Is Gleason 6 really cancer?

The recently published Viewpoint of the National Cancer Institute working group on “Overdiagnosis and Overtreatment in Cancer” by Esserman and colleagues [1] raises continued discussion as to whether some lesions currently classified as carcinomas should have the designation of “cancer” removed, based on low rates of progression, death, and other adverse outcomes. Pertinent to those interested in urology, a central example in the article is prostatic adenocarcinoma.

One simple answer to this question is that to a small extent, a subgroup of prostatic lesions has already been reclassified as not cancer: In current practice, needle biopsy or radical prostatectomy specimens with an overall Gleason score (GS) of 5 or less are now quite rare in current practice. This shift is due in part to modern updates to the Gleason grading system [2], under which many tumors now reach thresholds for GS6 or above. However, at least some lesions previously considered adenocarcinoma with a low overall GS would now be categorized as atypical adenomatous hyperplasia or adenosis in the era of immunohistochemistry for markers of prostatic basal cells. Nonetheless, the current and more controversial debate surrounds whether some (or all?) tumors currently classified as GS6 could be recategorized as not “cancer”.

Arguments against removing the cancer designation from some prostatic adenocarcinomas:

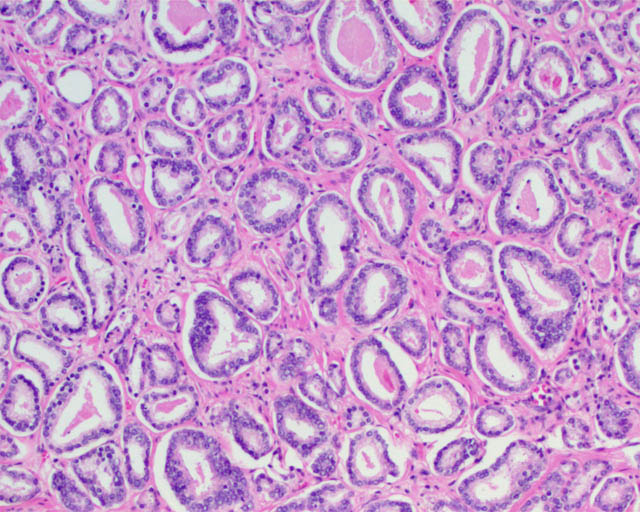

A major difficulty from the pathologic standpoint in adopting a non-cancer nomenclature for some tumors (such as GS6 adenocarcinomas) is that the Gleason pattern 3 component of a GS 3+3=6 tumor (small, round prostatic glands that lack a basal cell layer and infiltrate between benign glands) is for all intents and purposes identical to the Gleason pattern 3 component of a GS 3+4=7 or higher prostate cancer. These similarities are not limited exclusively to the microscopic appearance but also include a number of immunohistochemical and molecular features, as summarized in a recent article addressing this question [3]. Therefore, no pathologic features are as yet defined that ideally predict whether Gleason pattern 3 glands in a biopsy specimen represent a pure GS6 tumor or a component of higher-grade tumor in which the high-grade component is not represented. Not surprisingly, it is not unusual for tumors with GS6 on needle biopsy to be upgraded to GS7 at radical prostatectomy [3], particularly when a high tumor volume is present in the needle biopsy.

Gleason pattern 3 glands from a GS7 tumor, identical to those of a GS6 tumor.

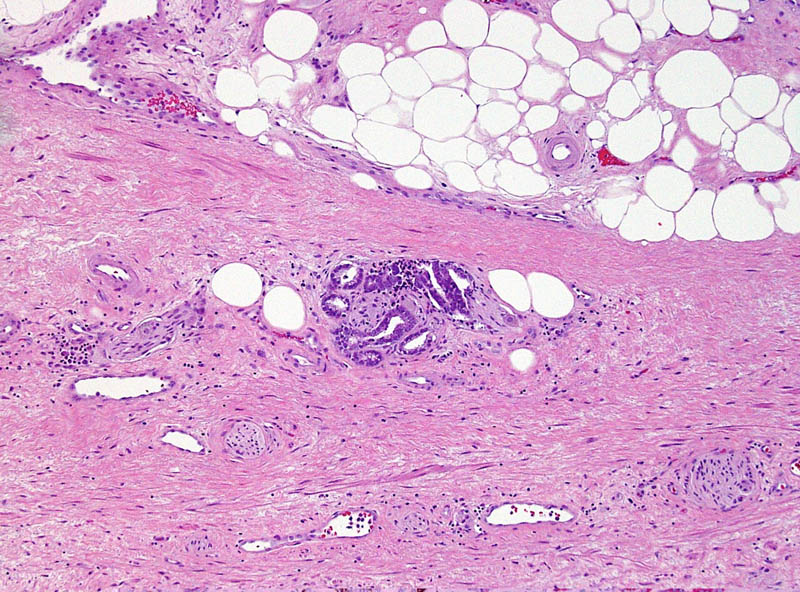

To compare to other cancers with low risk of aggressive behavior, basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma of the skin similarly show locally infiltrative properties, supporting their classification as carcinomas by a classical pathologic definition. Despite that the word “carcinoma” continues to be used for these tumors, most patients are not concerned that they have a life-threatening disease and these lesions are even excluded from the American Cancer Society statistics regarding cancers [4]. In the same way, Gleason pattern 3 glands exhibit infiltrative growth by extending between benign glands, invading nerves, and sometimes extending outside of the prostate. This difference in mindset regarding some types of “cancers” could be considered supportive evidence for the assertion in the recent Melbourne Consensus Statement that uncoupling prostate cancer diagnosis from intervention may be more appropriate than removing its “cancer” nomenclature.

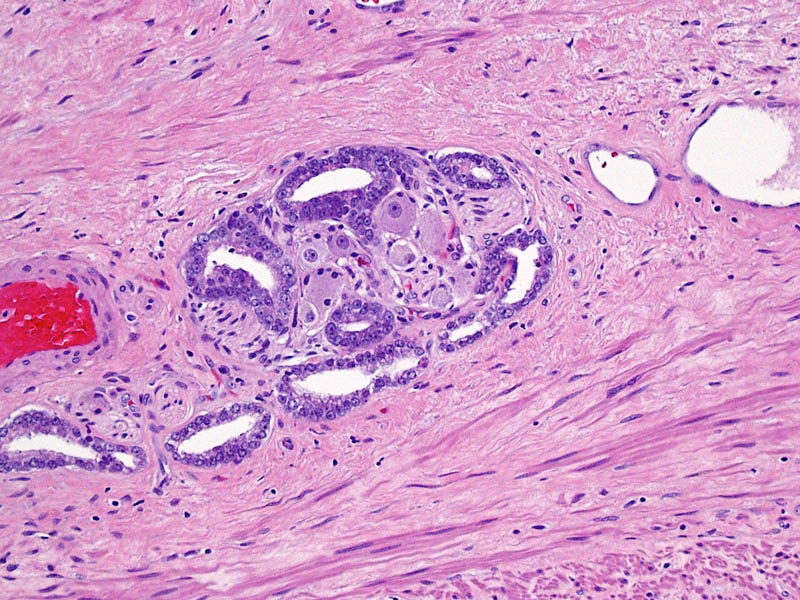

This small GS6 adenocarcinoma was an incidental finding in a radical cystoprostatectomy specimen for bladder cancer but surprisingly extended into periprostatic fat via this focus of perineural invasion.

Supporting removal of the cancer designation from some prostatic adenocarcinomas:

A valid argument of the NCI Viewpoint is that a neoplasm should have a substantive rate of progression and patient death if it is to be considered a cancer. Likewise, others have questioned whether low-volume GS6 tumors fulfill other molecular and pathogenetic hallmarks of cancer, such as unlimited replicative potential and other features [5].

In general, benign and malignant neoplasms can be regarded as having some prototypical gross and microscopic pathologic characteristics, such as a circumscribed vs infiltrative growth and homogeneous vs pleomorphic cell population. However, differentiating benign from malignant lesions also relies heavily on parameters specific to the organ involved. Clear cell renal cell carcinoma, another genitourinary tract tumor, often does not possess these prototypical features of malignancy. Tumors often form a well-circumscribed mass without an “invasive” growth pattern and they often are composed of a uniform population of cells. However, based on known behavior of these tumors, their status as a malignancy is not in doubt. Conversely, renal oncocytoma is a benign neoplasm that shares some of these general features (a round mass composed of a homogeneous population of renal tubular cells). Occasionally oncocytomas appear infiltrative by extending into the perinephric fat or renal vein, yet their status as benign is also not the subject of debate. If some prostate cancers do not have a substantial likelihood of resulting in progression and death, they may not meet an important criterion for a diagnosis of cancer, despite that other features, such as infiltration of tissues, invasion of nerves, and loss of the basal cell layer are characteristic of a malignant neoplasm.

Since a diagnosis of GS6 by needle biopsy is not always predictive of a radical prostatectomy overall GS6, a major challenge to such an approach would be to determine where such a cutoff could be drawn between “cancer” and “not cancer” [5]. If based on tumor volume, it would be difficult to conceptualize that a small amount of GS6 glands would be regarded as a benign lesion, whereas a large amount of identical glands would represent a malignant lesion. Alternatively, the presence of Gleason pattern 4 could used as the point of differentiation (GS7 or above). In the endometrium, a disorganized proliferation of crowded glands with some cytologic features of cancer is regarded as complex atypical hyperplasia. Diagnosis of adenocarcinoma is then reserved for proliferations with a confluent growth of these glands, similar to the threshold for recognizing a component of cribriform glands as Gleason pattern 4. A limitation to such an approach, however, is that a substantial fraction of patients with a needle biopsy GS6 are upgraded to GS7 at radical prostatectomy, as discussed above. Likewise, the ability to treat and monitor GS6 adenocarcinoma nonsurgically is not quite analogous to that of endometrial hyperplasia.

Higher magnification of image 2 shows Gleason pattern 3 glands invading a nerve with ganglion cells.

Other points of discussion

The NCI Viewpoint also suggests that high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (HGPIN) no longer be considered cancer or even neoplasia. A comparison to ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) of the breast for this argument is somewhat flawed, as HGPIN neither contains the word “carcinoma” nor is justification for treatment in and of itself. Its status as a risk factor for a future cancer even remains debated. The proposal to remove “neoplasia” from HGPIN is also a confusing one, particularly as cervical cancer is noted as an example of the successful application of screening, in which “cervical intraepithelial neoplasia” is the preferred term for precancerous lesions. The authors suggest the designation “indolent lesions of epithelial origin” (IDLE) for cancers in this category to convey their low likelihood of aggressive behavior. However, would recognizing the status of these lesions as at least premalignant neoplasms be more appropriate?

Likely a typographical error in the Viewpoint is that the authors also cite reclassification of urothelial papilloma as papillary urothelial neoplasm of low malignant potential [1]. Since urothelial papilloma has never been considered a malignant neoplasm, the authors likely meant reclassifying “grade 1 urothelial carcinoma” to papillary urothelial neoplasm of low malignant potential.

References

[1] Esserman LJ, Thompson IM, Reid B. Overdiagnosis and Overtreatment in Cancer: An Opportunity for Improvement. JAMA. 2013 Jul 29:

[2] Epstein JI, Allsbrook WC, Jr., Amin MB, Egevad LL. The 2005 International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Consensus Conference on Gleason Grading of Prostatic Carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005 Sep: 29:1228-42

[3] Carter HB, Partin AW, Walsh PC, et al. Gleason score 6 adenocarcinoma: should it be labeled as cancer? J Clin Oncol. 2012 Dec 10: 30:4294-6

[4] Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013 Jan: 63:11-30

[5] Ahmed HU, Arya M, Freeman A, Emberton M. Do low-grade and low-volume prostate cancers bear the hallmarks of malignancy? Lancet Oncol. 2012 Nov: 13:e509-17

Sean Williamson is Senior Staff Pathologist in the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Henry Ford Health System, Detroit MI, USA. @Williamson_SR