mCRPC, metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer; PD-L1, programmed death ligand 1. The total number of current trials of immune checkpoint inhibitors is 46 for lung, breast, ovarian, rectal, prostate, pancreatic, bladder, renal cancers and melanoma.

Posts

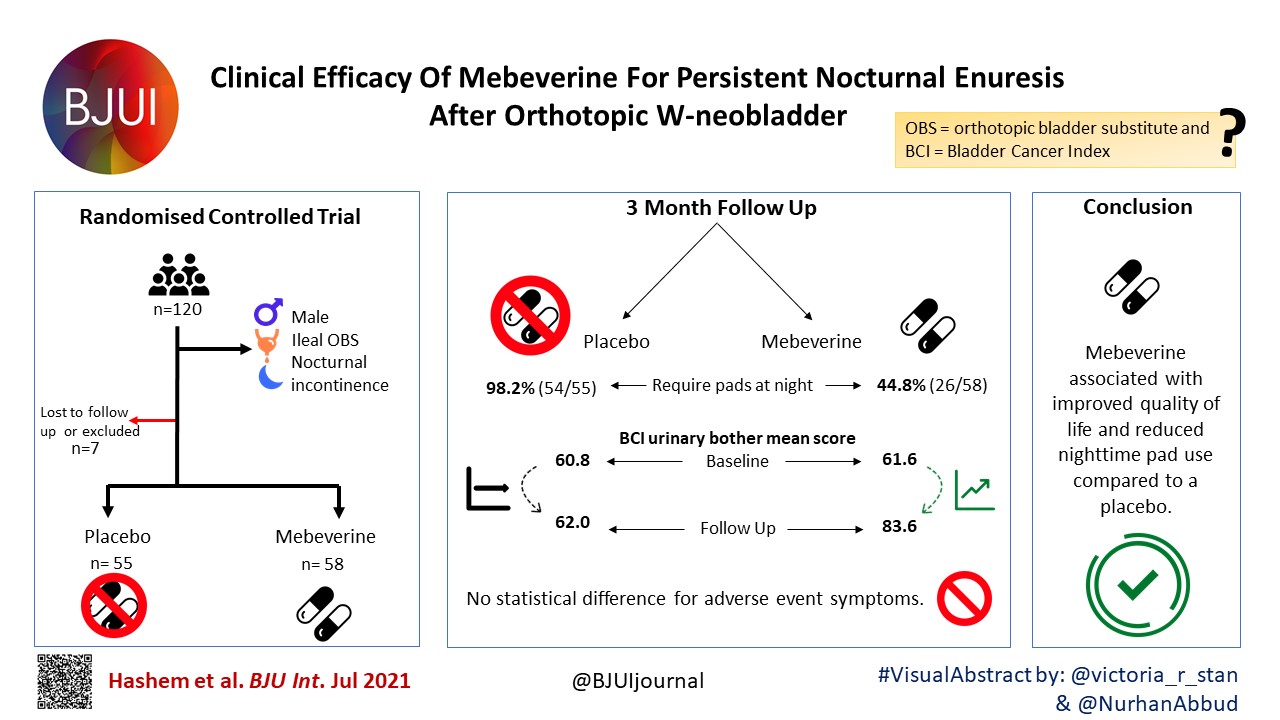

Article of the Week: β3‐adrenoceptor agonists inhibit carbachol‐evoked Ca2+ oscillations in murine detrusor myocytes

Every Week, the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Week from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to the article itself, there is an accompanying editorial written by a prominent member of the urological community. This blog is intended to provoke comment and discussion and we invite you to use the comment tools at the bottom of each post to join the conversation.

Finally, the third post under the Article of the Week heading on the homepage will consist of additional material or media. This week we feature a video discussing the paper.

If you only have time to read one article this week, it should be this one.

β3‐adrenoceptor agonists inhibit carbachol‐evoked Ca2+ oscillations in murine detrusor myocytes

Abstract

Objective

To test if carbachol (CCh)‐evoked Ca2+ oscillations in freshly isolated murine detrusor myocytes are affected by β3‐adrenoceptor (β‐AR) modulators.

Materials and Methods

Isometric tension recordings were made from strips of murine detrusor, and intracellular Ca2+ measurements were made from isolated detrusor myocytes using confocal microscopy. Transcriptional expression of β‐AR sub‐types in detrusor strips and isolated detrusor myocytes was assessed using reverse transcriptase‐polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR) and real‐time quantitative PCR (qPCR). Immunocytochemistry experiments, using a β3‐AR selective antibody, were performed to confirm that β3‐ARs were present on detrusor myocytes.

Results

The RT‐PCR and qPCR experiments showed that β1‐, β2‐ and β3‐AR were expressed in murine detrusor, but that β3‐ARs were the most abundant sub‐type. The selective β3‐AR agonist BRL37344 reduced the amplitude of CCh‐induced contractions of detrusor smooth muscle. These responses were unaffected by addition of the BK channel blocker iberiotoxin. BRL37344 also reduced the amplitude of CCh‐induced Ca2+ oscillations in freshly isolated murine detrusor myocytes. This effect was mimicked by CL316,243, another β3‐AR agonist, and inhibited by the β3‐AR antagonist L748,337, but not by propranolol, an antagonist of β1‐ and β2‐ARs. BRL37344 did not affect caffeine‐evoked Ca2+ transients or L‐type Ca2+ current in isolated detrusor myocytes.

Conclusion

Inhibition of cholinergic‐mediated contractions of the detrusor by β3‐AR agonists was associated with a reduction in Ca2+ oscillations in detrusor myocytes.

Editorial: β3‐adrenoceptor agonists inhibit calcium oscillations in bladder detrusor

The β3‐adrenoceptor (β3‐AR) agonist mirabegron has now been used clinically for the treatment for overactive bladder (OAB) for 5 years, but it is still not clear either exactly where the β3‐ARs are located within the bladder wall or entirely how they work. β3‐AR agonists can reduce detrusor contractions after cholinergic stimulation, but the concentrations of mirabegron required for this effect suggest that this is unlikely to be the main therapeutic route, which may instead involve an indirect pathway or a combination of pathways.

In this issue of BJUI, Griffin et al. 1 show that β3‐AR agonists can reduce the rise in calcium and calcium waves observed after muscarinic receptor activation with carbachol in murine detrusor smooth muscle. They convincingly demonstrate that this effect is mediated by β3‐AR rather than by β1‐AR or β2‐AR and is not mediated by an effect on L‐type calcium channels or depletion of calcium stores; however, although they use BRL37344 and CL316,243, which have a higher potency in rodents than mirabegron, the concentrations of these agents needed are in the micromolar range, significantly higher than the values of ~100 nM measured in plasma following therapeutic dosing with mirabegron 2. It will be interesting to see when these experiments are repeated with, these effects on calcium are also seen in the therapeutic dosing range.

Currently, the only effects of mirabegron reported in the therapeutic dosing range are a reduction in detrusor contractions when elicited by field stimulation and a reduction in acetylcholine release from detrusor strips 3, 4. The similarly of the concentrations required for these two effects have led to the suggestion that the reduction in contractions may be mediated by the reduction in acetylcholine release; however, there is still disagreement as to whether β3‐ARs are located in the cholinergic nerve terminals or not, as different groups have obtained different patterns of β3‐adrenoreceptor staining, even when using the same antibodies 4–6. It is therefore still unclear if this involves a direct inhibition of acetylcholine release or not, although a predominantly neural source of acetylcholine is indicated by sensitivity to the sodium channel blocker, tetrodotoxin 3.

There is evidence that the reduction may be at least partially mediated via adenosine, such that increased adenosine formed post‐junctionally from breakdown of cAMP following β3‐AR stimulation, acts as a retrograde transmitter to inhibit acetylcholine release by acting at pre‐junctional A1 receptors 4. In support of this, Silva et al. 4 showed that A1 antagonists can reverse the increase in voiding seen with isoprenaline in an anaesthetized rat cystoscopy model.

The reduction in calcium rise reported by Griffin et al. 1 also suggests a post‐junctional site of action and the likely possibility that multiple pathways are activated following the binding of the β3‐AR agonists to post‐junctional receptors. A multiple pronged mechanism may be one of the reasons why mirabegron is successful at reducing the symptoms of OAB whilst sparing normal voiding.

The potency of β3‐AR agonists shows differences depending on the method of stimulation of the muscle, with higher potency seen for inhibition of contraction induced by field stimulation than carbachol stimulation, for example 1, 3, 4. This may reflect differences in the combinations of pathways and receptors activated, with carbachol stimulating only the muscarinic receptors themselves, but field stimulation activating more widely. It would therefore be interesting to see whether the potency of mirabegron to affect calcium release in human tissue is higher when field stimulation is used rather than carbachol, and hence help to evaluate if this pathway is involved in the mechanism of action of mirabegron in the clinic.

- 1 Griffin CS, Bradley E, Hollywood MA, McHale NG, Thornbury KD, Sergeant GP. B3‐adrenoceptor agonists inhibit carbachol‐evoked Ca2+ oscillations in murine detrussor myocytes. BJU Int 2018; 121: 959–70

- 2 Krauwinkel W, van Dijk J, Schaddelee M et al. Pharmacokinetic properties of mirabegron, a beta(3)‐adrenoceptor agonist: results from two phase I, randomized, multiple‐dose studies in healthy young and elderly men and women. Clin Ther 2012; 34: 2144–60

- 3 D’Agostino G, Condino AM, Calvi P. Involvement of beta(3)‐adrenoceptors in the inhibitory control of cholinergic activity in human bladder: direct evidence by H‐3‐acetylcholine release experiments in the isolated detrusor. Eur J Pharmacol 2015; 758: 115–22

- 4 Silva I, Costa AF, Moreira S et al. Inhibition of cholinergic neurotransmission by beta(3)‐adrenoceptors depends on adenosine release and A(1)‐receptor activation in human and rat urinary. Am J Physiol‐Renal Physiol 2017; 313: F388–403

- 5 Coelho A, Antunes‐Lopes T, Gillespie J, Cruz F. Beta‐3 adrenergic receptor is expressed in acetylcholine‐containing nerve fibers of the human urinary bladder: an immunohistochemical study. Neurourol Urodyn 2017; 36: 1972–80

- 6 Limberg BJ, Andersson KE, Kullmann FA, Burmer G, de Groat WC, Rosenbaum JS. beta‐Adrenergic receptor subtype expression in myocyte and non‐myocyte cells in human female bladder. Cell Tissue Res 2010; 342: 295–306

Video: β3‐adrenoceptor agonists inhibit carbachol‐evoked Ca2+ oscillations in murine detrusor myocytes

β3‐adrenoceptor agonists inhibit carbachol‐evoked Ca2+ oscillations in murine detrusor myocytes

Abstract

Objective

To test if carbachol (CCh)‐evoked Ca2+ oscillations in freshly isolated murine detrusor myocytes are affected by β3‐adrenoceptor (β‐AR) modulators.

Materials and Methods

Isometric tension recordings were made from strips of murine detrusor, and intracellular Ca2+ measurements were made from isolated detrusor myocytes using confocal microscopy. Transcriptional expression of β‐AR sub‐types in detrusor strips and isolated detrusor myocytes was assessed using reverse transcriptase‐polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR) and real‐time quantitative PCR (qPCR). Immunocytochemistry experiments, using a β3‐AR selective antibody, were performed to confirm that β3‐ARs were present on detrusor myocytes.

Results

The RT‐PCR and qPCR experiments showed that β1‐, β2‐ and β3‐AR were expressed in murine detrusor, but that β3‐ARs were the most abundant sub‐type. The selective β3‐AR agonist BRL37344 reduced the amplitude of CCh‐induced contractions of detrusor smooth muscle. These responses were unaffected by addition of the BK channel blocker iberiotoxin. BRL37344 also reduced the amplitude of CCh‐induced Ca2+ oscillations in freshly isolated murine detrusor myocytes. This effect was mimicked by CL316,243, another β3‐AR agonist, and inhibited by the β3‐AR antagonist L748,337, but not by propranolol, an antagonist of β1‐ and β2‐ARs. BRL37344 did not affect caffeine‐evoked Ca2+ transients or L‐type Ca2+ current in isolated detrusor myocytes.

Conclusion

Inhibition of cholinergic‐mediated contractions of the detrusor by β3‐AR agonists was associated with a reduction in Ca2+ oscillations in detrusor myocytes.

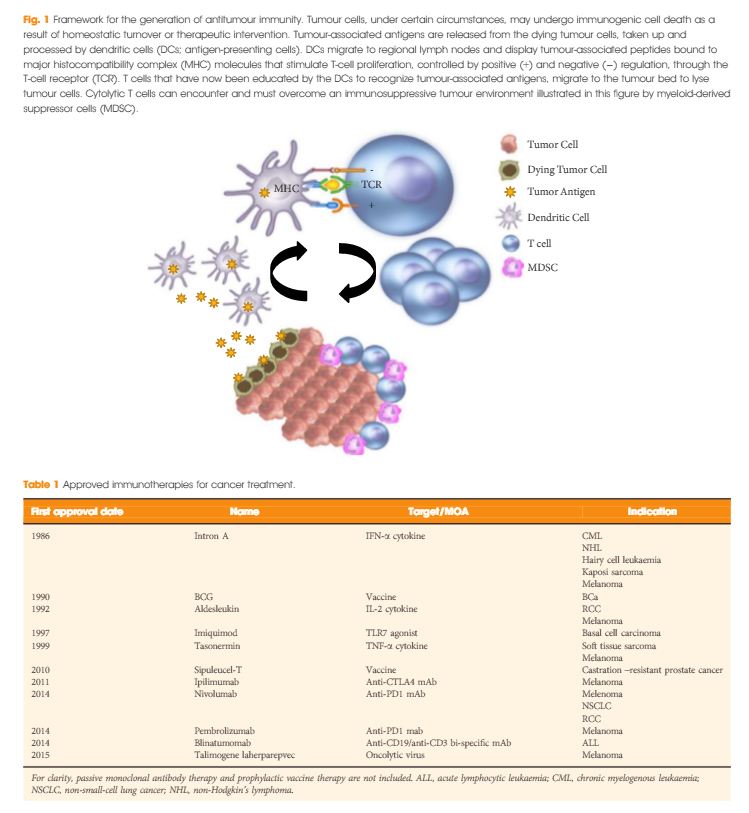

Article of the Month: Recent advances in immuno-oncology and its application to urological cancers

Every Month the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Month from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to the article itself, there is an accompanying comment written by a prominent member of the urological community. This blog is intended to provoke comment and discussion and we invite you to use the comment tools at the bottom of each post to join the conversation.

If you only have time to read one article this week, it should be this one.

Recent advances in immuno-oncology and its application to urological cancers

Abstract

Recent advances in immuno-oncology have the potential to transform the practice of medical oncology. Antibodies directed against negative regulators of T-cell function (checkpoint inhibitors), engineered cell therapies and innate immune stimulators, such as oncolytic viruses, are effective in a wide range of cancers. Immune‘based therapies have had a clinically meaningful impact on the treatment of advanced melanoma, and the lessons regarding use of single agents and combinations in melanoma may be applicable to the treatment of urological cancers. Checkpoint inhibitors, cytokine therapy and therapeutic vaccines are already showing promise in urothelial bladder cancer, renal cell carcinoma and prostate cancer. Critical areas of future immuno-oncology research include the prospective identification of patients who will respond to current immune-based cancer therapies and the identification of new therapeutic agents that promote immune priming in tumours, and increase the rate of durable clinical responses.

Comment: Immune checkpoint blockade – a treatment for urological cancers?

Introduction

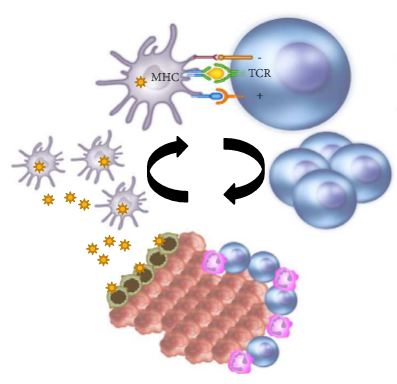

In the last few years there have been concerted attempts at using the power of the immune system as an effective treatment option for cancer. This has become possible as our understanding of the workings of the immune system has improved. Tumours form because of failure of the organism to destroy a rogue, mutated cell in an appropriate way. Once the tumour is formed it can further develop when the immune system fails to contain and control it and certain equilibrium is lost in favour of the tumour. This is referred to as the immune editing theory. At this point of failure of the immune system, tumour growth and progression become possible and tumours develop various mechanisms to evade the immune systems surveillance. Therefore, a mechanism to restore the lost equilibrium or to tip it in favour of the immune system would be a new modality in anti-cancer treatment. The initial approach was to use stimulators of the immune system systemically such as interleukin 2 and interferon γ i.v. in patients with metastatic cancers including melanoma and renal cancers [1]. A sustained response was shown in 22% of patients with metastatic kidney cancer, lasting for over a year. Although this treatment was not a resounding success, it did highlight an approach that could yield a durable tumour regression in a minority of cases. As our understanding of the immune system–tumour interaction further developed, new research focused on a specific mechanism in the immune system that seems to be exploited by tumours. This is an activation-inhibition mechanism, which controls the extent of adaptive immune response to invading organisms or to mutated cancer cells. In healthy individuals, this mechanism is a ‘safety’ feature allowing cessation of the immune response once it has performed its task. This is controlled by ‘receptor’ molecules at the T-cell surface and their corresponding ‘ligands’ at the surface of the cells interacting with the T-cell, which can be an antigen presenting cell or a tumour cell surface. This mechanism is called the immune checkpoint [2] (Fig. 1). Cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) and programmed death 1 (PD-1) are the most well-known checkpoints but there are up to 20 others (and counting) [2]. Their main role is to inhibit an immune response by blocking the activation of T-cells when those cells are presented with a foreign antigen or cancer proteins. This inhibition leads to immune ‘tolerance’ of the presence of cancer cells. So the policeman (T cell) is oblivious to the robbery in front of him. Thus an anti-tumour treatment strategy to disrupt the immune checkpoints seems to be a valid one (Table 1).

Figure 1. Blocking checkpoint inhibitors with antibodies is the new immunotherapy strategy to unlock T-cell activation and improve anti-tumour immune response. MHC, major histocompatibility complex; PD-L1, programmed death ligand 1; TCR, T-cell antigen receptor.

| Tumour | Phase | Treatment | N | Results | Trial.gov identifier |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| mCRPC | 1 | Dendritic cell therapy and ipilimumab | 20 | Recruiting | NCT02423928 |

| All advanced solid tumours | 1 | Various combinations of ipilimumab, nivolumab and pembrolizumab | 122 | Recruiting | NCT02467361 |

| RCC | 3 | Nivolumab vs everolimus | 822 | Recruiting | NCT01668784 |

| RCC | 3 | Atezolizumab (anti PD-L1) | 70 | Good safety profile with antitumour activity | NCT01375842 |

| mCRPC | 3 | Ipilimumab vs placebo | 799 | No improvement of survival in treatment group | NCT00861614 |

| Urothelial | 2 | Gemcitabine, cisplatin and ipilimumab combinations | 36 | Recruiting | NCT01524991 |

In recent years, a plethora of various inhibitors in the form of monoclonal antibodies to the checkpoint molecules were developed and to date three at least have been approved by the USA Food and Drug Administration (FDA) – ipilimumab (Yervoy), nivolumab (Opdivo), and pembrolizumab (Keytruda). They are anti-CTLA4 and anti-PD-1 antibodies. At least another eight checkpoint inhibitors are being developed. These agents have been shown to have survival benefit in some malignancies and limited benefit in others. However, the breakthrough seems to be happening in the treatment of metastatic malignant melanomas where immune checkpoint inhibitors treatment may become the standard of care. Patients with metastatic malignant melanoma who were treated with ipilimumab had a median survival of ~11 months; however, 22% of patients survived for ≥3 years with a plateau in the survival curve and in a subset of patients up to 10 years [3]. This success has not yet been replicated in prostate cancer [4]. In a more recent clinical trial involving patients with melanoma who progressed, nivolumab showed survival benefit of 72% at 1 year as compared with 42% with dacarbazine [5]. The latest approach is to combine anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1 in one treatment regime as they are expected to act synergistically to remove the inhibition to the immune response, and clinical results seem to show survival benefit for combined therapy [6]. Combination of different treatment methods may potentiate the ‘abscopal effect’, which is seen when local radiation therapy can cause regression of tumour distant to the radiation site. This seems to be mediated by the immune system and potentiated by checkpoint inhibitors. Until now checkpoint inhibitors were used in patients with end-stage metastatic cancer, but recently anti-CTLA-4 has been trialled in pre-radical cystectomy patients not as a neoadjuvant therapy but rather to monitor immune response and surgical safety [2]. It is likely that checkpoint inhibitors will have a place in cancer treatment including urological cancers. However, this new class of anti-cancer treatment comes with a price. The emerging risks and side-effect profile of checkpoint inhibitors are completely different from those seen with the conventional chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Those side-effects are related to the activation of the immune system. Although most are not uncommon, they can occasionally have devastating effect on the patients. These side-effects include autoimmune conditions like dermatitis, mild colitis, and occasionally hepatitis. A severe form of colitis resulting in perforation has been reported. Unfortunately, the rate of adverse effects seems to correlate with positive clinical response. A list of some of the side-effects is summarised in Table 2. Treatment is usually with steroids, and clinicians are starting to develop strategies to minimise those risks.

| Adverse effects | |

|---|---|

| Common | Rare |

| Diarrhoea | Severe colitis – colonic perforation |

| Pruritus/dermatitis | Adrenal insufficiency |

| Rash | Panhypopituitarism |

| Colitis | Hepatitis |

| Fatigue | Uveitis |

| Decreased appetite | Temporal arteritis |

The cost of checkpoint inhibitors remains relatively high and a full treatment course of ipilimumab costs >£18 000. One dose of pembrolizumab can cost >£3 500. However, the National Institute for Health and Care excellence (NICE) in the UK deemed this to be cost-effective and approved it for patients with metastatic melanoma that has progressed despite ipilimumab treatment.

Will the 21st century be the era for immunotherapy? It is still too early to tell. At present it remains rather expensive and beyond the means of many patients with cancer.

Article of the Month: IFES to manage non-neuropathic UAB in children

Every Month the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Month from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to the article itself, there is an accompanying editorial written by a prominent member of the urological community. This blog is intended to provoke comment and discussion and we invite you to use the comment tools at the bottom of each post to join the conversation.

Finally, the third post under the Article of the Week heading on the homepage will consist of additional material or media. This week we feature a video from Sanam Ladi Seyedian, discussing her paper.

If you only have time to read one article this week, it should be this one.

Transcutaneous interferential electrical stimulation for the management of non-neuropathic underactive bladder in children: a randomised clinical trial

Objectives

To assess the efficacy of transcutaneous interferential electrical stimulation (IFES) and urotherapy in the management of non-neuropathic underactive bladder (UAB) in children with voiding dysfunction.

Patients and Methods

In all, 36 children with UAB without neuropathic disease [15 boys, 21 girls; mean (sd) age 8.9 (2.6) years] were enrolled and then randomly allocated to two equal treatment groups comprising IFES and control groups. The control group underwent only standard urotherapy comprising diet, hydration, scheduled voiding, toilet training, and pelvic floor and abdominal muscles relaxation. Children in the IFES group likewise underwent standard urotherapy and also received IFES. Children in both groups underwent a 15-session treatment programme twice a week. A complete voiding and bowel habit diary was completed by parents before, after treatment, and 1 year later. Bladder ultrasound and uroflowmetry/electromyography were performed before, at the end of treatment course, and at the 1-year follow-up.

Results

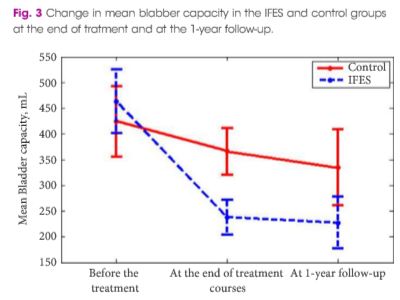

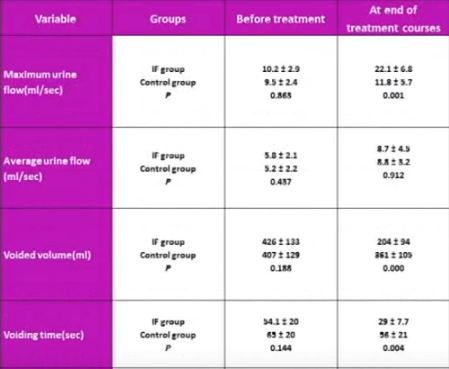

The mean (sd) number of voiding episodes before treatment was 2.6 (1) and 2.7 (0.76) times/day in the IFES and control groups, respectively, which significantly increased after IFES therapy in IFES group, compared with only standard urotherapy in the control group [6.3 (1.4) vs 4.7 (1.3) times/day, P < 0.002). The mean (sd) bladder capacity before treatment was 424 (123) and 463 (121) mL in the control and IFES groups, respectively, which decreased significantly at 1 year after treatment in the IFES group compared with the controls, at 227 (86) vs 344 (127) mL (P < 0.01). Maximum urine flow increased and voiding time decreased significantly in the IFES group compared with controls at the end of treatment sessions and 1 year later (P < 0.05). All the children had abnormal flow curves at the beginning of the study. The flow curve became normal in 14/18 (77%) of the children in the IFES group and six of 18 (33%) in the control group by the end of follow-up (P < 0.007). At the end of the treatment course, night-time wetting was improved in all children who had this symptom before the treatment in the IFES group (P < 0.01).

Conclusion

Combining IFES and urotherapy is a safe and effective therapy in the management of children with UAB.

Editorial: The vexing problem of UAB in children – a viable alternative

Underactive bladder, as defined by the International Children’s Continence Society (ICCS; impaired detrusor contractility that leads to low voiding frequency (<3 voids/day), hesitancy, incomplete bladder emptying, and high post-void residual urine volumes (PVRs) that may produce UTI and urinary incontinence) has been a vexing problem for many paediatric providers to manage.

Antimuscarinic and α-agonist drugs have not proven effective to warrant their recommendation, and urotherapy, which demystifies the condition and tries to teach children to void often, take the time to urinate, use correct posture, and promote dietary habits that seem to adjudicate fluid intake, resulting in appropriate urine production and regular bowel movements, have not fully solved the problems in all patients. More invasive therapies, i.e., percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation, intravesical electrical stimulation, and sacral neuromodulation provide some improvement in mollifying symptoms but long-term responses do not seem to be sustainable. Intermittent catheterisation, which immediately achieves bladder emptying on a timely schedule, is often a therapy that children and their parents prefer to avoid. All these management options with their varying responses have left patients resigned as their symptoms persist and their parents frustrated.

Kajbafzadeh et al. [1], in a study reported in this issue of the Journal, have clearly shown the value and potential promise of interferential electrical stimulation (IFES) for non-neuropathic underactive bladder in children. IFES changes bladder dynamics so that urinary frequency, bladder contractility, and PVRs improve to the extent that incontinence, both daytime and night-time, as well as UTIs, resolve. Although it is time consuming, as one would expect all therapies that reverse pathological processes might be, the promise that long-term responses remain salient is a testament to its worthiness. As a reference, Kajbafzadeh et al. [2] recently published similar responses in a randomised clinical trial of children with primary monosymptomatic enuresis, using standard urotherapy (as used in this current study [1]) with and without IFES, which revealed statistically significant improvement in enuretic episodes, both initially and after 1 year in those children treated with IFES. In a previous randomly allocated report of 30 children with myelomeningocele and detrusor overactivity, IFES was substantially effective in 20 vs 10 who were ‘sham controlled’ [3].

The authors [1] do indicate deficiencies in their study, the most glaring of which is the absence of a ‘sham’ group of children who should have ‘received’ IFES treatment without any actual ES. In clinical practice this is almost impossible to achieve. Long-term urodynamic data would also have been helpful in solidifying these responses when compared to pre-treatment investigations but again having families assent to a study that involves catheterising their child for this purpose is nearly impossible.

The authors did not comment on the improvement in bowel function these children may experience in the immediate period after treatment or in the long-term, but given the emphasis on better toileting it is presumed lower gastrointestinal function would have been helped as well. In addition, the authors [1] have left us wondering if these improved toileting habits changed the propensity towards UTIs over time. Nor have they expressed any improvement in behavioural issues as a result of this programme, or what effect, if any, has occurred regarding school performance and social interaction. It is now up to these pioneers, as well as future investigators, to lead the way to engage a child’s entire milieu and his family responses, to the acceptability of this treatment programme. Looking beyond just the immediacy of an IFES regimen and its effects on the urinary and gastrointestinal systems will surely tell us if this management schema truly has large scale merit for a wider cohort. That kind of communication would surely be an impetus for scientifically minded clinicians to delve into the ‘whys’ of its positive pathophysiological effects.

I commend the authors for their exceptional work and desire to find an effective, minimally invasive treatment that has long-term sustainability. The gauntlet has been dropped, only to be picked up by others (or these same providers) to address and answer the additional concerns and questions posed by this editorial.

References

Video: IFES to manage non-neuropathic UAB in children

Transcutaneous interferential electrical stimulation for the management of non-neuropathic underactive bladder in children: a randomised clinical trial

Objectives

To assess the efficacy of transcutaneous interferential electrical stimulation (IFES) and urotherapy in the management of non-neuropathic underactive bladder (UAB) in children with voiding dysfunction.

Patients and Methods

In all, 36 children with UAB without neuropathic disease [15 boys, 21 girls; mean (sd) age 8.9 (2.6) years] were enrolled and then randomly allocated to two equal treatment groups comprising IFES and control groups. The control group underwent only standard urotherapy comprising diet, hydration, scheduled voiding, toilet training, and pelvic floor and abdominal muscles relaxation. Children in the IFES group likewise underwent standard urotherapy and also received IFES. Children in both groups underwent a 15-session treatment programme twice a week. A complete voiding and bowel habit diary was completed by parents before, after treatment, and 1 year later. Bladder ultrasound and uroflowmetry/electromyography were performed before, at the end of treatment course, and at the 1-year follow-up.

Results

The mean (sd) number of voiding episodes before treatment was 2.6 (1) and 2.7 (0.76) times/day in the IFES and control groups, respectively, which significantly increased after IFES therapy in IFES group, compared with only standard urotherapy in the control group [6.3 (1.4) vs 4.7 (1.3) times/day, P < 0.002). The mean (sd) bladder capacity before treatment was 424 (123) and 463 (121) mL in the control and IFES groups, respectively, which decreased significantly at 1 year after treatment in the IFES group compared with the controls, at 227 (86) vs 344 (127) mL (P < 0.01). Maximum urine flow increased and voiding time decreased significantly in the IFES group compared with controls at the end of treatment sessions and 1 year later (P < 0.05). All the children had abnormal flow curves at the beginning of the study. The flow curve became normal in 14/18 (77%) of the children in the IFES group and six of 18 (33%) in the control group by the end of follow-up (P < 0.007). At the end of the treatment course, night-time wetting was improved in all children who had this symptom before the treatment in the IFES group (P < 0.01).

Conclusion

Combining IFES and urotherapy is a safe and effective therapy in the management of children with UAB.

Conjoint USANZ and UGSA Guidelines on the management of adult non-neurogenic overactive bladder

Abstract

Due to the myriad of treatment options available and the potential increase in the number of patients afflicted with overactive bladder (OAB) who will require treatment, the Female Urology Special Advisory Group (FUSAG) of the Urological Society of Australia and New Zealand (USANZ), in conjunction with the Urogynaecological Society of Australasia (UGSA), see the need to move forward and set up management guidelines for physicians who may encounter or have a special interest in the treatment of this condition. These guidelines, by utilising and recommending evidence-based data, will hopefully assist in the diagnosis, clinical assessment, and optimisation of treatment efficacy. They are divided into three sections: Diagnosis and Clinical Assessment, Conservative Management, and Surgical Management. These guidelines will also bring Australia and New Zealand in line with other regions of the world where guidelines have been established, such as the American Urological Association, European Association of Urology, International Consultation on Incontinence, and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines of the UK.