Editorial: PCa BCR after SRT – first look into risk stratification and prognosis

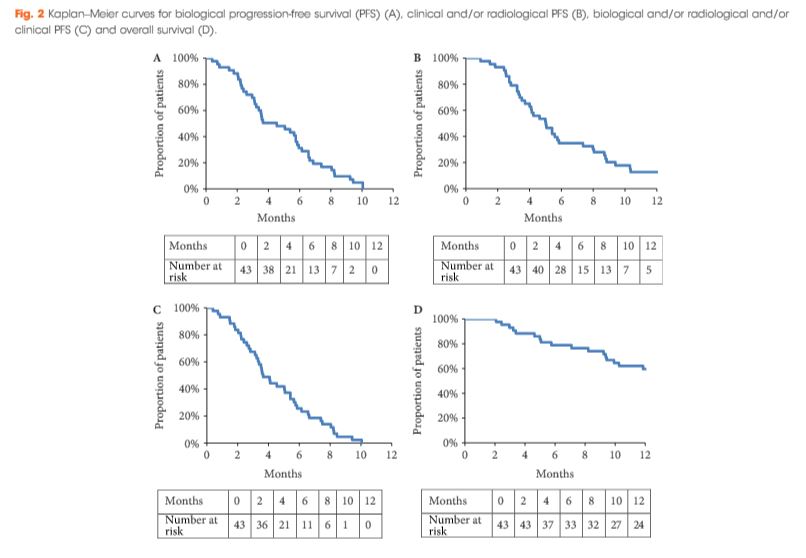

As salvage radiation therapy (SRT) is commonly offered as a treatment option to select patients with prostate cancer who have biochemical recurrence (BCR) after radical prostatectomy (RP), the uro-oncology community is in strong need of tangible data regarding patients who have a ‘second’ BCR after such therapy. The multi-institution team led by Tumati and Jackson [1] provides new insight into the outcomes of second biochemical failures, offering a novel risk stratification system with the help of prognostic factors. Their analysis of 286 patients offers retrospective prognostic clues that could guide further work trying to better understand the natural history and management of such patients.

At the core of their findings is two risk stratification grouping systems predicting event rates for freedom from distant metastases (FFDM) and for prostate cancer-specific survival (PCSS), both based on multivariate analysis. Variables such as interval from RP to second BCR, Gleason score, and concurrent androgen-deprivation therapy (ADT) proved to be of significance. Of note, their cohort also allowed them to establish an overall survival from time of second BCR diagnosis of 13 years, a surprisingly hopeful figure for such treatment-resistant disease.

Whilst the classification proposed by Tumati et al. [1] brings valuable numbers to this poorly understood patient group, some questions remain about parts of the analysis performed. First, it came as a surprise to our team that, on multivariate analysis, FFDM and PCSS did not significantly correlate with clinical staging or nodal involvement, two well-established predictors of poor outcomes after RP [2]. Although both risk factors either reached or approached statistical significance on univariate analysis, we have difficulty explaining why such clear prognosticators would not reach significance with other factors controlled. Maybe the lack of systematic, complete lymph node sampling could partially explain the lack of significant correlation with N staging. Also, whilst some may find it surprising that positive surgical margins were insignificantly associated with better long-term outcomes, other published studies have actually shown similar results, sometimes with statistical significance [3, 4]. This could have very important implications, as it suggests that treatment options for patients with positive margins might be applied more selectively, and that systematic SRT might not be necessary in most cases.

We also would like to question the risk grouping proposed in the article to predict FFDM after 6 years (6-year FFDM). By combining patients with no risk factors (6-year FFDM = 75.8%) to those with either Gleason score 8–10 (6-year FFDM = 54.3%) or concurrent ADT (6-year FFDM = 64.0%) in a single group, the favourable prognosis of patients without any risk factor seems inappropriately merged with the two poorer-outcome risk factors, leading to an overall 6-year FFDM of 71% in that group. Based on the tables presented, separating patients with no risk factors from those with a high Gleason score or with concurrent ADT to create a separate risk group seems essential to optimise stratification given the striking difference in FFDM rates. We are also wondering why a similar weighted-risk grouping was not performed for PCSS, given that hazard ratios for the same variables were similar between FFDM and PCSS.

Another important limitation, as acknowledged by the authors, lies in the lack of analysis based on the period of treatment over their 27-year review (1986–2013). Although they provide second BCR rates for every decade, they do not to perform complete subgroup analyses for separate periods. As discussed in the article, 2004 marked an important change in the technique of RT at their institutions (three-dimensional planning vs intensity-modulated RT) and could have been used as a threshold to stratify patients based on era, which would have removed this possible confounder. Other important factors, also mentioned by the authors (e.g. increase in CT sensitivity over the years, problems with older ADT records, new therapies for castration-resistant prostate cancer since 2010), may have significantly influenced outcomes in the sample. We understand that most of these subgroupings, even if theoretically necessary, would probably have made analyses underpowered. Furthermore, as discussed in the paper, it would have been relevant to study PSA doubling time, as it is a well-recognised surrogate for clinical progression and PCSS in primary BCR [5]; maybe similar results could have been expected in second BCR.

Overall, our team thinks that the study led by Tumati et al. [1] reached its primary objective of describing the natural history of second BCR following SRT after RP, whilst providing new, multi-centric data on this poorly explored topic. Moreover, the proposed risk stratification system for FFDM and PCSS after 6 years provides much needed prognostic insight for treatment-resistant disease. In addition, such data can help design future trials assessing new treatment options or novel diagnostic techniques and improve clinical management of second BCR.