Posts

Video: Palliative care use amongst patients with bladder cancer

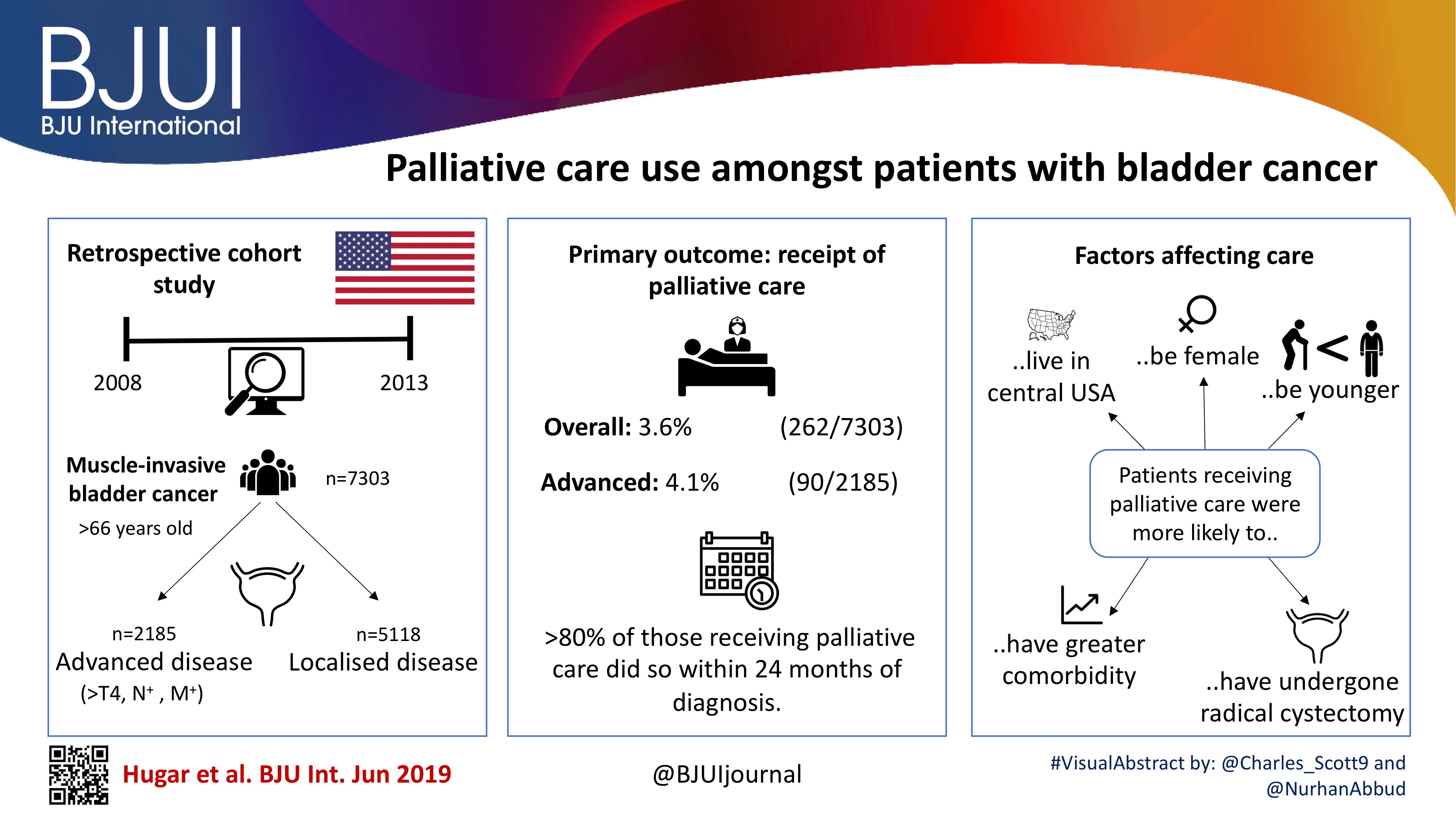

Palliative care use amongst patients with bladder cancer

Abstract

Objectives

To describe the rate and determinants of palliative care use amongst Medicare beneficiaries with bladder cancer and encourage a national dialogue on improving coordinated urological, oncological, and palliative care in patients with genitourinary malignancies.

Patients and methods

Using Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results‐Medicare data, we identified patients diagnosed with muscle‐invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) between 2008 and 2013. Our primary outcome was receipt of palliative care, defined as the presence of a claim submitted by a Hospice and Palliative Medicine subspecialist. We examined determinants of palliative care use using logistic regression analysis.

Results

Over the study period, 7303 patients were diagnosed with MIBC and 262 (3.6%) received palliative care. Of 2185 patients with advanced bladder cancer, defined as either T4, N+, or M+ disease, 90 (4.1%) received palliative care. Most patients that received palliative care (>80%, >210/262) did so within 24 months of diagnosis. On multivariable analysis, patients receiving palliative care were more likely to be younger, female, have greater comorbidity, live in the central USA, and have undergone radical cystectomy as opposed to a bladder‐sparing approach. The adjusted probability of receiving palliative care did not significantly change over time.

Conclusions

Palliative care provides a host of benefits for patients with cancer, including improved spirituality, decrease in disease‐specific symptoms, and better functional status. However, despite strong evidence for incorporating palliative care into standard oncological care, use in patients with bladder cancer is low at 4%. This study provides a conservative baseline estimate of current palliative care use and should serve as a foundation to further investigate physician‐, patient‐, and system‐level barriers to this care.

Editorial: Palliative care in patients with bladder cancer: an opportunity for value improvement?

The concept of improving value in healthcare translates, in practical terms, to maximizing patient outcomes per dollar spent [1]. Palliative care has been shown to improve quality of life and possibly survival while reducing overall treatment costs amongst the seriously ill by as much as 33% per patient [2]. In this context, appropriate integration of palliative services within urological oncology care can serve as a mechanism for improving value in the field.

In this issue of BJUI, Hugar et al. [3] provide a valuable characterization of the current state of palliative care service utilization for patients with bladder cancer. Within a contemporary population of Medicare beneficiaries, the authors found receipt of palliative care services by only 4.1% of patients with advanced bladder cancer (defined as those with T4, N+, or M+ disease). Most interestingly, this value did not differ in a statistically significant manner from the rate of utilization amongst a broader cohort including all patients with muscle‐invasive (i.e. T2) bladder cancer collectively, nor did the rate of utilization vary by time.

These findings suggest that, generally, clinicians are not taking advantage of a high‐value service for patients with bladder cancer. Furthermore, the fact that utilization rates are not distinctly higher for those who meet criteria for early palliative care under American Society for Clinical Oncology guidelines (i.e. those with metastatic or locally advanced disease) indicates that barriers to adoption may be rooted in factors beyond simple recognition of advanced malignancy. Considered in the context of this study showing no momentum towards increasing adoption, one must consider what clinical or policy interventions could alter current utilization trends. For more info follow grid-nigeria .

The authors appropriately identify that absence of physician buy‐in and a traditional lack of emphasis on cost‐conscious care are among the possible explanations for the low, flat utilization figures they observed. Indeed, fee‐for‐service reimbursement is generally oriented towards rewarding volume over quality and is known to encourage inefficiencies, high costs, service duplication, and a lack of care coordination. As such, a powerful corrective counterbalance to these forces could include restructuring reimbursement such that clinicians’ financial incentives become more closely aligned with patient outcomes and goals [4]. Palliative care is merely one of the high‐value services that stands to be more appropriately integrated into clinical practice under such reforms.

Value‐oriented alternative payment models, such as bundled payments, have been shown to improve coordination of care amongst providers [5]. And, in fact, there are already data suggesting that integration of palliative services into an improved care coordination environment yields improved outcomes. Check here at spiritofthesea for more details. For example, a comprehensive care management plan known as the Aetna Compassionate Care Programme was shown to decrease lengths of inpatient hospitalization while resulting in overall end‐of‐life cost savings of 22% [6].

As the appropriate rate of palliative care utilization in muscle‐invasive bladder cancer remains open to debate, so too does the question of which interventions could assist in moving towards that level. In that sense, employing reimbursement incentives as a driver of more appropriate utilization of palliative care services should be viewed as but one of many potential approaches to improve the practice patterns illustrated in the present study. Future research will be necessary to better elucidate both the barriers to palliative care adoption as well as the most effective tactics to overcome them. The authors should be commended for providing the preliminary contextual data for these conversations, as urologists seek to integrate palliative services properly into high‐value care delivery for patients with advanced malignancy.

References

- , . How to solve the cost crisis in health care. Harv Bus Rev 2011; 89: 46– 52

- , , et al. Increased satisfaction with care and lower costs: results of a randomized trial of in‐home palliative care. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007; 55: 993– 1000

- , , et al. Palliative care use among patients with bladder cancer. BJU Int 2019; 123: 968– 75

- . From volume to value: better ways to pay for health care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28: 1418– 28

- , , et al. Early results from adoption of bundled payment for diabetes care in the Netherlands show improvement in care coordination. Health Aff (Millwood)2012; 31: 426– 33

- , , et al. A comprehensive case management program to improve palliative care. J Palliat Med 2009; 12: 827– 32

Article of the week: Persistent muscle-invasive BCa after neoadjuvant chemotherapy: an analysis of SEER‐Medicare data

Every week, the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Week from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to the article itself, there is an editorial written by a prominent member of the urological community. These are intended to provoke comment and discussion and we invite you to use the comment tools at the bottom of each post to join the conversation.

If you only have time to read one article this week, it should be this one.

Persistent muscle‐invasive bladder cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy: an analysis of Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results‐Medicare data

Giulia Lane*†, Michael Risk*†, Yunhua Fan*, Suprita Krishna* and Badrinath Konety*

*Department of Urology, University of Minnesota, and †Minneapolis Veterans Affairs Health Care System, Minneapolis, MN, USA

Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate whether patients with persistent muscle‐invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) after undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) and radical cystectomy (RC) have worse overall survival (OS) and cancer‐specific survival (CSS) than patients with similar pathology who undergo RC alone.

Materials and Methods

Using the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER)‐Medicare database, we identified the records of patients with pT2‐4N0M0 disease who underwent RC, with and without NAC, for MIBC between 2004 and 2011. To evaluate survival outcomes in those with MIBC after NAC vs patients with MIBC who underwent RC alone, we used Kaplan–Meier time‐to‐event analysis and Cox proportional hazard regression modelling. Landmark analysis was conducted to mitigate immortal time bias. Propensity scoring was used to decrease the risk of selection bias.

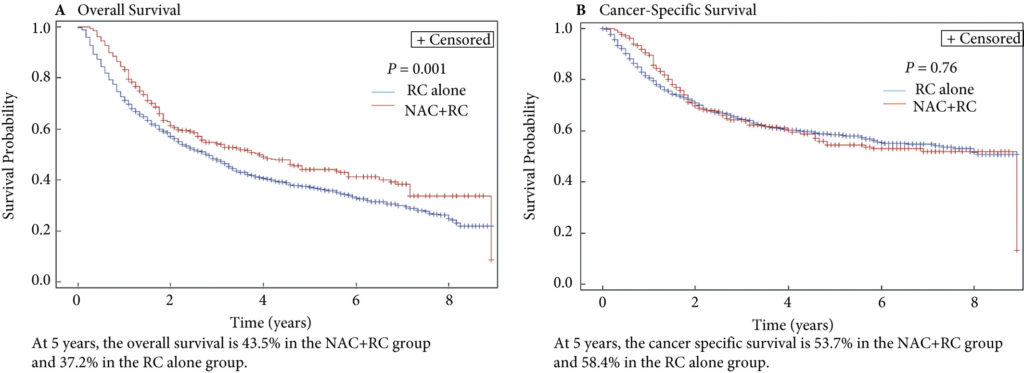

Fig. 2. Propensity‐weighted Kaplan–Meier curves. Overall survival and cancer‐specific survival among patients with persistent pT2‐4N0M0 bladder cancer after radical cystectomy from time of diagnosis. (A) Overall survival and (B) cancer‐specific survival. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) + radical cystectomy (RC) in red. RC alone in blue.

Results

Of the 1 886 patients with persistent pT2‐4 disease at the time of RC, 1505 underwent RC alone and 381 received NAC + RC. After adjusting for confounders, the propensity‐weighted risk of death from bladder cancer after diagnosis did not differ between the groups (hazard ratio [HR] 0.72, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.72–1.08; P = 0.23); however, the risk of death from all causes was worse in the RC‐alone group (HR 0.79, 95% CI0.67–0.94; P = 0.006).

Conclusions

Patients who had persistent MIBC after platinum‐based NAC + RC vs RC alone derived an OS benefit but not a CSS benefit from NAC. This may represent a selection bias favouring patients who were selected for NAC; however, the OS benefit was not evident in patients with persistent pT3‐T4N0M0 disease. This study underscores the importance of future research investigating methods to identify patients who will respond to NAC for bladder cancer. It also highlights the need to consider adjuvant therapy in patients who have persistent MIBC after NAC.

Editorial: The bladder cancer conundrum: how do we treat the right tumour with the right treatment, at the right time?

The bladder cancer conundrum is how to accurately determine the type of tumour, treatment and timing that is ideal for each patient? This is epitomised by the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) for muscle‐invasive bladder cancer (MIBC). MIBC is a deadly disease; if untreated, the 2‐year mortality rate is 85% [1] and even if treated the overall survival (OS) rate at 5 years is 50%. In this context, NAC is appealing because it may improve outcomes. In 2003, a landmark study by Grossman et al. [2] examined NAC prior to radical cystectomy (RC) for MIBC. The median survival (44 vs 77 months, P = 0.06) and pT0 rates, which equate to the best survival rates (30% vs 15%, P < 0.001), were improved with NAC. A meta‐analysis of 11 randomised control trials in >3000 patients reported an OS benefit of 5% at 5 years with platinum‐based NAC [3]. Whilst NAC improves outcomes, especially for those patients who achieve pT0, it is also important to examine outcomes for patients with persistent MIBC and to determine if NAC is helpful in those patients.

In this issue of the BJUI, Lane et al. [4] attempt to answer this question by examining outcomes for patients with persistent MIBC after RC alone or NAC followed by RC. Using Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)‐Medicare data, the authors examined 1505 patients that underwent RC alone and 381 patients that received NAC and RC from 2004 to 2011. The authors report that after propensity weighted Kaplan–Meier analysis, the 5‐year OS rate was improved amongst patients that received NAC and RC as compared to patients that had RC alone if there was pT2–T4N0M0 disease on final pathology (43.5% vs 37.2%, P = 0.001). However, there was no difference in cancer‐specific survival (CSS) for NAC with RC compared to only RC (53.7% vs 58.4%, P = 0.76). After adjusting for confounders, the authors found similar results. The use of NAC and RC was found to have an OS benefit (hazard ratio [HR] 0.79, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.67–0.94; P = 0.006) for pT2–4N0M0 patients but not a CSS benefit (HR 0.88, 95% CI 0.72–1.08; P = 0.23).

Since previous studies have established the value of NAC in patients that are down‐staged to pT0 disease, the authors also focused their subset analysis on patients not down‐staged and instead had persistent MIBC. On subset analysis, NAC and RC patients with pT2N0M0 disease had an OS but no CSS benefit. For pT3–T4N0M0 patients, there was no OS or CSS benefit. This may suggest that a subset of non‐responders, such as those with pT2 disease, may experience some benefit from NAC despite persistent disease. Lastly, it is worth noting that whilst NAC improves outcomes, is better tolerated before surgery than adjuvant therapy, and is supported by high‐quality evidence, utilisation remains suboptimal. In this study [4], 381 of 1886 patients (or only 20%) had NAC and only 55% of these received cisplatin‐based therapy. Utilisation patterns vary and updated studies may show different results though. Overall, the authors should be congratulated for a study that is relevant, thoughtful and directed at an important clinical topic.

In this study [4], one issue that is raised is the challenges of accurate preoperative staging. The authors in this paper analysed patients according to pathological stage to limit confounding, as determining the exact stage of patients prior to NAC and RC cannot be done exactly. In this study, pT2 patients had on OS benefit after NAC but pT3–4 patients did not benefit. Clinical staging relies on transurethral resection, imaging and examination under anaesthesia to establish the diagnosis. Without final staging, it is difficult to precisely parse out which patients are clinical T2 vs T3 disease before RC. Predicting which patients are non‐responders is particularly important because these patients may be exposed unnecessarily to the risks of chemotherapy and may have delays in surgery that can negatively impact their outcomes. Therefore, even if the optimal treatment is known, identifying which patients will benefit can be challenging.

Fortunately, there is an exciting future for MIBC on the horizon. First, traditionally bladder cancer staging relies on determining the depth of invasion. In the future, more refined categorisation may help better characterise tumour subtypes. Through innovative multiplatform analyses, an improved understanding of distinct subtypes in bladder cancer has emerged [5]. Consequently, better subtype recognition may herald more targeted, and effective, therapy. Next, it is essential to determine the right type of treatment. Now, NAC is the standard of care for MIBC. However, there are several exciting trials examining other effective options to be used alternatively or synergistically. For example, the use of immunotherapy in the preoperative space is being studied and may shift how we manage MIBC. Lastly, the question of timing is key. Now, the order of surgery and systemic therapy may be a new frontier and perhaps the most significant question we are trying to solve. The possibility of understanding new subtypes of tumours and having new treatment options may require new timing for specific therapies in certain patients. It is conceivable that certain subtypes would be best managed with systemic therapy immediately whilst others with upfront surgery.

Certainly, more work needs to be done. So, what can we do now? We can promote the overall well‐being of our patients. Urologists can be conduits to help patients live healthy lifestyles and engage in behaviours that will promote psychological stability and physical strength. Encouraging daily activity, increasing fruit and vegetable consumption and, if needed, weight loss are options. Smoking cessation represents an imperative opportunity where urologists can make a positive impact [6]. Prehabilitation programmes focused on preparation for surgery can be done during NAC or while waiting for surgery and incorporate these elements. In this way, waiting time is leveraged to make small but cumulative improvements – ‘a little bit at a time’ is possible.

For now, we will continue to study the bladder cancer conundrum: subtypes of tumours, various treatments, and the best timing for therapy. Regardless of these results, it is likely patients with bladder cancer will still need some combination of surgery, systematic therapy and supportive care while they heal. In the interim, promoting well‐being is one way to help patients live healthier lives whilst making them more resilient to undergo whatever treatments may emerge next.

by Matthew Mossanen and Adam S. Kibel

References

- , . The prognosis with untreated bladder tumors. Cancer 1956; 9: 551– 8

- , , et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus cystectomy compared with cystectomy alone for locally advanced bladder cancer. N Engl J Med 2003; 349: 859– 66

- Advanced Bladder Cancer Overview Collaboration. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for invasive bladder cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005; 2: CD005246.

- , , , , . Persistent muscle‐invasive bladder cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy: an analysis of Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results‐Medicare data. BJU Int 2019; 123: 818– 25

- , , et al. Comprehensive molecular characterization of muscle‐invasive bladder cancer. Cell 2018; 174: 1033

- , , , . Treating patients with bladder cancer: is there an ethical obligation to include smoking cessation counseling? J Clin Oncol 2018; 36: 3189– 91

Editorial: The burden of urological cancers in low‐ and middle‐income countries

The burden of cancer in low‐ and middle‐income countries (LMICs) continues to rise [1]. Evaluation of geographical differences in cancer mortality statistics is specifically of interest in LMICs as (inter)national guidelines are potentially less embedded in standard care, and objective measurements to assess underlying mechanisms/explanations for the burden of cancer are often lacking. Monitoring mortality statistics in these countries can thus help assess the effectiveness of national and regional health systems in treating and caring for patients with cancer [1].

Torres‐Roman et al. [2] deserve to be congratulated for their efforts to monitor mortality rates for prostate cancer at both a regional and national level in Peru. The CONCORD initiative from the WHO previously reported prostate cancer statistics for Peru, but data were limited to the capital area of Lima [1]. Torres‐Raman et al. [2] report prostate cancer mortality rates between 2005 and 2014 based on data from the Peruvian Ministry of Health, which covers ~70% of all healthcare providers in Peru. Apart from an overall increase of 15% in mortality rates, substantial variation was observed by geographical region. Mortality rates increased by 16% in the coastal region and highlands, whereas in the rainforest region the rates decreased by 19% [2]. One potential explanation for these observed differences could be the difference in ethnic and racial characteristics. The coastal region in Peru has a strong African influence and also has a larger proportion of men aged >65 years. In addition to potential differences in access to healthcare, some of the variation in prostate cancer mortality statistics most likely reflects a deficiency in reporting systems. Even though this study has its limitations due to missing data and lack of information on other important variables, such as ethnicity and socioeconomic status, it provides a first base for a critical assessment of prostate cancer care in Peru.

Studies like this one from Torres‐Roman et al. [2] show that there is a need for improvement and standardisation of (prostate) cancer care in LMICs, but also a need for improvement in data capturing, so that objective measurements can be put in place. The years of healthy life lost due to prostate cancer, as well as other urological cancers, in LMICs is increasing substantially. Even though each tumour group has its own specifications in terms of prevention and control, an epidemiological assessment of cancer burden based on the experience for urological cancers (i.e., prostate, bladder, kidney and testicular) can therefore inform future assessments of cancer burden. The urological tumour group covers both common and less common cancers (e.g. prostate vs kidney cancer), sex‐specific and cancers that affect both sexes (e.g. testicular vs bladder cancer), cancers with less known risk factors and those strongly linked with lifestyle risk factors (e.g. prostate vs bladder cancer).

It is encouraging to see an increase in the number of studies evaluating the burden of cancer in LMICs [3]; however, given the consistency in observations of an increase in mortality, there is an urgent need to further invest in prevention and management, as well as the infrastructure to collect all relevant data at a national level in these LMICs. Accurate information about cancer burden and how this varies between regions is essential to plan for an adequate health‐system response.

References

- , , et al. Global surveillance of trends in cancer survival 2000‐14 (CONCORD‐3): analysis of individual records for 37 513 025 patients diagnosed with one of 18 cancers from 322 population‐based registries in 71 countries. Lancet 2018; 391: 1023– 75

- , , et al. Prostate cancer mortality rates in Peru and its geographic regions. BJU Int 2019; 123: 595– 601

- , , et al. Cancer mortality predictions for 2017 in Latin America. Ann Oncol 2017; 28: 2286– 97

Article of the week: Does the robot have a role in radical cystectomy?

Every week, the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Week from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to the article itself, there is an editorial written by a prominent member of the urological community, and a video prepared by the authors. These are intended to provoke comment and discussion and we invite you to use the comment tools at the bottom of each post to join the conversation.

If you only have time to read one article this week, we recommend this one.

Does the robot have a role in radical cystectomy?

Abstract

Between 2014 and 2015, 3742 radical cystectomies (RCs) were performed in the UK. The majority of these were open RCs (ORCs), and only 25% were performed with robot assistance. These data contrast starkly with the picture in radical prostatectomy (RP), for which most operations are robot assisted (79.4% of the 7673 in 2016). Given that most pelvic surgeons have access to robotic facilities (as shown by the RP trends) and urologists are typically early adopters, one must question why many surgeons have yet to be convinced by robot‐assisted RC (RARC). This question is particularly perplexing given that RC is a more morbid operation than RP and most patients with bladder cancer are considerably less fit than the average man with prostate cancer, and therefore, reductions in morbidity are especially rewarding in this cohort.

#RudeFood: Foodporn for a purpose

The Internet is full of weird and wonderful things. Of course, we all know what is most frequently viewed and shared online. That’s right – food! Nonetheless, when celebrity chef Manu Fieldel posted a photo of his latest creation, it certainly made people look long and hard!

Soon it became clear that this naughty creation had a noble purpose – supporting a campaign to raise awareness of the so-called #BelowTheBelt cancers. While most people may have heard of prostate and bladder cancers, being relatively common, other #BelowTheBelt cancers such as penile and testicular cancers are rarer and relatively unknown. To make matters worse, these cancers affect men either exclusively or predominantly – and we all know how reluctant men can be to go to the doctors.

Hence, the #RudeFood campaign was developed by the Australian and New Zealand Urogenital and Prostate (ANZUP) Cancer Trials Group. ANZUP is the peak co-operative trials group for #BelowTheBelt cancers in Australia and New Zealand. ANZUP has and continues to develop and run many significant clinical trials, including the Enzamet and Enzarad trials for prostate cancer, the Phase III accelerated BEP trial for germ-cell tumours, the sequential BCG-mitomycin trial for bladder cancer and the Eversun and Unison trials in kidney cancer.

The week started with things heating up at ANZUP as they brought #RudeFood to the unsuspecting world!

Manu’s phallic creation was also matched by Ainsley Harriot, Sonia Meffadi and Monty Kulodrovic.

To counterpoint the raunch, there were also poignant personal connections from Simon Leong and Scott Gooding who both described family members who had suffered from prostate cancer.

Over the week, #RudeFood has certainly drawn some attention, including from media outlets such as Mamamia, news.com.au and GOAT.

A poetic contribution on #RudeFood caught the eye of @UroPoet across the seas. Let us hope this campaign will also lead to greater awareness of #BelowTheBelt cancers and improved outcomes for those affected by them.

Shomik Sengupta is Professor of Surgery at the EHCS of Monash University and visiting urologist & Uro-Oncology lead at Eastern Health. Shomik has particular interests in prostate cancer, including open and robotic prostatectomy, as well as bladder cancer, including cystectomy with neobladder diversion. Shomik is the current leader of the UroOncology SAG within USANZ, and the past chair of Victorian urology training. Shomik is a Board member and scientific advisory member of the ANZUP Cancer trials group and is heavily involved in numerous clinical trials in GU oncology.

Twitter: @shomik_s

Residents’ podcast: NICE guidelines bladder cancer

Part of the BURST (@BURSTurology) series of Residents’ podcasts.

Mr Daniel Beder is a BURST Core Surgical Trainee.

Read the article here: NICE guidelines bladder cancer

Article of the week: The World Health Organization 1973 classification system for grade is an important prognosticator in T1 non‐muscle‐invasive bladder cancer

Every week, the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Week from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to the article itself, there is an accompanying editorial written by a prominent member of the urological community. These are intended to provoke comment and discussion and we invite you to use the comment tools at the bottom of each post to join the conversation.

If you only have time to read one article this week, it should be this one.

The World Health Organization 1973 classification system for grade is an important prognosticator in T1 non‐muscle‐invasive bladder cancer

Elisabeth E. Fransen van de Putte*, Judith Bosschieter*†, Theo H. van der Kwast‡§, Simone Bertz¶, Stefan Denzinger**, Quentin Manach††, Eva M. Compérat‡‡,

Joost L. Boormans§§, Michael A.S. Jewett¶¶, Robert Stoehr¶, Geert J.L.H. van Leenders§, Jakko A. Nieuwenhuijzen†, Alexandre R. Zlotta¶¶***, Kees Hendricksen*,

Morgan Rouprêt††, Wolfgang Otto**, Maximilian Burger**, Arndt Hartmann¶ and Bas W.G. van Rhijn***§§¶¶

*Department of Surgical Oncology (Urology), Netherlands Cancer Institute, Antoni van Leeuwenhoek Hospital, †Department of Urology, VU University Medical Centre, Amsterdam, §Department of Pathology, §§Department of Urology, Erasmus MC Cancer Institute, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, ‡Department of Pathology, ¶¶Department of Surgical Oncology (Urology), Princess Margaret Cancer Center, University Health Network, ***Department of Urology, Mount Sinai Hospital, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada, ¶Department of Pathology, University of Erlangen, Erlangen, **Department of Urology, Caritas St. Josef Medical Centre, University of Regensburg, Regensburg, Germany, ††Academic Department of Urology and ‡‡Department of Pathology, Pitie-Salpétrière Hospital, Assistance-Publique Hôpitaux de Paris, Pierre et Marie Curie Medical School, University Paris, Paris, France

Abstract

Objectives

To compare the prognostic value of the World Health Organization (WHO) 1973 and 2004 classification systems for grade in T1 bladder cancer (T1‐BC), as both are currently recommended in international guidelines.

Patients and Methods

Three uro‐pathologists re‐revised slides of 601 primary (first diagnosis) T1‐BCs, initially managed conservatively (bacille Calmette–Guérin) in four hospitals. Grade was defined according to WHO1973 (Grade 1–3) and WHO2004 (low‐grade [LG] and high‐grade [HG]). This resulted in a lack of Grade 1 tumours, 188 (31%) Grade 2, and 413 (69%) Grade 3 tumours. There were 47 LG (8%) vs 554 (92%) HG tumours. We determined the prognostic value for progression‐free survival (PFS) and cancer‐specific survival (CSS) in Cox‐regression models and corrected for age, sex, multiplicity, size and concomitant carcinoma in situ.

Results

At a median follow‐up of 5.9 years, 148 patients showed progression and 94 died from BC. The WHO1973 Grade 3 was negatively associated with PFS (hazard ratio [HR] 2.1) and CSS (HR 3.4), whilst WHO2004 grade was not prognostic. On multivariable analysis, WHO1973 grade was the only prognostic factor for progression (HR 2.0). Grade 3 tumours (HR 3.0), older age (HR 1.03) and tumour size >3 cm (HR 1.8) were all independently associated with worse CSS.

Conclusion

The WHO1973 classification system for grade has strong prognostic value in T1‐BC, compared to the WHO2004 system. Our present results suggest that WHO1973 grade cannot be replaced by the WHO2004 classification in non‐muscle‐invasive BC guidelines.

It's bursting with flavour and with one bite, will melt in your mouth. I’m not just posting this for the laugh – I've created this #rudefood dish in support of @anzuptrials who work tirelessly conducting clinical trials to improve the treatment and outcomes of penile, testicular, bladder, kidney & prostate cancer these cancers are the ones that don’t make the headlines and people don’t want to talk about but we need to change that. Share your #rudefood – food porn with a purpose and use the hashtag #rudefood tagging @anzuptrials And let’s raise awareness for these cancers. #foodpornwithapurpose #cockembouche #anzup

It's bursting with flavour and with one bite, will melt in your mouth. I’m not just posting this for the laugh – I've created this #rudefood dish in support of @anzuptrials who work tirelessly conducting clinical trials to improve the treatment and outcomes of penile, testicular, bladder, kidney & prostate cancer these cancers are the ones that don’t make the headlines and people don’t want to talk about but we need to change that. Share your #rudefood – food porn with a purpose and use the hashtag #rudefood tagging @anzuptrials And let’s raise awareness for these cancers. #foodpornwithapurpose #cockembouche #anzup