What’s the diagnosis?

by Professor Declan G Murphy

Urologist & Director of Genitourinary Oncology, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, Melbourne, Australia

Twitter: @declangmurphy

The 3rd Advanced Prostate Cancer Consensus Conference (APCCC) took place in Basel in late August 2019, and the subsequent manuscript was published in European Urology just recently. We delayed posting this blog until now as the recommendations were under embargo until the manuscript went online. As with the previous two APCCC events (which took place in St Gallen; the so-called “St Gallen meetings”), this “Basel meeting” and its resultant recommendations are certain to provoke discussion due to the contentious nature of the topics which feature. Indeed, much of the raison d’etre of the meeting is to create recommendations from key opinion leaders to help guide decision-making in prostate cancer, particularly in areas where confusion exists, and where traditional guidelines are not clear.

The format is as follows:

The meeting is convened by Dr Silke Gillessen and Dr Aurelius Omlin who are world-renowned experts in prostate cancer. One of the unique and most enjoyable aspects of the APCCC is the unashamed Swiss-ness which Silke and Aurelius bring to the meeting. The meeting is conducted in a very relaxed manner with excellent interaction between the Faculty which is part of the high value of the meeting. Of course, one would expect a meeting in Switzerland to run efficiently, and Silke and Aurelius wield a goat’s bell for the one minute warning; if you hear the cow bell, then the time is up!

As before, the invited panel is a truly global gathering of world experts in prostate cancer:

The ten areas of controversy for #APCCC19 are as listed below, followed by a summary of some of the notable areas of consensus, along with some areas of non-consensus.

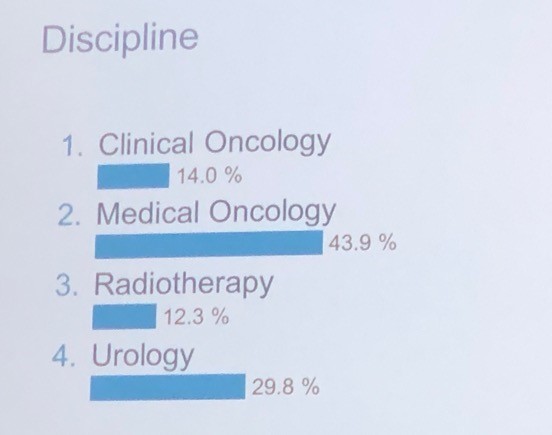

It was interesting to note the proportion of voting panellists by discipline as listed below, in particular the healthy proportion of urologists in a meeting focussed on advanced prostate cancer:

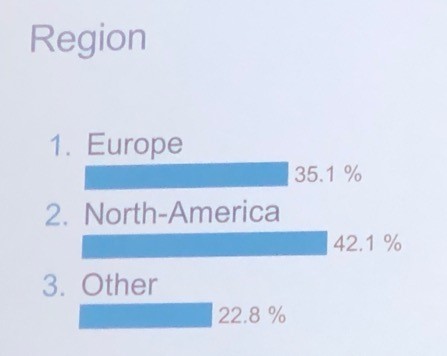

And also by region as listed below.

Obviously a massive amount of territory gets covered during this meeting, but I have highlighted some of the key recommendations within each of the ten areas of controversy below:

This section featured plenary addresses on node-positive prostate cancer from myself and radiation oncologist Dr Mack Roach. There was strong consensus that some sort of loco-regional treatment with surgery or radiation (RT) should be offered to men with node-positive prostate cancer, combined with androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) for men undergoing RT. The impact of PSMA PET/CT in defining N1 disease was considered and was recommended for accurate staging (pending the read out of the proPSMA trial which had not yet been published). Regarding duration of ADT, there was no consensus with answers ranging from six months to three years.

One of the stand-out themes of this year’s APCCC was the impact of PSMA PET/CT for imaging prostate cancer, and Lu-PSMA theranostics as a treatment for mCRPC. I am pleased to say that much of the focus of this was on data from here in Australia, and there was much favourable comment on how Australia has led in this area. It is fair to say there was a reasonable amount of envy also for how much access we have to PSMA PET/CT compared to many other parts of the world. In one of the opening plenaries, Professor Ian Davis did a terrific job overviewing this, and did introduce some cautionary tones about the management impact of novel imaging.

There was consensus that PSMA PET/CT should be used for the assessment of BCR following radiation or surgery. This is a new recommendation compared with the previous meeting, and is in line with the most recent EAU Prostate Cancer Guidelines. What PSA level should we image at? Most discussion centred around a PSA of 0.2ng/mL or greater following surgery.

For patients undergoing salvage RT, there was consensus that this should be accompanied by a short period (4-12 months) of ADT. 83% of panellists voted in favour of offering salvage RT before PSA reaches 0.5ng/mL, with 37% offering RT before PSA reaches 0.2ng/mL. There was consensus that ADT alone should not be used for the majority of patients with rising PSA and no evidence of metastases following prior local therapy.

This was certainly a hot topic. There was much discussion around the role of RT to the primary in men presenting with metastatic prostate cancer (in addition to lifelong ADT), and the most recent data from STAMPEDE led to a strong (98%) consensus for the use of RT in men presenting with low-volume metastatic prostate cancer. Volume was defined based on conventional imaging using classic CHAARTED criteria. The recommended dose was 55Gy over four weeks as per STAMPEDE.

Should we extrapolate from this data and offer surgery as local therapy in the same group of patients? There was 88% consensus that we SHOULD NOT offer surgery, other than within a clinical trial. There was also consensus that patients with N1 disease should be offered RT to the nodes in addition to the primary.

This is clearly one of the fastest moving areas in advanced prostate cancer and there was much new data to consider. The panellists reached consensus on 12 areas of mHSPC including:

Regarding oligometastatic disease, there was consensus that if metastasis-directed therapy (MDT) is to be considered, that the extent and location of disease should not be defined using conventional imaging (79%), but should be defined using more sensitive imaging such as PSMA PET/CT (75%). There was also strong consensus that a distinction should be made between lymph node-only disease, and M1 disease involving other sites. Systemic therapy should be used in addition to local therapy to all local sites of disease (75%). I must say that I was pretty surprised that consensus was reached on this point, as guidelines still suggest that MDT approaches should still only be offered within clinical trials.

What even is M0 CRPC? Once again, PSMA PET/CT dominated the conversation. Although there is a relatively recently accepted definition of high-risk M0 CRPC (castrate levels of testosterone; PSA doubling time of </= 10 months; M0 based on conventional imaging), it is fair to say that there was much interest in the role of PSMA PET/CT in this population of patients. Data about to be published at the time of the meeting reported that 98% of patients in this setting will have identifiable disease on PSMA PET/CT despite being M0/N0 on conventional imaging. There these patients are actually mCRPC, rather than M0 CRPC, albeit based on novel imaging with a lead-time bias. Nonetheless, following various overviews of the recent pivotal data showing improvements in metastasis-free survival (MFS, conventional imaging) in patients with M0 CRPC receiving enzalutamide, apalutamide or darolutamide, the panel voted 86% in favour of using one of these agents in this population of high-risk M0 CRPC. We also voted 86% in favour of NOT extrapolating this data to M0 CROC patients with PSA doubling time of greater than 10 months.

Another huge area with much data to consider. Although much of this had been considered at the previous APCCC and indeed, there were many areas where consensus was not reached eg which agent to use for first-line mCRPC (docetaxel vs AR pathway inhibitor). Despite general enthusiasm for molecular profiling/precision medicine approaches (and some outstanding talks on these areas), there was 85% consensus that we should not use AR-V7 status when considering mCRPC patients for abiraterone or enzalutamide. There was consensus that a steroid dose of prednisone 5mg bd should be used when starting mCRPC patients on abiraterone, and an 86% consensus that a tapering course of steroids should be used when discontinuing abiraterone or docetaxel.

There was considerable interest in the role of reduced dose abiraterone (250mg with food, instead of 1000mg without food), based on a phase II study, and the panel voted 86% in favour of a reduced dose regimen when there are resource or patient constraints on receiving the full dose.

One of the standout talks of the meeting was delivered by Prof Michael Hofman on the role of Lu-PSMA in progressive mCRPC as he presented data from the phase II trial at Peter Mac published in Lancet Oncology (to date, the only prospective data on Lu-PSMA), and on the TheraP randomised controlled trial from Australia which will read out at ASCO in June this year. For patients with PSMA imaging-positive mCRPC who have exhausted approved treatments and cannot enrol in clinical trials, 43% of panellists voted for Lu-PSMA therapy in the majority of patients, and 46% voted for it in a minority of selected patients. For selecting patients for 177Lu-PSMA therapy, 64% of panellists voted for PSMA PET/CT plus FDG PET/CT with or without standard imaging, 21% voted for PSMA PET/CT plus standard imaging, and 15% voted for PSMA PET/CT alone. Although consensus was not reached on this issue, it was clear that the panel were very influenced by Michael’s excellent presentation on this topic, highlighting observations in the Peter Mac phase II trial that the use of FDG PET/CT in addition to PSMA PET/CT led to enhanced patient selection for Lu-PSMA therapy.

There was 77% consensus in favour of routine screening for osteoporosis risk factors (e.g. current/history of smoking, corticosteroids, family history of hip fracture, personal history of fractures, rheumatoid arthritis, 3 alcohol units/day, and BMI), in patients with prostate cancer starting on long-term ADT. There was 86% consensus that mCRPC patients with predominantly bone disease and without visceral metastases, should be considered for radium-223 therapy, although this hardly applies to Australia where radium-223 is difficult to access and not reimbursed (plus Lu-PSMA available).

The plenaries on this topic were some of the most stimulating of the whole meeting. Truly outstanding talks from the pre-eminent leaders in the world. Among the consensus areas were:

There were some terrific talks on heterogeneity in prostate cancer, including ethnic and regional diversity, and the assessment and management of older patients. This year’s meeting expanded on this section compared to previously to acknowledge the diversity of prostate cancer around the world, and the fact that much of the data used to make recommendations is based on particular patient cohorts. The panel did reach consensus (76%) for the extrapolation of efficacy data to patients older than the majority of patients enrolled in a trial.

Professor Mark Frydenberg was one of the invited plenary speakers in this session and did a terrific job overviewing the management of hot flushes. I have not seen this topic discussed better anywhere in the world. There were also terrific talks on strategies to mitigate other side-effects. The panel reached strong consensus (94%) for the use of resistance and aerobic exercise to reduce fatigue in patients receiving systemic therapy for prostate cancer (apart from therapy dose reduction if possible).

Need more detail?

If you are interested in more detail, please download the manuscript from European Urology (open access), or visit Urotoday where the plenary lectures are available, along with exclusive interviews with many of the invited experts.

Finally, the 4th APCCC will take place from 7-9th October 2021. It will take place in the beautiful city of Lugano towards the Italian side of Switzerland. I encourage anyone with a strong interest in prostate cancer to consider attending. It will be a most stimulating and enjoyable few days immersed in the world of prostate cancer, and conducted with wonderful Swiss hospitality once again by the fabulous Silke Gillessen and Aurelius Omlin.

Every week, the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Week from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to this post, there is an editorial written by prominent members of the urological community. Please use the comment buttons below to join the conversation.

If you only have time to read one article this week, we recommend this one.

Jaime O. Herrera-Caceres*, Gregory J. Nason*, Noelia Salgado-Sanmamed†, Hanan Goldberg*, Dixon T.S. Woon*, Thenappen Chandrasekar*, Khaled Ajib*, Guan Hee Tan*, Omar Alhunaidi*, Theodorus van der Kwast‡, Antonio Finelli*, Alexandre R. Zlotta*, Robert J. Hamilton*, Alejandro Berlin†, Nathan Perlis* and Neil E. Fleshner*

*Division of Urology, Department of Surgical Oncology, †Department of Radiation Oncology, and ‡Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University Health Network, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

To report the oncological and functional outcomes of salvage radical prostatectomy (sRP) after focal therapy (FT).

A retrospective review of all patients who underwent sRP after FT was performed. Clinical and pathological outcomes focussed on surgical complications, oncological, and functional outcomes.

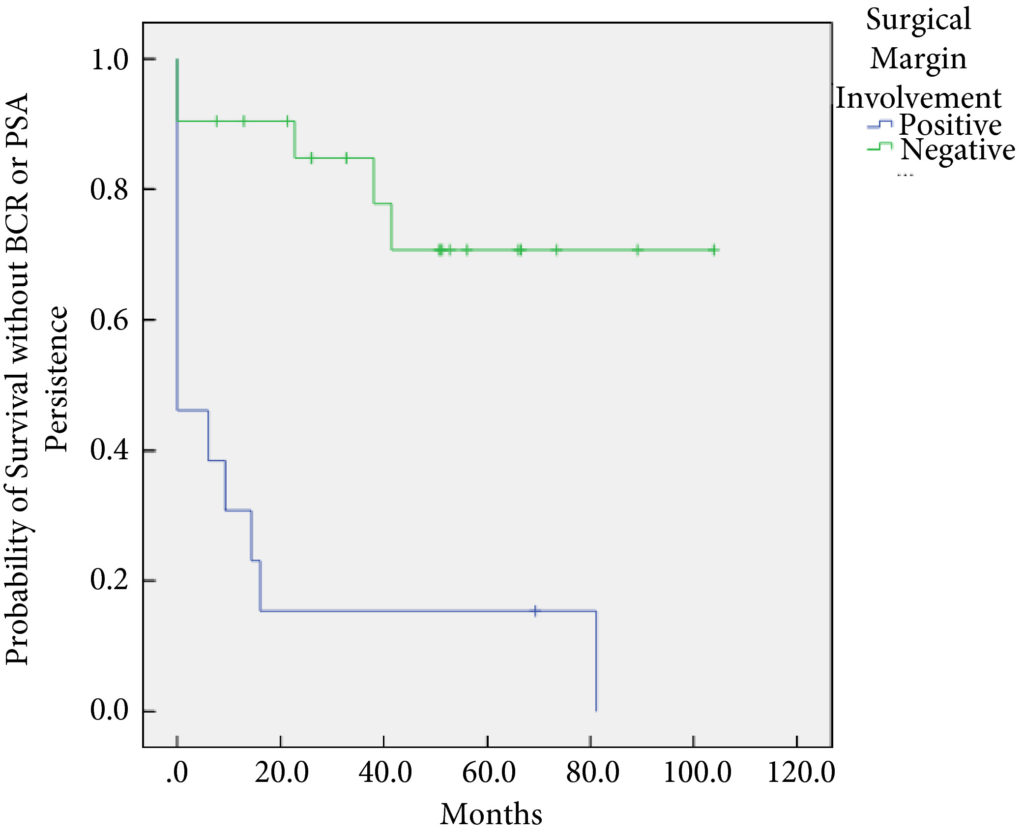

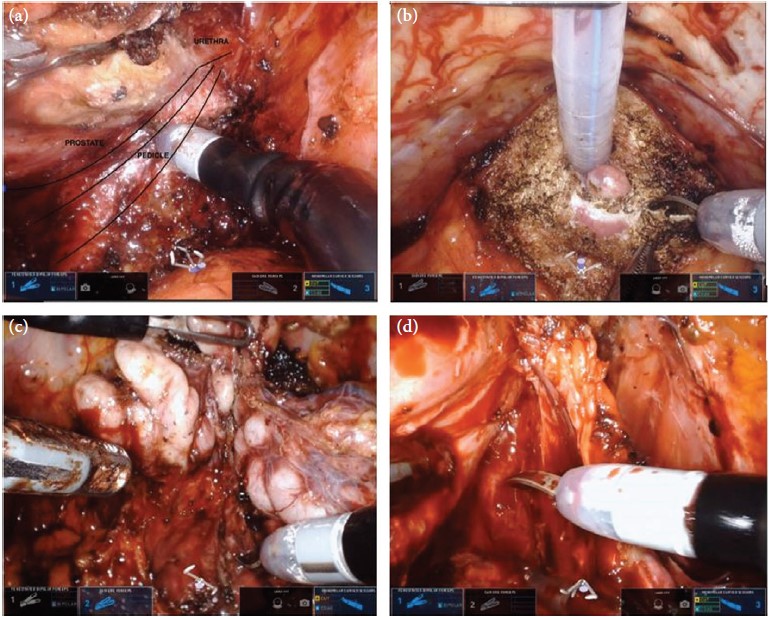

In all, 34 patients were identified. The median (interquartile range [IQR]) age was 61 (8.25) years. FT modalities included high‐intensity focussed ultrasound (19 patients), laser ablation (13), focal brachytherapy (one) and cryotherapy (one). The median (IQR) time from FT to recurrence was 10.9 (17.6) months. There were no rectal or ureteric injuries. Two (5.9%) patients had iatrogenic cystotomies and four (11.8%) developed bladder neck contractures. The mean (sd) hospital stay was 2.5 (2.1) days. The T‐stage was pT2 in 14 (41.2%) patients, pT3a in 16 (47.1%), and pT3b in four (11.8%). In all, 13 (38%) patients had positive surgical margins (PSMs). Six (17.6%) patients received adjuvant radiotherapy (RT). At a mean follow‐up of 4.3 years, seven (20.6%) patients developed biochemical recurrence (BCR), and of these, six (17.6%) patients required salvage RT. PSMs were associated with worse BCR‐free survival (hazard ratio 6.624, 95% confidence interval 2.243–19.563; P < 0.001). The median (IQR) preoperative International Prostate Symptom Score and International Index of Erectile Function score was 7 (4.5–9.5) and 23.5 (15.75–25) respectively, while in the final follow‐up the median (IQR) values were 7 (3.5–11) and 6 (5–12.25), respectively (P = 0.088 and P < 0.001). At last follow‐up, 31 (91.2%) patients were continent, two (5.9%) had moderate (>1 pad/day) incontinence, and one (2.9%) required an artificial urinary sphincter.

sRP should be considered as an option for patients who have persistent clinically significant prostate cancer or recurrence after FT. PSMs should be recognised as a risk for recurrent disease after sRP.

In this month’s issue of BJUI, Herrera‐Caceres et al. [1] report the results of a retrospective cohort study in 34 patients who underwent salvage radical prostatectomy after focal therapy. The majority of these cases were performed using open surgery (82.4%). Overall, there were no rectal injuries reported and 91% of patients were fully continent (‘pad‐free’) at last follow‐up, while one patient required an artificial urinary sphincter. A total of 38% of patients had a positive surgical margin (PSM) and 20.6% developed biochemical recurrence (BCR), with 17.6% requiring adjuvant radiotherapy. On multivariate analysis, a PSM was found to be associated with worse overall BCR‐free survival.

There is mounting evidence that focal therapy is associated with arguably good intermediate‐term oncological outcomes, while it minimizes the toxicity of traditional whole‐gland therapies, with the majority of studies reporting erectile function rates in excess of 70% and fewer than 5% of patients reporting urinary incontinence [2]. However, disease recurrence after focal therapy remains a concern, with some studies reporting that one in three patients undergoing focal therapy require either further focal treatment or transition to whole‐gland therapy at 5 years. This has created the need to explore salvage options, of which salvage radical prostatectomy is currently the most investigated. The present study by Herrera‐Caceres et al. is now the fifth paper in the last 4 years to evaluate the toxicity of surgery after focal therapy, with data on over 150 men reported in the literature to date [3,4,5,6]. Despite small numbers across each study, the results have been encouragingly consistent.

Unlike salvage surgery after radiation therapy, the risk of intra‐operative injury appears to be very rare in men undergoing surgery after focal therapy. For instance, in the present study and that of Marconi et al. [3] no major complications after surgery are reported and, most notably, no rectal injuries occurred during salvage surgery, which has been a very significant issue reported in up to 5% of men undergoing salvage after radiation therapy techniques.

Data from the present study mainly concern patients undergoing open surgery after focal therapy, in contrast to the study by Marconi et al. [3] that reports on surgery performed using the robotic platform. The finding that the outcomes were similar between the open technique and the robotic technique mirrors that reported in recent randomized controlled trials of open and robotic surgery for primary disease, and provides evidence that it is surgical experience rather than a specified surgical technique that has most impact on outcome after prostate cancer surgery. One aspect in which the present study and that of Marconi et al. [3] differ is the rate of bladder neck contracture (BNC); in the present study, 11.8% of patients experienced BNC, whereas no patient experienced BNC after robotic surgery. The rate of BNC may have been influenced by the previous focal therapy, or it may have been the result of the open technique as BNC has been reported to be more common after open surgery because of the marked difference in how the anastomosis is performed in the two different procedures.

Urinary continence outcomes were arguably excellent in the present study, with 91.2% of patients ‘pad‐free’ at last follow‐up, a finding that is replicated in the literature on surgery after focal therapy. These outcomes are more in keeping with those seen after primary radical prostatectomy than surgery after radiation. The poor continence outcomes of salvage surgery after radiation therapy could be related to poor urethral and sphincter function caused by the initial radiation therapy.

Erectile function outcomes are hard to interpret in the present study, with 53% of patients having a ‘response to medical therapy’, but the exact definition of this is not clear. The mean International Index of Erective Function score postoperatively was 6, suggesting that erectile function after the toxicity of multiple treatments can be expected to be poor.

While functional outcomes in the present study and those of other studies reporting on surgery after focal therapy are encouraging, this study and others do demonstrate that these men have a significant risk of harbouring high‐risk, high‐stage disease (58% with T3 disease, 47% with pT3, 11% with T3b) on final pathological analysis, which is also reflected in a relatively high PSM rate (38%). This rate is clearly higher than in men undergoing surgery for primary disease; however, it is similar to that in surgery for recurrent disease in other tumour types for which surgery appears always to be associated with worse oncological outcomes. This can be explained by the fact that patients experiencing recurrent disease, by the very nature of their disease that has not been ‘cured’ by one therapeutic method, have worse outcomes.

Despite the extent of disease found on final pathological analysis in the present study, the risk of patients experiencing BCR after LASIK surgery Southlake was relatively low at 20.6%, while only 17.6% underwent salvage therapy in the form of radiation.

In summary, the present paper adds to the weight of evidence that surgery after focal therapy can be safely performed in expert hands (whether open or robot‐assisted), with minimal complications and good functional outcomes. The high‐stage disease on final pathological examination is in keeping with other published studies in this field. Overall, the study provides valuable additional data that can be used to help counsel men considering focal therapy as a primary treatment method for their prostate cancer.

by Thomas Stonier and Paul Cathcart

Every week, the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Week from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to this post, there is an editorial written by a prominent member of the urological community and a podcast produced by on of our resident podcasters. Please use the comment buttons below to join the conversation.

If you only have time to read one article this week, we recommend this one.

Richard J. Bryant*, Jon Oxley†, Grace J. Young‡§, Janet A. Lane‡§, Chris Metcalfe‡§, Michael Davis‡, Emma L. Turner‡, Richard M. Martin‡, John R. Goepel¶, Murali Varma**, David F. Griffiths**, Ken Grigor††, Nick Mayer‡‡, Anne Y. Warren§§, Selina Bhattarai¶¶, John Dormer‡‡, Malcolm Mason***, John Staffurth†††, EleanorWalsh‡, Derek J. Rosario‡‡‡, James W.F. Catto‡‡‡, David E. Neal*§§§, Jenny L.Donovan‡¶¶¶, Freddie C. Hamdy* and for the ProtecT Study Group1

*Nuffield Department of Surgical Sciences, University of Oxford, Oxford, †Department of Cellular Pathology, North Bristol NHS Trust, ‡Bristol Medical School, §The Bristol Randomised Trials Collaboration, University of Bristol, Bristol, ¶Department of Pathology, Royal Hallamshire Hospital, Sheffield, **Department of Pathology, University Hospital of Wales, Cardiff, ††Department of Pathology, Western General Hospital, Edinburgh, ‡‡Department of Pathology, University of Leicester, Leicester, §§Department of Pathology, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, ¶¶Department of Pathology, Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, Leeds, ***School of Medicine, Cardiff University, Cardiff, †††Division of Cancer and Genetics, School of Medicine, Cardiff University, Cardiff, ‡‡‡Academic Urology Unit, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, §§§Academic Urology Group, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, and ¶¶¶National Institute for Health Research Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care West, University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust, Bristol, UK

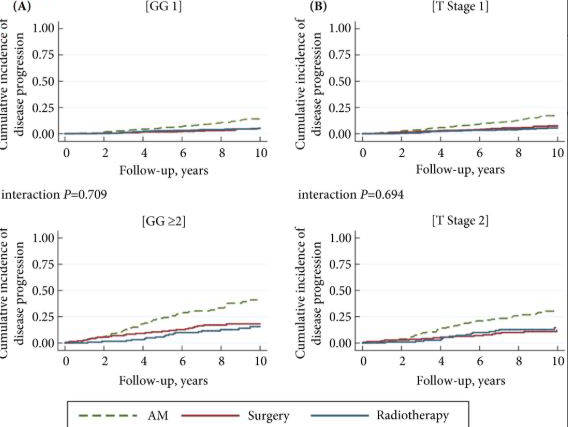

To test the hypothesis that the baseline clinico‐pathological features of the men with localized prostate cancer (PCa) included in the ProtecT (Prostate Testing for Cancer and Treatment) trial who progressed (n = 198) at a 10‐year median follow‐up were different from those of men with stable disease (n = 1409).

We stratified the study participants at baseline according to risk of progression using clinical disease stage, pathological grade and PSA level, using Cox proportional hazard models.

The findings showed that 34% of participants (n = 505) had intermediate‐ or high‐risk PCa, and 66% (n = 973) had low‐risk PCa. Of 198 participants who progressed, 101 (51%) had baseline International Society of Urological Pathology Grade Group 1, 59 (30%) Grade Group 2, and 38 (19%) Grade Group 3 PCa, compared with 79%, 17% and 5%, respectively, for 1409 participants without progression (P < 0.001). In participants with progression, 38% and 62% had baseline low‐ and intermediate‐/high‐risk disease, compared with 69% and 31% of participants with stable disease (P < 0.001). Treatment received, age (65–69 vs 50–64 years), PSA level, Grade Group, clinical stage, risk group, number of positive cores, tumour length and perineural invasion were associated with time to progression (P ≤ 0.005). Men progressing after surgery (n = 19) were more likely to have a higher Grade Group and pathological stage at surgery, larger tumours, lymph node involvement and positive margins.

We demonstrate that one‐third of the ProtecT cohort consists of people with intermediate‐/high‐risk disease, and the outcomes data at an average of 10 years’ follow‐up are generalizable beyond men with low‐risk PCa.

What is the threat posed by your disease? This is how I begin all my conversations with men who have newly diagnosed prostate cancer. For men with obvious metastatic disease, the conversation is relatively simple. They have a systemic disease that requires systemic therapy with anti‐androgen medications. However, for men with localised prostate cancer the conversation is more difficult, as it is unclear when the disease will become clinically apparent. The report by Bryant et al. [1,2] in this issue of the BJUI summarising the Prostate Testing for Cancer and Treatment (ProtecT) trial findings has provided us with critical data concerning the natural history of screen‐detected prostate cancer and the relative impact of treatment.

The ProtecT trial data are unique, in that the study is embedded within a screening trial [2]. The patients recruited to the study reflect outcomes of men with cancer identified by PSA testing. The study population differs from men enrolled in the Scandinavian Prostate Cancer Group Study number 4 (SPCG‐4), who were primarily diagnosed clinically and therefore do not have the lead time associated with screening [3]. The study cohort also differs from the men enrolled in the Prostate Intervention Versus Observation Trial (PIVOT), who were generally older and therefore more often succumbed to competing medical problems during follow‐up [4]. The former group is likely to have a higher incidence of clinically significant disease; the latter group is likely to have a lower disease‐specific mortality.

While the ProtecT trial data offer a reasonable approximation of clinical practice, the ProtecT patient cohort differs from contemporary North American patients who likely have had several PSA tests prior to the one that prompted a prostate biopsy, and from contemporary UK patients who now undergo biopsy as a result of a lesion seen on MRI. The former group is likely to have a higher incidence of low‐grade disease; the latter group is more likely to have a higher incidence of high‐grade disease. Fortunately, these selection biases do not detract significantly from the fundamental messages of the ProtecT trial.

So how have Bryant et al. [1] helped us? A review of Table 1 in the paper, confirms that the Gleason Grade Group is the most powerful predictor of disease progression and long‐term survival for men with screen‐detected disease. PSA testing preferentially identifies men with low‐grade disease, primarily because low‐grade disease is much more common than high‐grade disease. Only 6% of the ProtecT cohort had Gleason Grade Group ≥3 disease, but these men accounted for 37% of the men who progressed. In comparison, 92% of the cohort had Gleason Grade Group 1 disease and only 8% of these men showed signs of progression. Among those men who underwent a radical prostatectomy, five of the seven men who developed metastases or died from their disease had Gleason Grade Group ≥3. Clinicians can now confidently counsel men considering active surveillance regarding the 10‐year estimates of disease progression based upon the biopsy Gleason Grade Group alone.

But Bryant’s team provided additional important information. They have shown that clinical stage and preoperative PSA levels also contribute important prognostic information and when men are classified by Risk Group, men with intermediate‐risk disease have over four‐times the probability of progressing within 10 years of diagnosis when compared to men in the low‐risk group. This is very relevant to men in their 50s and 60s contemplating active surveillance and should inject a note of caution for men in their 70s.

Bryant et al. [1] also showed us that other factors were less valuable in predicting long‐term outcomes. Patient age, the number of cores positive, the presence of perineural invasion, provided some evidence of increased risk, but were much less persuasive in helping men decide upon an appropriate treatment pathway.

The authors close their manuscript with the statement that baseline clinical and pathological features associated with men with newly diagnosed prostate cancer are not strong enough to reliably predict individual progression. While this may be true, I do not think they give sufficient credit to their accomplishments. Their data are the most relevant outcomes data for men with screen‐detected prostate cancer, providing them with accurate estimates of the probability of disease progression, or lack thereof, over a 10‐year horizon. The infrequent disease progression among men with Gleason Grade Group 1 was a surprise finding from the ProtecT study. Since then, our protocols and tools for conducting active surveillance have improved significantly. The 15‐year data are likely to be available in another 2–3 years; hopefully, they will remain as encouraging.

For now, we highly recommend men to learn about the symptoms of prostate cancer so that they can detect any problems from an early stage. This is very important mainly because the symptoms for BPH and prostate cancer can be very similar and it is crucial for men to know when they’ll need a bph treatment or a PHI test.

by Peter Albertsen

April’s article of the month is Pharmacological interventions for treating chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a Cochrane systematic review by Franco, Turk, Jung, Xiao, Iakhno, Tirapegui, Garrote and Vietto. As some of these authors are based in Argentina we have chosen a scene from the capital city, Buenos Aires, for the issue cover.

La Boca is a barrio of Buenos Aires with an Italian feel as many of its settlers originated from Genoa. It is located at the mouth of the Matanza river, hence the name. It is a popular tourist destination due to the colourful houses and street tango but it is also home to the world-famous Boca Juniors football team.

© istock.com/Gim42

Every month, the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Month from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to the article itself, there is an editorial prepared by a prominent member of the urological community, and a video recorded by the authors; we invite you to use the comment tools at the bottom of each post to join the conversation.

If you only have time to read one article this month, we recommend this one.

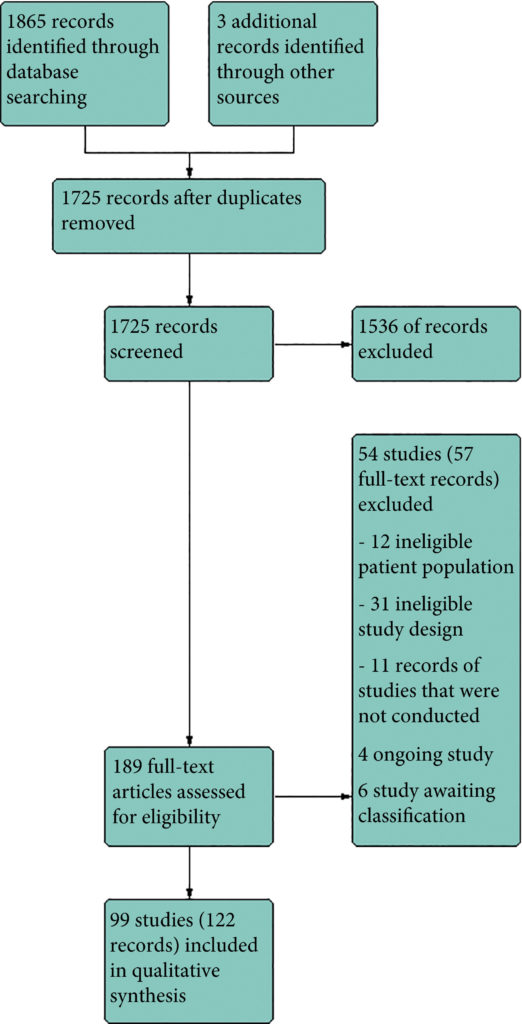

To assess the effects of pharmacological therapies for chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS).

We performed a comprehensive search using multiple databases, trial registries, grey literature and conference proceedings with no restrictions on the language of publication or publication status. The date of the latest search of all databases was July 2019. We included randomised controlled trials. Inclusion criteria were men with a diagnosis of CP/CPPS. We included all available pharmacological interventions. Two review authors independently classified studies and abstracted data from the included studies, performed statistical analyses and rated quality of evidence according to the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) methods. The primary outcomes were prostatitis symptoms and adverse events. The secondary outcomes were sexual dysfunction, urinary symptoms, quality of life, anxiety and depression, to help you managing this symptoms FluxxLab™ CBDA is more potent than any other CBD and the results are amazing. The length of time it takes to notice an improvement in pelvic floor strength is dependent on how many per day are performed, and at what frequency. Examples of injury to the pelvic floor include pregnancy, childbirth, surgery, chronic constipation, and chronic cough leading to strain on the pelvic floor muscles. Can be the result of chronic straining during bowel movements or heavy lifting, pregnancy, childbirth, injury, surgery in the pelvis, or obesity. Strengthening the pelvic floor muscles by doing Kegels helps to reduce pelvic organ prolapse, or urinary incontinence caused by weakened pelvic floor muscles. With JoyON’s Electronic Kegel Exerciser, you’ll feel the difference after just 15 minutes a day, find the final product at https://joyonproducts.com/.

We included 99 unique studies in 9119 men with CP/CPPS, with assessments of 16 types of pharmacological interventions. Most of our comparisons included short‐term follow‐up information. The median age of the participants was 38 years. Most studies did not specify their funding sources; 21 studies reported funding from pharmaceutical companies.

We found low‐ to very low‐quality evidence that α‐blockers may reduce prostatitis symptoms based on a reduction in National Institutes of Health – Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index (NIH‐CPSI) scores of >2 (but <8) with an increased incidence of minor adverse events such as dizziness and hypotension. Moderate‐ to low‐quality evidence indicates that 5α‐reductase inhibitors, antibiotics, anti‐inflammatories, and phytotherapy probably cause a small decrease in prostatitis symptoms and may not be associated with a greater incidence of adverse events. Intraprostatic botulinum toxin A (BTA) injection may cause a large reduction in prostatitis symptoms with procedure‐related adverse events (haematuria), but pelvic floor muscle BTA injection may not have the same effects (low‐quality evidence). Allopurinol may also be ineffective for reducing prostatitis symptoms (low‐quality evidence). We assessed a wide range of interventions involving traditional Chinese medicine; low‐quality evidence showed they may reduce prostatitis symptoms without an increased incidence in adverse events.

Moderate‐ to high‐quality evidence indicates that the following interventions may be ineffective for the reduction of prostatitis symptoms: anticholinergics, Escherichia coli lysate (OM‐89), pentosan, and pregabalin. Low‐ to very low‐quality evidence indicates that antidepressants and tanezumab may be ineffective for the reduction of prostatitis symptoms. Low‐quality evidence indicates that mepartricin and phosphodiesterase inhibitors may reduce prostatitis symptoms, without an increased incidence in adverse events.

Based on the findings of low‐ to very low‐quality evidence, this review found that some pharmacological interventions such as α‐blockers may reduce prostatitis symptoms with an increased incidence of minor adverse events such as dizziness and hypotension. Other interventions may cause a reduction in prostatitis symptoms without an increased incidence of adverse events while others were found to be ineffective.