Surgical Science – everything is not what it seems

It has been another successful year for the BJUI. Our impact factor has gone up, the new design theme of ‘places’, featuring the location of the ‘Article of the Month’ on the front cover, has been well received and our web statistics have gone from strength to strength. Despite these successes, as a surgeon-scientist, I occasionally find that I am questioning myself, particularly where surgical science is concerned.

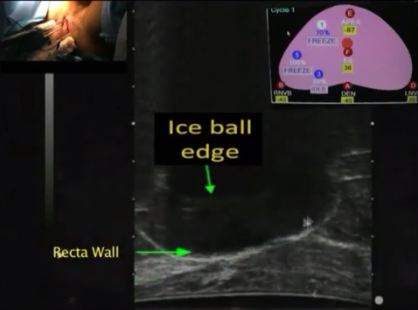

One such moment came recently while I was performing a live nerve-sparing robot-assisted radical cystectomy (RARC) during the European Association of Urology Robotic Urology Section (ERUS) 2014 meeting in Amsterdam. Open RC (ORC) is a morbid procedure and in cohort studies we thought that we had halved the complication rates with laparoscopy and lowered them even further with robotics. However, these results have not been replicated in randomised controlled trials. A letter in the NEJM comparing ORC and RARC showed no difference in outcomes, especially complication rates. Many feel that perhaps there was a difference in the experience of surgeons performing ORC and RARC, although the article itself mentions that this was not the case. Our own CORAL (randomised controlled trial of open, robotic and laparoscopic radical cystectomy) study comparing ORC, laparoscopic RC and RARC demonstrated no difference in 90-day complication rates, although all diversions were performed extracorporeally. In this issue of the BJUI, we present another randomised trial of ORC vs RARC showing no significant differences in health-related quality of life with scores returning to baseline after 3 months. We now await the results of the multicentre RAZOR (randomized open vs robotic cystectomy) study, which is expected to recruit fully this year. As I performed live, I could not help thinking about the negative results of these trials, which came up during my discussions with the audience. It is often good to question yourself rather than have blind faith without the scientific evidence.

Now for some positive news. It is becoming increasingly obvious that perhaps choline positron emission tomography (PET) will soon replace bone scans for detecting metastasis in prostate cancer. As tracer technology develops further, the death of traditional bone scanning in coming years seems imminent.

Finally, we have some exciting science for your reading pleasure. While the management of Peyronie’s disease has largely centred on various surgical techniques, there may be a new treatment for the plaque itself just over the horizon. The answer – ‘small hairpin RNA’; these can inhibit histone deacetylase 2 and induce plaque regression. Currently reported in a rat model, Phase I studies cannot be far away.

Prokar Dasgupta

King’s College London, Guy’s Hospital, London, UK