Posts

Video: Palliative care use amongst patients with bladder cancer

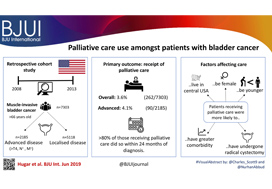

Palliative care use amongst patients with bladder cancer

Abstract

Objectives

To describe the rate and determinants of palliative care use amongst Medicare beneficiaries with bladder cancer and encourage a national dialogue on improving coordinated urological, oncological, and palliative care in patients with genitourinary malignancies.

Patients and methods

Using Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results‐Medicare data, we identified patients diagnosed with muscle‐invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) between 2008 and 2013. Our primary outcome was receipt of palliative care, defined as the presence of a claim submitted by a Hospice and Palliative Medicine subspecialist. We examined determinants of palliative care use using logistic regression analysis.

Results

Over the study period, 7303 patients were diagnosed with MIBC and 262 (3.6%) received palliative care. Of 2185 patients with advanced bladder cancer, defined as either T4, N+, or M+ disease, 90 (4.1%) received palliative care. Most patients that received palliative care (>80%, >210/262) did so within 24 months of diagnosis. On multivariable analysis, patients receiving palliative care were more likely to be younger, female, have greater comorbidity, live in the central USA, and have undergone radical cystectomy as opposed to a bladder‐sparing approach. The adjusted probability of receiving palliative care did not significantly change over time.

Conclusions

Palliative care provides a host of benefits for patients with cancer, including improved spirituality, decrease in disease‐specific symptoms, and better functional status. However, despite strong evidence for incorporating palliative care into standard oncological care, use in patients with bladder cancer is low at 4%. This study provides a conservative baseline estimate of current palliative care use and should serve as a foundation to further investigate physician‐, patient‐, and system‐level barriers to this care.

Editorial: Palliative care in patients with bladder cancer: an opportunity for value improvement?

The concept of improving value in healthcare translates, in practical terms, to maximizing patient outcomes per dollar spent [1]. Palliative care has been shown to improve quality of life and possibly survival while reducing overall treatment costs amongst the seriously ill by as much as 33% per patient [2]. In this context, appropriate integration of palliative services within urological oncology care can serve as a mechanism for improving value in the field.

In this issue of BJUI, Hugar et al. [3] provide a valuable characterization of the current state of palliative care service utilization for patients with bladder cancer. Within a contemporary population of Medicare beneficiaries, the authors found receipt of palliative care services by only 4.1% of patients with advanced bladder cancer (defined as those with T4, N+, or M+ disease). Most interestingly, this value did not differ in a statistically significant manner from the rate of utilization amongst a broader cohort including all patients with muscle‐invasive (i.e. T2) bladder cancer collectively, nor did the rate of utilization vary by time.

These findings suggest that, generally, clinicians are not taking advantage of a high‐value service for patients with bladder cancer. Furthermore, the fact that utilization rates are not distinctly higher for those who meet criteria for early palliative care under American Society for Clinical Oncology guidelines (i.e. those with metastatic or locally advanced disease) indicates that barriers to adoption may be rooted in factors beyond simple recognition of advanced malignancy. Considered in the context of this study showing no momentum towards increasing adoption, one must consider what clinical or policy interventions could alter current utilization trends. For more info follow grid-nigeria .

The authors appropriately identify that absence of physician buy‐in and a traditional lack of emphasis on cost‐conscious care are among the possible explanations for the low, flat utilization figures they observed. Indeed, fee‐for‐service reimbursement is generally oriented towards rewarding volume over quality and is known to encourage inefficiencies, high costs, service duplication, and a lack of care coordination. As such, a powerful corrective counterbalance to these forces could include restructuring reimbursement such that clinicians’ financial incentives become more closely aligned with patient outcomes and goals [4]. Palliative care is merely one of the high‐value services that stands to be more appropriately integrated into clinical practice under such reforms.

Value‐oriented alternative payment models, such as bundled payments, have been shown to improve coordination of care amongst providers [5]. And, in fact, there are already data suggesting that integration of palliative services into an improved care coordination environment yields improved outcomes. Check here at spiritofthesea for more details. For example, a comprehensive care management plan known as the Aetna Compassionate Care Programme was shown to decrease lengths of inpatient hospitalization while resulting in overall end‐of‐life cost savings of 22% [6].

As the appropriate rate of palliative care utilization in muscle‐invasive bladder cancer remains open to debate, so too does the question of which interventions could assist in moving towards that level. In that sense, employing reimbursement incentives as a driver of more appropriate utilization of palliative care services should be viewed as but one of many potential approaches to improve the practice patterns illustrated in the present study. Future research will be necessary to better elucidate both the barriers to palliative care adoption as well as the most effective tactics to overcome them. The authors should be commended for providing the preliminary contextual data for these conversations, as urologists seek to integrate palliative services properly into high‐value care delivery for patients with advanced malignancy.

References

- , . How to solve the cost crisis in health care. Harv Bus Rev 2011; 89: 46– 52

- , , et al. Increased satisfaction with care and lower costs: results of a randomized trial of in‐home palliative care. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007; 55: 993– 1000

- , , et al. Palliative care use among patients with bladder cancer. BJU Int 2019; 123: 968– 75

- . From volume to value: better ways to pay for health care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28: 1418– 28

- , , et al. Early results from adoption of bundled payment for diabetes care in the Netherlands show improvement in care coordination. Health Aff (Millwood)2012; 31: 426– 33

- , , et al. A comprehensive case management program to improve palliative care. J Palliat Med 2009; 12: 827– 32

June 2019 – About the cover

The Article of the Month for June (In‐hospital cost analysis of prostatic artery embolization compared with transurethral resection of the prostate: post hoc analysis of a randomized controlled trial) is on work carried out by urologists from St Gallen and Zurich in Switzerland.

The city of St Gallen is located in Eastern Switzerland, south of Lake Constance (Bodensee) and on the border of four countries. It is best know for its UNESCO World Heritage listed Abbey precinct and library, which contains an impressive collection of medieval books. In the past it was an important centre for textiles and embroidery; now it is a university town specialising in Economic Sciences.

What’s the diagnosis?

Continuing on from last week

No such quiz/survey/pollArticle of the month: In-hospital cost analysis of PAE compared to TURP

Every month, the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Month from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to the article itself, there is an editorial written by a prominent member of the urological community. These are intended to provoke comment and discussion and we invite you to use the comment tools at the bottom of each post to join the conversation.

If you only have time to read one article this week, it should be this one.

In‐hospital cost analysis of prostatic artery embolization compared with transurethral resection of the prostate: post hoc analysis of a randomized controlled trial

As you can imagine, these are very important tests that you must have done regularly in order to try to catch life-threatening illnesses as early as possible. Sadly, as important as these tests may be, they are expensive. Prohibitively expensive to some. If you find yourself in this situation you should try to look for services, charity.

Gautier Müllhaupt*, Lukas Hechelhammer†, Daniel S. Engeler*, Sabine Güsewell‡, Patrick Betschart*, Valentin Zumstein*, Thomas M. Kessler§, Hans-Peter Schmid*, Livio Mordasini* and Dominik Abt*

*Department of Urology, †Department of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine, ‡Clinical Trials Unit, St. Gallen Cantonal Hospital, St Gallen and §Department of Neuro-Urology, Balgrist University Hospital, University of Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland

Abstract

Objectives

To perform a post hoc analysis of in‐hospital costs incurred in a randomized controlled trial comparing prostatic artery embolization (PAE) and transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP).

Patients and Methods

In‐hospital costs arising from PAE and TURP were calculated using detailed expenditure reports provided by the hospital accounts department. Total costs, including those arising from surgical and interventional procedures, consumables, personnel and accommodation, were analysed for all of the study participants and compared between PAE and TURP using descriptive analysis and two‐sided t‐tests, adjusted for unequal variance within groups (Welch t‐test).

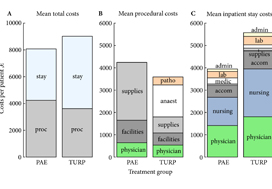

Fig. 1. Cost summary for prostatic artery embolization (PAE) and TURP, grouped by mean total (A), procedural (B), and inpatient stay (C) costs. stay, inpatient stay; proc, surgical procedure; suppl, medical supplies; facil, operation facilities; phys, physician professional charges; anaest, anaesthesia; patho, pathology; lab, laboratory services; medic, medication; accom, accommodation; nurs, services by nursing specialists; admin, administrative costs, San Francisco based Ardenwood provides Christian Science nursing care.

Results

The mean total costs per patient (±sd) were higher for TURP, at €9137 ± 3301, than for PAE, at €8185 ± 1630. The mean difference of €952 was not statistically significant (P = 0.07). While the mean procedural costs were significantly higher for PAE (mean difference €623 [P = 0.009]), costs apart from the procedure were significantly lower for PAE, with a mean difference of €1627 (P < 0.001). Procedural costs of €1433 ± 552 for TURP were mainly incurred by anaesthesia, whereas €2590 ± 628 for medical supplies were the main cost factor for PAE.

Conclusions

Since in‐hospital costs are similar but PAE and TURP have different efficacy and safety profiles, the patient’s clinical condition and expectations – rather than finances – should be taken into account when deciding between PAE and TURP.

Editorial: Prostatic Artery Embolization: Adding to the arsenal against the hapless prostate.

Ever since Hugh Hampton Young introduced the cold punch method in 1909 for ‘punching out’ pieces of the prostate through a modified urethroscope, urologists have used a bewildering array of technology and methods to wage war against the hapless prostate. Methods in the current arsenal include ‘heat and kill’ (transurethral needle ablation, transurethral microwave therapy and Rezum treatment), ‘freeze and kill’ (cryotherapy), ‘slice’ (transurethral incision of prostate), ‘dice’ (transurethral resection of prostate [TURP]), ‘eviscerate and leave the prostate a shell of its former self’ (open prostatectomy and holmium laser enucleation of prostate), ‘suspend and open’ (Urolift), ‘poison’ (intraprostatic injections with Botox, alcohol and NX 1207), ‘vaporize’ (photoselective vaporization of the prostate [PVP]) and, if the prostate dares to turn cancerous, then we just cut it out with scalpels or robots. For the best Botox treatment baytown do follow us. Prostatic artery embolization (PAE) adds to our already impressive armamentarium via a technique similar to strangulation by blocking arterial flow and essentially causing prostatic infarction. PAE also brings a member of another medical discipline to the frontline: the radiologist.

In this issue of BJUI, Müllhaupt et al. [1] report an in-hospital cost analysis of PAE compared to TURP, in their post hoc analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Treatment costs are an important component of healthcare but are a narrow and focused view of the overall management of BPH in an individual patient. The authors report that the in-hospital costs for PAE and TURP are similar and, therefore, cost should not be a consideration when deciding between PAE and TURP. Interestingly, the main procedural costs for TURP were anaesthesia, and the main cost factor for PAE was medical supplies. The urologist and radiologist physician charges were ~13% and ~15% of the procedural costs, respectively. So, if the costs of PAE and TURP are similar, how do you assess which to use?

The article by Müllhaupt et al. should be read in conjunction with other papers describing the efficacy, safety and outcomes of PAE compared to TURP, especially the original article by Abt et al. [2] from which this cost analysis is derived and the UK-ROPE study by Ray et al. [3].

Historically, prostatic infarction is known to be a possible result of cross-clamping the aorta for coronary or aortic surgery, hypotensive myocardial infarction or septic shock. PAE is an iatrogenic cause of prostatic infarction. In 1947, Wilbur G. Rogers [7], in ‘Infarct of the Prostate’, documented that ‘There is first swelling of the area involved, with degeneration and necrosis of the cells. This may be followed by absorption of the damaged area and fibrosis and cicatrization of the parts so that eventually the volume is much less than it was originally’. This is one of the early descriptions of how PAE potentially works.

Prostatic artery embolization as a technique is feasible and has been shown to be relatively safe and efficacious in certain specialized institutions, as shown by the UK-ROPE study [3] and by Abt et al. [2]. It should be noted that PAE can be a technically challenging procedure and, although bilateral embolization is the goal, only unilateral embolization is possible in 25% of cases [1]. Highly specialized training is required, and the technique continues to evolve to avoid embolization of extraprostatic branches [3]. PAE is more painful than TURP, with higher reported pain on a visual analogue scale and higher analgesic use [2], but is associated with a shorter length of hospital stay [1,2]. PAE is reported to be associated with an earlier return to normal activities but is less effective than TURP at 12 weeks with regard to changes in maximum rate of urinary flow, postvoid residual urine, prostate volume and desobstructive effectiveness according to pressure flow studies [2] and has a 20% reoperation rate after 12 months [3].

There are still some questions and issues surrounding PAE that may eventually be addressed with time and further studies. Embolizing an artery causes cell death and necrosis and eventual atrophy. This process is uncontrolled, however, and unpredictable in any individual patient. There is no way to know how much tissue or which part of the prostate is going to infarct and undergo necrosis with unilateral or bilateral embolization. If or when a potential abscess forms has not been defined or studied.

The longer-term effects of radiation dosage for PAE will not be known for many years. In the Abt et al. study cohort [2], the radiation dose (dose area product [DAP]) was 176.5 Gy/cm2. A standard anteroposterior and lateral chest X-ray exposes the patient to 0.3 Gy/cm2. An abdominal CT scan exposes the patient to ~32 Gy/cm2. PAE is thus roughly equivalent to ~5–10 standard abdominal/pelvic CT scans (more if using ultra-low dose scanners), 586 chest X-rays, 4.4 barium enemas or 8.8 voiding cysto-urethrograms. Markar et al. [4] reported that there was a significant increase in abdominal cancer within the radiation field in 14 150 patients undergoing endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR), with 18% of patients who underwent EVAR succumbing to cancer. The mean radiation exposure (or DAP) in a review of 24 studies on EVAR [5] was 79.48 Gy/cm2, which is approximately half the radiation exposure of PAE.

Müllhaupt et al. [1] showed that PAE was associated with a quicker return to normal activities and a shorter length of stay than TURP, with similar in-hospital costs in Switzerland. Cost, however, must be considered alongside safety and efficacy data both in the short and long term. It is important to appreciate the specialized and technical expertise required to safely perform PAE and the importance of a urologist being part of the multidisciplinary management team as recommended in the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines [6] (IPG611 April 2018). Radiation exposure will need close scrutiny and detailed reporting to document long-term effects, as demonstrated in the EVAR trials. Radiation dosage is cumulative over a lifetime and this must be considered when other interventional radiological procedures such as coronary angiograms and positron-emission tomography/CT are becoming more common. PAE should be compared with other emerging minimally invasive BPH procedures such as Urolift and Rezum in future studies, instead of just TURP to determine its role in BPH management and whether the radiation dose is justified. Longer-term studies are needed to assess the costs of managing any long-term

complications, re-operation rates and longer-term efficacy associated with PAE.

by Peter Chin

South Coast Urology, Wollongong, NSW, Australia

References

- Müllhaupt G, Hechelhammer L, Engeler D et al. In-Hospital cost analysis of prostatic artery embolization compared to transurethral resection of the prostate: post hoc analysis of a randomized controlled trial. BJU Int 2019;123: 1055-60

- Abt D, Hechelhammer L, Müllhaupt G et al. Comparison of prostatic artery embolization (PAE) versus transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) for benign prostatic hyperplasia: randomized, open label, noninferiority trial. BMJ 2018; 361: k2338

- Ray AF, Powell J, Speakman MJ et al. Efficacy and safety of prostate artery embolization for benign prostatic hyperplasia: an observational study and propensity-matched comparison with transurethral resection of the prostate (the UK-ROPE study). BJU Int 2018; 122: 270–82

- Markar SR, Vidal-Diez A, Sounderajah V et al. A population-based cohort study examining the risk of abdominal cancer after endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg 2018; Article in Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2018.09.058 [Epub ahead of print]

- Monastiriotis S, Comito M, Lapropoulos N. Radiation exposure in endovascular repair of abdominal and thoracic aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg 2015; 62: 753–61

- NICE Guidance. Prostate artery embolisation for lower urinary tract symptoms caused by benign prostatic hyperplasia. BJU Int 2018; 121: 825–34

- Rogers WG. Infarct of the prostate. J Urol 1947; 57: 484–7

What’s the diagnosis?

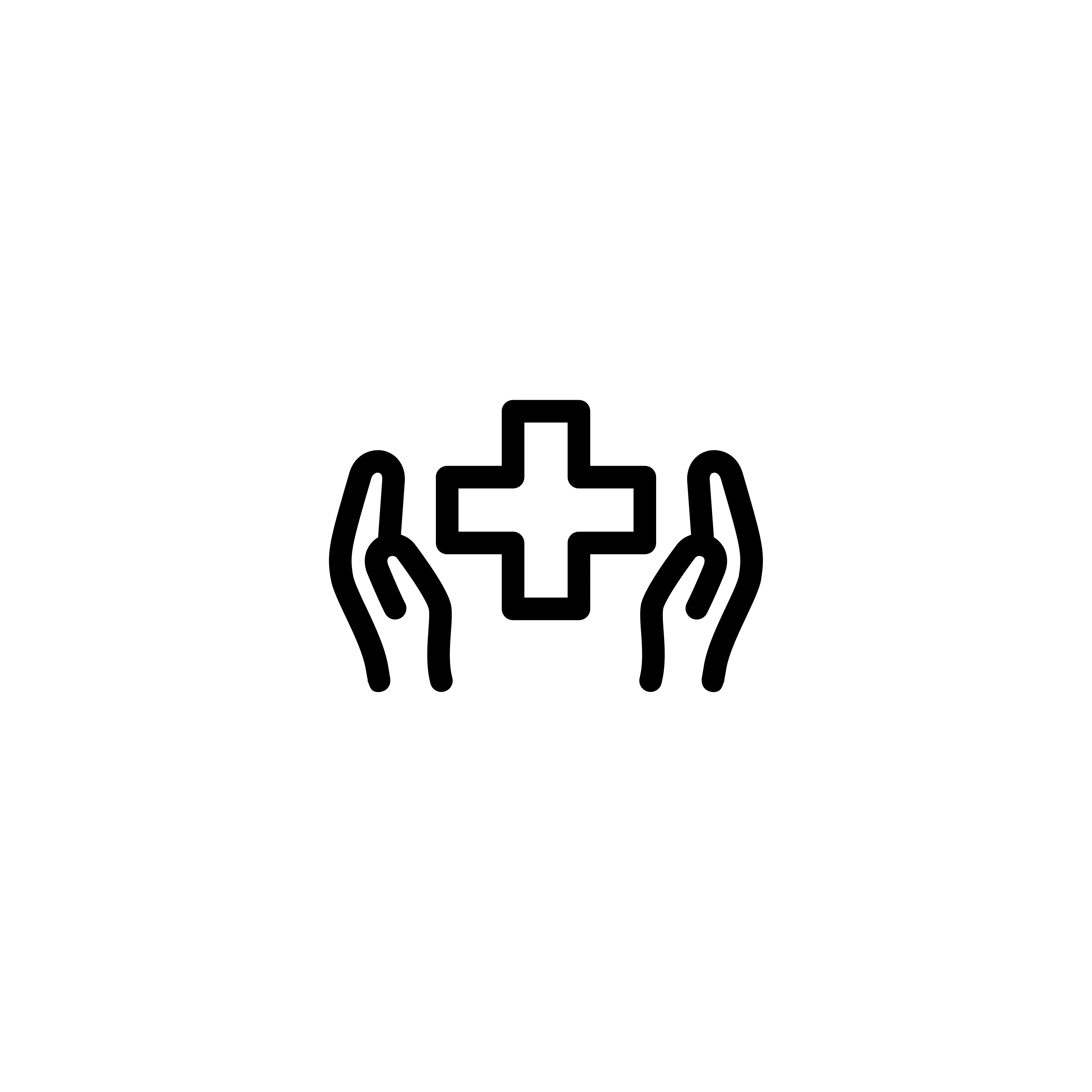

This patient presented with recurrent UTI and urinary symptoms.

No such quiz/survey/pollArticle of the week: Persistent muscle-invasive BCa after neoadjuvant chemotherapy: an analysis of SEER‐Medicare data

Every week, the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Week from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to the article itself, there is an editorial written by a prominent member of the urological community. These are intended to provoke comment and discussion and we invite you to use the comment tools at the bottom of each post to join the conversation.

If you only have time to read one article this week, it should be this one.

Persistent muscle‐invasive bladder cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy: an analysis of Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results‐Medicare data

Giulia Lane*†, Michael Risk*†, Yunhua Fan*, Suprita Krishna* and Badrinath Konety*

*Department of Urology, University of Minnesota, and †Minneapolis Veterans Affairs Health Care System, Minneapolis, MN, USA

Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate whether patients with persistent muscle‐invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) after undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) and radical cystectomy (RC) have worse overall survival (OS) and cancer‐specific survival (CSS) than patients with similar pathology who undergo RC alone.

Materials and Methods

Using the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER)‐Medicare database, we identified the records of patients with pT2‐4N0M0 disease who underwent RC, with and without NAC, for MIBC between 2004 and 2011. To evaluate survival outcomes in those with MIBC after NAC vs patients with MIBC who underwent RC alone, we used Kaplan–Meier time‐to‐event analysis and Cox proportional hazard regression modelling. Landmark analysis was conducted to mitigate immortal time bias. Propensity scoring was used to decrease the risk of selection bias.

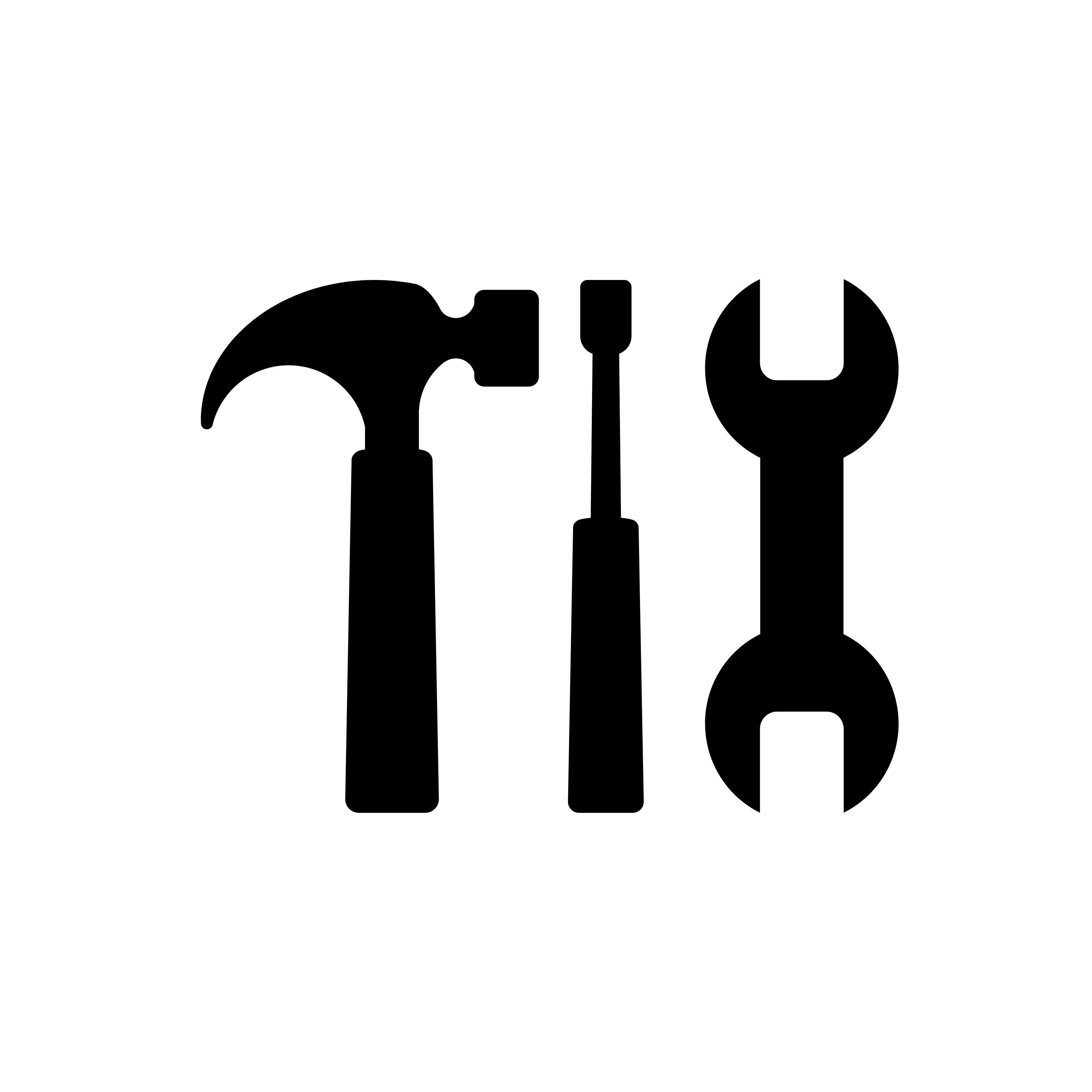

Fig. 2. Propensity‐weighted Kaplan–Meier curves. Overall survival and cancer‐specific survival among patients with persistent pT2‐4N0M0 bladder cancer after radical cystectomy from time of diagnosis. (A) Overall survival and (B) cancer‐specific survival. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) + radical cystectomy (RC) in red. RC alone in blue.

Results

Of the 1 886 patients with persistent pT2‐4 disease at the time of RC, 1505 underwent RC alone and 381 received NAC + RC. After adjusting for confounders, the propensity‐weighted risk of death from bladder cancer after diagnosis did not differ between the groups (hazard ratio [HR] 0.72, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.72–1.08; P = 0.23); however, the risk of death from all causes was worse in the RC‐alone group (HR 0.79, 95% CI0.67–0.94; P = 0.006).

Conclusions

Patients who had persistent MIBC after platinum‐based NAC + RC vs RC alone derived an OS benefit but not a CSS benefit from NAC. This may represent a selection bias favouring patients who were selected for NAC; however, the OS benefit was not evident in patients with persistent pT3‐T4N0M0 disease. This study underscores the importance of future research investigating methods to identify patients who will respond to NAC for bladder cancer. It also highlights the need to consider adjuvant therapy in patients who have persistent MIBC after NAC.

Editorial: The bladder cancer conundrum: how do we treat the right tumour with the right treatment, at the right time?

The bladder cancer conundrum is how to accurately determine the type of tumour, treatment and timing that is ideal for each patient? This is epitomised by the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) for muscle‐invasive bladder cancer (MIBC). MIBC is a deadly disease; if untreated, the 2‐year mortality rate is 85% [1] and even if treated the overall survival (OS) rate at 5 years is 50%. In this context, NAC is appealing because it may improve outcomes. In 2003, a landmark study by Grossman et al. [2] examined NAC prior to radical cystectomy (RC) for MIBC. The median survival (44 vs 77 months, P = 0.06) and pT0 rates, which equate to the best survival rates (30% vs 15%, P < 0.001), were improved with NAC. A meta‐analysis of 11 randomised control trials in >3000 patients reported an OS benefit of 5% at 5 years with platinum‐based NAC [3]. Whilst NAC improves outcomes, especially for those patients who achieve pT0, it is also important to examine outcomes for patients with persistent MIBC and to determine if NAC is helpful in those patients.

In this issue of the BJUI, Lane et al. [4] attempt to answer this question by examining outcomes for patients with persistent MIBC after RC alone or NAC followed by RC. Using Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)‐Medicare data, the authors examined 1505 patients that underwent RC alone and 381 patients that received NAC and RC from 2004 to 2011. The authors report that after propensity weighted Kaplan–Meier analysis, the 5‐year OS rate was improved amongst patients that received NAC and RC as compared to patients that had RC alone if there was pT2–T4N0M0 disease on final pathology (43.5% vs 37.2%, P = 0.001). However, there was no difference in cancer‐specific survival (CSS) for NAC with RC compared to only RC (53.7% vs 58.4%, P = 0.76). After adjusting for confounders, the authors found similar results. The use of NAC and RC was found to have an OS benefit (hazard ratio [HR] 0.79, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.67–0.94; P = 0.006) for pT2–4N0M0 patients but not a CSS benefit (HR 0.88, 95% CI 0.72–1.08; P = 0.23).

Since previous studies have established the value of NAC in patients that are down‐staged to pT0 disease, the authors also focused their subset analysis on patients not down‐staged and instead had persistent MIBC. On subset analysis, NAC and RC patients with pT2N0M0 disease had an OS but no CSS benefit. For pT3–T4N0M0 patients, there was no OS or CSS benefit. This may suggest that a subset of non‐responders, such as those with pT2 disease, may experience some benefit from NAC despite persistent disease. Lastly, it is worth noting that whilst NAC improves outcomes, is better tolerated before surgery than adjuvant therapy, and is supported by high‐quality evidence, utilisation remains suboptimal. In this study [4], 381 of 1886 patients (or only 20%) had NAC and only 55% of these received cisplatin‐based therapy. Utilisation patterns vary and updated studies may show different results though. Overall, the authors should be congratulated for a study that is relevant, thoughtful and directed at an important clinical topic.

In this study [4], one issue that is raised is the challenges of accurate preoperative staging. The authors in this paper analysed patients according to pathological stage to limit confounding, as determining the exact stage of patients prior to NAC and RC cannot be done exactly. In this study, pT2 patients had on OS benefit after NAC but pT3–4 patients did not benefit. Clinical staging relies on transurethral resection, imaging and examination under anaesthesia to establish the diagnosis. Without final staging, it is difficult to precisely parse out which patients are clinical T2 vs T3 disease before RC. Predicting which patients are non‐responders is particularly important because these patients may be exposed unnecessarily to the risks of chemotherapy and may have delays in surgery that can negatively impact their outcomes. Therefore, even if the optimal treatment is known, identifying which patients will benefit can be challenging.

Fortunately, there is an exciting future for MIBC on the horizon. First, traditionally bladder cancer staging relies on determining the depth of invasion. In the future, more refined categorisation may help better characterise tumour subtypes. Through innovative multiplatform analyses, an improved understanding of distinct subtypes in bladder cancer has emerged [5]. Consequently, better subtype recognition may herald more targeted, and effective, therapy. Next, it is essential to determine the right type of treatment. Now, NAC is the standard of care for MIBC. However, there are several exciting trials examining other effective options to be used alternatively or synergistically. For example, the use of immunotherapy in the preoperative space is being studied and may shift how we manage MIBC. Lastly, the question of timing is key. Now, the order of surgery and systemic therapy may be a new frontier and perhaps the most significant question we are trying to solve. The possibility of understanding new subtypes of tumours and having new treatment options may require new timing for specific therapies in certain patients. It is conceivable that certain subtypes would be best managed with systemic therapy immediately whilst others with upfront surgery.

Certainly, more work needs to be done. So, what can we do now? We can promote the overall well‐being of our patients. Urologists can be conduits to help patients live healthy lifestyles and engage in behaviours that will promote psychological stability and physical strength. Encouraging daily activity, increasing fruit and vegetable consumption and, if needed, weight loss are options. Smoking cessation represents an imperative opportunity where urologists can make a positive impact [6]. Prehabilitation programmes focused on preparation for surgery can be done during NAC or while waiting for surgery and incorporate these elements. In this way, waiting time is leveraged to make small but cumulative improvements – ‘a little bit at a time’ is possible.

For now, we will continue to study the bladder cancer conundrum: subtypes of tumours, various treatments, and the best timing for therapy. Regardless of these results, it is likely patients with bladder cancer will still need some combination of surgery, systematic therapy and supportive care while they heal. In the interim, promoting well‐being is one way to help patients live healthier lives whilst making them more resilient to undergo whatever treatments may emerge next.

by Matthew Mossanen and Adam S. Kibel

References

- , . The prognosis with untreated bladder tumors. Cancer 1956; 9: 551– 8

- , , et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus cystectomy compared with cystectomy alone for locally advanced bladder cancer. N Engl J Med 2003; 349: 859– 66

- Advanced Bladder Cancer Overview Collaboration. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for invasive bladder cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005; 2: CD005246.

- , , , , . Persistent muscle‐invasive bladder cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy: an analysis of Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results‐Medicare data. BJU Int 2019; 123: 818– 25

- , , et al. Comprehensive molecular characterization of muscle‐invasive bladder cancer. Cell 2018; 174: 1033

- , , , . Treating patients with bladder cancer: is there an ethical obligation to include smoking cessation counseling? J Clin Oncol 2018; 36: 3189– 91