Twitter is a great social channel for professionals to exchange ideas. I regularly use Twitter to connect with urologists, health care professionals, patients and thought leaders around the world. I also use Twitter to share my blog posts.

Twitter is a great social channel for professionals to exchange ideas. I regularly use Twitter to connect with urologists, health care professionals, patients and thought leaders around the world. I also use Twitter to share my blog posts.

Participating in Twitter Chats

One of the many other ways I find value on the platform is by participating in Twitter Chats. Twitter chats are a great way to get people with a common interest into a community. A Twitter Chat can be a one-time event; however, most take place on a regular basis – weekly or monthly – and are organized around a designated hashtag.

Weekly healthcare chats that I regularly enjoy include: #hcsmanz (Healthcare and Social Media in Australia and New Zealand) and #hcsm (Healthcare Communications and Social Media) both on Sundays, #hcldr (Healthcare Leader) on Tuesdays, and #HITsm (Health IT Social Media) on Fridays.

My favorite Twitter chat, however, is the monthly #UROJC chat, International Urology Journal Club on Twitter. #UROJC takes place on the first Sunday of every month, starting at 3 pm Eastern time, and continues over a 48-hour period, rather than one hour. During this time, I can review and discuss current research in urology and engage with academic and community urologists around the world. The origins of #UROJC have previously been described by Dr. Henry Woo, @DrHWoo, in a BJUI blog post.

Twitter Chat Tools to Know

When you participate in #UROJC, or any other Twitter Chat, there are a few tools and tips that can be used to enhance your experience.

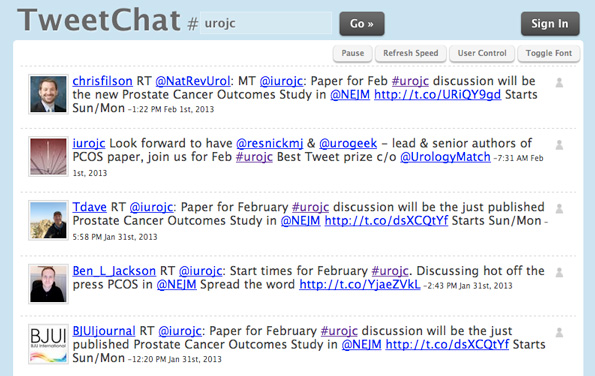

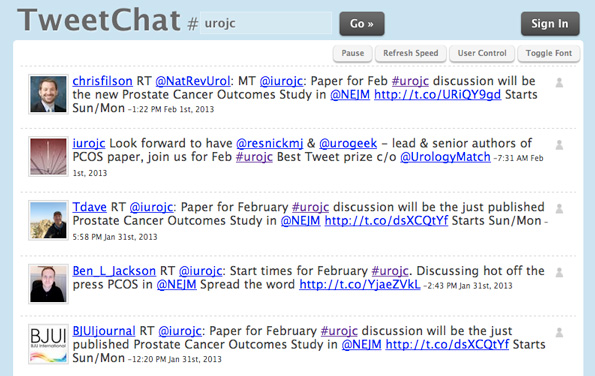

1. Tweetchat

A great application for Twitter Chats and conferences is Tweetchat.com. You can tweet directly from Tweetchat, and your tweets will automatically be appended with the hashtag. All participants using the hashtag can be viewed in a real-time stream.

How to use Tweetchat:

- Go to Tweetchat.com.

- Log in with your Twitter account.

- Add the hashtag for the chat, i.e., #UROJC, in the “room” text box.

- Now you will see all the people participating in the chat displayed in the stream in real time.

- You can tweet directly from the platform through the tweet box provided. Tweetchat.com will automatically add the hashtag, and you are visible in the stream. You can click on buttons next to a tweet to reply or retweet another user.

- You can also click to follow colleagues in the chat via Tweetchat. This is a great way to expand your network.

2. Twitterfall

Twitterfall is similar to Tweetchat, but has some customizable features. For example, you can edit out retweets, and control the speed of the Twitter stream. Twitterfall also has a place to create lists of people you want to engage with.

To get started on Twitterfall:

- Go to Twitterfall.com.

- Log in with your Twitter account to tweet directly from the platform.

- Enter the hashtag #UROJC into the “search” text box.

- View the discussion and participants in the stream.

- Set your selections for a variety of other options including creating a list of participants.

3. Symplur

You can get a transcript of the tweets from each monthly #UROJC chat courtesy of Symplur. This is valuable if you want to review a chat or if you happened to miss a chat altogether.

In addition to chats, Symplur’s Healthcare Hashtag project is a rich resource for discovering and mining healthcare conversations on Twitter around specialties, disease states, patient communities, and healthcare conferences.

It is also interesting, at the end of a chat, to view Symplur’s analytics that show the participants who have the most mentions, tweets and impressions. Symplur can also a great place to identify new people to follow.

4. World Clock:

Because #UROJC is a global discussion over a two-day period, it can be confusing to keep track of starting times across multiple time zones. A great tool to find the time in your part of the world is the World Clock time zone converter.

I hope that you find these Twitter Chat tools and tips helpful, and I look forward to seeing you in the stream of our next monthly #UROJC. You can keep updated on what is up and coming on #UROJC by following the official Twitter account for the chat at @iurojc. You can always connect with me on Twitter @storkbrian.

Comments on this blog are now closed.