November 2019 – About the cover

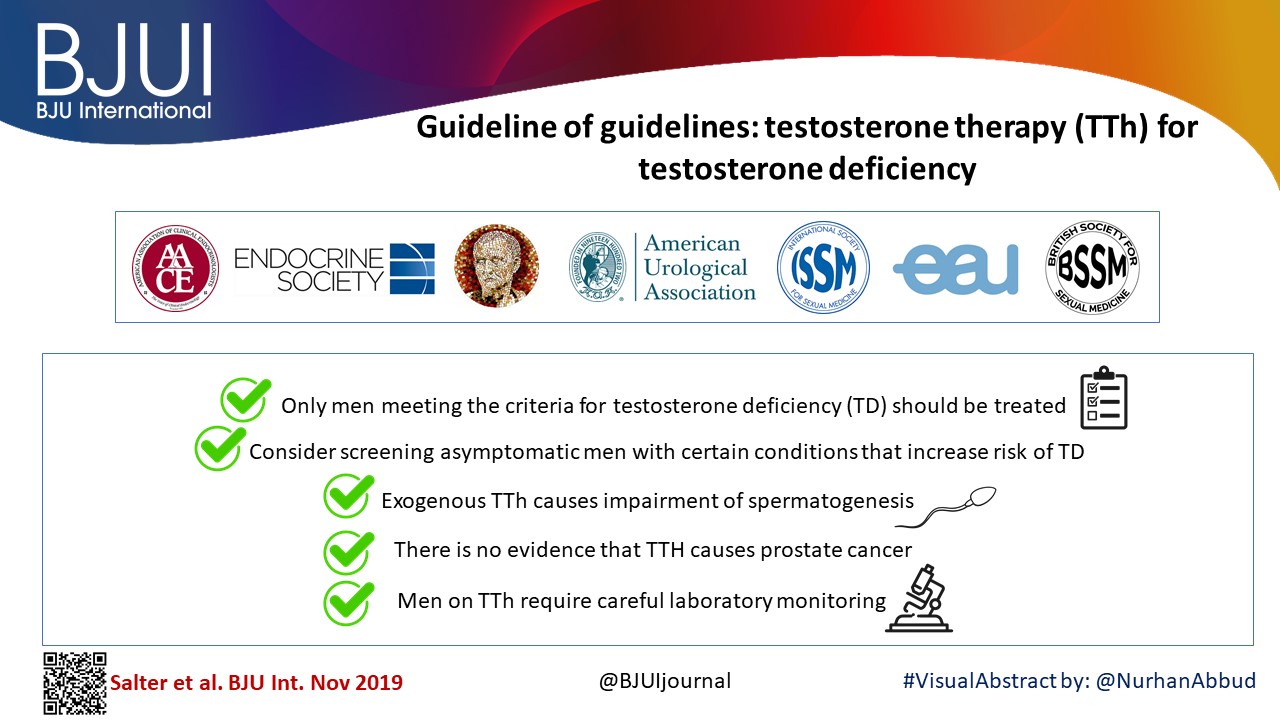

November’s Article of the Month was written by researchers primarily from New York City, USA: Guideline of Guidelines: Testosterone Replacement Therapy for Testosterone Deficiency

The cover image shows the statue of Atlas located within the Rockefeller Center. This “city within a city” was conceived by John D. Rockefeller Jr. and was built during the 1930s, providing valuable jobs during the Great Depression. The first buildings were opened in 1933 providing a center of art, style and entertainment.

The statue of Atlas – a half man/half god giant from Greek mythology – was built in 1937 by Lee Laurie and Rene Paul Chambellan. It is 45 feet (14 metres) tall and weighs 7 tonnes.

Residents’ podcast: NICE guidelines – renal and ureteric stones

Nikita Bhatt is a Specialist Trainee in Urology in the East of England Deanery and a BURST Committee member @BURSTUrology

NICE Guideline – Renal and ureteric stones: assessment and management

Context

Renal and ureteric stones usually present as an acute episode with severe pain, although some stones are picked up incidentally during imaging or may present as a history of infection. The initial diagnosis is made by taking a clinical history and examination and carrying out imaging; initial management is with painkillers and treatment of any infection.

Ongoing treatment of renal and ureteric stones depends on the site of the stone and size of the stone (less than 10 mm, 10 to 20 mm, greater than 20 mm; staghorn stones). Options for treatment range from observation with pain relief to surgical intervention. Open surgery is performed very infrequently; most surgical stone management is minimally invasive and the interventions include shockwave lithotripsy (SWL), ureteroscopy (URS) and percutaneous stone removal (surgery). As well as the site and size of the stone, treatment also depends on local facilities and expertise. Most centres have access to SWL, but many use a mobile machine on a sessional basis rather than a fixed‐site machine, which has easier access during the working week. The use of a mobile machine may affect options for emergency treatment, but may also add to waiting times for non‐emergency treatment.

Although URS for renal and ureteric stones is increasing (there has been a 49% increase from 12,062 treatments in 2009/10, to 18,066 in 2014/15 [Hospital Episode Statistics data]), there is a trend towards day‐case/ambulatory care, with this increasing by 10% to 31,000 cases a year between 2010 and 2015. The total number of bed‐days used for renal stone disease has fallen by 15% since 2009/10. However, waiting times for treatment are increasing and this means that patient satisfaction is likely to be lower.

Because the incidence of renal and ureteric stones and the rate of intervention are increasing, there is a need to reduce recurrences through patient education and lifestyle changes. Assessing dietary factors and changing lifestyle have been shown to reduce the number of episodes in people with renal stone disease.

Adults, children and young people using services, their families and carers, and the public will be able to use the guideline to find out more about what NICE recommends, and help them make decisions. These recommendations apply to all settings in which NHS‐commissioned care is provided.

BJUI Podcasts now available on iTunes, subscribe here https://itunes.apple.com/gb/podcast/bju-international/id1309570262

July 2019 – About the cover

The Article of the Month for July is the latest NICE guideline on prostate cancer – diagnosis and management. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) based in London, UK was established in 1999 to provide national guidance and advice to improve health and social care. It has published over 50 documents covering urology, including guidance, advice and pathways. Since 2012 NICE has also been responsible for social care guidance. Although its main focus is England, NICE has gained an international reputation as a role model for developing clinical guidelines and providing assessments of new technologies.

The cover image shows the UK from space with the northern lights over the horizon. The best place in the UK to see the northern lights is in the northern part of Scotland, however, if the conditions are right they can be seen as far south as Cornwall.

© istock.com/Elen11

Article of the month: NICE Guidance – Prostate cancer: diagnosis and management

Every month, the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Month from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to the article itself, there is an editorial written by a prominent member of the urological community. These are intended to provoke comment and discussion and we invite you to use the comment tools at the bottom of each post to join the conversation.

If you only have time to read one article this month, it should be this one.

NICE Guidance – Prostate cancer: diagnosis and management

Overview

This guideline covers the diagnosis and management of prostate cancer in secondary care, including information on the best way to diagnose and identify different stages of the disease, and how to manage adverse effects of treatment. It also includes recommendations on follow‐up in primary care for people diagnosed with prostate cancer.

Who is it for?

- Healthcare professionals

- Commissioners and providers of prostate cancer services

- People with prostate cancer, their families and carers

Context

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer in men, and the second most common cancer in the UK. In 2014, there were over 46,000 new diagnoses of prostate cancer, which accounts for 13% of all new cancers diagnosed. About 1 in 8 men will get prostate cancer at some point in their life. Prostate cancer can also affect transgender women, as the prostate is usually conserved after gender-confirming surgery, but it is not clear how common it is in this population.

More than 50% of prostate cancer diagnoses in the UK each year are in men aged 70 years and over (2012), and the incidence rate is highest in men aged 90 years and over (2012 to 2014). Out of every 10 prostate cancer cases, 4 are only diagnosed at a late stage in England (2014) and Northern Ireland (2010 to 2014). Incidence rates are projected to rise by 12% between 2014 and 2035 in the UK to 233 cases per 100,000 in 2035.

A total of 84% of men aged 60 to 69 years at diagnosis in 2010/2011 are predicted to survive for 10 or more years after diagnosis. When diagnosed at the earliest stage, virtually all people with prostate cancer survive 5 years or more: this is compared with less than a third of people surviving 5 years or more when diagnosed at the latest stage.

There were approximately 11,000 deaths from prostate cancer in 2014. Mortality rates from prostate cancer are highest in men aged 90 years and over (2012 to 2014). Over the past decade, mortality rates have decreased by more than 13% in the UK. Mortality rates are projected to fall by 16% between 2014 and 2035 to 48 deaths per 100,000 men in 2035.

People of African family origin are at higher risk of prostate cancer (lifetime risk of approximately 1 in 4). Prostate cancer is inversely associated with deprivation, with a higher incidence of cases found in more affluent areas of the UK.

Costs for the inpatient treatment of prostate cancer are predicted to rise to £320.6 million per year in 2020 (from

£276.9 million per year in 2010).

This guidance was updated in 2014 to include several treatments that have been licensed for the management of

hormone-relapsed metastatic prostate cancer since the publication of the original NICE guideline in 2008.

Since the last update in 2014, there have been changes in the way that prostate cancer is diagnosed and treated. Advances in imaging technology, especially multiparametric MRI, have led to changes in practice, and new evidence about some prostate cancer treatments means that some recommendations needed to be updated.

Editorial: NICE guidelines on prostate cancer 2019

The much‐anticipated National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Guidelines are finally published [1] after a period of consultation when they were in the draft phase. These are updated from the previous 2008 and 2014 versions and reflect the changes in our knowledge and practice over the last 10 years. While there are many similarities, the astute reader will find distinct differences from the AUA Guidelines, which feature in a summary booklet released at the #AUA19 meeting in Chicago this spring.

NICE does not comment on screening for prostate cancer so many of us continue to rely on our Guideline of Guidelines [2], which make pragmatic recommendations such as smart screening in well‐informed men who are at higher risk because of their family history. For staging, bone scan has not been replaced by prostate‐specific membrane antigen (PSMA)‐positron‐emission tomography/CT, and Lu‐PSMA theranostics is yet to become an option in castrate‐resistant disease as the international trials are not mature.

Multiparametric MRI before prostate biopsy in men suitable for radical treatment is a new addition, based on the PROMIS [3] and PRECISION trials [1]. This approach is thought to be cost‐effective through reducing the number of biopsies and side effects despite the initial added cost of MRI scanning. In Grade Group 1 and some low‐volume Grade Group 2 cancers, protocol‐based active surveillance is recommended provided the patients are well counselled and it has been discussed by a multidisciplinary team.

To reduce variations in active surveillance, Prostate Cancer UK has carefully examined eight different guidelines and published a consensus statement for the benefit of our patients [4]. We have already promoted this widely on social media and hope that our readers will use this practical tool in their clinics. We often find that some patients just cannot live with a cancer inside their body and seek surgery as a result, however small their tumour. Careful discussion about management options and their risks vs benefits [1] can help patients arrive at a pragmatic decision. The effect of a cancer diagnosis on patients’ minds should therefore not be underestimated and a trained psychologist should be available for appropriate counselling.

NICE also recommends hypofractionated intensity‐modulated radiotherapy, if appropriate, in combination with androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) for localized disease, and methods of decreasing the side effects while increasing accuracy of radiation. As in 2014, robot‐assisted radical prostatectomy remains a surgical option in centres performing at least 150 of these procedures per year [1]. These numbers are similar to those published from other health services such as Canada. One such very high‐volume centre is the Martini Clinic which has reported its comparison of open and robot‐assisted radical prostatectomy in >10 000 patients. The oncological and functional outcomes are no different, open surgery is quicker and there is less blood loss and shorter time to catheter removal after robotic surgery. Just like the randomized trial of the two techniques, this large series highlights that surgeon experience rather than the technique is more important for clinical outcomes [5]. Finally, based on the STAMPEDE results, docetaxel is recommended for metastasis in addition to ADT and can be considered for high‐risk patients receiving ADT and radiotherapy [6]. NICE has also identified a number of important research questions which we hope will be answered by ongoing studies in coming years.

by Prokar Dasgpta, John Davis & Simon Hughes

References

- NICE Guidance. NICE guidelines prostate cancer. BJU Int 2019; 124: 9– 26.

- . Review of prostate cancer screening guidelines. BJU Int 2014; 114: 323– 5

- . The PROMIS of MRI. BJU Int 2016; 118: 7

- , , et al. PCUK consensus statement. BJUI 2019; 124: 47– 54

- , , et al. A comparative study of robot‐assisted and open radical prostatectomy in 10 790 men treated by highly trained surgeons for both procedures. BJU Int 2019; 123: 1031– 40

- , , et al. Taxane‐based chemohormonal therapy for metastatic hormone‐sensitive prostate cancer: a Cochrane Review. BJU Int 2019; [Epub ahead of print]. https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.14711

Residents’ podcast: NICE guidelines bladder cancer

Part of the BURST (@BURSTurology) series of Residents’ podcasts.

Mr Daniel Beder is a BURST Core Surgical Trainee.

Read the article here: NICE guidelines bladder cancer

NICE Stone Guidelines 2019

The NICE (National Institute For Health And Care Excellence) “Renal and ureteric stones: assessment and management” guideline NG118 was published on-line on Tuesday 8th January 2019 and appeared on the BJUI website on Friday 18th January.

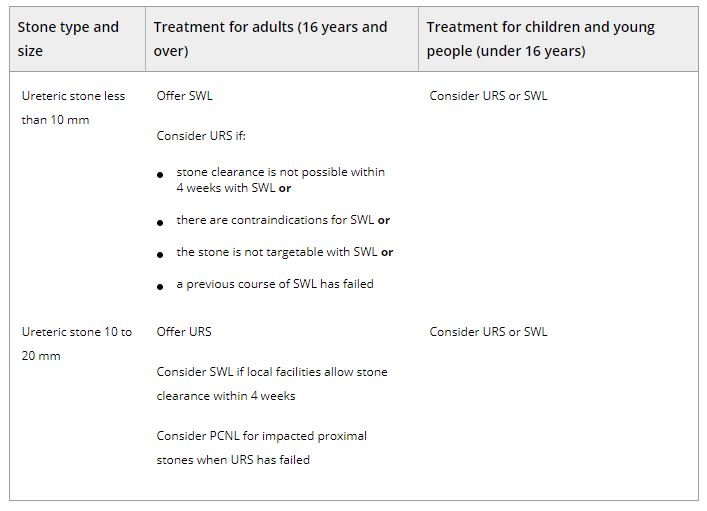

NICE guidelines are based on the best available evidence for the treatment of the specific clinical condition evaluated (i.e. from randomised controlled trials) and aim to provide recommendations that will improve the quality of healthcare within the NHS. As such, the need for a particular guideline is determined by NHS England, and NICE commissions the NGC produce it. The renal and ureteric stone guidelines are comprised a series of evidence reports, each based on the PICO system for a systematic review, covering the breadth of stone management in patients with symptomatic and asymptomatic renal or ureteric stones from initial diagnosis and pain management, through the much debated subject of medical expulsive therapy, to a comprehensive assessment of the surgical treatment of stone disease, including pre- and post- treatment stenting. Follow up imaging, dietary intervention and metabolic investigations have also been reviewed and analysed in detail. These reports are summarised in what is referred to as “The NICE Guideline”, and which is published in the BJUI itself in the February issue (Volume 123, Issue 2, February 2019). The guideline uses the term “offer” to indicate a strong recommendation with the alternative “consider” to indicate a less robust evidence base, with both terms chosen to highlight the need for patient-centred discussion and shared decision making. Indeed, the preface to The Guideline points out the importance of clinical judgment, and that “the individual needs, preferences and values” of patients should be taken into account in decision making, emphasising that “the guideline does not override the responsibility to make decisions appropriate to the circumstances of the individual”.

We have written these blogs to highlight the individual reports, which can be downloaded from NICE at www.nice.org.uk, and to stimulate some thoughts and comments about their implications for the management of stone patients in the UK and internationally.

Daron Smith and Jonathan Glass

Institute of Urology, UCH and Guys and St Thomas’ Hospitals

London, January 15th 2019

Daron Smith Commentary

Considering the patient journey to begin with acute ureteric colic, the first recommendation is that a low-dose non-contrast CT should be performed within 24 hours of presentation (unless a child or pregnant) [Evidence Review B, a 73 page document analysing 5224 screened articles, of which 13 were of sufficient quality to be included in the review]. Their pain management should be with NSAIDs as first line pain relief, i.v. paracetamol as second line and opioids as third line, but antispasmodics should not be used [Evidence Review E, a 227 page document for which 1685 articles were screened, of which 38 were of sufficient quality to be included in the review]. Somewhat contentiously for UK practice, given the SUSPEND findings, is that alpha blockers should be considered for patients with distal ureteric stones less than 10 mm [Evidence Review D, a 424 page document for which 1351 articles were screened, of which 71 were of sufficient quality to be included in the review].

As far as stone interventions are concerned, observation was deemed to be reasonable for asymptomatic stones, especially if less than 5mm, that ESWL should be offered for renal stones less than 10mm and PCNL offered for those greater than 20mm with those in between having all options to be considered. Ureteric stones less than 10mm should be offered ESWL (unless unlikely to be cleared within 4 weeks, or contraindicated, or previously failed) whereas ureteric stones larger than 10mm should be offered URS. These conclusions were drawn from 2459 articles of which 66 were of sufficient quality to be included and summarised [Evidence Review F, a 369 page document]. Perhaps the most important aspect for change in practice relate to the use of stents (both before and after treatment) and the timing of definitive intervention (i.e. without a prior temporising JJ stent). Specifically, the guidance recommends patients with uncontrolled pain, or where the stone is deemed unlikely to pass spontaneously, should have definitive treatment within 48 hours [Evidence Review G, a 39 page document based on 3234 screened articles of which 3 were of sufficient quality to be included in the review]. Stents should not be inserted before ESWL for either renal or ureteric stones [Evidence Review H, a78 page document for which 1630 articles were screened, 7 being sufficiently high quality to be included in the review]. Patients who undergo URS for stones less than 20mm should not have a post-operative stent placed as a matter of routine [Evidence Review I, a 107 page document derived from 1630 screened articles of which 17 were of sufficient quality to be included in the review]. Clearly individual circumstances (ureteric trauma, need for second phase procedure, infection, risk of renal insufficiency) apply to this decision. Given that currently a URS is reimbursed at £2,172, and stent removal as £1,018, perhaps it is time that the treatment episode is remunerated as a combined £3,190, thereby encouraging stent-less procedures instead of stented ones…

Once the treatment is complete, the optimum frequency of follow-up imaging was assessed, comparing monitoring visits less than 6 monthly against 6 monthly and with rapid access/review on request, a strategy that includes no follow up at all for asymptomatic patients [presented in the 29 page Evidence Review J, in which 2385 articles were screened, but none of which were of sufficient quality to be included in the review]. No specific recommendations could therefore be made, other than the need to specifically evaluate the effectiveness of 6 monthly reviews for three years in future research. Of course, if preventative management were more effective, then imaging review would become less important… The guidelines have also reviewed the non-surgical options to avoid stone recurrence [summarised in Evidence Review K – “prevention of recurrence” – a 141 page document in which 3187 articles were screened, of which 19 were of sufficient quality to be included in the review and Evidence Review C, an 81 page document in which 1785 articles were screened, of which 10 were of sufficient quality to be included in the review]. These advised a fluid intake of 2.5 to 3 litres of water per day (with added lemon juice) and that dietary sodium intake should be restricted but calcium intake should not. As far as medical therapy is concerned, potassium citrate and thiazide diuretics should be considered in patients with calcium oxalate stones and hypercalciuria respectively.

In the final aspect of the pathway for stone patients, the clinical and cost effectiveness of metabolic investigations including stone analysis, blood and urine tests (serum calcium and uric acid levels, and urine volume, pH, calcium, oxalate, citrate, sodium, uric acid and cystine) were compared to the outcomes achieved with no metabolic testing following treatment as appropriate for any recurrent stones. Outcomes sought included stone recurrence and need for any intervention, the nature of any metabolic abnormality detected, Quality of life and Adverse events related to the tests or treatment [reported in the 36 page Evidence Review A, in which 933 articles were screened, but which none were of sufficient quality to be reviewed]. A formal research study to evaluate the clinical and cost effectiveness of a full metabolic assessment compared with standard advice alone in people with recurrent calcium oxalate stones was recommended. Following comments in the review process, the guidelines have recommendation that serum calcium should be checked, and biochemical stone analysis considered.

In addition to these individual topic reports, a 49 page evidence review summaries the research methodology and provides an extensive glossary of terms, and a 73 page “Costing analysis of surgical treatments” provides the information regarding the cost effectiveness of the treatments, such as the estimates that 1000 URS procedures and follow up would cost £3,328,895 compared with £961,376 for 1000 ESWL treatments and follow up.

In conclusion, the NICE Guideline Renal and ureteric stones: assessment and management (NG118) is a 33 page summary of over 1700 pages of evidence and analysis. It is therefore an example of where the parts are very much greater than the sum: there is an enormous wealth of high quality data presented in the eleven Evidence Reviews, which are like individual handbooks of contemporary stone management, almost exclusively based on Level 1 Randomised Controlled Trial Evidence. At a time when Brexit dominates national and international news, this is a British Export that we can be proud of.

The real test, of course, will be in the delivery of these ideals, and it is likely that the goal of treating symptomatic patients with ureteric stones within 48 hours will be difficult to achieve. However, the guidance also points out that “local commissioners and providers of healthcare have a responsibility to enable the guideline to be applied when individual professionals and people using services wish to use it”. Along with the GIRFT report, the NICE guidelines are key drivers for change not just in the way that stone patients are managed by their urologist, but in the way that they are treated by the system. Who does not want to be able to treat a patient in pain, with a definitive intervention (be it ESWL or URS) within 48 hours, and without the need for a stent for either the patient or Urologist to worry about. That is the goal that these guidelines have set us; achieving that would be something that Endourologists can be very proud of, and our patients will be extremely grateful for. Are we up for the challenge?

DS

London, January 2019

Jonathan Glass Commentary

The NICE Stone Guidelines – clarification or confusion?

‘This guideline covers assessing and managing renal and ureteric stones.

It aims to improve the detection, clearance and prevention of stones, so reducing

pain and anxiety, and improving quality of life’.

This is the opening paragraph of the recently produced NICE guidelines on the management of urinary tract stones. The guidelines have been produced in the context of existing guidelines produced by the European Association of Urology and the American Urological Association pre-existing, and one hoped that these guidelines would add something for the treatment of stone disease in the UK to justify the expenditure spent producing them. I write these comments in full recognition of the terms of reference to which NICE adheres in producing a set of guidelines.

I, with other members of the committee of the Section of Endourology of BAUS wrote a response to the draft guidelines and we are delighted that the committee has changed some aspects of the published guidelines as a result of our (and other contributions) to the consultation process. I must record however that what follows is a personal opinion, and not that of the committee.

These guidelines do refer to patients with a single stone. That of course immediately means that they have limited application to many of our patients who have multiple stones at first presentation.

The draft guidelines, which are in the public domain, stated ‘Do not use opioids’ in the treatment of ureteric colic. Although this has been changed to ‘Do not offer opioids to adults, children and young people with suspected renal colic unless both NSAIDs and intravenous paracetamol are contraindicated or have not been effective’ this still potentially leaves patient in severe pain for too long. Our first duty as doctors is to relieve pain. In my view, as a doctor caring for stone patients but also as an individual who has suffered ureteric colic, if opioids are needed, they should be given in a timely manner.

The recommendations on medical expulsive therapy are unusual at best and arguably a little bizarre and confusing to the British urologist. There is good evidence from a large UK study – the SUSPEND trial – that alpha blockers have little role to play in improving stone passage. This is the best level 1 evidence in the use of alpha blockers in stone disease. The study was sponsored by the NIHR and as such was truly independent, was statistically robust, and randomised. A representation was made to the guidelines committee by the Aberdeen group that published the study following distribution of the draft guidelines pointing out the robust nature of their study and the less than robust nature of the studies that made up the meta-analysis from which the guideline was derived. I would suggest that this guideline puts British urologists in a situation of huge uncertainty about how we advise our patients in this regard. Do we tell our patients the best evidence shows one course of action – not to use alpha blockers, but the NICE guidelines suggest another path? (I am pleased however that the administration of nifedipine, the use of which appeared in the draft guidelines, was removed from the final document).

The recommendation about pre-stenting children with staghorn stones prior to lithotripsy is arguably an historical perspective. Children with staghorn stones should be considered for primary percutaneous surgery. The recommendation in the guideline possibly reflects review of papers in a field where treatments and approaches to care have changed considerably in the last 10 years. I recognise that robust level 1A evidence is lacking for these interventions. It could indeed be argued that a guideline stating ‘consider ESWL, ureteroscopy or PCNL’ for stones 10-20mm and for stones greater than 20mm or staghorn stones is of limited use. Complex patients require bespoke care individualised to the patient in front of the clinician, taking in to account the stone and all other factors with respect to the patient other than the stone.

Suggesting treatment within 48 hours of presentation of patients with ureteric stones including lithotripsy will put urologists under huge pressure. Patients could hold up these guidelines and demand care. Treatment within 48 hours is often unnecessary, has huge cost implications, may well be unachievable and could lead to excessive intervention. To introduce it successfully, given that most stones present to district general hospitals, would suggest that NICE is calling for a lithotripter in every DGH, and in so doing, suggests the death of the mobile lithotripsy service; alternatively it will require the rapid and streamlined transfer of patients to stone centres for intervention. Either way the cost implications of this are considerable. I am certainly an advocate for the clinically appropriate timely treatment of stone patients but producing guidelines that are possibly unrealistic and impossible to implement might be considered a missed opportunity.

The recommendation to not offer routine stenting to patients undergoing ureteroscopy is controversial. As clinicians we understand the symptoms caused by stents. We also know the risk of sepsis following any stone intervention, the pain from stones obstructing the ureter and the oedema generated by ureteroscopy in the unstented ureter. Sepsis from urological disease is life threatening. These guidelines allow the legal justification of leaving a ureter unstented post ureteroscopy. I don’t know and can’t always predict which patients are going to go septic post intervention. Stents in this scenario save lives but proving that with level 1A evidence is nigh on impossible. I have concerns that this recommendation is potentially harmful and may be dangerous. We accept that many patients have interventions and procedures that may appear unnecessary to protect the few where it is life saving. This is true of nasogastric tubes following major surgery, of patients having a radical prostatectomy, of the placement of the nephrostomy tube following percutaneous surgery. It is also true of stents after ureteroscopy.

The metabolic considerations are a little odd. Sending the stone for analysis is only something that should be considered in these guidelines, and yet recommendations are made – based on the stone analysis. Similarly, there are no recommendations for metabolic testing beyond taking a serum calcium, and yet treatments are recommended for patients with hypocitraturia or hypercalciuria with no suggestion when and in whom these conditions should be sought and diagnosed.

Is this an opportunity lost? Do these recommendations justify the considerable cost in time and money that NICE has put in? Are these guidelines potentially harmful – and will they result in the justification of stones not being sent for analysis, the inappropriate use of alpha blockers, obstructed infected kidneys after ureteroscopy and a serum creatinine never being sent.

I have a healthy scepticism for medicine by committee. The MDT discusses treatments for prostate cancer and makes recommendations without the patient being present. I am not sure this process has relieved me of my scepticism. ‘This guideline… aims to improve the detection, clearance and prevention of stones, so reducing pain and anxiety, and improving quality of life’. Read them, and decide for yourselves whether these aims have been met and the expense producing them justified.

JG

London, January 2019

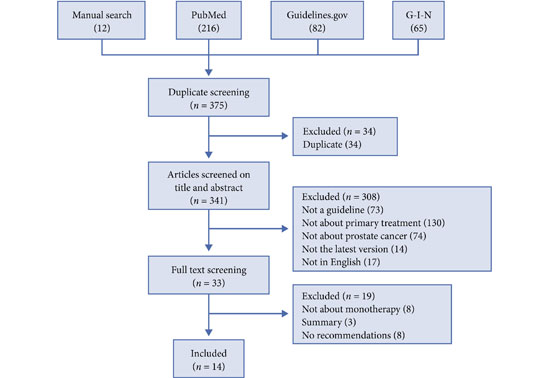

Guideline of guidelines: primary monotherapies for localised or locally advanced prostate cancer

Abstract:

Decisions regarding the primary treatment of prostate cancer depend on several patient‐ and disease‐specific factors. Several international guidelines regarding the primary treatment of prostate cancer exist; however, they have not been formally compared. As guidelines often contradict each other, we aimed to systematically compare recommendations regarding the different primary treatment modalities of prostate cancer between guidelines. We searched Medline, the National Guidelines Clearinghouse, the library of the Guidelines International Network, and the websites of major urological associations for prostate cancer treatment guidelines. In total, 14 guidelines from 12 organisations were included in the present article. One of the main discrepancies concerned the definition of ‘localised’ prostate cancer. Localised prostate cancer was defined as cT1–cT3 in most guidelines; however, this disease stage was defined in other guidelines as cT1–cT2, or as any T‐stage as long as there is no lymph node involvement (N0) or metastases (M0). In addition, the risk stratification of localised cancer differed considerably between guidelines. Recommendations regarding radical prostatectomy and hormonal therapy were largely consistent between the guidelines. However, recommendations regarding active surveillance, brachytherapy, and external beam radiotherapy varied, mainly as a result of the inconsistencies in the risk stratification. The differences in year of publication and the methodology (i.e. consensus‐based or evidence‐based) for developing the guidelines might partly explain the differences in recommendations. It can be assumed that the observed variation in international clinical practice regarding the primary treatment of prostate cancer might be partly due to the inconsistent recommendations in different guidelines.

Michelle Lancee, Kari A.O. Tikkinen, Theo M. de Reijke, Vesa V. Kataja, Katja K.H. Aben and Robin W.M. Vernooij

Article of the Week: NICE Advice – Prolaris Gene Expression Assay

Every Week, the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Week from the current issue of BJUI. The summary is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

If you only have time to read one article this week, it should be this one.

NICE Advice – Prolaris gene expression assay for assessing long‐term risk of prostate cancer progression