Article of the Month: Comparing VEILND with OILND for penile cancer

Every Month the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Month from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to the article itself, there are accompanying editorials written by prominent members of the urological community. These blogs are intended to provoke comment and discussion and we invite you to use the comment tools at the bottom of each post to join the conversation.

Finally, the third post under the Article of the Week heading on the homepage will consist of additional material or media. This week we feature a video discussing the paper.

If you only have time to read one article this week, it should be this one.

Prospective study comparing video-endoscopic radical inguinal lymph node dissection (VEILND) with open radical ILND (OILND) for penile cancer over an 8-year period

How to Cite this article:

Kumar, V. and Sethia, K. K. (2017), Prospective study comparing video-endoscopic radical inguinal lymph node dissection (VEILND) with open radical ILND (OILND) for penile cancer over an 8-year period. BJU International, 119: 530–534. doi: 10.1111/bju.13660

Abstract

Objective

To compare the complications and oncological outcomes between video-endoscopic inguinal lymph node dissection (VEILND) and open ILND (OILND) in men with carcinoma of the penis.

Patients and methods

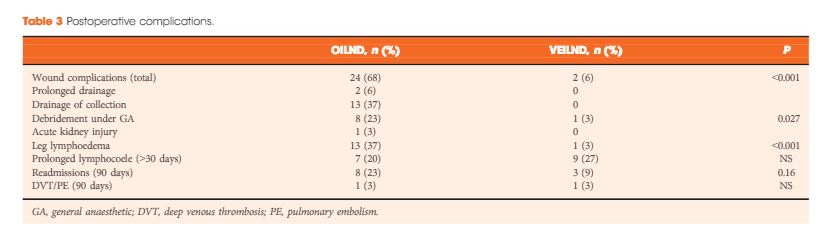

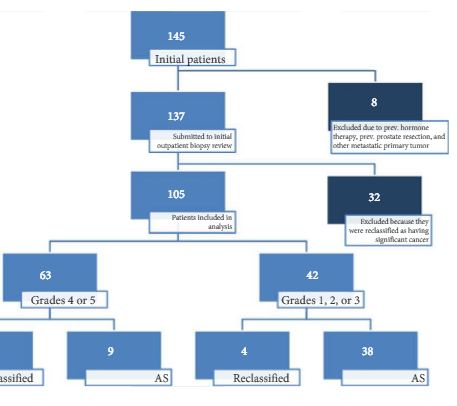

A prospectively collected institutional database was used to determine the outcomes in 42 consecutive patients undergoing ILND between 2008 and 2015 in a centre for treating penile cancer. Before 2013 all procedures were OILNDs. Since 2013 we have performed VEILND on all patients in need of ILND. The wound-related and non-wound-related complications, length of stay, and oncological safety between OILND and VEILND groups were compared. The mean duration of follow-up was 71 months for OILND and 16 months for the VEILND groups.

Results

In the study period 42 patients underwent 68 ILNDs (OILND 35, VEILND 33). The patients’ demographics, primary stage and grade, and indications were comparable in both groups. There were no intraoperative complications in either group. The wound complication rate was significantly lower in the VEILND group at 6% compared to 68% in the OILND group. Lymphocoele rates were similar in both the groups (27% and 20%). The VEILND group had a better or the same lymph node yield, mean number of positive lymph nodes, and lymph node density confirming oncological safety. There were no groin recurrences in either group of patients. VEILND significantly reduced the mean length of stay by 4.8 days (P < 0.001).

Conclusion

VEILND is an oncologically safe procedure with considerably low morbidity and reduced length of stay, at a mean (range) follow-up of 16 (4–35) months.