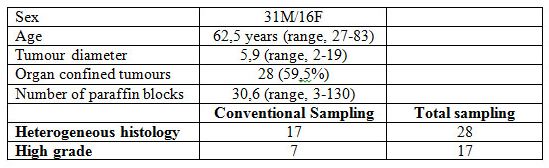

Primary Follicular Lymphoma of the Bladder: A Case Report and Review of the Literature

Primary non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the bladder (PNHLB) is extremely rare with only 110 cases identified in the medical literature.

Authors: Roberts, Samuel; Nagonkar, Santoshi; Zardawi, Ibrahim M.

Manning Rural Referral Hospital, Taree, NSW, Australia

Corresponding Author: Dr Samuel Roberts 84 Scenic Drive, Merewether, NSW 2291 Australia samuel.roberts@hnehealth.nsw.gov.au

Introduction

Primary non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the bladder (PNHLB) is extremely rare with only 110 cases identified in the medical literature [1,2]. The disease has a median age distribution of 64–69 years and shows a female preponderance with a female to male ratio of 2.7:1 [3–5]. Chronic inflammation has been suggested as a possible aetiological factor and a history of chronic cystitis has been documented in over 20% of patients [4–6]. We describe a case of PNHLB and review the literature.

Case Report

A 42-year-old, healthy mother of two presented with a 4 month history of haematuria and dysuria. Antibiotic management offered by her general practitioner initially resolved the symptoms but they later recurred. A pelvic ultrasound revealed an 8 cm mass arising from the bladder base. She had lost approximately 6 kg over 6 months and also complained of lethargy, although there was no history of night sweats or fever. There was also no history of chronic cystitis. She worked as a childcare worker and denied smoking or drinking alcohol; though she was exposed to passive smoking during childhood. She gave a family history of bowel cancer. Her initial examination revealed tenderness and a vague mass in the supra-pubic region, but was otherwise unremarkable.

Investigations

Preliminary blood results were within normal limits, apart from mild iron deficiency anaemia.

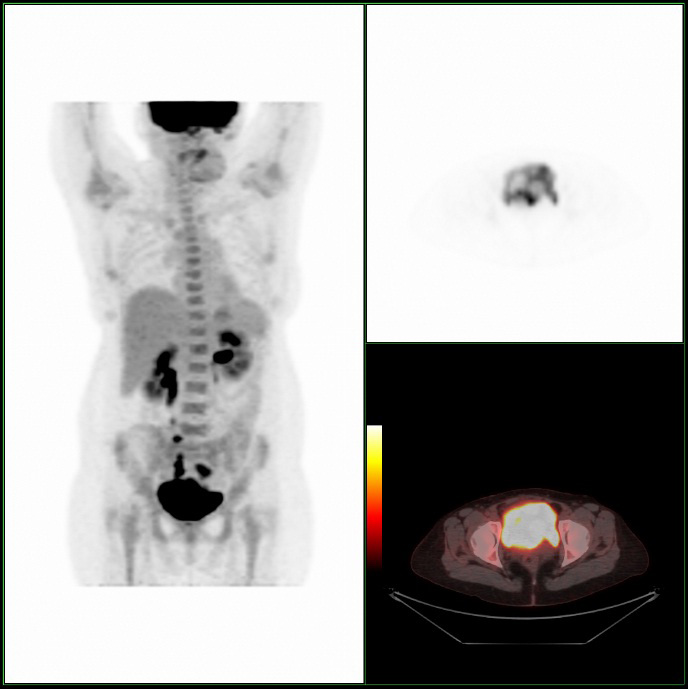

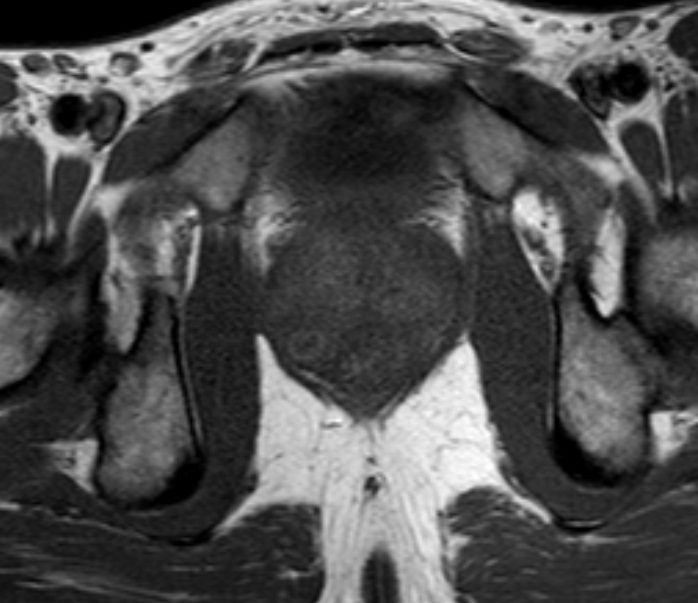

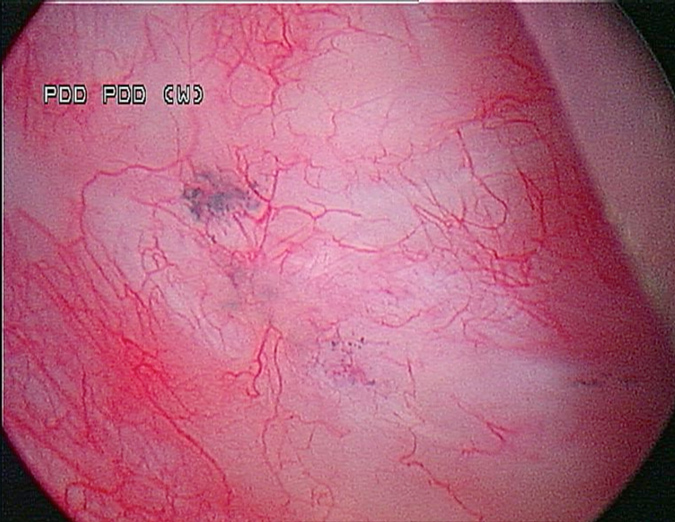

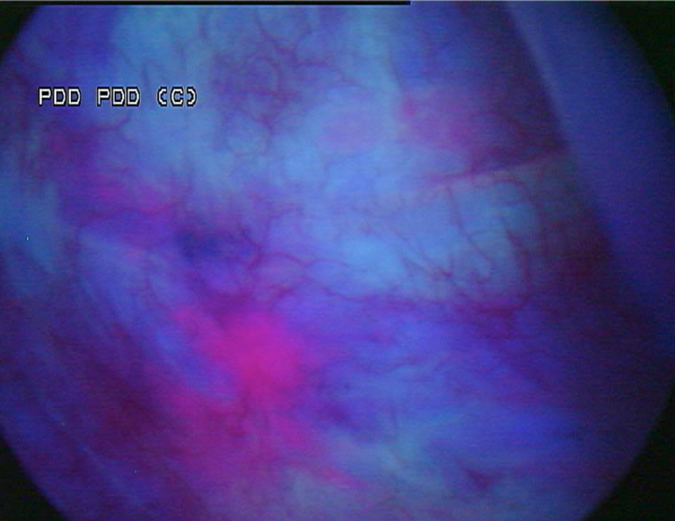

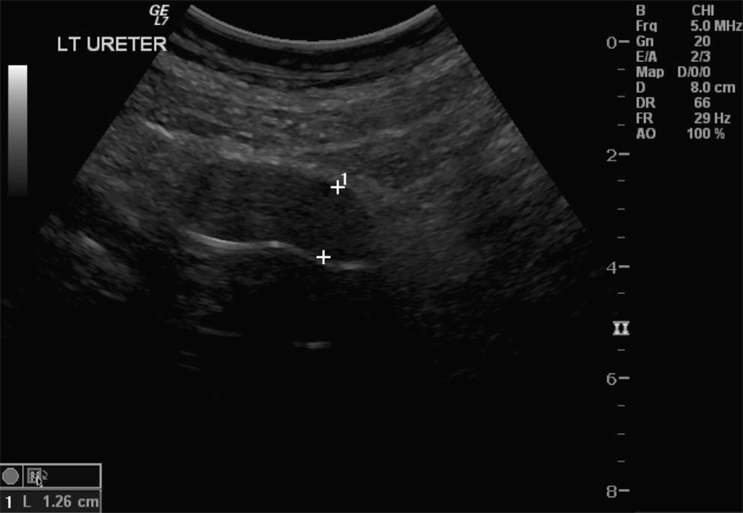

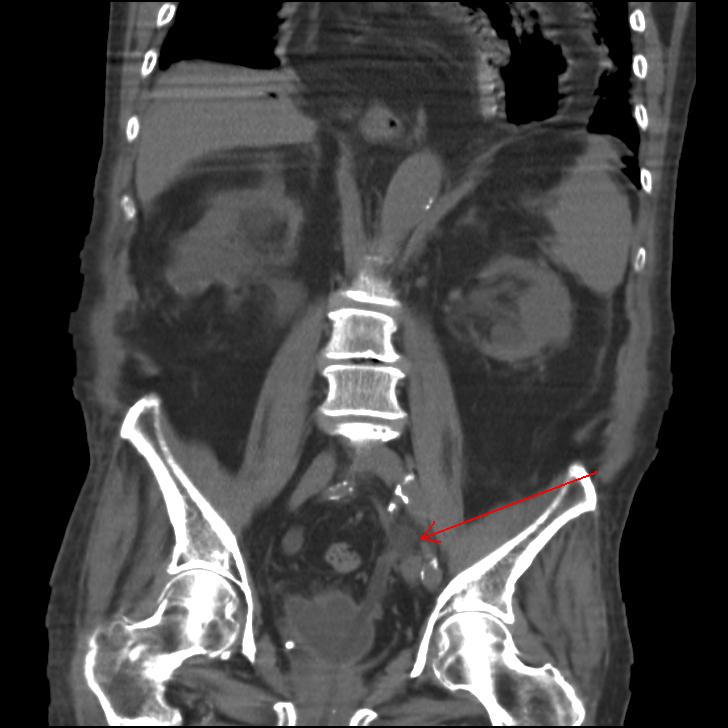

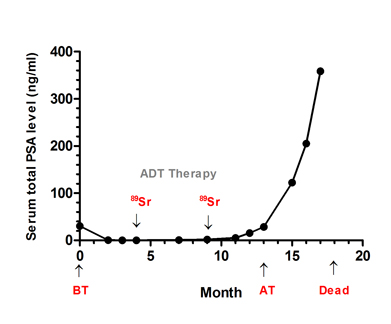

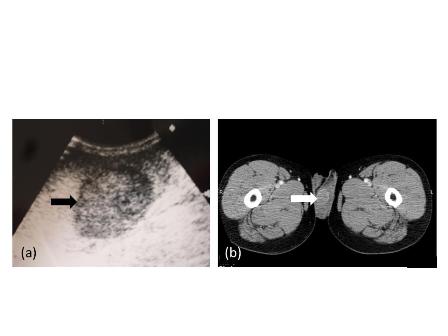

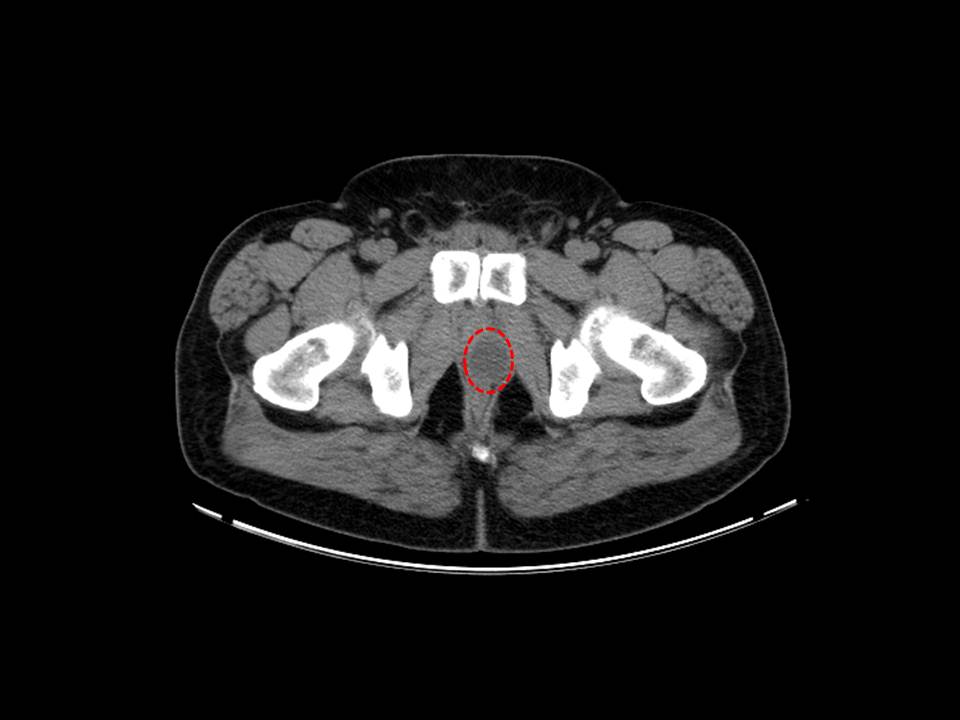

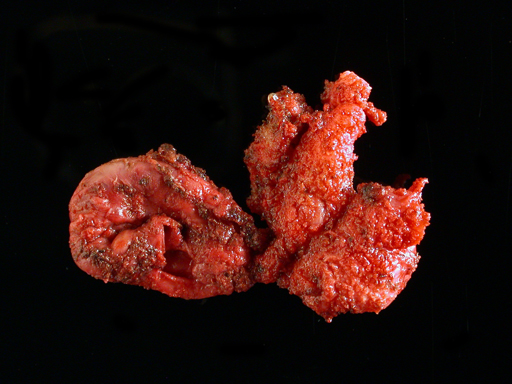

A Cystoscopy revealed a large solid tumour occupying the entire right lateral and posterior walls of the bladder. Loop resection was attempted but abandoned part way through due to the very large size of the tumour. A post-cystoscopy staging contrast enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan confirmed a 12 x 8.5 x 9 cm mass, with an aortocaval lymph node at the upper size limit of normal. Positron emission tomography (PET) scan showed no radiolabelled glucose uptake in this node and did not identify any disease outside the bladder. The bladder mass showed less uptake than adjacent urine but increased uptake in comparison with background (Fig 1).

Pathology

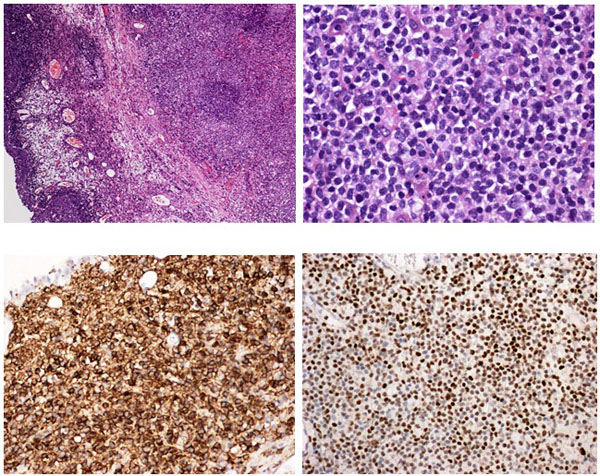

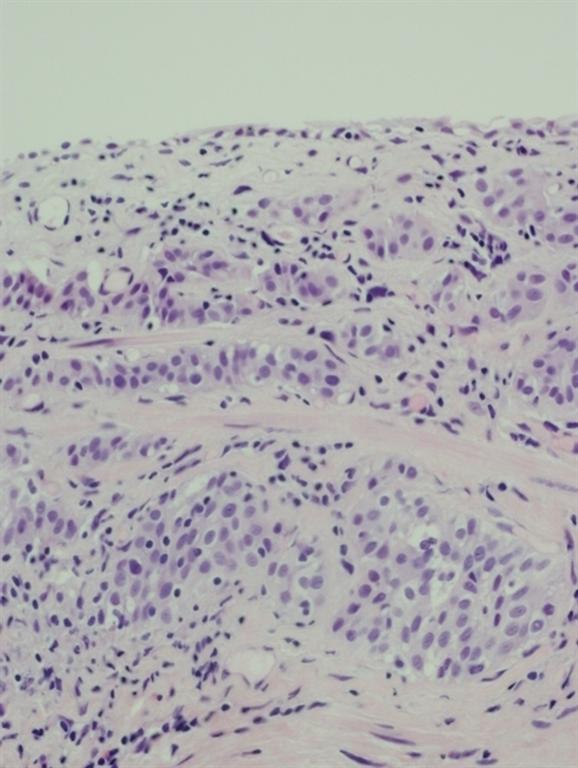

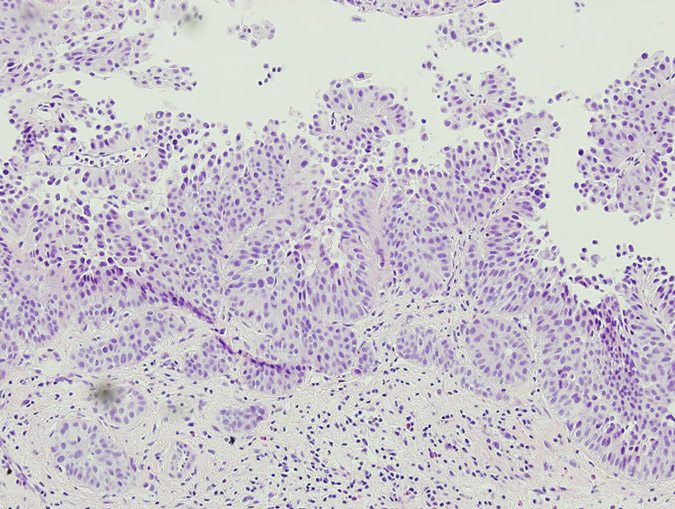

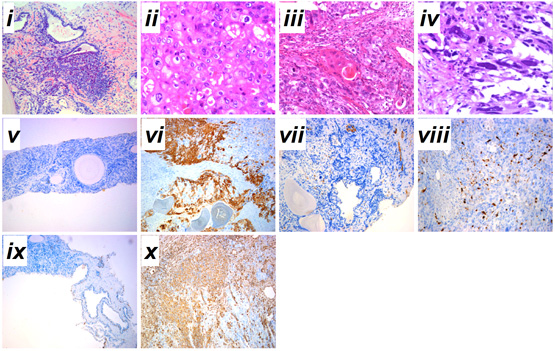

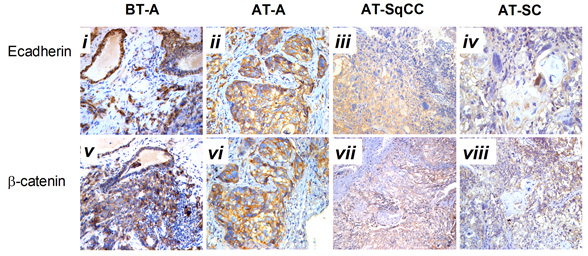

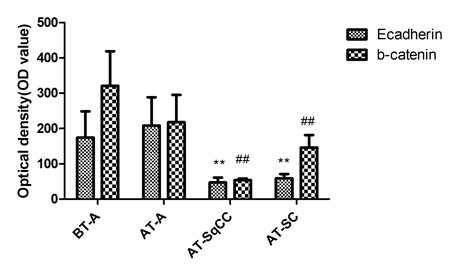

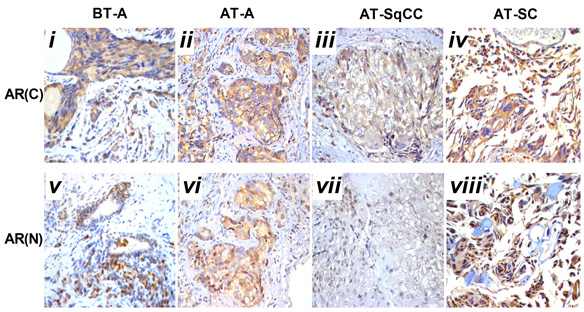

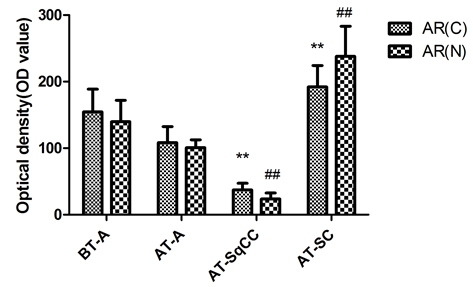

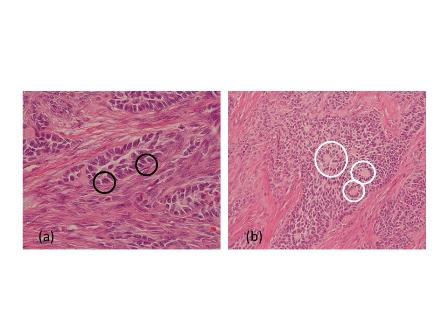

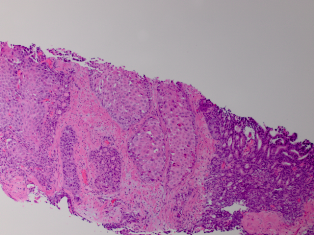

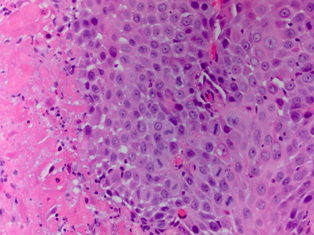

Pathology revealed a WHO grade 2 follicle centre cell lymphoma expressing CD20, CD10, BCL-2 and BCL-6 (Fig 2). CD5 and CD23 were negative.

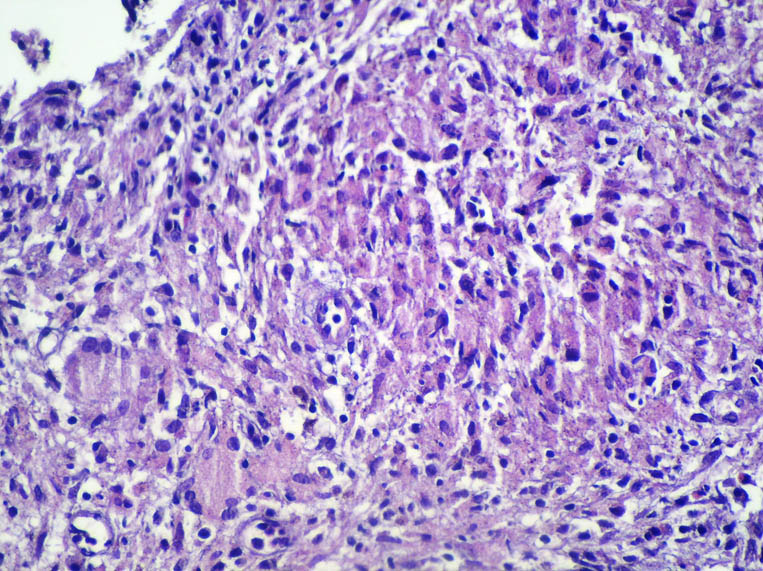

Management

The patient received five cycles of cyclophosphamide, doxorubacin, vincristine, prednisone and rituximab (R-CHOP), which was complicated by two episodes of febrile neutropenia. She responded well with complete remission of the bladder mass on cystoscopy 3 months after the completion of treatment. The bladder mucosa at this time had a polypoid appearance that was shown on biopsy to be oedematous and inflamed with no evidence of neoplasia. The patient remained well with no evidence of local or systemic disease. She is currently being maintained on third monthly rituximab, which will continue for at least 2 years.

Discussion

Primary non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the bladder (PNHLB) represents less than 1% of all bladder neoplasms and between 0.15% and 0.2% of all extra-nodal lymphomas [7]. This rarity is thought to reflect the absence of organized lymphoid tissue in the bladder wall [1,2]. There is female preponderance with a female to male ratio of 2.7:1 [4], and some authors suggest that this reflects an aetiological role of chronic inflammation; with chronic cystitis demonstrated in over 20% of patients [4–6]. Range of onset is 20–85 years with a median of 64–69 years [4,5].

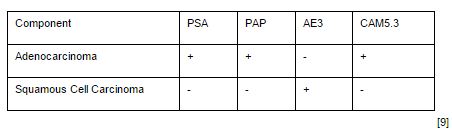

Most cases were published before 1999 and are described in terms of the older “working classification” for lymphoma, with immunohistochemistry performed in less than 20% of cases [8]. In a review of 100 cases; all but three were B-cell lymphomas, with 64% comprising low grade lymphoma [4]. Extra-nodal marginal zone/mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) type represent 52% of cases [1,4]. Primary Hodgkin lymphoma and T-cell lymphoma are exceedingly rare. Only 20–30% of reported cases represent high grade disease [4,5,8].

Haematuria is the most common presenting symptom (61%) followed by nocturia, dysuria and loin pain [4,8]. Intravenous urography reveals a filling defect in the bladder, while ultrasound displays a solid homogeneous mass [2]. CT scan exposes a contrast-enhancing soft tissue density either as a sessile solitary mass (66%), multiple sessile masses (14%) or as a polypoid mass [2]. Only one case was identified that described PET findings of PNHLB, in which a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma showed a clearly delineated hyper-metabolic mass [9]. Cystoscopy findings are most commonly of a solitary mass, followed by multiple masses and occasionally a diffuse lesion with nodule formation, with the lateral walls forming the most common site (40%) [1,2,5,8]. The lesion is usually rounded with overlying intact mucosa that may be oedematous, friable, haemorrhagic or ulcerated [3,10,11]. The definitive diagnosis must be histological [11,12].

The treatment of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma at other sites is heterogeneous and complex, and detailed discussion is beyond the scope of this article. It is essentially based upon histological classification, clinical stage and patient factors [13]. Bladder lymphoma is very treatable; with one review showing death from tumour in only three of 27 patients, and complete remission (CR) in the remaining 24 [5]. The most complete review of case reports found no difference in effectiveness between the three major treatment modalities (surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy) in low- or high-grade PNHLB [4]. For low-grade lymphoma; CR was achieved in 95% of patients treated with radiotherapy, 100% of those treated with surgery and 100% of those treated with chemotherapy [4]. For those with high-grade disease, CR was achieved in 72% overall, with systemic chemotherapy used in 60% of cases. CHOP and R-CHOP are the most widely employed chemotherapy regimens in the literature [4]. Two case reports describe complete remission of MALT type lymphoma with antibiotic therapy [4]. Rituximab alone may be effective in MALT lymphoma of the bladder as this has been successful in other sites [13,14]. Some authors recommend chemotherapy as the preferred treatment modality as it is less invasive than surgery or radiotherapy and has the theoretical benefit of treating undiagnosed areas of systemic spread [5,15]. This treatment regimen may not be well tolerated especially in elderly patients, and as such it must be made clear that there is no evidence to recommend any treatment over another, regardless of disease grade [15]. At other sites of extra-nodal lymphoma; less invasive treatments such as rituximab alone or localized radiation may be used as first-line therapy for low grade disease [13]. This may also be an appropriate strategy for bladder lymphoma, but at this stage there is insufficient evidence to make any recommendations.

Only four reports in English clearly describe primary follicular lymphoma of the bladder [3,5,15]. All four cases presented with haematuria. No cases describe the radiological findings. Three cases presented as solid masses and one as multiple sessile tumours. Radiotherapy with or without surgery successfully treated all four cases [3].

Conclusion

In summary, PNHLB is an exceedingly rare condition that is difficult to diagnose based on clinical or radiological findings and as such diagnosis must be histological. There is insufficient evidence to recommend a particular treatment over any other. As in the management of lymphoma elsewhere, treatment should be tailored to individual patient and disease factors.

We present what is, to our knowledge, the first case of follicular lymphoma of the bladder treated with chemotherapy, as well as the first published images of combined PET/CT of primary lymphoma of the bladder.

References

1. Taheri M, Dighe M, Kolokythas O, True L, Bush W. Multifaceted Genitourinary Lymphoma. Current Problems in Diagnostic Radiology. 2008;37(2):80-93.

2. Tasu JP, Geffroy D, Rocher L, Eschwege P, Strohl D, Benoit G, et al. Primary Malignant Lymphoma of the Urinary Bladder: report of three cases and review of the literature. European Radiology. 2000;10:1261-4.

3. Bhansali SK, Cameron KM. Primary Malignant Lymphoma of the Bladder. British Journal of Urology. 1960;32:440-54.

4. Hughes M, Morrison A, Jackson R. Primary bladder lymphoma: management and outcome of 12 patients with a review of the literature. Leukemia and Lymphoma. 2005;46(6):873-7.

5. Oshawa M, Aozasa K, Horiuchi K, Kanamaru A. Malignant Lymphoma of Bladder: Report of Three Cases and Review of the Literature. Cancer. 1993;72(6):1969-74.

6. Suzuki T, Matsumura T, Oto I. Intravesical Mass consisting of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. International Journal of Urology. 2004;11:1028-30.

7. Freeman C, Berg JW, Cutler SJ. Occurence and Prognosis of Extranodal Lymphomas. Cancer. 1972;29:252-60.

8. Fernandez Acenero MJ, Martin Rodilla C, Lopez Garcia-Asenjo J, Menchero C, Sanz Esponera J. Primary Malignant Lymphoma of the Bladder. Pathology, Research and Practice. 1996;192:160-3.

9. Mantzarides M, Papathanassiou D, Bonardel G, Soret M, Gontier E, Foehrenbach H. High-Grade Lymphoma of the Bladder Visualised on PET. Clinical Nuclear Medicine. 2005;30(7):478-80.

10. Downs TM, Kibel AS, DeWolf WC. Primary Lymphoma of the Bladder: A Unique Cystoscopic Appearence. Urology. 1997;49:276-8.

11. Davidson N. Primary Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma of the Bladder. Scandanvian Journal of Urology and Nephrology. 1990;24:155-56.

12. Yeoman LJ, Mason MD, Olliff JF. Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma of the Bladder: CT and MRI Appearences. Clinical Radiology. 1991;44(6):389-92.

13. Kobrinsky B, Hymes KB. Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. [Internet] London: BMJ Publishing Group; 2012 [updated February 20 2012; cited 5th October 2012]; Available from: Best Practice.

14. Shetty RK, Adams BH, Tun HW, Runyan BR, Menke DM, Broderick DF. Use of Rituximab for Periocular and Intraocular Mucosa-associated Lymphoid Tissue Lymphoma. Ocular Immunology and Inflammation. 2010;18(2):110-2.

15. Heany J, Delellis R, Rudders R. Non -Hodgkin Lymphoma arising in the Lower Urinary Tract. Urology. 1985;25(5):479-84.

Date added to bjui.org: 04/11/2013

DOI: 10.1002/BJUIw-2012-076-web