What was the diagnosis?

Welcome to our #incaseyoumissedit series

Welcome to our #incaseyoumissedit series

Every week, the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Week from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to this post, there is an editorial written by a prominent member of the urological community and a video produced by the authors. Please use the comment buttons below to join the conversation.

If you only have time to read one article this week, we recommend this one.

Masaki Yoshida*, Masayuki Takeda†, Momokazu Gotoh‡, Osamu Yokoyama§, Hidehiro Kakizaki¶, Satoru Takahashi**, Naoya Masumori††, Shinji Nagai‡‡ and Kazuyoshi Minemura‡‡

*Department of Urology, National Centre for Geriatrics and Gerontology, Obu, †Department of Urology, University of Yamanashi, Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Kofu, Japan, ‡Department of Urology, Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine, Nagoya, §Department of Urology, Faculty of Medical Science, University of Fukui, Fukui, ¶Department of Renal and Urological Surgery, Asahikawa Medical University, Asahikawa, Japan, **Department of Urology, Nihon University School of Medicine, Tokyo, ††Department of Urology, Sapporo Medical University School of Medicine, Sapporo, and ‡‡Kyorin Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan

To evaluate the efficacy of a novel and selective β3‐adrenoreceptor agonist vibegron on urgency urinary incontinence (UUI) in patients with overactive bladder (OAB).

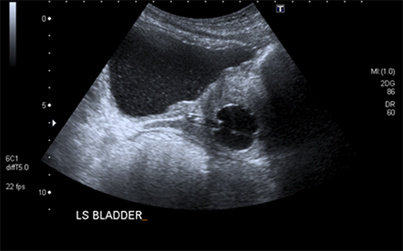

A post hoc analysis was performed in patients with UUI (>0 episodes/day) who were assigned to receive vibegron or placebo in a vibegron phase 3 study. Patients were subclassified into mild/moderate (>0 to <3 UUI episodes/day) or severe UUI (≥3 UUI episodes/day) subgroup. Changes from baseline in number of UUI episodes/day, in number of urgency episodes/day, and in voided volume/micturition were compared between the groups. The percentage of patients who became UUI‐free (‘diary‐dry’ rate) and the response rate (percentage of patients with scores 1 [feeling much better] or 2 [feeling better] assessed by the Patient Global Impression scale [PGI]) were evaluated.

Changes in numbers of UUI episodes at week 12 in the vibegron 50 mg, vibegron 100 mg and placebo groups, respectively, were −1.35, −1.47 and −1.08 in all patients, −1.04, −1.13 and −0.89 in the mild/moderate UUI subgroup, and −2.95, −3.28 and −2.10 in the severe UUI subgroup. The changes were significant in the vibegron 50 and 100 mg groups vs placebo regardless of symptom severity. Change in number of urgency episodes/day was significant in the vibegron 100 mg group vs placebo in all patients and in both severity subgroups. In the vibegron 50 mg group, a significant change vs placebo was observed in all patients and in the mild/moderate UUI subgroup. Change in voided volume/micturition was significantly greater in the vibegron 50 and 100 mg groups vs placebo in all patients, as well as in the both severity subgroups. Diary‐dry rates in the vibegron 50 and 100 mg groups were significantly greater vs placebo in all patients and in the mild/moderate UUI subgroup. In the severe UUI subgroup, however, a significant difference was observed only in the vibegron 50 mg group. Response rates assessed by the PGI were significantly higher in the vibegron groups vs placebo in all patients and in the both severity subgroups. Vibegron administration, OAB duration ≤37 months, mean number of micturitions/day at baseline <12.0 and mean number of UUI episodes/day at baseline <3.0 were identified as factors significantly associated with normalization of UUI.

Vibegron, a novel β3‐adrenoreceptor agonist, significantly reduced the number of UUI episodes/day and significantly increased the voided volume/micturition in patients with OAB including those with severe UUI, with the response rate exceeding 50%. These results suggest that vibegron can be an effective therapeutic option for OAB patients with UUI.

Every week, the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Week from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to this post, there is an editorial written by a prominent member of the urological community and a video produced by the authors. Please use the comment buttons below to join the conversation.

If you only have time to read one article this week, we recommend this one.

Ola Bratt*†, Linda Drevin‡, Karl-Göran Prütz§, Stefan Carlsson¶, Lars Wennberg** and Pär Stattin††

*Department of Urology, Institute of Clinical Science, Sahlgrenska Academy, Gothenburg University, †Department of Urology, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg, ‡Regional Cancer Centre, Uppsala-Orebro, Uppsala, §Swedish Renal Registry, Ryhov Hospital, Jönköping, ¶Section of Urology, Department of Molecular Medicine and Surgery, Karolinska Institute, **Department of Transplantation Surgery, Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, and ††Department of Surgical Sciences, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden

To investigate whether post‐transplantation immunosuppression negatively affects prostate cancer outcomes in male kidney transplant recipients.

We used the Swedish Renal Register and the National Prostate Cancer Register to identify all kidney transplantation recipients diagnosed with prostate cancer in Sweden 1998–2016. After linking these registers with Prostate Cancer Database Sweden (PCBaSe), a case‐control study was designed to compare time period and risk category‐specific probabilities of a prostate cancer diagnosis amongst kidney transplantation recipients versus the male general population. The registers did not include information about the specific immunosuppression agent used in all transplantation recipients. Data from PCBaSe were used to compare prostate cancer characteristics at diagnosis and survival for patients with prostate cancer with versus without a kidney transplant. Propensity score matching, Cox regression analysis and Fisher’s exact test were used and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) calculated.

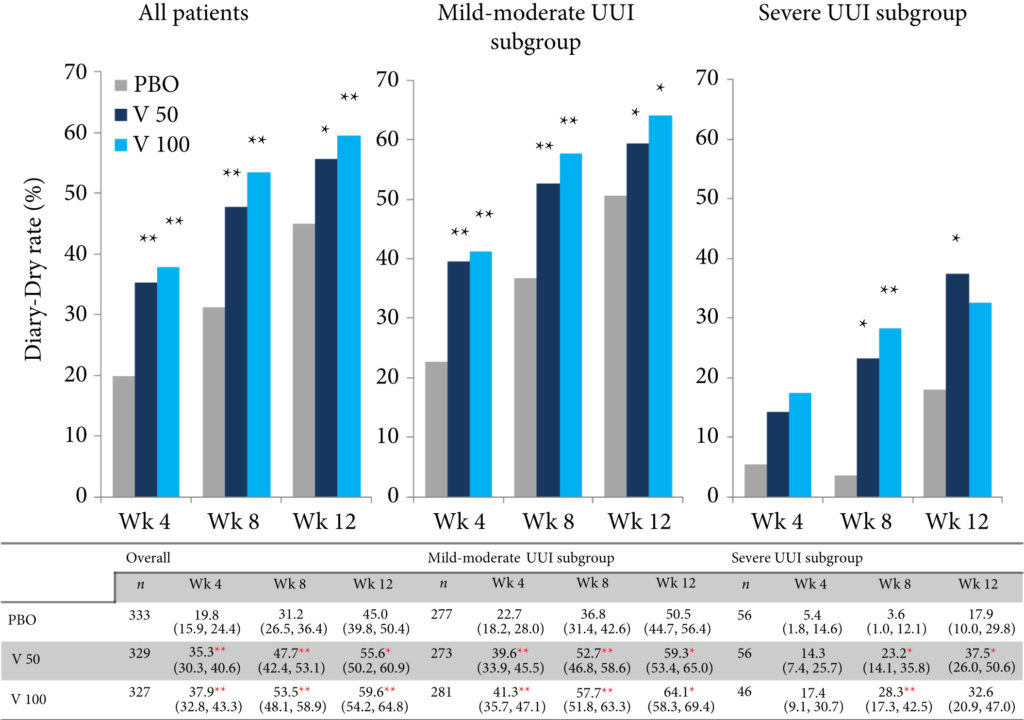

Almost half of the 133 kidney transplantation recipients were transplanted before the mid‐1990s, when PSA testing became common in cancer centers. The transplant recipients were not more likely than age‐matched control men to be diagnosed with any (odds ratio [OR] 0.84, 95% CI 0.70–0.99) or high‐risk or metastatic prostate cancer (OR 0.84, 95% CI 0.62–1.13). None of the ORs for the different categories of prostate cancer increased with time since transplantation. Cancer characteristics at the time of diagnosis and cancer‐specific survival were similar amongst transplant recipients and the control group of 665 men diagnosed with prostate cancer without a kidney transplant.

This Swedish nationwide, register‐based study gave no indication that immunosuppression after kidney transplantation increases the risk of prostate cancer or adversely affects prostate cancer outcomes. The study suggests that men with untreated low‐grade prostate cancer can be accepted for transplantation.

Untreated prostate cancer is generally a contraindication to kidney transplantation. At our institution in Boston, we are often referred individuals with low‐volume low‐risk prostate cancer for treatment. For a cancer that would otherwise be managed with active surveillance, these kidney transplantation candidates will often be forced into some form of definitive therapy, generally radical prostatectomy, a procedure with a well‐known long‐term side‐effect profile, and then have to wait for a period of time, generally 2 years, before being considered for transplantation. The basis for this approach stems from the theoretical higher risk of disease progression and ultimately mortality on immunosuppression. In this issue of the BJU International, Bratt et al. [1] challenge these assumptions and report on the outcomes of kidney transplant recipients diagnosed with prostate cancer. First, they found no difference in prostate cancer incidence, suggesting that transplant recipients, despite being immunosuppressed, are not at higher risk of prostate cancer. Second, they found that the prostate cancer characteristics at diagnosis, overall and prostate cancer‐specific survival of kidney transplant recipients do not differ significantly from non‐transplant patients. Furthermore, the probability of developing advanced prostate cancer over time was not higher among transplant recipients on immunosuppression. Taken together, these findings show that transplant patients are not at a higher risk of poor prostate cancer outcomes.

Hypothesising that many of the transplant recipients in this study already had prostate cancer when they underwent transplantation (based on assumptions about cancer screening practices in Sweden and the time periods included), the authors aim to refute current transplantation guidelines contraindicating solid organ transplantation in those with a history of prostate cancer and requiring a minimum recurrence‐free period before placing these patients on the organ waiting list [2, 3]. The findings of Bratt et al. [1] corroborate previous case series including the largest study of cancer incidence among transplant recipients and a meta‐analysis of six studies. Given the available data, is it still justifiable to deny patients with low‐risk prostate cancer life‐saving kidney transplantation? If the answer is ‘no’, what would be fair cutoffs in Gleason score, number of positive biopsy cores, PSA level, time from diagnosis, etc.? While this study does not definitely answer the question, it would seem reasonable that candidates for active surveillance, especially those with very low‐risk prostate cancer, should be eligible for kidney transplantation without prior definitive therapy. Denying immediate placement on the waiting list represents not only a significant reduction of quality of life, but also leads to reduced survival due to longer dialysis time.

Another concern often heard from those in favour of definitive therapy before transplantation is the added risks of prostatectomy in immunosuppressed individuals; this is understandable given that the incidence of definitive therapy on active surveillance is ~50% at 10 years after diagnosis [4]. However, the available data suggest that prostatectomy after transplantation is safe. For example, in a recent systematic review, only one of 35 patients had a Clavien ≥ 3 complication and graft function was maintained in all patients [5]

To summarise, this study [1], and others before that, suggests that immunosuppression after kidney transplantation is unlikely to adversely affect prostate cancer initiation or progression. Men with low‐risk prostate cancer should be considered for transplantation without first undergoing definitive therapy. There is evidence around the world, and at our institution, that transplant specialists are finally starting to accept this pathway. This study will further reinforce this concept.

by Lorine Haeuser, David‐Dan Nguyen Quoc‐Dien Trinh

:

To investigate whether post‐transplantation immunosuppression negatively affects prostate cancer outcomes in male kidney transplant recipients.

We used the Swedish Renal Register and the National Prostate Cancer Register to identify all kidney transplantation recipients diagnosed with prostate cancer in Sweden 1998–2016. After linking these registers with Prostate Cancer Database Sweden (PCBaSe), a case‐control study was designed to compare time period and risk category‐specific probabilities of a prostate cancer diagnosis amongst kidney transplantation recipients versus the male general population. The registers did not include information about the specific immunosuppression agent used in all transplantation recipients. Data from PCBaSe were used to compare prostate cancer characteristics at diagnosis and survival for patients with prostate cancer with versus without a kidney transplant. Propensity score matching, Cox regression analysis and Fisher’s exact test were used and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) calculated.

Almost half of the 133 kidney transplantation recipients were transplanted before the mid‐1990s, when PSA testing became common. The transplant recipients were not more likely than age‐matched control men to be diagnosed with any (odds ratio [OR] 0.84, 95% CI 0.70–0.99) or high‐risk or metastatic prostate cancer (OR 0.84, 95% CI 0.62–1.13). None of the ORs for the different categories of prostate cancer increased with time since transplantation. Cancer characteristics at the time of diagnosis and cancer‐specific survival were similar amongst transplant recipients and the control group of 665 men diagnosed with prostate cancer without a kidney transplant.

This Swedish nationwide, register‐based study gave no indication that immunosuppression after kidney transplantation increases the risk of prostate cancer or adversely affects prostate cancer outcomes. The study suggests that men with untreated low‐grade prostate cancer can be accepted for transplantation.

Every week, the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Week from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to this post, there is an editorial written by a prominent member of the urological community. Please use the comment buttons below to join the conversation.

If you only have time to read one article this week, we recommend this one.

Rebecca Robbins*, Girardin Jean‐Louis†, Nicholas Chanko†, Penelope Combs†, Nataliya Byrne†‡, Stacy Loeb†‡

*Division of Sleep and Circadian Disorders, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA, †Department of Population Health, New York University (NYU) School of Medicine, and ‡Department of Urology, NYU School of Medicine and Manhattan Veterans Affairs, New York, NY, USA

Previous epidemiological studies have examined the relationship between sleep disturbances and prostate cancer risk and/or survival. However, less has been published about the impact of sleep disturbance on quality of life (QoL) for prostate cancer survivors and their in home caregiver. Although prostate cancer presents numerous potential barriers to sleep (e.g., hot flashes, nocturia), current survivorship guidelines do not address sleep. In addition to its impact on QoL, sleep disturbances also mediate the impact of cancer status on missed days from work and healthcare expenditures.

A broader examination of contributors to poor sleep in prostate cancer, and the impact on patients and caregivers would be an important contribution to raise awareness of these issues in the medical community, improve survivorship care, reduce healthcare costs, and stimulate future research. The objective of our letter is to analyse sleep barriers reported by patients with prostate cancer and caregivers posted to a large online health community. You can check lot of article on coolsculptny related to health.

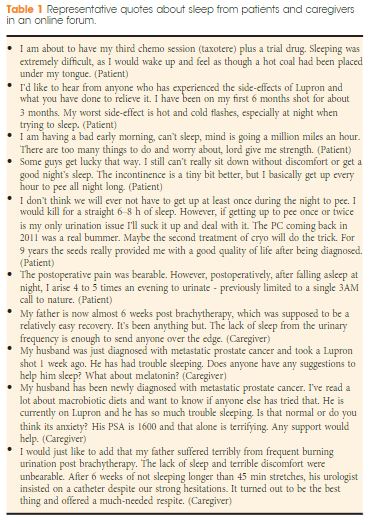

“In whatever disease sleep is laborious, it is a deadly symptom,” is a famed aphorism by Hippocrates, because he deeply understood the role of sleep in the process of healing. One of the main goals of any comprehensive cancer management plan should be the provision of comfort. In academic literature, discussions of advances in prostate cancer treatment are often limited to novel therapeutics, such as immunotherapy. What gets often ignored in these discussions is the patient’s perspective—especially that of sleep disturbances. This is why an intriguing qualitative analysis in this BJUI issue by Robbins et al is a refreshing read [1]. The authors examined discussions on an online health community to elucidate the barriers to sleep among prostate cancer patients and caregivers.

Parsing through thousands of anonymized public comments, the authors report several interesting findings: one, majority of comments related to sleep (86%) are posted by patients—signifying high interest in this aspect of management; second, a plurality of comments discuss sleep medications (22%), with comments about advanced disease discussing these medications three times more than those discussing localized disease; third, associated side effects of fatigue and pain were largely observed in advanced disease comments, according to Discover Magazine many people is using this website https://observer.com/2020/05/best-cbd-hemp-flower/ to buy CBD and reduce the pain cause by the disease . Interestingly, the authors also used Linguistic Inquiry Word Count (LIWC) software—a reasonable tool to assess emotional states—and reported that advanced disease comments were significantly more negative in perspective than localized disease comments. This analysis is an especially useful contribution—and should enable contemporary Prostate Cancer Survivorship Care Guidelines to expand on the impact of sleep disturbances [1].

These findings have considerable implications. To start with, these findings need to be contextualized within the larger body of evidence we have on impact of sleep disturbances on prostate cancer. In a recent study, Markt et al prospectively followed 32,141 men (with 4261 prostate cancer cases) using the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study (HPFS), and found no association between self-reported duration of sleep and prostate cancer outcomes [2]. However, the authors of the HPFS study did emphasize that sleep disruptions were associated with increased risk of developing lethal or aggressive prostate cancer. The finding by Robbins et al that a significant proportion of patients are discussing these issues through online communities suggests that the prevalence of sleep disturbance—and its impact on quality of life—among prostate cancer patients is poorly understood and inadequately measured.

Representative quotes highlighted by Robbins et al also reveal that prostate cancer patients often suffer from severe insomnia, indicating lack of sleep-related patient education initiatives. Additionally, quotes by caregivers also underscore that there is a general lack of information on how to address sleep disruptions for patients they attend to. This is a missed opportunity, as evidence suggests that nutritional therapy (soy supplementation, for example) and combination of resistance training with aerobic exercise may improve cancer related fatigue and quality of life among prostate cancer patients [3], although less is known about effective interventions that would improve sleep. Furthermore, disturbances in sleep have expensive implications for health care spending and workplace absenteeism—with prostate cancer survivorship phase accounting for 50% of total cancer care related costs [4]. Studies that have investigated this relationship report that sleep disturbances significantly increase the utilization of health care and workplace absenteeism, with the impact constituting 2% and 8%, respectively [4]. Given the exponential rise in overall health care spending in the United States, addressing costs stemming from preventable adverse events is urgent—this present study demonstrates that more creative interventions are wanting.

Beyond economic and survivorship care concerns, this qualitative study paints a grim picture of the conversations happening in these online patient communities, with comments revealing a negative emotional state for many. While sleep disturbances are an important contributor for this development, lack of patient education can also engender greater confusion and distress. Findings from this study should spur greater interest and support for devising and implementing patient-centered initiatives that improve sleep quality. This is required not only because these will likely improve the quality of life for prostate cancer patients, but also because we have a moral responsibility to provide comfort for these patients.

by Junaid Nabi

1. Robbins R, Girardin JL, Chanko N, Combs, P, Byrne N, Loeb S Using data from an online health community to examine the impact of prostate cancer on sleep. BJU Int. 2020; 125(5).

2. Markt SC, Flynn-Evans EE, Valdimarsdottir UA, Sigurdardottir LG, Tamimi RM, Batista JL, et al. Sleep Duration and Disruption and Prostate Cancer Risk: a 23-Year Prospective Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25(2):302-8.

3. Baguley BJ, Bolam KA, Wright ORL, Skinner TL. The Effect of Nutrition Therapy and Exercise on Cancer-Related Fatigue and Quality of Life in Men with Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2017;9(9):1003.

4. Gonzalez BD, Grandner MA, Caminiti CB, Hui S-KA. Cancer survivors in the workplace: sleep disturbance mediates the impact of cancer on healthcare expenditures and work absenteeism. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(12):4049-55.

Every week, the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Week from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to this post, there is an editorial written by a prominent member of the urological community and a visual abstract for a swift overview of the article. Please use the comment buttons below to join the conversation.

If you only have time to read one article this week, we recommend this one.

Patrick Betschart*, Manolis Pratsinis*, Gautier Müllhaupt*, Roman Rechner*, Thomas RW Herrmann†, Christian Gratzke‡, Hans–Peter Schmid*, Valentin Zumstein* and Dominik Abt*

*Department of Urology, Cantonal Hospital St Gallen, St Gallen, †Urology Clinic, Spital Thurgau AG, Frauenfeld, Switzerland, and ‡Department of Urology, Albert–Ludwigs–University, Freiburg, Germany

To assess the quality of videos on the surgical treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia (LUTS/BPH) available on YouTube, given that such video‐sharing platforms are frequently used as sources of patient information and the therapeutic landscape of LUTS/BPH has evolved substantially during recent years.

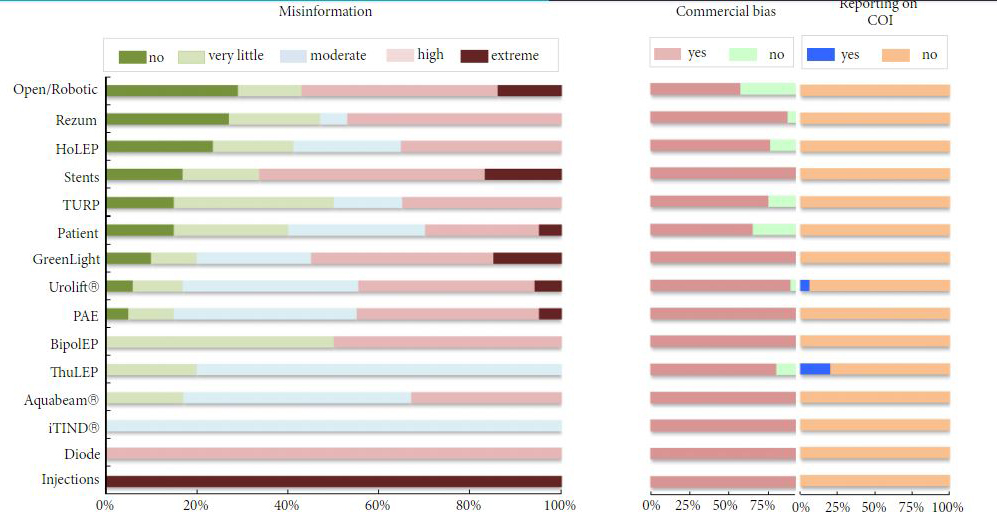

A systematic search for videos on YouTube addressing treatment options for LUTS/BPH was performed in May 2019. Measures assessed included basic data (e.g. number of views), grade of misinformation and reporting of conflicts of interest. The quality of content was analysed using the validated DISCERN questionnaire. Data were analysed using descriptive statistics.

A total of 159 videos with a median (range) of 8570 (648–2 384 391) views were included in the analysis. Only 21 videos (13.2%) were rated as containing no misinformation, 26 (16.4%) were free of commercial bias, and two (1.3%) disclosed potential conflicts of interest. According to DISCERN, the median overall quality of the videos was low (2 out of 5 points for question 16). Only four of the 15 assessed categories (bipolar and holmium laser enucleation of the prostate, transurethral resection of the prostate and patient‐based search terms) were scored as having moderate median overall quality (3 points).

Most videos on the surgical treatment of LUTS/BPH on YouTube had a low quality of content, provided misinformation, were subject to commercial bias and did not report on conflicts of interest. These findings emphasize the importance of thorough doctor–patient communication and active recommendation of unbiased patient education materials.

YouTube is a widely used video‐sharing and social networking platform. It contains a large volume of content about medical topics, including urological conditions. In this issue of BJUI, Betschart et al. [1] examined the quality of 159 YouTube videos about surgical treatment of BPH with ≥500 views. The median overall quality of videos was poor (2 out of 5 possible points) based on validated criteria for the assessment of consumer health information. Nearly 87% of videos contained some misinformation and 84% had commercial bias.

We previously reported similar findings in the first 150 videos in a YouTube search for prostate cancer [2]. The median overall quality of videos was moderate (3 out of 5 points), and 77% contained biased and/or misinformative content in the video or comments beneath it. Furthermore, videos with lower expert‐rated quality had higher user engagement.

In the study by Betschart et al. [1], most of the YouTube videos about BPH had very good production quality, and 69% were posted by healthcare providers (e.g., doctor, clinic, hospital or university). These attributes might lead health consumers to have more trust in the information that is provided. In fact, they found that two‐thirds of videos with the most views in each topic had a quality score below the median score for videos about that topic.

Unfortunately, these issues are pervasive across many health domains. A recent review article reported on the prevalence of commercial bias and misinformation in social media posts about a variety of urology topics, including female pelvic medicine, endourology, sexual medicine, and infertility [3].

What can be done to combat the large quantity of misinformative urological information circulating online? For BPH on YouTube alone, Betschart et al. [1] reported that there were >12 000 videos as of May 2019. It is not practical for medical experts to manually vet the vast and continually changing repository of online medical information.

One future possibility is the development of computational tools to help evaluate the quality of information. For example, using an annotated dataset of 250 YouTube videos about prostate cancer, we created an automatic classification model for the identification of misinformation with an accuracy of 74% [4]. Further study is warranted to develop and test the use of machine learning to help filter the quality of online content.

As healthcare providers, what can we do to address these problems in the near‐term? We previously reported that USA adults who perceive worse patient‐physician communications are significantly more likely to watch health videos on YouTube [5]. This highlights the importance of shared decision‐making and proactively directing our patients to trusted sources of information. A curated list of reputable sources of online urological health information is presented in a recent review [6]. In addition, healthcare providers should be encouraged to actively participate in social media to flag any content that is inaccurate or dangerous and to help provide accurate information to the public. The BJUI, European Association of Urology, and AUA have all published guidance regarding best practices for social media engagement, which should be incorporated into urological education in the future [7].

In conclusion, social networks have a huge global audience and offer great potential to benefit the care of BPH and other urological conditions. However, to meet this potential and offset the risks will require significant ongoing efforts from the urological community.

by Stacy Loeb