Article of the Month: MEAL Study – Effects of Diet in PCa Patients on AS

Every Month, the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Month from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to the article itself, there is an accompanying editorial written by a prominent member of the urological community. This blog is intended to provoke comment and discussion and we invite you to use the comment tools at the bottom of each post to join the conversation.

If you only have time to read one article this month, it should be this one.

Men’s Eating and Living (MEAL) study (CALGB 70807 [Alliance]): recruitment feasibility and baseline demographics of a randomized trial of diet in men on active surveillance for prostate cancer

J. Kellogg Parsons*†‡ , John P. Pierce§, James Mohler¶, Electra Paskett**, Sin-Ho Jung††, Michael J. Morris‡‡, Eric Small§§, Olwen Hahn¶¶, Peter Humphrey***, John Taylor††† and James Marshall†††

*Division of Urologic Oncology, UC San Diego Moores Comprehensive Cancer Center, La Jolla, CA, USA, †Department of Urology, UC San Diego Health System, La Jolla, CA, USA, ‡VA San Diego Healthcare System, La Jolla, CA, USA, §Department of Family Medicine and Public Health and Moores Cancer Center, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA, ¶Department of Urology, Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Buffalo, NY, USA, **Department of Medicine, College of Medicine, Comprehensive Cancer Center, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA, ††Alliance Statistics and Data Center, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA, ‡‡Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA, §§UCSF Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center, San Francisco, CA, USA, ¶¶Alliance Central Protocol Operations, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA, ***Department of Pathology, Yale University Medical School, New Haven, CT, USA, and †††Department of Prevention and Population Sciences, Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Buffalo, NY, USA J. Protocol Operations, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA, ***Department of Pathology, Yale University Medical School, New Haven, CT, USA, and †††Department of Prevention and Population Sciences, Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Buffalo, NY, USA

Abstract

Objective

To assess the most recommended books on keto and the feasibility of performing national, randomized trials of dietary interventions for localized prostate cancer.

Methods

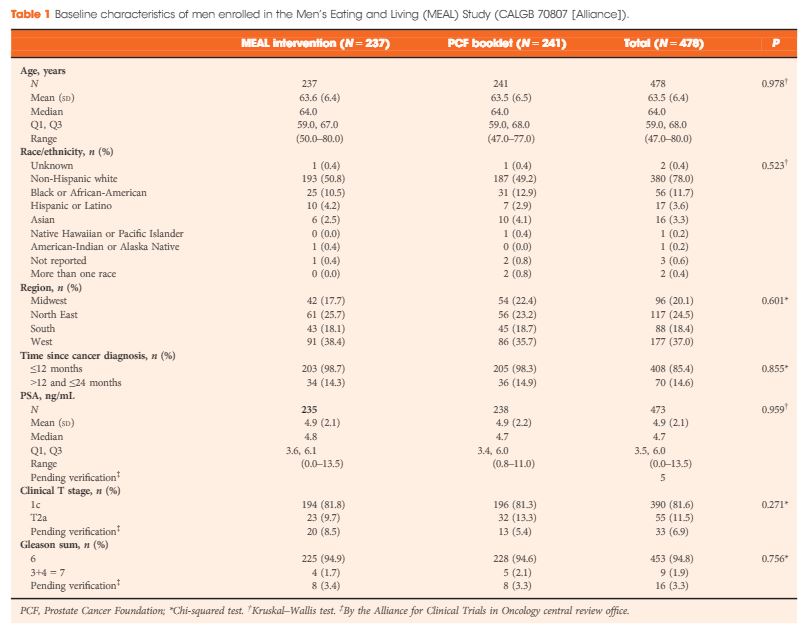

The Men’s Eating and Living (MEAL) study (CALGB 70807 [Alliance]) is a phase III clinical trial testing the efficacy of a high‐vegetable diet to prevent progression in patients with prostate cancer on active surveillance (AS). Participants were randomized to a validated diet counselling intervention or to a control condition. Chi‐squared and Kruskal–Wallis analyses were used to assess between‐group differences at baseline.

Results

Between 2011 and 2015, 478 (103%) of a targeted 464 patients were randomized at 91 study sites. At baseline, the mean (sd) age was 64 (6) years and mean (sd) PSA concentration was 4.9 (2.1) ng/mL. Fifty‐six (12%) participants were African‐American, 17 (4%) were Hispanic/Latino, and 16 (3%) were Asian‐American. There were no significant between‐group differences for age (P = 0.98), race/ethnicity (P = 0.52), geographic region (P = 0.60), time since prostate cancer diagnosis (P = 0.85), PSA concentration (P = 0.96), clinical stage (T1c or T2a; P = 0.27), or Gleason sum (Gleason 6 or 3+4 = 7; P = 0.76). In a pre‐planned analysis, the baseline prostate biopsy samples of the first 50 participants underwent central pathology review to confirm eligibility, with an expectation that <10% would become ineligible. One of 50 participants (2%) became ineligible.

Conclusion

The MEAL study shows the feasibility of implementing national, multi‐institutional phase III clinical trials of diet for prostate cancer and of testing interventions to prevent disease progression in AS.