Editorial: Incorporating prognostic grade grouping into Gleason grades

The ‘Gleason Grading System’ first proposed by Donald Gleason in 1966 was a revolutionary system for its time. As it advocated the use of a sum score that combined the two most common patterns of prostate cancer seen in a radical prostatectomy specimen to predict the biological outcome of the tumour, rather than the worst pattern that was in common usage with other tumour types, it was truly innovative. Furthermore, although several other classification systems for prostate cancer have been proposed since then, none has stood the test of time as well as the Gleason system and certainly no other system is in widespread use internationally.

Gleason and Mellinger went on to make adjustments and modifications to this classification system in 1974 and 1977, as the series of cases examined was expanded from the original 270 patients to >1000 patients.

Since then, there have been further changes to the Gleason Grading System with the advent of immunocytochemistry and in terms of clarification of the size and spacing of individual acini that are seen in the various patterns originally illustrated by Gleason. A tertiary pattern of prostate cancer, mentioned in passing by Gleason, has also become more clearly identified in a proportion of cases.

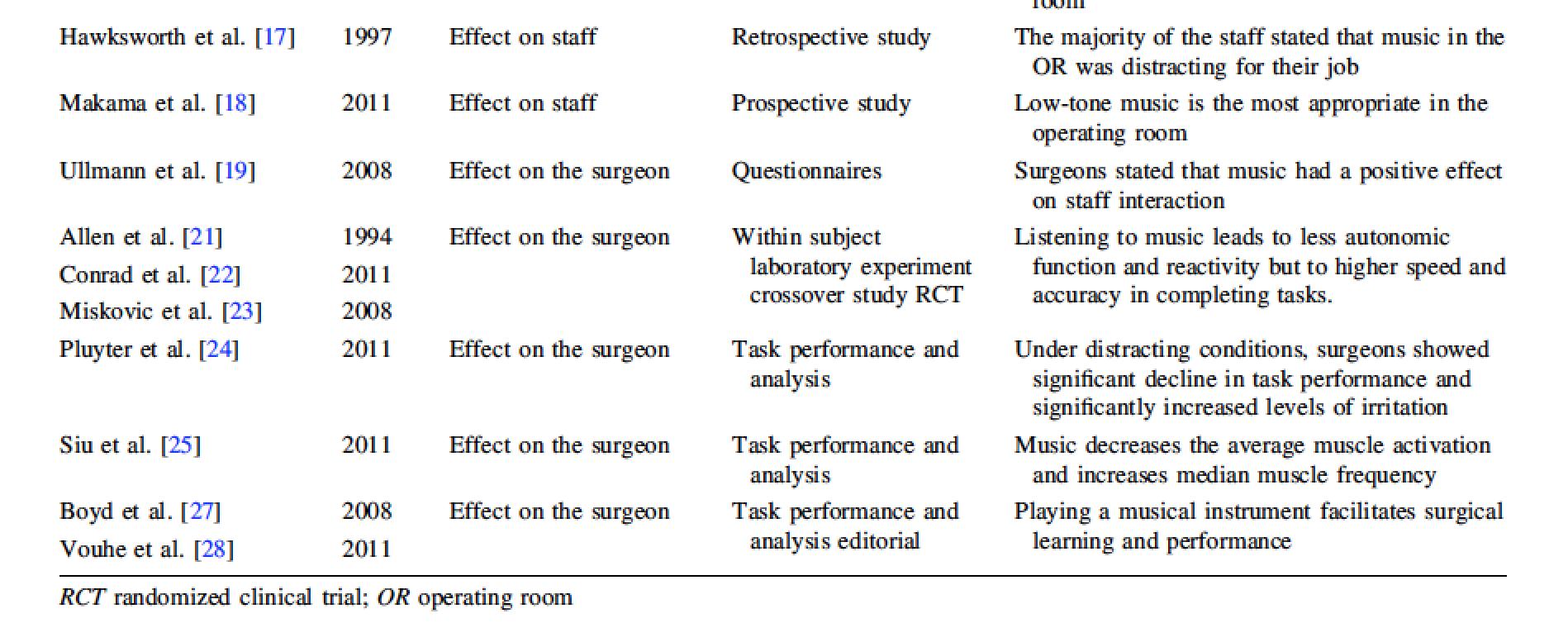

Possibly the most important advance regarding the Gleason Grading System was the result of an International Consensus Conference of Urological Pathologists in 2005. This meeting, comprising >80 specialist pathologists from 20 countries, published the updated or ‘Modified Gleason Grading System’. These guidelines were based on the changes in practice that had taken place in the diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer in the previous 40 years and included evidence for the confirmation that Gleason 1 and 2 patterns should not be assigned on prostatic needle biopsy specimens and that all cribriform areas of tumour were best regarded as Gleason pattern 4 rather than Gleason pattern 3.

Although these modifications have been useful for the surgeon and pathologist, they have not clarified the Gleason grading system for the patient. It is not easy to explain or to understand why a system that in theory could produce a range of Gleason sum scores from 2 to 10, is in practice actually limited on prostatic biopsy to Gleason sum score 6 to 10. Thus, rather confusingly, Gleason 6 is the most favourable category of prostatic carcinoma in terms of prognosis, rather than indicating a ‘middle-of-the-scale’ tumour.

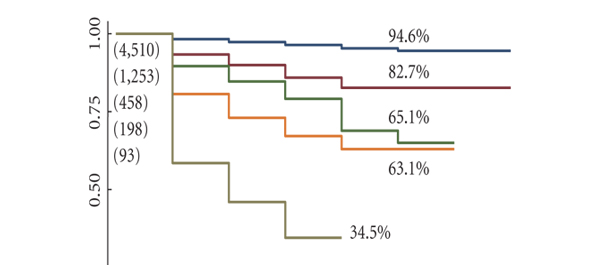

The paper presented in this issue of BJUI, ‘Prognostic Gleason grade grouping: data based on the modified Gleason scoring system’, attempts to compensate for this by allowing the categorisation of prostatic carcinoma not only in terms of Gleason sum score, but also into prognostic groups I to V that correlate with the sum score and may be easier for the patient to appreciate.

This is an important next step in the development of the Gleason Grading System and hopefully one that will be embraced by surgeons and pathologists and more easily accepted by patients.

Alex Freeman

Department of Histopathology, University College London Hospital, London, UK