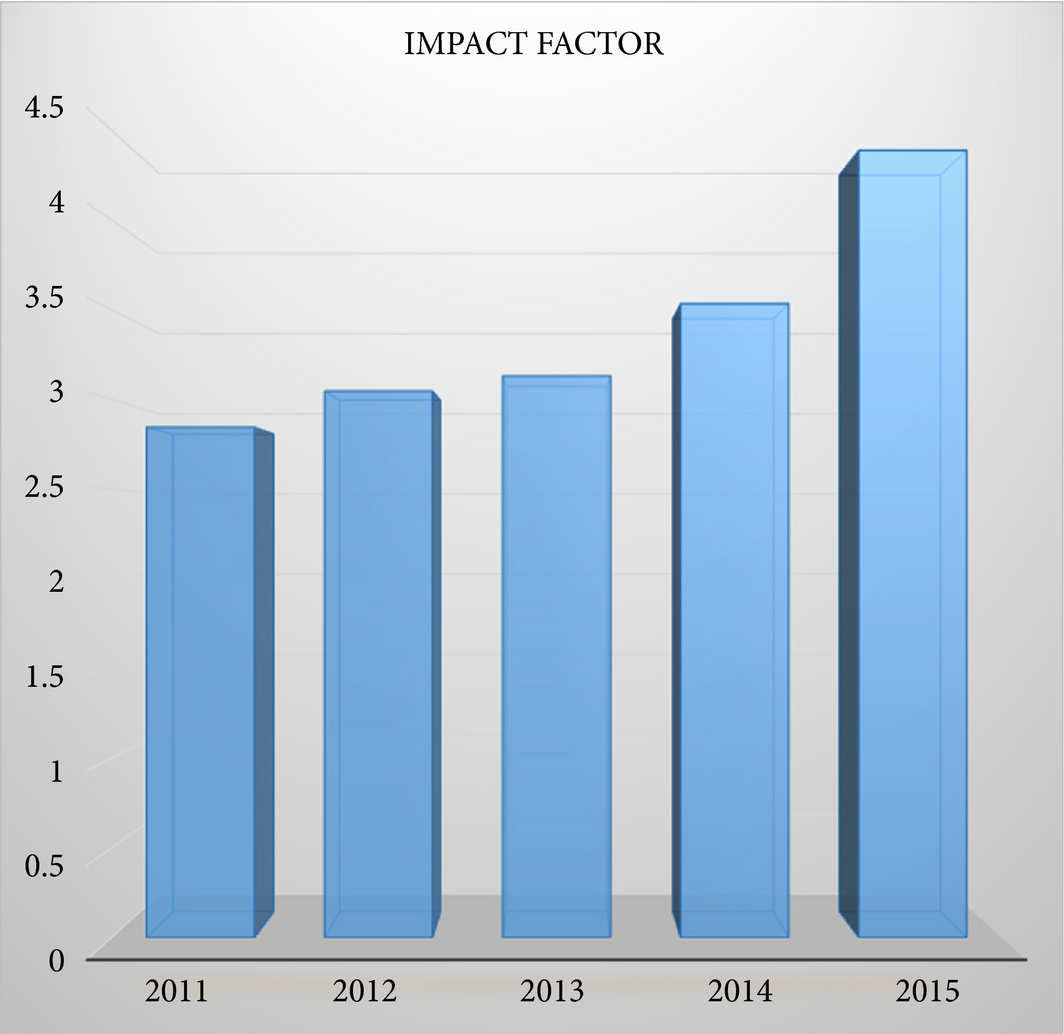

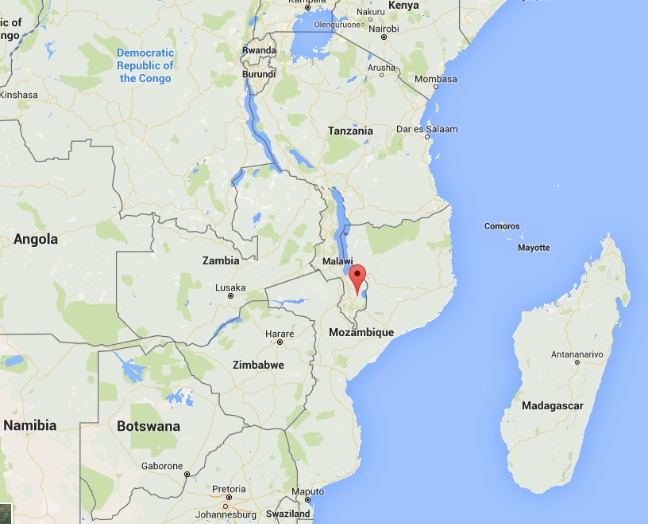

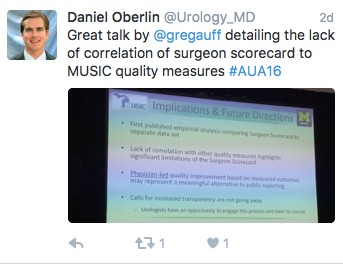

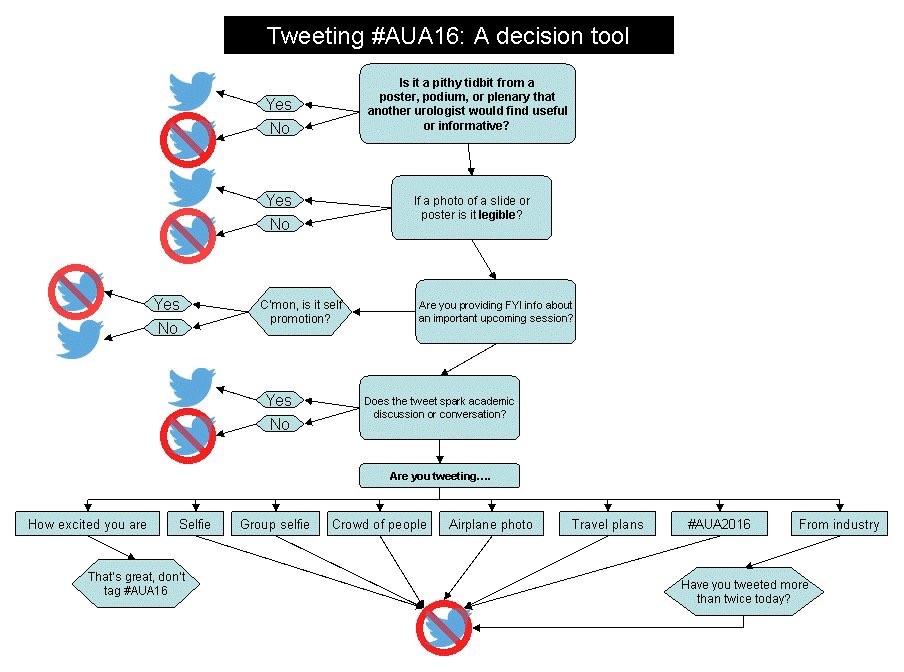

- Do your homework: One of the greatest faux pas one can make is to incompletely prepare. You should try to gather as much information on the unit/post as possible including the history of the department, publishing record of the consultants, theatre logbooks from other trainees, inter-personal relationships, red flags. Google each consultant and check out the social media presence of the unit (#SoMe) as a proxy of their willingness to engage with social technology and communication

- Meet your colleagues: Spend time with future colleagues in the unit independent of the interview. Take some time to chat to nursing and clerical staff as well as other trainees. More information can be acquired about a unit over a cup of coffee with future colleagues than any other approach

In this time of flux within health service systems, trust, collegiality and communication as key. Things that sound apt are not always what they seem. The quotation attributed above to Darwin, is often one that is misquoted, and although seems appropriate, there is no evidence that he ever made that statement. In the same way, trainees can no longer be seen to be but from the same cloth. Their own lives and careers are unpredictable and multi-faceted, and the answers and applications relied on at interview do not guarantee a good correlation coefficient when plotted on a graph belonging to a particular unit i.e. not a “good fit”. Perhaps it is time to trust our own instincts when appointing a trainee to a particular unit by taking the time to meet candidates and assessing – in addition to applications and CVs – how they might slot into a department – so that when it comes to tackling overcrowding, waiting lists, theatre slots, emergencies, call, research, audit, management and teaching, at least they can be met with the strongest team possible.

“…it’s better in fact to be guilty of manslaughter than of fraud about what is fair and just…” (Plato, The Republic and Other Works)

Fardod O’Kelly is a Specialist Registrar in Urology at AMNCH, Tallaght, Dublin 24, Ireland. Twitter @FardodOKelly